By Soraya Ferdman

George Freeman is the Executive Director of the Media Law Resource Center (MLRC), a nonprofit trade association that supports the media in legal matters. Previously, he worked as the chief First Amendment lawyer in the legal department of the New York Times for 31 years, offering legal advice to staffers. Under Freeman’s tenure, The Times did not lose or settle a single libel case.

The MLRC issues annual reports on the results of libel, privacy, and related trials involving media organizations. Their database includes information from 650 trials that occurred between 1980 to 2017. According to MLRC, the average number of defamation lawsuits that have gone to trial per year is at an all time low: between four and five in recent years, compared to 27 in 1980.

However, MLRC data only reflects the number of defamation cases that go to trial—the data doesn’t include suits that are filed but are dismissed or settled out of court.

During 2019 alone, First Amendment Watch (FAW) reported on 18 defamation suits that were filed against media defendants, complicating any assumption that media companies have been freed from defamation threats (and FAW does not necessarily write about all such cases). A number of these cases involve internet speech, which has raised new legal questions such as whether a retweet is considered an endorsement, or whether statements made online are more likely to be interpreted as an opinion rather than a fact.

FAW staff writer Soraya Ferdman spoke to Freeman to get a better sense of today’s defamation landscape, and how the internet has impacted media litigation.

FAW: One of the cases that people thought was going to be really important was the defamation lawsuit filed against Joy Reid for retweeting a picture that was later proven to be mischaracterized. Does the ease with which people can retweet and thus republish false information raise the risk of defamation? Is this a new source of litigation that you expect to see more of?

Freeman: I’m reluctant to say that in general any increase in libel litigation is due to digital technologies. Frankly, I predicted that would be the case 20 years ago when websites and digital communications became more popular. If anything, at the time, we saw a decrease in litigation. That was quite stunning to me, because I would’ve thought that given the speed the digital world requires, there’d be less editing, more mistakes, and thus, more lawsuits. But, in fact, the opposite occurred: During the early 2000s, which I’d say, was the height of digital growth, there actually were less lawsuits.

I think the reason for that was that no one took digital communications seriously. In other words, your reputation wasn’t very much injured if you were slurred on a website or a blog as opposed to The New York Times. If you felt there was a mistake about you and you called in, the chances were that the article would be changed and it could be done in a matter of minutes as opposed to the print version where they write a retraction letter and it sits on someone’s desk, and then maybe a week later there’s a retraction that doesn’t really satisfy the person, or maybe there’s no retraction at all. But making a change in response to a complaint–if the response seems warranted–appears to be part of digital culture. For those reasons, I think we saw a decrease in lawsuits, not an increase because of new technology.

FAW: So, essentially despite people’s assumption that a faster news cycle would prompt more defamation suits, what you actually have is that it helps to more quickly clarify mistakes and thus prevents them from escalating into lawsuits?

Freeman: Yes. And, I think concomitantly, people don’t take what’s on a web blog seriously. And so, [blogs] are less important and viewed as having less credibility.

FAW: But that’s not always the case, right? Take Alex Jones’s defense in the Sandy Hook defamation suit. His lawyers argued that conspiracy theories were protected rhetorical hyperbole, and that people didn’t expect Jones to present real facts. Conspiracy theories are a great example of a case where most people understand the information they dispel to be a web of lies, while many others take them really seriously to the point where they may act on them.

“I’d be careful before attributing the increase in defamation suits now to the internet. I think the increase now it can be better attributed to the political environment and the President.”

Freeman: Well, legally the standards are the same whether it’s print or digital. I just think it’s going to be a hassle to file a lawsuit and dealing with all the consequences of that financially, psychologically, et cetera. [Because of this] I think it’s more likely that people will just let it go because it was on the web, as opposed to let it go because it was in The Washington Post. You know, when it’s in a newspaper and there’s more gravitas, it does more to impact your reputation.

FAW: I’m surprised. I walked into this conversation really thinking that the opposite was true, that the internet has resulted in more defamation cases, not fewer.

Freeman: Well, I’m saying I thought the opposite was true too. I expected there to be more cases on the internet, but if you really look when the internet became popular, which was really in the early 2000s, there seems to be, at least anecdotally, a decrease in the number of lawsuits. All of the practitioners, including myself, basically saw and agreed that there was a decrease at that time. And it was surprising because it was really the time when we expected to see an increase.

In other words, I’d be careful before attributing the increase in defamation suits now to the internet. I think the increase now can be better attributed to the political environment and the President.

FAW: When Trump was on the campaign trail, he said he would change libel laws so that it would be easier to sue people for defamation. People responded, saying that it wasn’t within his powers. Even if he can’t change libel laws, what effect has his anti-press rhetoric had on people’s willingness to defend journalists who are accused of libel?

Freeman: The libel laws haven’t changed, and he’s not going to change them, but he has created an environment where attacking the press has become commonplace, not only by him, but by many of his followers and supporters. He intentionally intends to demean and to lower the credibility of the press [because] it is one of the things that can stand in his way of doing what he wants to do.

The polls show a general lack of respect for the press, and that can lead to more lawsuits. [The rhetoric] has the potential, although we haven’t seen it yet, to lead to more plaintiffs’ verdicts and higher jury awards if jurors buy into this sort of stuff. I tried to get some evidence and some numbers on that, but there have been so few jury trials and there’s not enough evidence there to support that proposition.

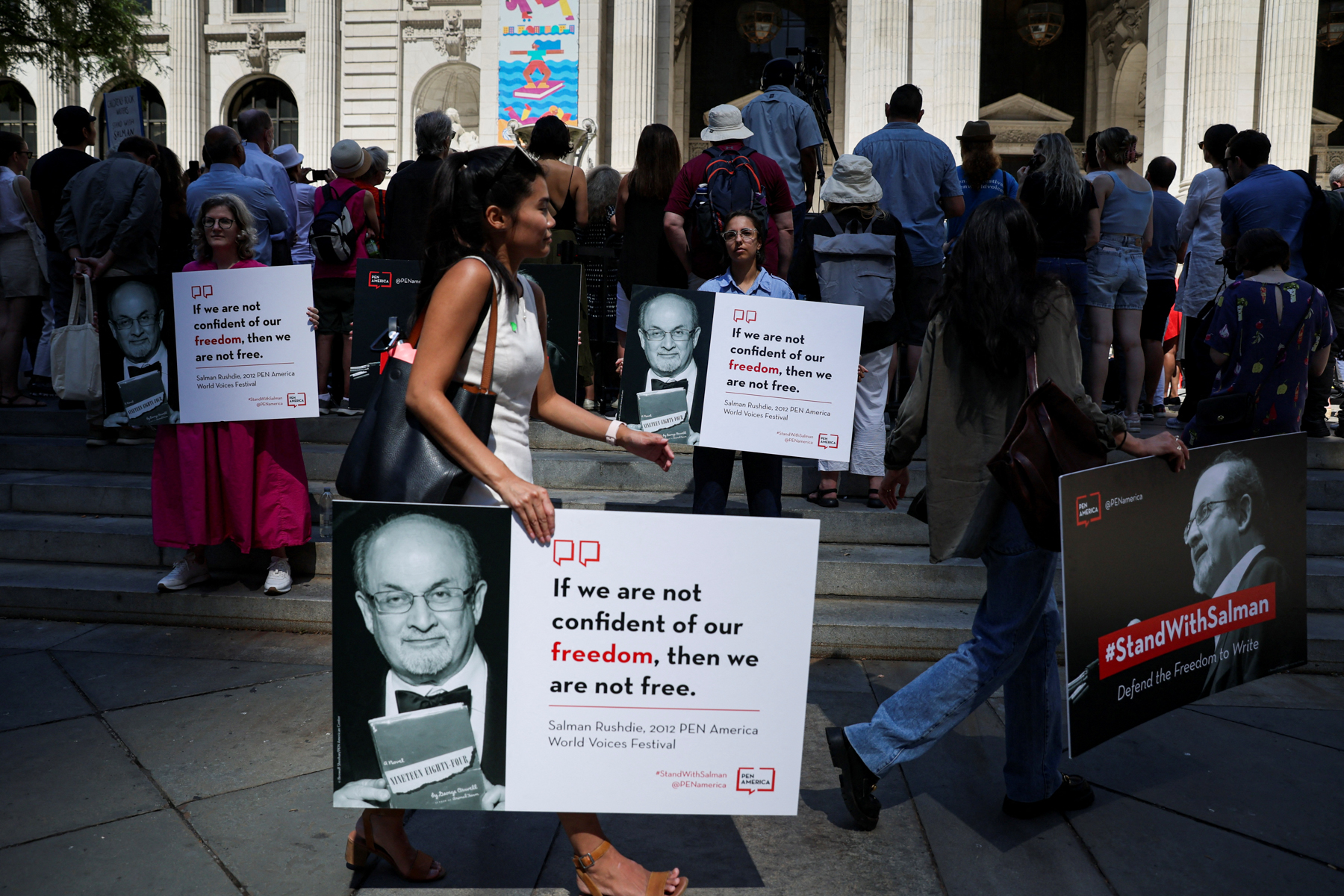

MSNBC correspondent Joy Reid checks her phone after a taping of Meet the Press. Reid was sued for defamation after retweeting a photo later proven to have been mischaracterized.

Phil Roeder / Wikimedia Commons

FAW: You were trying to get evidence on jurors’ opinion on the press? What were you expecting to find?

Freeman: We track jury verdicts and have numbers as to what percentage of jury cases are won by defendants as opposed to won by plaintiffs. And generally, the plaintiffs win two-thirds of the time, as I recall. I think the percentage came down a little over the last decade, and is now 50-50, but it’d be interesting to see whether those numbers have changed, and whether a jury is going to be more more pro-plaintiff because of the residual effects of Trump’s attacks. [1]

I have said many times that if I were trying a case tomorrow, the first thing I would do is tell a judge that the words “fake news” can never be mentioned during the trial. It’s a meaningless but prejudicial term, and you don’t want to color the jury’s mind. My guess is that most judges would grant that motion because it is prejudicial, and because it probably has nothing to do with a particular libel case you might be trying. The term could really affect the jury just as it has affected the culture in general.

FAW: If we think of the anti-media rhetoric as a kind of war over who gets to decide the norms of public discourse, then defamation suits become a tool for politicians to challenge negative reporting. I’m thinking of Devin Nunes’s suits against Twitter and Hearst Magazines, which seems to be a kind of political tool. I can imagine they were always used by politicians as political tools against their critics, and we have high defamation standards to protect the press, but it seems like it’s a strategy that is gaining in popularity. [2]

Freeman: You’re right. I think part of what you just described is simply the polarization, not only in society, but in the media. Where basically, the liberals are going to sue Fox news, whether it’s a meritorious suit or not. And likewise, conservatives are going to sue MSNBC, etc.

But, the Nunes suit is a good example. I can’t imagine that any lawyer would say that’s a winning lawsuit. It seems like that has to be there for other reasons.

FAW: This goes back a little to something that you said earlier, that news sites can now correct information more easily than they could in the print era. But in other ways, the internet has meant that if someone says something bad about you and you didn’t think to correct it, the information could be attached to your name in a Google search. I think that changes the landscape for reputational harm.

Freeman: That’s a very good point. And that’s true. Though, that’s less in the way of libel and more in cases where someone did something really stupid when they were young and got arrested. If an article about your arrest becomes the first Google item in a search of your name, and that stays with you forever, it becomes hard to get a job. That’s a real problem.

Alex Jones of Infowars walks through the halls of the U.S. Senate’s Dirksen Senate office building in Washington, D.C. September 5, 2018. After spreading false information about the mass shooting in Sandy Hook Elementary School, Alex Jones was sued by multiple families whose children were killed during the shooting. REUTERS/Jim Bourg

FAW: Twitter often involves angry exchanges between people of different political views. I’m thinking of, for example, the recent Elon Musk’s case. This can include defamatory comments that people can later dismiss as hyperbole. Will the defense of rhetorical hyperbole and opinion consistently rescue people’s comments on Twitter from defamation suits?[3]

Freeman: I think the interesting question is: because of some of the features of the web, and because of the way people read on the internet, whether there will be a greater kind of permissiveness that statements are opinion when they’re said online. Even if that same language, perhaps, would not be viewed as opinion if it was in The Washington Post. And you know, we haven’t really seen enough to be able to say that that’s the case, but I think we’re leading in that direction. So on the one hand, you’re right that there’s a lot more biting, vituperative language out there, some of which may be defamatory, even though most of it is opinion and hyperbole. But my guess is that it will be somewhat counteracted by the courts being more permissive with respect to the language on the internet, under the view that people don’t take it as fact.

[1] According to the MLRC 2018 Report on Trials and Damages, media defendants won 37.3 percent in 1980-1989, 40.4 percent in 1990-1999, 52.1 percent in 2000-2009, 42.2 percent 2010-2017.

[2] In addition to data on jury decisions, the MLRC 2018 Report on Trials and Damages shows that post trial settlements are on the rise. The share of trials eventually settled was 7.5 percent in the 1980s, 17.7 percent in the 1990s, 18.5 percent in the 2000s, and 31.9 percent in the 2010s.

Tags