By Professor Stephen D. Solomon, Editor, First Amendment Watch

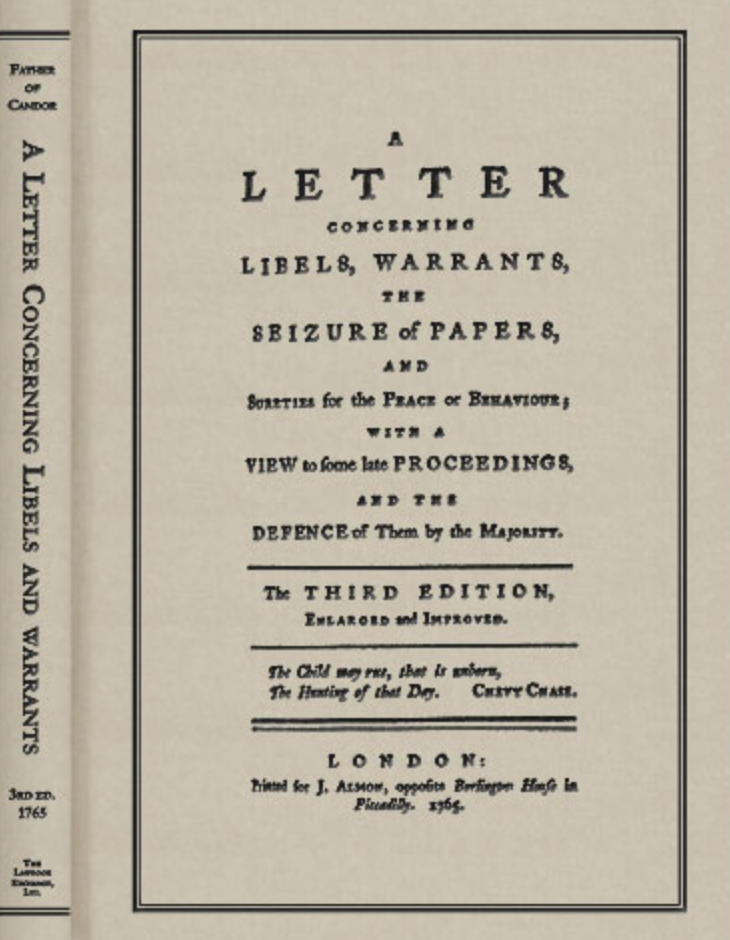

Father of Candor launched one of the most far-reaching attacks on seditious libel, the criminal action that was used to suppress dissenting political speech.

Seditious libel originated in a statute passed by English King Edward I’s Parliament in 1275 that prohibited “any false news or tales whereby discord . . . may grow between the king and his people.” Falsity was a necessary part of seditious libel, but even true libels became part of the crime in 1606, thus subjecting people to penalties for any criticism of officials whether it was true or false. In America, seditious libel was used against dissenters who opposed what they saw as wrongs committed by British officials. With so many Americans protesting against British authority in the decade before Independence, colonial juries came to ignore the crime and refused to indict or convict people for it.

A writer calling himself Father of Candor was far ahead of his time when he attacked seditious libel in 1764. Among his notable contributions to the freedom of speech and press was his argument that “in public libels the truth of the charge should be an absolute defence.” But even proof of truth was not enough to protect freedom of the press. Because erroneous speech is inevitable, even falsity had to be protected unless it was willful falsity. “Now, the merit or demerit of these publications must arise from their being true or false; if they are true, they are highly commendable; if they are willfully false, they are certainly malicious, seditious and damnable,” he wrote.

The U.S. Supreme Court adopted this idea exactly two hundred years later with the “actual malice” test of New York Times v. Sullivan—that a public official in a libel action would have to prove that a defamatory falsehood was published intentionally or with reckless disregard for the truth. (read more below)

Father of Candor’s made other important arguments:

- The “bad tendency” of words to cause harm should not be punished. It is action alone that should be punished. “Sedition cannot be committed by words, but by public and violent action.”

- Libel should not be pursued as a criminal action. “The notion of pursuing a libeller in a criminal way at all, is alien from the nature of a free constitution.”

- Prosecution of libel will chill speech that is critical to good government. “I will venture to prophesy, that if the reigning notions concerning libels be pushed a little farther, no man will dare to open his mouth, much less to use his pen, against the worst administration that can take place, however much it may behove the people to be apprised of the condition they are likely to be in. In short, I do not see what can be the issue of such law, but an universal acquiescence to any men or any measures, that is, a downright passive obedience.”

- Criticisms of public officials are an effective check on their bad actions. “There is one great reason, why every patriot should with this sort of writings to be encouraged; which is, that animadversions upon the conduct of ministers, submitted to the eye of the public in print, must in the nature of the thing be a great check upon their bad actions, and, at the same time, an incentive to their doing what is praiseworthy.”

Father of Candor: A Letter Concerning Libels, Warrants, The Seisure of Papers (Excerpt)

“The writing of any things quietly in one’s study, and publishing it by the press, can certainly be no actual breach of the peace. Therefore, a Member who is only charged with this, cannot thereby forfeit his Privilege.

“I thought that no common man would allow any writing or publishing, especially where extremely clandestine, to be any breach of the peace at all; and that none but the lawyers, on account of the evil tendency sometimes of such writings, had first got them, by construction, to be deemed so. I had no idea that it was possible for any lawyer, however subtle and metaphysical, to proceed so far as to decide mere authorship, and publication by the press, to be an actual breach of the peace, as this last seems to express, ex vi termini, some positive bodily injury, or some immediate dread thereof at least; and that, whatever a challenge, in writing, to any particular might be, a general libel upon public measures, could never be construed to be so. . . .

Richard II King of England

“The notion of pursuing a libeller in a criminal way at all, is alien from the nature of a free constitution. Our ancient common law knew of none but a civil remedy, by special action on the case for damage incurred, to be assessed by a jury of his fellows. There was no such thing as a public libel known to the law. It was in order to gratify some of the great men, in the weak reign of Richard II that some acts of parliament were passed to give actions for false tales, news, and slander of Peers or certain great officers of state, which are termed de scandalis magnatum. . . .

“The whole doctrine of libels, and the criminal mode of prosecuting them by information, grew with that accursed court the star-chamber. All the learning intruded upon us de libellis famosis was borrowed at once, or rather translated, from that slavish imperial law, usually denominated the civil law. You find nothing of it in our books higher than the time of Q. Elizabeth and Sir Edward Coke.

“But if any writing should be a libel, and be prosecuted only as such, it is in vain afterwards to call it ‘abominable or treasonable,’ with any idea that such epithets will warrant an extraordinary proceeding in the prosecutor. This end indeed it may answer, and a very diabolical one it is; it may serve to found a pretence for demanding excessive bail, which if the supposed libeller cannot find he must lie in prison . . .

“It has been resolved, ‘That sedition cannot be committed by words, but by public and violent action.” . . .

“I will venture to prophesy, that if the reigning notions concerning libels be pushed a little farther, no man will dare to open his mouth, much less to use his pen, against the worst administration that can take place, however much it may behove the people to be apprised of the condition they are likely to be in. In short, I do not see what can be the issue of such law, but an universal acquiescence to any men or any measures, that is, a downright passive obedience.

“There is one great reason, why every patriot should with this sort of writings to be encouraged; which is, that animadversions upon the conduct of ministers, submitted to the eye of the public in print, must in the nature of the thing be a great check upon their bad actions, and, at the same time, an incentive to their doing what is praiseworthy. Nevertheless, if it be once clear law, That a paper may be a libel, whether true or false, written against a good or bad man, when alive or dead, who is there that may not continue a Minister, whether he has a grain of honesty or understanding, if he should happen to be a Favourite at Court? The worse his actions are, the more truly and sharply the writer states them; and the more the public, from his just reasoning’s, detest and cry out against them, the more scandalous and seditious of course, will be the libel; for, the truth of the fact is an aggravation of the libel; and it was that which occasioned the clamour. There is but one step farther before you arrive at complete despotism, and that is to extend the same doctrine to words spoken, and this I am persuaded would in truth very soon follow. And then what a blessed condition should we all be in! when neither the liberty of free writing or free speech, about everybody’s concern, about the management of public money, public law and public affairs was permitted; and every body was afraid to utter what every body however could not help thinking! . . .

“There is one great reason, why every patriot should with this sort of writings to be encouraged; which is, that animadversions upon the conduct of ministers, submitted to the eye of the public in print, must in the nature of the thing be a great check upon their bad actions, and, at the same time, an incentive to their doing what is praiseworthy. Nevertheless, if it be once clear law, That a paper may be a libel, whether true or false, written against a good or bad man, when alive or dead, who is there that may not continue a Minister, whether he has a grain of honesty or understanding, if he should happen to be a Favourite at Court? The worse his actions are, the more truly and sharply the writer states them; and the more the public, from his just reasoning’s, detest and cry out against them, the more scandalous and seditious of course, will be the libel; for, the truth of the fact is an aggravation of the libel; and it was that which occasioned the clamour. There is but one step farther before you arrive at complete despotism, and that is to extend the same doctrine to words spoken, and this I am persuaded would in truth very soon follow. And then what a blessed condition should we all be in! when neither the liberty of free writing or free speech, about everybody’s concern, about the management of public money, public law and public affairs was permitted; and every body was afraid to utter what every body however could not help thinking! . . .

“Now, my notion is, that in public libels the truth of the charge should be an absolute defence, whatever may be thought necessary with regard to private libels. The public is essentially interested in this discrimination being made.

“When men find themselves aggrieved by the violence or the misconduct of the persons appointed to the Ministry, it is natural for them to complain, to communicate their thoughts to others, to put their neighbors on their guard, and to remonstrate in print against the public proceedings. They have a right so to do, as much as a borough has a right to reject any Court candidate, and to publish the reasons for so doing; and both these rights will I hope be exercised . . .

Benjamin Franklin 1767

“…The liberty of exposing and opposing a bad Administration by the pen is among the necessary privileges of a free people, and is perhaps the greatest benefit that can be derived from the liberty of the press. But Ministers, who by the misdeeds provoke the people to cry out and complain, are very apt to make that very complaint the foundation of new oppression, by prosecuting the same as a libel on the State. Now, the merit or demerit of these publications must arise from their being true or false; if they are true, they are highly commendable; if they are willfully false, they are certainly malicious, seditious and damnable. The mere pretence of a paper being seditious, if the matter of it be fact, is to be disregarded; for I do not see how any writer can publish to the world the justest and most important complaints, without tending thereby to render the people and their constituents dissatisfied with the administration, and even clamorous against it. Nay, I scarcely can frame to myself any other way of letting his Majesty know that the ministry he has appointed is bad. However, if a minister notwithstanding should continue a favourite at Court, and the people being affected with what was written should clamour, and have great reason for so doing, I make no doubt but that any Attorney-General would file an information against the Writer, and charge him at once with endeavoring to alienate the affections of the people, and to raise traitorous insurrections against the peace of the King; altho’ it were obvious to every indifferent person, that the unlucky writer had no such intention, nay, had been ready on a former occasion voluntarily to associate for the defence of his Majesty’s title, and to venture his life in the field to support it. Indeed I am fully convince, that were it not for such writings as have been prosecuted by Attorney-generals for libels, we should never had had a Revolution, nor his present Majesty a regal Crown; nor should we now enjoy a protestant religion, or one jot of civil liberty. Kings can hardly receive any intelligence but what their ministers give them, and these gentlemen, being generally guided by avarice and ambition, endeavour to represent every man who strives to get them dismissed from their employs, as one who is about to attack the throne itself, call him traitor directly, and then exert the power of the crown to demolish him.”

Source: Father of Candor, A Letter Concerning Libels, Warrants, The Seisure of Papers . . . 7th ed. (London: J. Almon, 1771), 16-17, 46-49, 161

READ MORE:

Tags