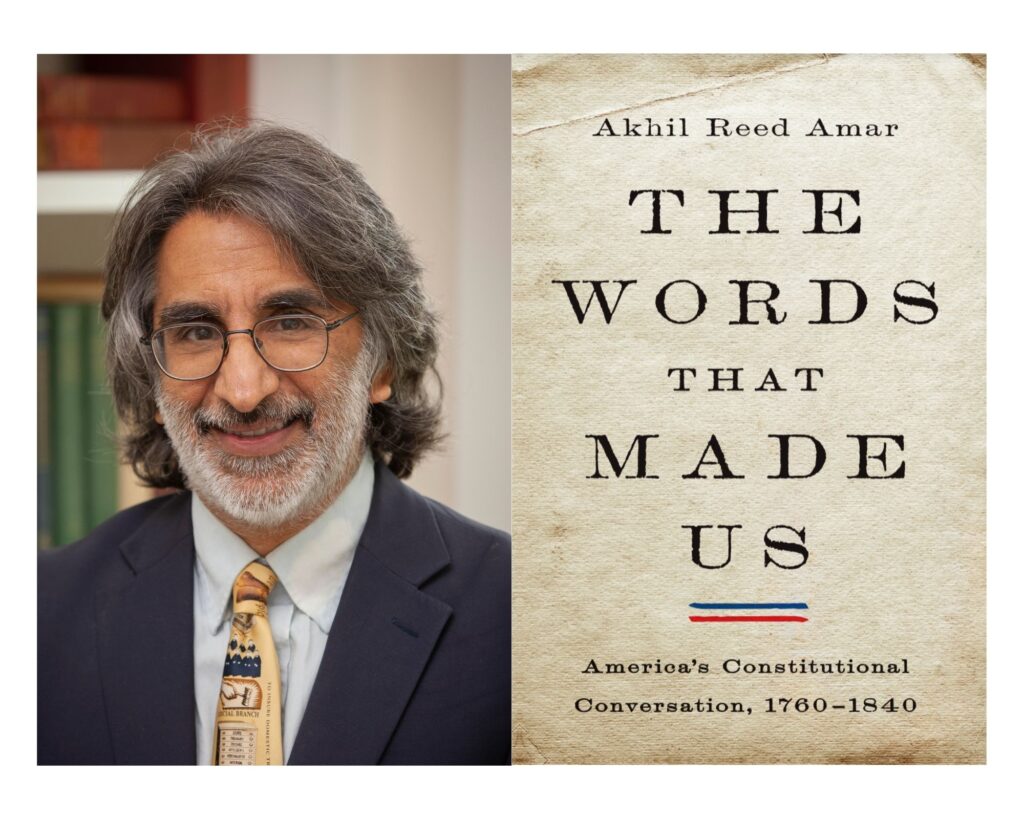

In his newest book, The Words that Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation 1760-1840, Yale law professor and constitutional historian Akhil Reed Amar tells the story of the first 80 years of democratic debate in the United States. In the author’s words, the book shows how “various widely scattered New Worlders first became Americans and then continued to debate and refine what being American meant.” Even after the states ratified the Constitution, many questions still consumed public debate and discussion. For example, what role should the judiciary play in government—did it possess the power of judicial review of acts of the legislature? Should the country allow slavery in the new territories? Should the federal government create a national bank? Amar parachutes into the thick of these debates using the letters, essays, treatises, and cartoons that gave color to this robust national conversation.

This excerpt focuses on the origins of America’s newspaper culture and the central role it played in forming our democracy. Before America gained its independence, printers tested the limits of British rule by defying the Stamp Act of 1765. Once Americans were free to create their own government, elected officials relied on newspapers to circulate state constitutions and publish public opinion on issues of the day. Although it is only a fraction of Amar’s 800-page book, this excerpt manages to convey a strong message: there would likely have not been any “constitutional conversation” had there not been a vibrant and healthy press to foster it.

Akhil Reed Amar is the Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University, where he teaches constitutional law in both Yale College and Yale Law School. He is the author of more than 100 law review articles and several books, most notably The Bill of Rights, America’s Constitution, America’s Unwritten Constitution, The Constitution Today, and now The Words that Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840 which is now available for purchase on Amazon or Barnes and Noble.

This excerpt was published with the permission of Akhil Reed Amar and Basic Books publishing.

Stamps, Paper, and the Press

An illustration of colonists denouncing the Stamp Act of 1765. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In the 1765 Stamp Act crisis, colonial newspapers across the continent went about their business as usual—sometimes without any interruption, sometimes after an initial wait-and-see pause in operations—openly churning out edition after edition on unstamped paper. Most colonial newspapers continued to overflow with ink against the act; and the very pieces of paper on which this ink appeared also spoke volumes. Even though Parliament had not slyly designed the Stamp Act as a purposeful attack on the colonial press, the act had indeed burdened businesses that were based on paper itself—most notably, newspaper printers.

Thus, in addition to the act’s open violations of proper principles of taxation and representation (as Americans understood these principles) and its insidious assault on jury trial rights (thanks to its vice-admiralty enforcement rules), the act also was an indirect imposition on freedom of the press. Suppose a future ministry refused to sell stamps or stamped paper to a given opposition newspaper. Could the Stamp Act, with modest tweaking, deteriorate into a regime of official censorship and press licensing? Of all the things in the world that Parliament might have chosen to tax—carriages, cloth, coffee, linen, liquor, lumber, tallow, tar, tea, you name it—British lawmakers had unwisely chosen to tax an item vital to discourse itself, especially discourse aiming to span significant physical distance. Colonial printers thus pushed back hard. Unwittingly, the act enabled them to mock Parliament simply by ignoring it and doing what the press had always done: print words on paper.

Although the vast majority of the colonists’ rhetorical cannons in 1764–1765 aimed directly at the issues of Parliamentary taxation and constitutional jury rights, one anonymous essayist in the October 21, 1765, edition of the Boston Gazette offered his readers an astute, if unduly conspiratorial, aside on the broader issues of press freedom and public discourse: “It seems very manifest from the S—p A-t itself, that a design is form’d to strip us in a great measure of the means of knowledge, by loading the Press, the Colleges, and even an Almanack and a News-Paper, with restraints and duties.” Perhaps inspired by this aside, a newspaper in neighboring Connecticut came out as scheduled on November 1—the Stamp Act’s operative date—and did so on unstamped paper with an open editorial ode to “the press” as “the test of truth, the bulwark of public safety, [and] the guardian of freedom.” The anonymous and perhaps inspirational Gazette essayist was none other than John Adams, then a week shy of his thirtieth birthday and readying himself to play an increasingly public role in the great scenes unfolding all around him.

The Details of Press Pushback, From North to South

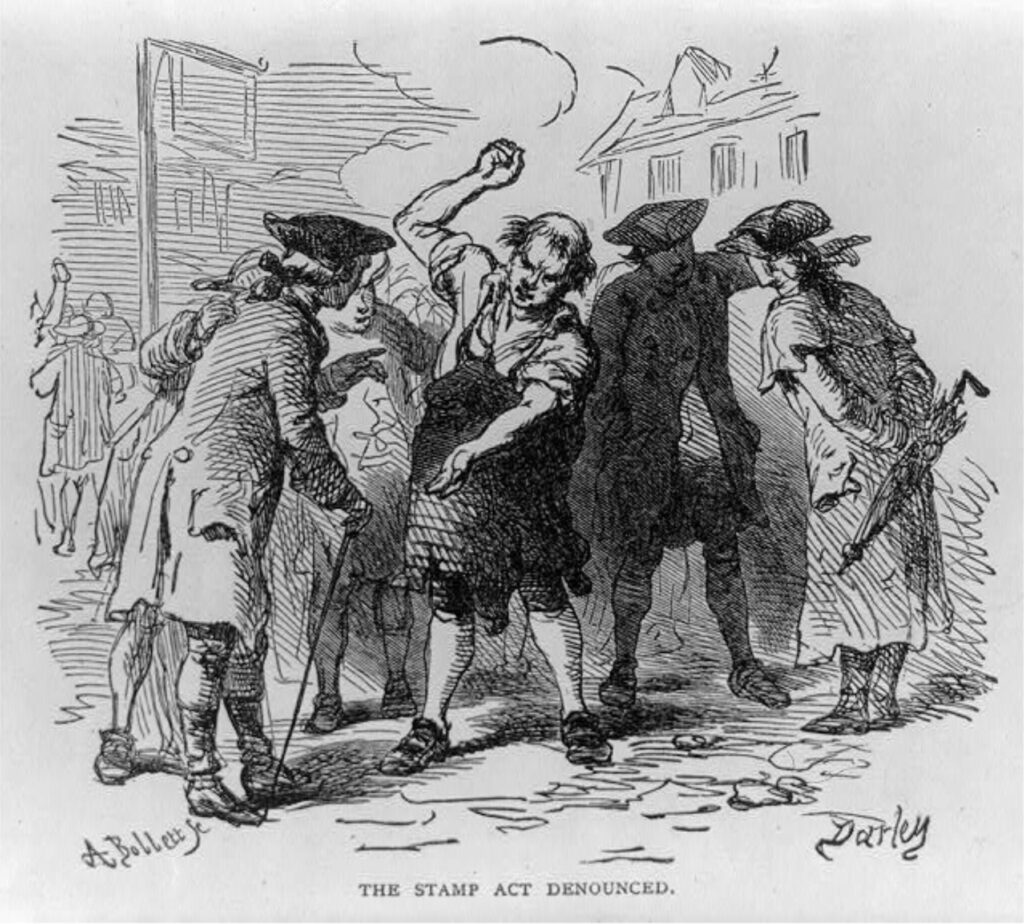

To cover the costs of the Seven Years’ War, Britain passed a law that required printed materials to have a tax stamp. Many colonial newspapers defied the law and printed newspapers without stamps, including the New Hampshire Gazette (top left) The Boston Post Boy & Advertiser (top right), The Boston Evening Post (bottom left), and the New London Gazette (bottom right). Images from The Words that Made Us.

In Portsmouth, the New-Hampshire Gazette published a day early, on Oct. 31, 1765, with a special explanatory masthead announcement: “This is the Day before the never-to-be-forgotten STAMP-ACT was to take Place in America.” The following week and thereafter, the Gazette came out on time and unstamped, but did omit its customary colophon identifying printers Daniel and Robert Fowle. Their names returned only mid-May 1766, post-repeal.

In Boston, Benjamin Edes and John Gill’s Boston Gazette, closely affiliated with the emerging Sons of Liberty, defiantly cranked out editions without pause, without modification, and without stamps (but with the customary colophon), beginning, as scheduled, on Nov. 4. By contrast, Richard Draper’s Crown-supported Boston News-Letter (“Printer to the Governor and Council”) changed its masthead after Nov. 1, 1765, dropped its Draper-identifying nameplate, and operated as the Massachusetts Gazette, officially returning as the News-Letter on May 22, 1766, post-repeal.

The Boston Post-Boy published weekly without interruption but omitted from its Nov. 4 and 11 nameplate the usual “Published by Green & Russell, Printers to the Honourable House of Representatives.” From Nov. 18, 1765, through April 14, 1766, the following truculent words appeared in their place: “The united Voice of all His Majesty’s free and loyal Subjects in america,—liberty and property and no stamps.”

The Boston Evening-Post did much the same thing—publishing as usual on Nov. 4 and 11, 1765, and then adding the same new truculent words beneath the masthead beginning Nov. 18, but only for three editions, through Dec. 2, then back to the pre–Stamp Act format. The colophon identifying publishers Thomas and John Fleet disappeared in Nov. and reappeared post-repeal. Also, on Nov. 18, the Evening-Post’s truculent addition expressly credited the New-York Gazette for the inspirational slogan—compelling evidence of thickening intercolonial conversation among printers.

In Newport, the Newport Mercury carried on without stamps or interruption, but its first two post–Stamp Act editions, on Nov. 4 and 11, omitted printer Samuel Hall’s colophon. In New London, Timothy Green’s New-London Gazette bravely published unstamped beginning on D-Day itself, Nov. 1.

On Nov. 15, the Gazette dropped its old masthead featuring the British lion and unicorn. In its stead, the mid-month masthead in its entirety read: “Liberty and Property, and no stamps”—an abridged version of the truculent slogan that had already appeared in Manhattan to the South and would soon appear in Boston to the North.

After an apparent month-long pause, December editions returned to the old masthead label, New-London Gazette, but the lion and unicorn were gone for good.

In Hartford, Timothy’s brother Thomas Green suspended publication of the Connecticut Courant in November, but resumed, unstamped, in December with a different look.

In New York, the newspaper that had originated the truculent slogan, John Holt’s New-York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy, printed without interruption and without stamps. The New-York Mercury ran three disguised early and mid-November editions that hedgingly replaced the usual masthead with “No Stamped Paper to be had”; and returned to the old masthead when the coast seemed clear on Nov. 25.

Mercury printer Hugh Gaine’s name reappeared on Dec. 2, and his proud nameplate returned to its usual place below the masthead on Dec. 9. William Weyman’s New-York Gazette (not to be confused with Holt’s similarly named publication) had closed down for much of the fall; in December, it resumed operation, unstamped.

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Gazette printer David Hall mournfully told readers on Oct. 31, in a third-page paragraph framed by thick black obituary bars, that “the most unconstitutional act that ever these Colonies could have imagined . . . is feared to be obligatory upon us after . . . the fatal tomorrow.” The newspaper would thus “stop a While, in order to deliberate whether any Methods can be found to elude the Chains . . . and escape the insupportable Slavery.”

After a week off, Hall (who had taken over from Gazette founder Franklin) issued an irregular mid-November edition with a hedged “No Stamped Paper to be had” masthead exactly mirroring (including the selective italics) the New-York Mercury—additional compelling evidence of close journalistic conversation across colonies.

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Gazette printer David Hall mournfully told readers on Oct. 31, in a third-page paragraph framed by thick black obituary bars, that “the most unconstitutional act that ever these Colonies could have imagined . . . is feared to be obligatory upon us after . . . the fatal tomorrow.”

On Nov. 21, the Gazette resumed publishing openly as before, unstamped; Hall at first dropped his identifying colophon, and then restored it in February.

William Bradford’s Pennsylvania Journal also came out unstamped in November and thereafter, after warning readers on Oct. 31 of a suspension in wording almost identical to Hall’s (“the Fatal To morrow . . . stop awhile . . . deliberate . . . Methods . . . elude . . . Chains . . . Slavery”). That day’s masthead mocked the act with a fake skull-and-crossbones stamp (following a similar mock-up at the bottom of the front page the previous week) and proclaimed that the paper was “EXPIRING: in Hopes of a Resurrection to LIFE again.”

In Williamsburg, Alex Purdie’s Virginia Gazette, after a long pause, resumed publication (stampless, of course) on March 7, and a new publication—Rind’s Virginia Gazette, named for its printer, William Rind—commenced stampless publication on May 16. In Savannah, the Georgia Gazette published three unstamped editions, on Nov. 7, 14, and 21. On the 14th, proto-loyalist printer James Johnston announced that he “was under the necessity of putting a stop to the publication.” The following week came this update: “NOTWITHSTANDING our advertising last week that a stop was put to the publication of this Gazette, we shall continue printing the same as long as we are allowed to make use of unstampt paper.” But no further editions issued until the repeal of the Stamp Act.

The Framers as Newspapermen

A young Benjamin Franklin depicted in his Philadelphia printing shop. Painting by Arthurs, S.M, unknown date. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that all the great founding fathers were early sires and children of America’s emerging newspaper culture. By modern consensus, history’s “Big Six” founders are America’s first four presidents—Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison—plus Franklin and Hamilton.

Franklin was a self-made printer and popular writer who amassed a fortune before age forty by creating what we would today call a media empire—a string of affiliated print shops and paper mills across the continent.

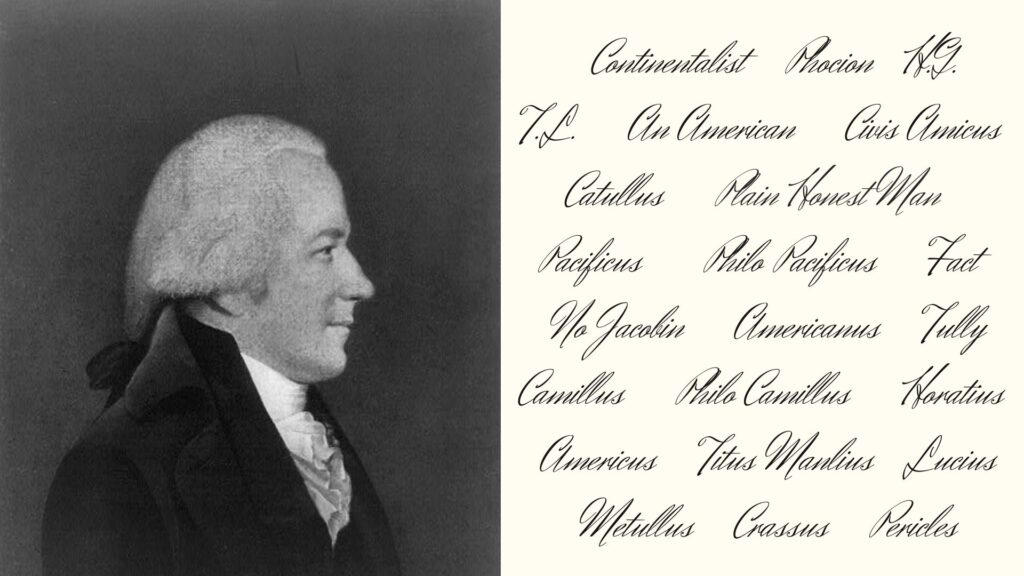

Hamilton published his first notable newspaper piece, a compelling description of a tropical hurricane, while a mere lad in the West Indies. This was his first big break in life—the vivid piece of prose brought him to the attention of patrons who financed his emigration to the mainland. While still a college student, he then published precocious patriot pamphlets and newspaper essays that eventually helped bring him alongside Washington as the general’s scribe and right hand Thereafter he went on to become a newspaperman extraordinaire, as exemplified by his brilliant performance as Publius and in scores of other essays before and after, published under a dizzying array of pen names: Continentalist, Phocion, H.G., T.L., An American, Civis, Amicus, Fact, Catullus, Metullus, Plain Honest Man, Pacificus, Philo Pacificus, No Jacobin, Americanus, Tully, Camillus, Philo Camillus, Horatius, Americus, Titus Manlius, Lucius Crassus, Pericles, and perhaps more.

In his mid-thirties, Madison teamed up with Hamilton in newspapers, and in his early forties, Madison turned against Hamilton in newspapers. In one six-month period in 1791–1792, the Virginia politico produced some fifteen short pseudonymous essays for a single newspaper, Philip Freneau’s National Gazette. Before his debut on the national stage, Madison had brilliantly championed religious freedom in his home state via a punchy and anonymous printed circular, his acclaimed “Memorial and Remonstrance.”

After returning from France, Jefferson quietly created a partisan newspaper network of his own, partly financed with other people’s money—a masterstroke. Long before that, in his early thirties, Jefferson had published an important 1774 pamphlet articulating the dominion theory of empire.

Writing as “Novanglus,” Adams published similar newspaper pieces making similar arguments at about the same time, building on prior newspaper submissions stretching back to the mid-1760s, when the Braintree lawyer was still in his late twenties. Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin of course also crafted the Declaration as a poetic and punchy piece for newspaper distribution.

To sum up: five of the big six were newspaper scribblers, early and often.

The many pseudonyms of Alexander Hamilton. Portrait (L) from the Library of Congress.

Washington might at first seem the odd man out, because he did not write nearly so much for public consumption about the great constitutional issues of his era after the onset of the imperial crisis in the early 1760s. He was not a printer (like Franklin), a lawyer (like Adams, Jefferson, Hamilton, Jay, and Wilson), or an amateur scholar (like all of the above, plus Madison). Rather, Washington was a gentleman surveyor-planter-entrepreneur-investor-soldier-administrator. In 1775–1776, he could not devote himself to legal and political theorizing because he was attending to other matters of some importance. In 1788, he maintained an official silence and let his chief lieutenants, whom he quietly encouraged and abetted—Hamilton, Madison, Wilson, Randolph, and Marshall—make the public case for the document that reflected his vision more than anyone else’s.

On closer inspection, Washington was in fact as much a newspaperman as the others—probably a more prodigious newspaper reader, though doubtless a less prolific newspaper writer. Throughout his career, he proved himself exquisitely attentive, as he had been since 1754—when Adams was an unknown, Jefferson a mere schoolboy, Madison a toddler, and Hamilton perhaps a fetus—to his public image in America’s increasingly continental press.

Read the full book :”The Words that Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840”

About the Author: Akhil Reed Amar

Akhil Reed Amar is the Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University, where he teaches constitutional law in both Yale College and Yale Law School. After graduating from Yale College, summa cum laude in 1980, from Yale Law School in 1984, and clerking for then Judge (now Justice) Stephen Breyer, Amar joined the Yale faculty in 1985 at the age of 26. He is Yale’s only currently active professor to have won the University’s unofficial triple crown — the Sterling Chair for scholarship, the DeVane Medal for teaching, and the Lamar Award for alumni service.

He is the author of more than 100 law review articles and several books, most notably The Bill of Rights (1998 — winner of the Yale University Press Governors’ Award), America’s Constitution (2005 — winner of the ABA’s Silver Gavel Award), America’s Unwritten Constitution (2012 — named one of the year’s 100 best nonfiction books by The Washington Post), and The Constitution Today (2016 — named one of the year’s top 10 nonfiction books by Time magazine). His latest book, The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840, is due out in May 2021. He has recently launched a weekly podcast, Amarica’s Constitution. A wide assortment of his articles, op-eds, and video links to many of his public lectures and free online courses may be found at akhilamar.com.

Tags