Gene Policinski, president and chief operating officer of the Freedom Forum Institute

The Newseum Institute’s First Amendment expert, Gene Policinski, originally published this commentary on April 18, 2019, on the Newseum blog, and has given First Amendment Watch permission to reprint.

For the latest news on the indictment of Julian Assange, click on the box below.

FAW News Coverage of Assange’s Indictment

For an in depth examination of WikiLeaks’ history and legal cases, click on the box below.

First Amendment advocates may well be stuck sometime down the road with Julian Assange’s WikiLeaks defense — even if it sticks in some throats.

Assange currently faces extradition to the U.S. for prosecution on computer hacking charges related to WikiLeaks obtaining and posting classified military data, memos and such in 2010 from then-U.S. Army soldier Chelsea Manning. The specific charge sidesteps for now a collision with the First Amendment, which does not protect anyone from prosecution for criminal acts, such as breaking into government computers.

But as the Assange saga unfolds, a number of news outlets report that U.S. prosecutors may bring additional charges ranging from how Assange dealt with his sources to the dissemination — Assange would say “publishing” — of that stolen material. That’s where it will get sticky for journalists.

Those added charges likely would threaten legal protections afforded to those who report confidential information obtained by others. One, known informally as the “over the transom” or “innocent third party” defense, protects those receiving and reporting information who are not involved in the act of obtaining it. A transom is a small window above a door that can be tilted open while the door below remains shut — hence, information dropped into a room “over the transom,” shields the party delivering it.

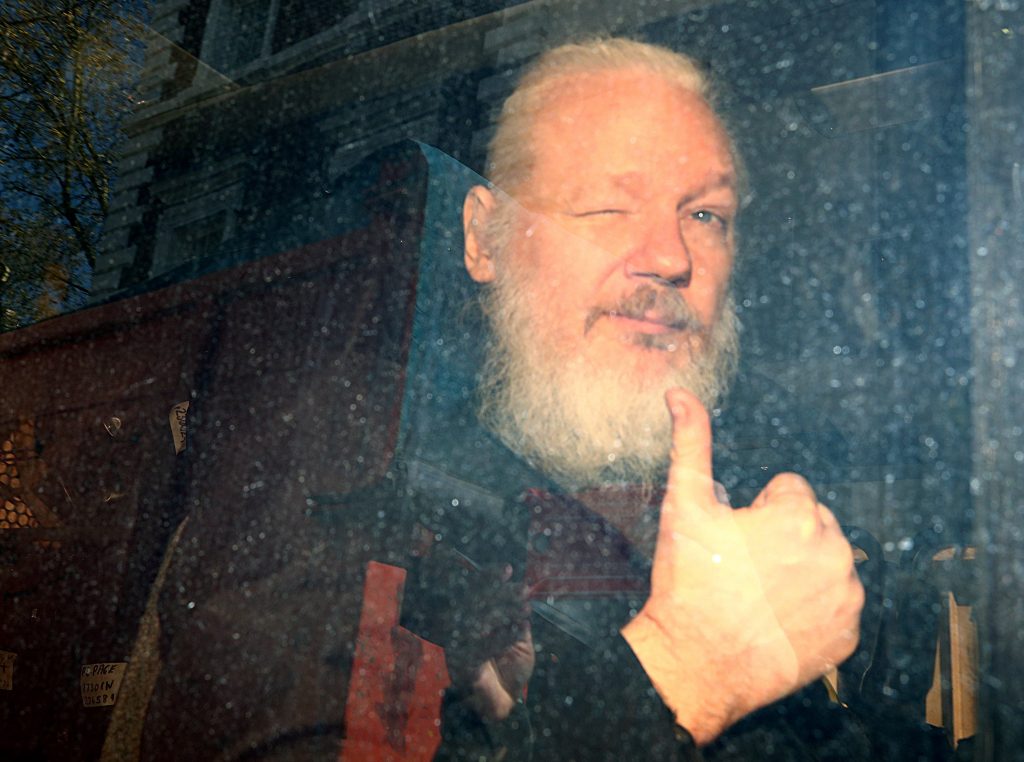

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange arrives at the Westminster Magistrates Court, after he was arrested in London, Britain April 11, 2019. REUTERS/Hannah McKay/File Photo

A 2001 Supreme Court decision in Bartnicki v. Vopper involved illegally intercepted telephone conversations. The 6-3 decision said that while the government certainly could charge persons who intercepted the calls, it could not successfully prosecute the radio host who was given a recording and played portions of those conversations over the air. The court noted the privacy aspects of the case gave way to reporting on matters of high public interest.

In the years since, journalists have relied on that ruling in reporting national security secrets and confidential city records. In turn, authorities have for various reasons focused on prosecuting the “leakers” rather than those who published the information. However, Bartnicki has not been directly tested in a national security setting — it was a civil lawsuit, not a criminal case.

At least one Justice Department prosecution came close to charging a journalist who received classified information. In 2013, Fox News reporter James Rosen was declared an unindicted co-conspirator under the Espionage Act during an investigation of a State Department employee who leaked information to him involving North Korean missile tests. The official was convicted under the Espionage Act, but Rosen was never prosecuted.

Assange, an Australian computer programmer and social activist at an early age, now loudly proclaims himself a journalist and that WikiLeaks is a news organization. But leading First Amendment lawyer Floyd Abrams has written a well-founded repudiation — WikiLeaks does no real reporting, adds no analysis or context and seemingly fails to consider the harm its “data dumps” of state secrets may cause others.

Others raise a pragmatic point — Assange’s release of state secrets has proven to be a major factor in discouraging Congress from enacting a proposed federal “shield law” that would (with no small amount of irony here) largely protect journalists from federal courts and grand juries demanding to know confidential sources.

But the American Civil Liberties Union, Committee to Protect Journalists and Assange’s lawyer Jennifer Robinson all said extraditing and prosecuting Assange sets a dangerous precedent for U.S. journalists who could to face similar charges brought by repressive foreign governments for publishing truthful information.

Some journalists and activists see a lack of support among U.S. editors and reporters as something more sinister, some writing that failing to back Assange exposes those journalists as unwilling to challenge government propaganda or power, even being “tools of the Empire.”

I’m for parsing things this way — consider Assange a political player who actively encourages information leaks and uses a journalist’s tools to influence political policy disputes, debates and decisions. Let him argue “free speech” rather than “free press.” There is an argument that even under the Espionage Act there is a defense of sorts — intent was in the public interest rather than in bringing harm to the United States. Chalk the unwillingness of many journalists in the U.S. to back Assange to something more pragmatic than philosophical. A friend and longtime journalist put it this way: “It’s how cops view someone who puts on a stolen uniform and badge.”

The U.S. government’s prosecution ultimately may rest on showing how — and to what degree — Assange cultivated Manning as a source. If he is found to have conspired with Manning on the theft, there’s no First Amendment or Bartnicki defense. Even there, though, the impact on journalists is concerning — the public is not served by restricting national security reporters to sitting in offices waiting for materials to land in their collective laps.

Any additional charges brought against Assange should be considered in the context that it is in the public interest that reporters be able to reach out to experts working on national security matters to discuss policy and even have conversations about how information might influence public views if disclosed.

Yes, that may well mean drawing a fine legal line between “cultivating” sources and conspiring with them. But we have all been well-served by disclosures in the public interest of secret or confidential government documents and information — from the Pentagon Papers to undisclosed telephone and internet surveillance programs to information that properly armored vehicles were not reaching U.S. troops overseas, causing unnecessary deaths.

Journalists are the watchdogs by which we all can know information improperly classified, withheld for political gain or around which legitimate debate should occur — a process that could also be described to operate in the interest of national security.

Gene Policinski is president and chief operating officer of the Freedom Forum Institute. He can be reached at gpolicinski@freedomforum.org, or follow him on Twitter at @genefac.

Tags