Update 8/3/21: Congressman Devin Nunes (R-CA) filed a libel suit against NBCUniversal and MSNBC host Rachel Maddow over comments she made in March about his relationship with a Ukrainian lawmaker and suspected Russian spy.

Update 11/18/20: Representative Devin Nunes (R-CA) filed his eighth defamation suit in under two years, this time against The Washington Post and reporter Ellen Nakashima for defamation.

By David L. Hudson, Jr.

In February 2016, presidential candidate Donald J. Trump vowed to “open up” libel laws, a position he maintained after he assumed office. According to Trump, the law as it stood made it too difficult for a public official like himself to protect his reputation. “Our current libel laws are a sham and a disgrace and do not represent American values or American fairness,” Trump said in 2018, and again promised to do away with legal protections that have existed for more than 50 years.

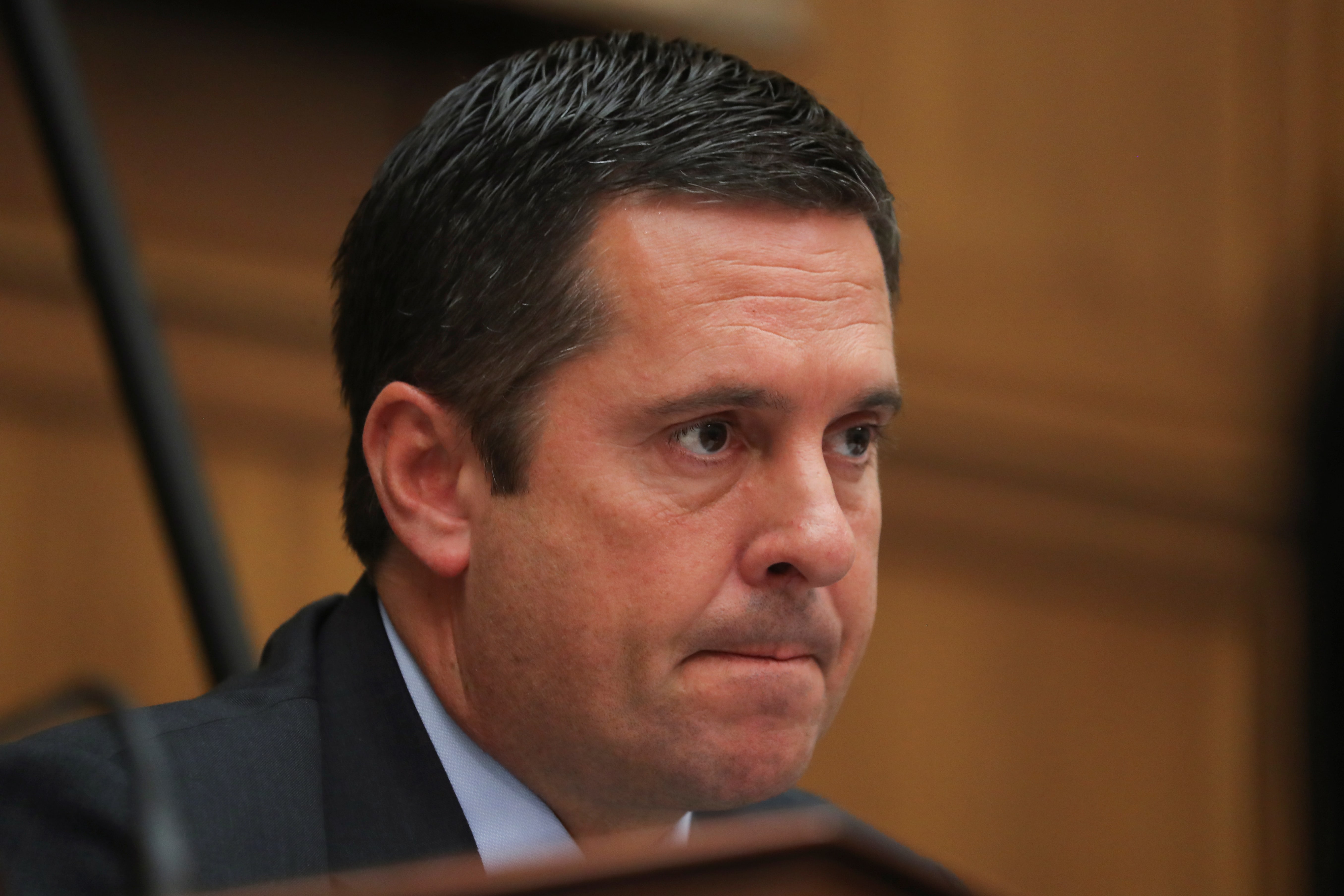

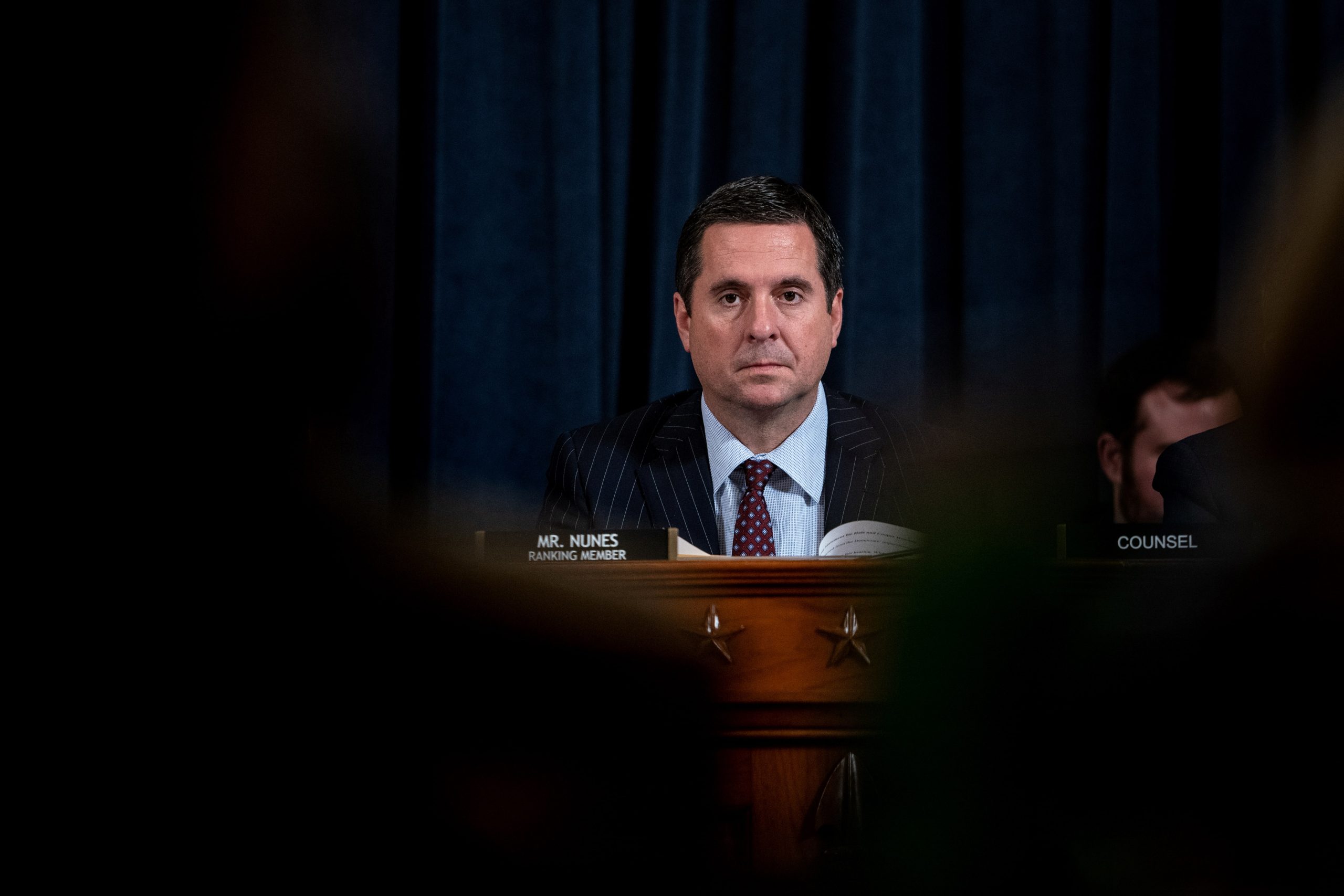

Unsurprisingly, Trump has not been successful in changing defamation standards, a power that traditionally rests in the hands of the judicial branch. Still, that hasn’t stopped him and his political ally, Rep. Devin Nunes (CA) from using libel lawsuits as a weapon to fight back against what they perceive as unfair criticism.

In February 2020, the Trump campaign filed a defamation suit against The New York Times over an editorial piece that claimed the campaign colluded with Russian to defeat Hilary Clinton. Soon after, the Trump campaign filed a defamation suit against The Washington Post for two essays that said the Trump campaign accepted interference from foreign governments in the 2016 Presidential election. And then, in the third defamation suit filed within a ten-day period, the campaign sued CNN – long a subject of Trump’s wrath – for a June 2019 editorial arguing that then-FBI director Robert Mueller should have charged Trump with obstruction of justice.

Notably, the President has not limited his targets to large media companies. In April 2020, Trump’s re-election campaign filed a libel suit against a local TV station in Wisconsin for running a liberal advertisement. With fewer financial and legal resources at their disposal, local media organizations are more likely than their larger counterparts to censor their reporting in order to avoid retribution from the President.

Under the U.S. Supreme Court’s celebrated decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), public officials, such as Trump, face a difficult challenge in order to win a winning libel suit. They must prove by clear and convincing evidence that a defendant published a defamatory falsehood with a high level of “fault”—knowing that a statement was false or acting in reckless disregard as to the truth or falsity of the statement. Even though Trump’s lawsuits against the national media groups are unlikely to win in court, they may still manage to intimidate smaller publications from publishing criticism of his administration.

Trump’s barrage of libel lawsuits, however, is nothing compared to one of his chief defenders in Congress, Nunes, who has filed seven defamation suits in just the last twelve months. (One suit has been dismissed by a judge, and another suit was dropped.)

In March 2019, Nunes filed a $250 million defamation suit against Twitter and three Twitter accounts, including one belonging to GOP strategist Elizabeth A. Mair. Two of the accounts were clearly parodies: @DevinNunes’ Mom and @DevinNunes’ Cow. Nunes’s suit cited several tweets by the users who he says are “three bad actors,” and who “engaged in a joint effort” to defame him and interfere with his duties as a congressman.

The complaint also alleged that Twitter is an information content provider, and as such, is responsible for the content of the tweets published on its platform. Twitter “knowingly hosting and monetizing content that is clearly abusive, hateful, and defamatory” to undermine the public’s confidence in Nunes, the complaint read.

Clearly, the lawsuit against Twitter is blocked by Section 230, a federal law that generally insulates social media entities for posts by third parties. The judge presiding over his case thought so too, and dismissed Nunes’ claim on June 25, 2020, writing that current law prevents the court from treating Twitter as a publisher or speaker of third party content.

But Nunes’ $250 million lawsuit against Twitter is not even his biggest target. In December 2019, Nunes filed a $435 million defamation lawsuit against CNN, alleging that the network filed “a demonstrably false hit piece” over an alleged trip that Nunes took to Austria to meet an ex-Ukrainian official—a trip that Nunes said never took place.

As with Trump’s lawsuits, few if any of the Nunes’ are likely to win. But as some pundits have noted, that may not be their main goal. In addition to intimidating their critics, these lawsuits help push the narrative that media organizations regularly publish “fake news”.

Public officials using libel suits as a weapon against the press is nothing new. In the time of Times v. Sullivan, some Southern politicians resorted to libel suits to chill coverage of civil rights abuses. As Anthony Lewis explains in his book, “Make No Law: The Sullivan Case and the First Amendment,” the decision freed up the press and saved the Civil Rights Movement. Lewis writes in his book that at the time the Supreme Court decided Sullivan, southern officials had brought nearly $300 million in libel actions against the press. (For reference, Nunes alone has brought just over $900 million in defamation claims against his critics).

Many of the Trump and Nunes lawsuits will likely not meet the high standards required for public officials suing for defamation. Some may even be described as what George Pring and Penelope Cannan famously dubbed “Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation” or SLAPP suits. Such suits are filed more to silence opponents, rather than to vindicate actual reputational harm. Many states have passed so-called anti-SLAPP laws designed to provide defamation victims with the ability to file a special motion to dismiss and avoid prolonged litigation. However, there currently is no federal anti-SLAPP law, and some federal courts refuse to apply state anti-SLAPP laws in federal court.

Trump and Nunes are not alone in arguing that the Supreme Court gave too much protection to the press and made it too difficult for public officials to sue for libel. There is another public figure who has criticized the decision – Justice Clarence Thomas, who has himself endured unflattering press coverage, particularly during his contentious confirmation hearings in 1992. In a concurring opinion from a denial of certiorari, Thomas in McKee v. Cosby wrote: “New York Times and the Court’s decisions extending it were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law.”

Thomas’ view has little support among First Amendment scholars or, it seems, among his colleagues on the Court. Sullivan is arguably the most celebrated and important opinion in all of First Amendment jurisprudence because of the safeguard it provides for political speech.

The essence of the First Amendment is protection for criticism of government and public officials. In a republican form of government, in which the people elect their representatives, they must have the freedom to criticize the government without fear of punishment. As James Madison said, the First Amendment protects the “right of freely examining public characters and measures.”

Times v. Sullivan also articulated the central meaning of the First Amendment– “the profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”

Tags