WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is the first publisher in history to be charged with the World War I-era Espionage Act, and on Monday a London court ruled he can appeal against extradition to the United States, a key win in his nearly 15-year-long legal battle.

WikiLeaks, a website known for its publishing of classified information received from anonymous sources, published a trove of national security information leaked to Assange by U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning in 2010. The release revealed serious abuses by the U.S. military during the war in Afghanistan, notably including a U.S. military helicopter video which showed the killing of Iraqi civilians and Reuters journalists.

The U.S. Department of Justice filed an 18-count indictment in June 2020 against Assange for his role in the publication of the classified information. The indictment includes 17 charges under the Espionage Act of 1917, as well as one charge of conspiracy to commit computer intrusion under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which could complicate his First Amendment defense.

Assange has been held in limbo since 2019, detained in the high-security Belmarsh Prison in London, fighting the requests for his extradition to the U.S. If extradited, he could face up to 175 years in prison.

Monday’s ruling followed arguments from Assange’s lawyers that claim recent U.S. assurances that Assange would receive the same free speech protections as an American citizen if extradited were “blatantly inadequate.” High Court judges Victoria Sharp and Jeremy Johnson agreed, finding the assurances insufficient. The short ruling grants Assange permission to a full appeal of his extradition based on remaining questions of his First Amendment rights in the U.S. as an Australian citizen.

In an interview with First Amendment Watch, Rebecca Vincent, director of International Campaigns for Reporters Without Borders, discussed the complicated history of the Assange case, the far-reaching press freedom implications of his detainment, and the international fight for the end of his prosecution.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

FAW: What is your role in the campaign for Julian Assange’s release?

RV: I’m the campaigns director for Reporters Without Borders, also known as RSF, or Reporters sans frontières, and we have our own campaign to free Assange as part of our press freedom mandate. Our interest in the case is that we believe Julian Assange has been targeted for his contributions to journalism, because the publication by WikiLeaks of the leaked classified documents informed extensive public interest reporting around the world. And this information was in the public interest. It exposed war crimes and human rights abuses. We’re quite concerned as well that the way the U.S. government is pursuing this case, in particular charging him under the Espionage Act, will set a very dangerous precedent for journalism. He’s the first publisher that has actually been pursued under this law, and it has no public interest defense. So if this precedent is set, basically any media organization, any journalists around the world who works with stories based on leaked classified information could find themselves in the same situation. So our interest is in what he did, the reasons he’s being targeted, and then the implications it will set. And through our own campaign, I’ve become involved in many ways. Actually, I’m the only NGO observer who has attended all four years of extradition proceedings in U.K. courts, because I’m London-based. It hasn’t been easy because, frankly, the U.K. courts kind of lack a mechanism to really deal with NGOs. So they don’t quite know what to do with requests for observation that don’t come from the media. So we’ve had a bit of a fight. I’ve had to really fight my way in at some points. So I’ve monitored the legal proceedings, and I’ve been visiting him in prison. It was also a bit of a fight to get access, but I’ve been in five times since August. So I’ve got sort of rare access to him.

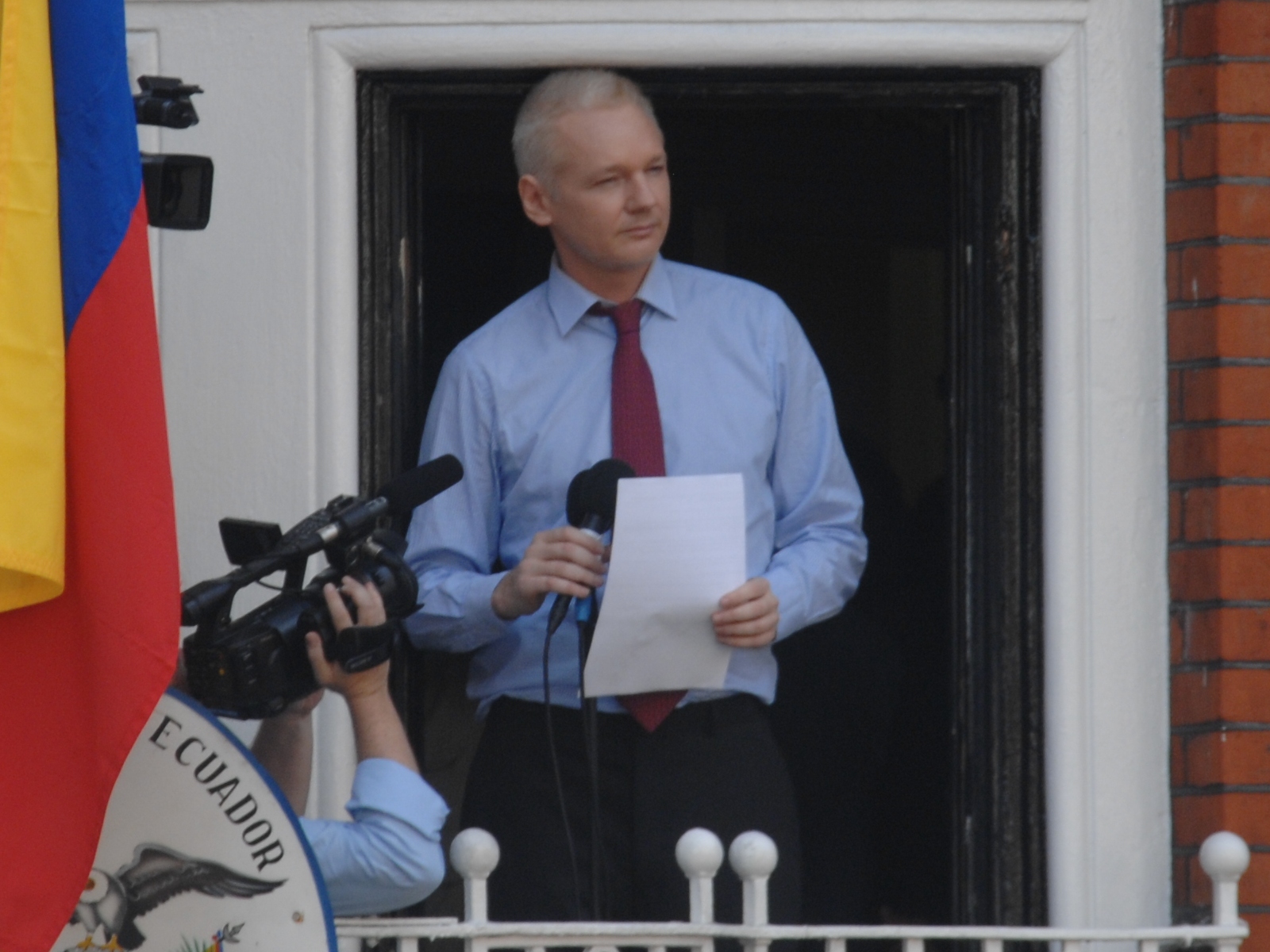

In this Reuters file photo, WikiLeaks’ founder Julian Assange leaves Westminster Magistrates Court in London Jan. 13, 2020. (Reuters/Henry Nicholls)

FAW: Can you speak about his state of mind and his feelings during the recent proceedings?

RV: So I’m not able to give too much detail about our discussions, just because we’ve had to go in as social visitors so it’s treated differently than a media visit, and I’m not a journalist anyway, I’m a campaigner. So we’re not even allowed to take anything with us, so much as a piece of paper. But what I will say is, we talk to him about our work on his case. He is very much still fighting for his own release. He is very involved in his legal case. And from our perspective, the advocacy that we’re doing, he has a right to know what’s being done on his behalf and it’s important that he’s able to speak with groups like ours. We have really serious concerns about his mental health and his physical health. It’s of concern in any situation of prolonged detention, which he’s in in the U.K. I think a lot of Americans have lost sight of what the status of this case is or what’s happened to him, but he’s been in a high security prison here for more than five years. And he’s been deprived of his liberty in different ways for more than 13 years, in fact, and so that’s taken its toll. When I visited him in January, he had been coughing so much from a respiratory illness that he had actually broken a rib and was in clear pain. And so there’s moments like this that are just a reminder of the grim conditions that he’s currently in. And of course, what has been discussed in court is how much worse it will be for him in a situation of extradition and if he’s held in conditions that we expect him to be held in of extreme isolation in a U.S. supermax facility, it will be far, far worse. So I know that there’s more focus on that, but the situation he’s in now is really also very worrying.

FAW: What do you expect from Assange’s case moving forward? What have the judges been particularly focused on?

RV: This has been such a long and complicated process. It’s always really important to understand the details of what’s coming up at each hearing. I think more publicly, there’s this sense that it’s never ending and for sure this has been going on for a long time. Where we’re at now is very specific. So there was a whole set of proceedings before, which started in February 2020. And eventually there was a decision on the first instance proceedings in January 2021 that was in his favor. In fact, that judge ruled that he should not be extradited, but only on mental health grounds. So we had criticized the decision at the time. Obviously, we welcomed the barring of extradition, but the substance of the decision was concerning, because it was not strong on the press freedom grounds, on free expression grounds, on human rights grounds that groups like us are concerned about. In fact, she largely found in favor of the U.S. arguments on those points. So everything that kind of followed that was then more narrowly focused on his mental health situation, and then the conditions he would likely be held at in the U.S. if extradited.

The U.S. then came forward with some diplomatic assurances, and I believe these were presented to the court in summer 2021, which actually was enough for then the Court of Appeal to overturn that decision that had barred extradition. So the U.S. made some promises. They said that he would not be held under special administrative measures, SAMs, and that he would not be held at the specific facility that had been discussed in court, and also stated a third point that he could be permitted to serve part or all of his prison sentence in Australia rather than in the U.S. That was enough for the judge at that stage to overturn the decision and then the Supreme Court neglected to further review it. So that was the end of that. All of that was then followed by the U.K. home secretary eventually signing an extradition order. So that happened in summer 2022.

In this April 11, 2019, file photo, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange arrives at the Westminster Magistrates Court, after he was arrested in London. (Reuters/Hannah McKay)

Julian was then able to appeal the extradition order itself. Eventually what came out was just a written decision of only three pages by a single judge rejecting all of Assange’s grounds for appeal without much explanation, I have to say it was very brief. Then, his defense was given the opportunity for one final appeal against that and so that’s where we are now. They brought forward nine new grounds for appeal. And that was considered in February.

So in February, this was the hearing that was being referred to as ‘Day X’ because there was a sense of possible finality. This hearing was two days, and the judges began to consider these nine grounds, and then in March issued a decision. It was a bit of an unusual decision. They issued a written decision allowing three of those nine grounds. They gave permission for those to go forward, but not in a kind of unfettered way. This is the unusual part. They baked into the court decision an invitation for the U.S. to provide assurances on these three points. So of course, at any point, the U.S. could have presented assurances, but it is unusual for a court judgment to actually formally invite that. So we’ve highlighted that quite a lot because these assurances are essentially only political promises between the U.S. and U.K. and they’re not enforceable. There’s no guarantee that any of them, whether from the last round, or from this round, would be respected in practice, because it’s just a matter of diplomacy, not of legality. So the U.S. judicial system does not have to abide by these once he’s there. They can kind of proceed how they want. And it’s very odd also for a case of such tremendous importance, historically and for the public interest to be decided on the matter of these political promises rather than legalities. So we’ve pointed to it, really highlighting the political nature of the case against Assange. But that’s what this decision did. So of the nine grounds, three were then allowed to go further. And those six that are closed now can no longer be further appealed in the U.K. So all that’s left is these three grounds. The U.S. did then, on the deadline that was specified, presented some assurances on these points … And if you look at the text of the assurances themselves … I personally think that the assurances are rather weak. So these are all questions related to whether he could be subjected to the death penalty once he’s in the U.S. because there is a concern that he could be accused of additional charges that could make him liable for the death penalty. And then another point being whether he would be given First Amendment protections as a foreign national, and the prosecutor has previously stated that he wouldn’t. So that’s an odd point to try to explain away with diplomatic assurances which cannot be trusted. Amnesty International has said these assurances “are not worth the paper they’re written on,” which is really accurate, actually.

FAW: Do you think the U.S. press protection guidelines should apply to Assange? Why or why not?

RV: The First Amendment should apply to everyone, right? And this is one of the concerning aspects that he may not be given First Amendment protections at all. Sometimes the question of whether he is or isn’t a journalist can be very divisive, and sometimes it can become a bit of a straw man in fact, because there’s almost this perception that if you don’t formally consider him to be a journalist, then you don’t oppose sort of the case against him or support him. And I’ve tried to find, as a campaigner, to work more to establish a common ground like whether or not somebody is formally comfortable applying that label to him, we should all be concerned about this case. Anybody who cares about journalism or press freedom, should see the motive of this case and sort of the implications it has. So unfortunately, I think, in a way, that the nuance of that won’t matter if the First Amendment doesn’t apply to him at all. In fact, the indications that we have, given the comments by the prosecutor before, that he would not be afforded First Amendment protections, that’s alarming. But also I want to point to the Espionage Act, because this is really concerning, I think, as well. This is coming at a time where there’s been widespread calls for reform of the Espionage Act, even not related to this case. There’s many reasons. This is an antiquated law. It was never intended to be used in this way. It was not supposed to be used against journalists and publishers or whistleblowers, and we have seen it used against a number of whistleblowers. Now, this is the first time a publisher is being pursued in this way. But this is an indication that the law, which was developed in a very different world for very different purposes, could be used in this way. The fact that it has no public interest defense means, as well, that nobody accused in this way can have a fair trial because Assange and anybody else who would find themselves in a similar position cannot defend the basis of their actions as having been in the public interest. So there’s these two questions that mean to me inherently, you can’t get a fair trial: the First Amendment protections and the nature of the Espionage Act lacking a public interest defense. So I think that’s really important for Americans to understand. And this case becomes further complicated by the fact that of course, he’s not American. And so the U.S. going after somebody that is not a citizen, that has no ties to the U.S. He’s an Australian national, he was living and working in London at the time of these publications and at the time that the case was opened against him. That’s really concerning internationally, in this global rules-based system that a state could go after another person in this way. That means that if this goes forward, if the U.S. government succeeds in securing his extradition and prosecuting him there, this will have a chilling effect on global media freedom, not just media freedom in the U.S.

FAW: What does the prosecution of Assange, in your opinion, mean for other journalists? The future of journalism?

RV: Sometimes I use the language that it is about the future of journalism, and that the implications can’t be overstated, and I stand behind that. I think we will have already seen a chilling effect over these years, very few people would be willing to put themselves in the situation that he’s [Assange] been in for 13 years already, but the persecution and prosecution has meant he’s been deprived of his liberty in various means. The United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention does consider his period at the Ecuadorian embassy in London to have been arbitrary detention. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture found that he had suffered psychological torture during that time and now we know the state of his physical and mental health. Very few people would willingly put themselves in that situation. I think this treatment of him during this time has already had a chilling effect. We won’t know what stories have not been told as a result of this. But if it goes forward, that will be so much more severe and pronounced everywhere. It is criminalizing something that is actually part and parcel of journalism. And if they start with Julian Assange, it could easily be applied to, for example, outlets that published stories based on the leaks, including publications like The New York Times. I mean, this is a problem not just for WikiLeaks and for Julian Assange, but for the mainstream media. And I think that’s not widely enough understood either. He’s portrayed as being many things, there’s many levels of misperceptions about the case. I found as a campaigner, many people believe things about him that are not true or about the case that are not true. And that’s very difficult for us to correct because in many of the cases we work, we’re trying to inform and mobilize the public but most people after all these years have a view of this case, they think they know what it’s about. And that’s much harder to correct and to change people’s minds than to simply inform somebody of something that they weren’t aware of in the first place. So there’s a lot of dangerous implications here. And I think it’s really time for more solidarity. We’re seeing solidarity from the global media. We see some of it in the U.S. as well, but I think there’s a need for more in particular in the American media context to understand that this will impact them too.

Supporters of WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange block a street during a protest outside the Royal Courts of Justice in London, Britain, Oct. 28, 2021. (Reuters/Henry Nicholls)

FAW: President Biden recently said that he would “consider” Australia’s request to drop the prosecution. What was your reaction to that?

RV: I seriously hope that the Biden administration is considering this. This has been our main advocacy call all along. So of course, we’re engaging with the legal proceedings in the U.K. And there’s still a chance that there could be a legal solution here, either still at the U.K. level with this narrow chance left here or at the Court of Human Rights. But ultimately, this is a political case and it may require a political solution. And it is still in the power of this administration to bring it to a close at any time. And so we’ve been calling for exactly that: drop the charges, close the case and free Assange. Whether or not the president had deeply considered it in the moment that he responded to this question. I saw the video. It was a very quick response. I hope it does indicate that. It’s impossible to know the full context of that. But it does come against the backdrop where we know there have been diplomatic discussions between Australia and the U.S. We’ve been encouraged by the position of this administration in Australia, which has been advocating for him as an Australian citizen, in sort of contrast to previous administrations that were not as strong on the case. But I really want to emphasize one point here, too, that it’s not just about bringing it to a close. We are calling for a solution that involves no further time in prison for Julian Assange in the U.K. and the U.S. and Australia, anywhere. We don’t believe he should be in prison at all. So some of the language that’s used by officials around that has not gone that far. And I think that’s an important point. It’s not just about preventing extradition. Or, you know, bringing it somehow legally to a close, but ensuring that he cannot be imprisoned one day longer on these grounds because the publication of these materials was in the public interest.

We don’t quite know what happens next. So if it comes to a close, what should happen is that his right to appeal to the European Court should be respected. There’s a little concern about the political environment with the U.K. and this is an important point that we sincerely hope that the U.K. respects the European Convention obligations and does not move to extradite him while consideration of his appeal is ongoing there. But there’s some concern, including those very close to Assange on that point, so it’s worth looking at what happens next, but what should happen is that an appeal is allowed to Strasbourg so this could take some time actually to fully resolve here.

More on First Amendment Watch: