In “Actual Malice: Civil Rights and Freedom of the Press in New York Times v. Sullivan,” Samantha Barbas “unfurls the story of the case and reminds readers that the triumph of press freedom was an outgrowth of the civil-rights struggle … Her book illuminates the effect of libel suits on journalists’ ability to cover the movement, the legal strategies used against those suits, and the impact of the case on the civil-rights movement itself. A heroic narrative in which the litigation helped vanquish segregationists serves to underscore what Barbas calls the ‘centrality of freedom of speech to democracy.'” — The New Yorker

Samantha Barbas is a professor of law at the University of Buffalo School of Law. Barbas holds a Ph.D. in history from the University of California at Berkeley and a J.D. from Stanford Law School. She has authored seven books on mass media law and history, including “The Rise and Fall of Morris Ernst: Free Speech Renegade” which was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2021, and “Confidential Confidential: The Inside Story of Hollywood’s Notorious Scandal Magazine,” which was published by Chicago Review Press in 2018.

Samantha Barbas — “Actual Malice: Civil Rights and Freedom of the Press in New York Times v. Sullivan“

From “Actual Malice” by Samantha Barbas, published by University of California Press. Copyright © 2023 by Samantha Barbas. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Adaptation of Chapter 12, “Herbert Wechsler,” pages 158-166.

It was indeed a moment of reckoning at the New York Times. The newspaper confronted millions of dollars in liability and the possibility of bankruptcy. Would it appeal to the Supreme Court? Or would it settle, in violation of the Ochs policy?

The top brass began to think that settlement was the only option—if the Alabama officials would in fact settle, which wasn’t clear. An appeal to the Supreme Court would be phenomenally expensive, and the law wasn’t on their side.

For one of the first times in the history of the newspaper, the hardheaded, fight-to-the-end leaders of the Times were ready to call it quits in a libel case. And it was Louis Loeb who stopped them. Loeb had always advocated the cautious, conservative route, but this time he wasn’t sure that the Times should give in. The Ochs policy had been established for a good reason. If the Times caved in, who else would sue the paper for millions? Would segregationists, in the next round or two of libel suits, sue the New York Times out of existence? Loeb told the executives that the future of the paper was on the line and that they had to take a chance.

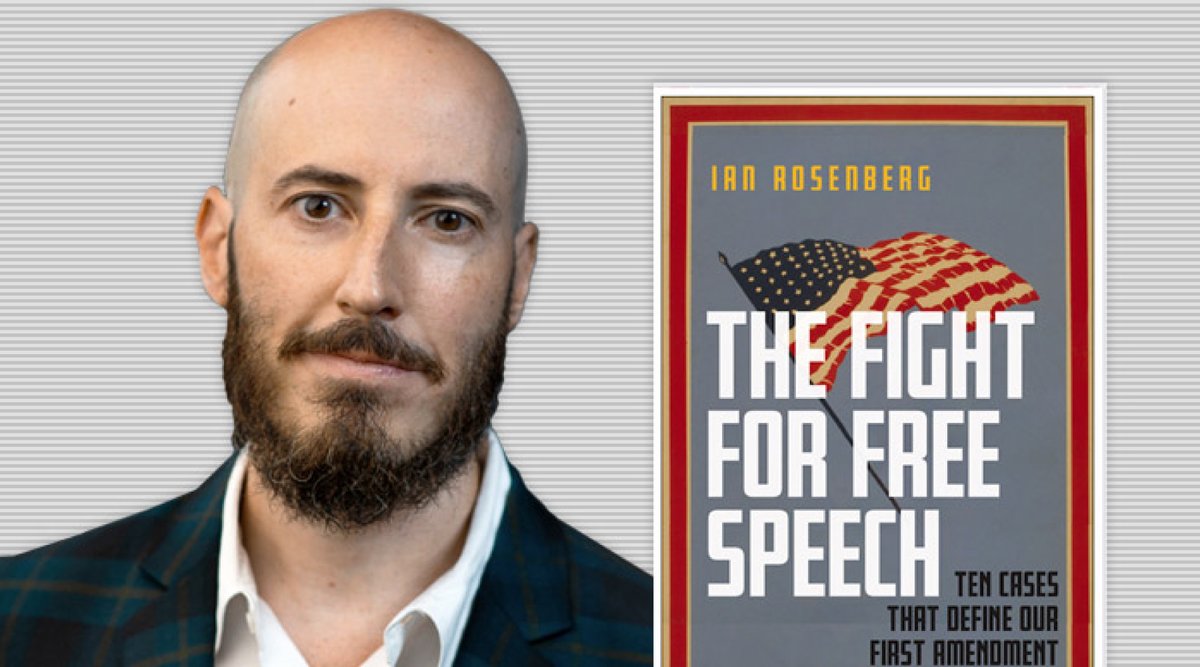

The Times leaders weren’t convinced, but they gave him the authority to seek the advice of a constitutional law expert. Loeb called Herbert Wechsler of Columbia Law School, one of the most prominent academic lawyers in the country. The Times’ decision to use its prestige to employ Wechsler was one of the most important in the history of the Times and perhaps even in the history of journalism.

• • • • •

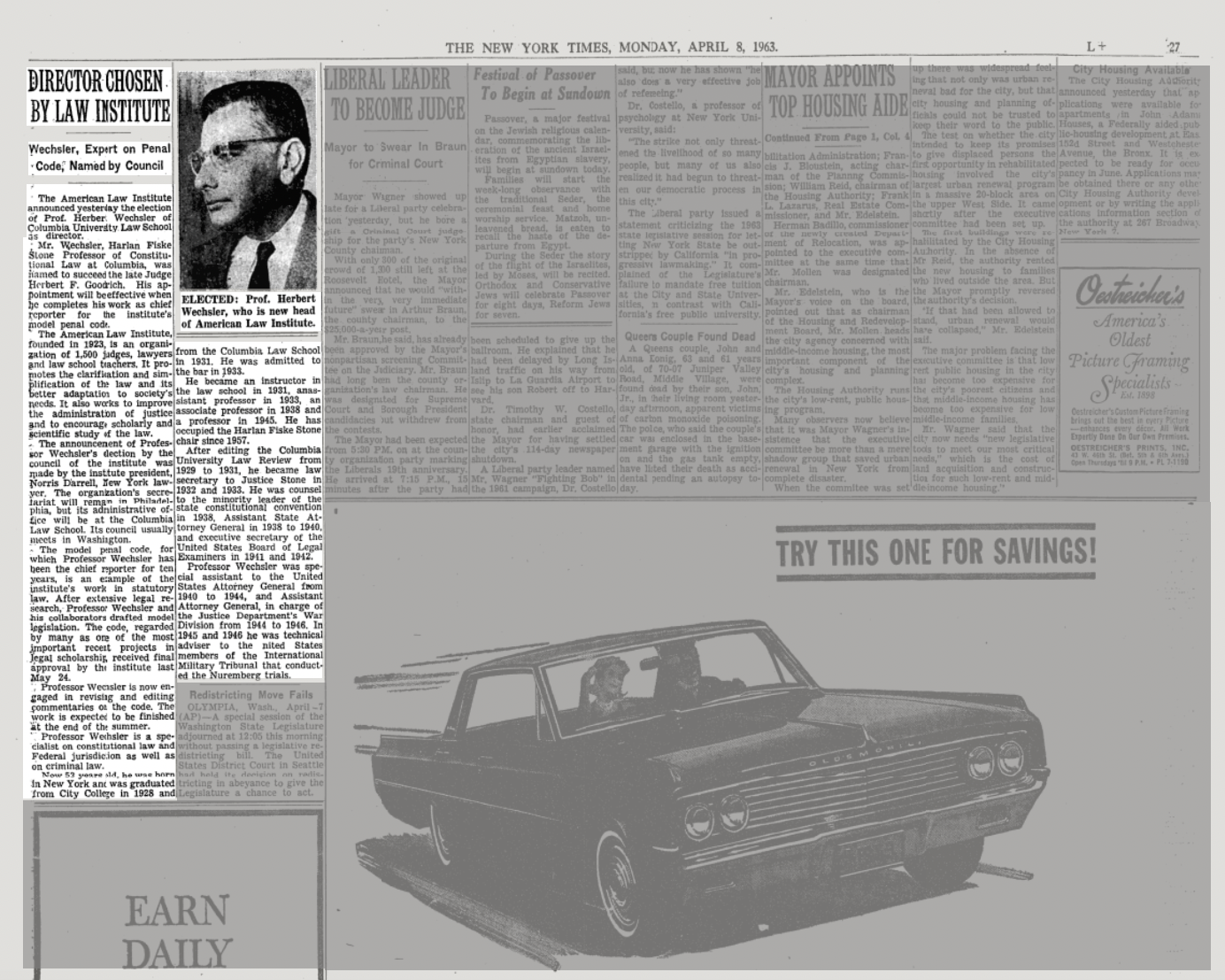

The New York Times reports on Columbia Law School Professor Herbert Wechsler’s election as director to the American Law Institute April 8, 1963. (The New York Times)

In 1962, fifty-two-year-old Wechsler stood at the top of three fields: constitutional law, criminal law, and federal courts. Wechsler had argued a dozen cases before the Supreme Court, served in the Department of Justice, written influential law review articles, and authored for the American Law Institute the Model Penal Code, which would be used as a guide by state legislatures to create their criminal codes. Shortly after the Sullivan case, Wechsler began a lengthy term as director of the American Law Institute. It was without exaggeration that he was dubbed a “modern-day Blackstone.”

Wechsler was short and sturdily built, with thick eyebrows and a stern gaze. His voice was deep and nasal, with a strong, pinched New York accent. His piercing intellect, caustic remarks, and robust sense of self-importance intimidated colleagues and students alike. When one of his students exhibited superficiality in posing a question or answer in one of his classes, he would exclaim: “That remark betrays not the slightest degree of cerebration!” A colleague once described Wechsler’s ability to cut the heart out of an argument before the speaker even realized that they had more than a flesh wound.

• • • • •

Wechsler had been groomed for a life of the mind. Wechsler was born in 1909 in the Bronx to a middle-class Jewish family that prized literacy and learning. His grandfather, an immigrant from Hungary, had been a rabbi and journalist, and his father was a lawyer. His younger brother, James, became a celebrated and controversial editor for the New York Post.

Wechsler attended public elementary and high schools in New York and graduated from City College at the age of nineteen. Determined to become a French teacher—an unusual aspiration for a prodigy—he applied to teach French at City College. The application was rejected because his father convinced the department head that his son should be a lawyer instead of a French teacher. In an interview late in his life, Wechsler avowed that he would have been “a colossal flop” as a French instructor and was grateful that he’d been saved from that “misfortune” by his father.

Wechsler graduated from Columbia Law School during the depths of the Great Depression in 1931. He took a teaching position at Columbia briefly, then headed to Washington to pursue a prestigious clerkship with Supreme Court justice Harlan Fiske Stone. Stone became a role model for Wechsler, who praised his vigorous defense of judicial review and his embrace of a flexible, “living Constitution.”

It was during his Supreme Court clerkship that Wechsler first witnessed the intensity of racial animus in the South. Only weeks after he arrived in Washington, the Court heard an appeal from the Communist affiliated International Labor Defense in the Scottsboro case. Wechsler was so moved by the wrongful conviction of the Scottsboro Boys that he published a piece in the Yale Law Journal calling for a federal “reconstruction” of the South, including anti-lynching legislation. Wechsler saw how the suppression of speech could be used to further racial oppression. In 1935, the International Labor Defense invited Wechsler to work on the case of Herndon v. Lowry, involving a black Communist Party organizer convicted by the State of Georgia of attempting to incite insurrection. In Herndon, a landmark in First Amendment law, the Court used the clear and present danger rule to strike down the Georgia insurrection statute.

By the time he was in his early thirties, Wechsler had accrued a string of accomplishments that most never approached in their lifetimes. He became a professor at Columbia, co-authored the longest article ever written on homicide, and co-wrote a monumental casebook on criminal law. In 1941, Wechsler took a sabbatical and went to work in the Office of the Solicitor General, where he spent the year arguing cases for the government in the Supreme Court. From 1944 to 1946, Wechsler served as assistant attorney general in charge of the War Division. He argued the unpopular case of Korematsu v. United States before the Supreme Court, which upheld the internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry, and continued to defend the case long after it was discredited. At the close of the war, Wechsler served as a key advisor to the judicial tribunal at Nuremberg.

Wechsler returned to Columbia and recommenced his brilliant and productive academic career. He co-authored, with Professor Henry M. Hart of Harvard, one of the most influential American legal casebooks, The Federal Courts and the Federal System. In 1950, Wechsler drafted the Model Penal Code. Another of Wechsler’s achievements was his 1959 article in the Harvard Law Review, “Toward Neutral Principles of Constitutional Law,” one of the most cited law review articles of all time. The work is referenced as an exemplar of the legal process school of thought, which believes that the evaluation of judicial review should focus not on interests or values served by the decision but rather the method of decision.

Wechsler agreed with the result of Brown but contested the reasoning behind the decision. He believed that Brown and the Warren Court’s other decisions on race were inadequately “principled.” Brown raised an issue of “competing freedoms: freedom to associate and freedom not to associate,” he wrote. Was there “a basis in neutral principles for holding that the Constitution demands that the claims for association should prevail”? He believed that his conclusion was helping, rather than hurting, the cause of civil rights. If guided by neutral principles, constitutional adjudication was likely to be consistent, and as a result, to command greater respect, than if guided by considerations of policy. Wechsler was an ardent defender of racial equality, although the article gave the impression that Wechsler opposed civil rights, and it contributed along with Korematsu to Wechsler’s mixed legacy among liberals.

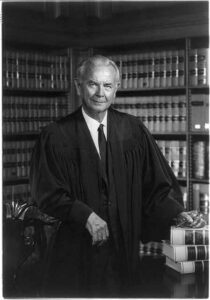

A 1972 portrait of U.S. Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., author of the New York Times v. Sullivan opinion. (Library of Congress/Robert S. Oakes)

Wechsler was immediately intrigued by Loeb’s proposal to help the New York Times appeal the Sullivan case. Wechsler was intellectually engaged by the issues; he also, frankly, needed the money. Wechsler was supporting two sick parents and an ex-wife at the time. (The Times would pay Wechsler $40,000 for his work on the case, underscoring how a newspaper of lesser standing and means could never have afforded such legal talent.) Wechsler had recently started a consulting law practice for extra income. He served as a consultant to Lord Day & Lord in connection with various libel suits and had advised CBS on libel cases.

Through this work for media outlets, Wechsler had begun contemplating the maxim that libel was “outside” the First Amendment. He knew there had been important Supreme Court decisions that brought formerly excluded areas of speech under the First Amendment’s protections. Bridges v. California (1941) held that the First Amendment protected critical statements about judges that had once been punishable as contempt. Pornography had once been totally excluded from the First Amendment until Roth v. U.S. (1957). Wechsler believed that the time had come to bring libel law in line with these developments. “The Supreme Court could not on one hand be sensitive to First Amendment claims in practically every area of speech and expression . . . and still take the view that defamation was not an area to be treated in the same way,” he believed.

It was with these thoughts in mind that Wechsler met Loeb to discuss the Sullivan case. Loeb explained that there was “great resistance” in Times headquarters to appealing the case on First Amendment grounds. The Times had never lost a libel case that hadn’t been reversed or otherwise ended up in a favorable way for the Times, and they were reluctant against that background to risk their prestige, Loeb said. At the end of the meeting, Loeb told Wechsler that the decision to appeal had to be made by the leaders of the Times. He asked Wechsler to come to a gathering in the Publisher’s Dining Room to discuss the issue. It was, Wechsler recalled, “one of the most important meetings I ever attended.”

• • • • •

The Publisher’s Dining Room on the eleventh floor was the prestigious inner sanctum of the Times. The managerial staff lunched there on shrimp and steak, served on gold-rimmed china plates. Presidents, foreign leaders, industrialists, and other dignitaries attended these luncheons. The walls were embossed with an eagle, the New York Times’ emblem. Distinguished guests were assured by Sulzberger, who never tired of puns, that anything they said was sub rosa (the ceiling was decorated with roses).

When Wechsler walked in at noon on Tuesday, November 6, 1962, he saw all the top brass at the table—John Oakes, editor of the editorial page, Orvil Dryfoos, Clifton Daniel, Harrison Salisbury, Turner Catledge, Harding Bancroft, Lester Markel, the Sunday editor, and Arthur Krock. Arthur Hays Sulzberger was seated on the side, in a wheelchair. Wechsler described it as a “council of war.”

Wechsler explained the history of the Alabama cases and the legal issues involved. The facts of the case could be very “sympathetic” to the Supreme Court, he said. Wechsler then proceeded to embark on a kind of “law school lecture,” as he put it, to tell the newspaper officials “what had happened regarding the judicial interpretation of the First Amendment over the preceding thirty years.” He explained how the Court had taken previously unprotected areas of speech like pornography and contempt and subjected them to judicial scrutiny and constitutional standards. The time was now ripe to bring libel under the First Amendment, he argued. Wechsler told the executives that the Times owed it to itself and to the newspaper profession not to pass up the opportunity to pursue the First Amendment claim. He asked, “If the Times didn’t take this [argument] up in what was overall a very significant case who could be expected to make it?”

Several of the men aggressively questioned Wechsler. Wouldn’t it be better to settle the case out of court? What was the likelihood of reversal? A few, including Harrison Salisbury, seemed receptive to Wechsler’s arguments. They finished their lunches, and Wechsler left. He could see that he hadn’t convinced most of them. But he felt confident that he did win over the most important man in the room, publisher Orvil Dryfoos. Shortly after, Dryfoos met with Loeb, and Loeb called Wechsler and told him to seek Supreme Court review.

The Times was betting it all on Wechsler, who thereafter became the lead attorney on the case. Of course, this was a good bet. Yet what lay ahead, even for a scholar and advocate of Wechsler’s stature, was daunting. Even Wechsler wasn’t sure he could win. He was confident of his intellectual powers and his knowledge of law, but he was uncertain that he could convince the Court to make a sweeping change in its position on libel and the First Amendment. For the Court to conclude that the traditional, well-established doctrines of libel law violated constitutional guarantees of free speech would be a remarkable leap.

• • • • •

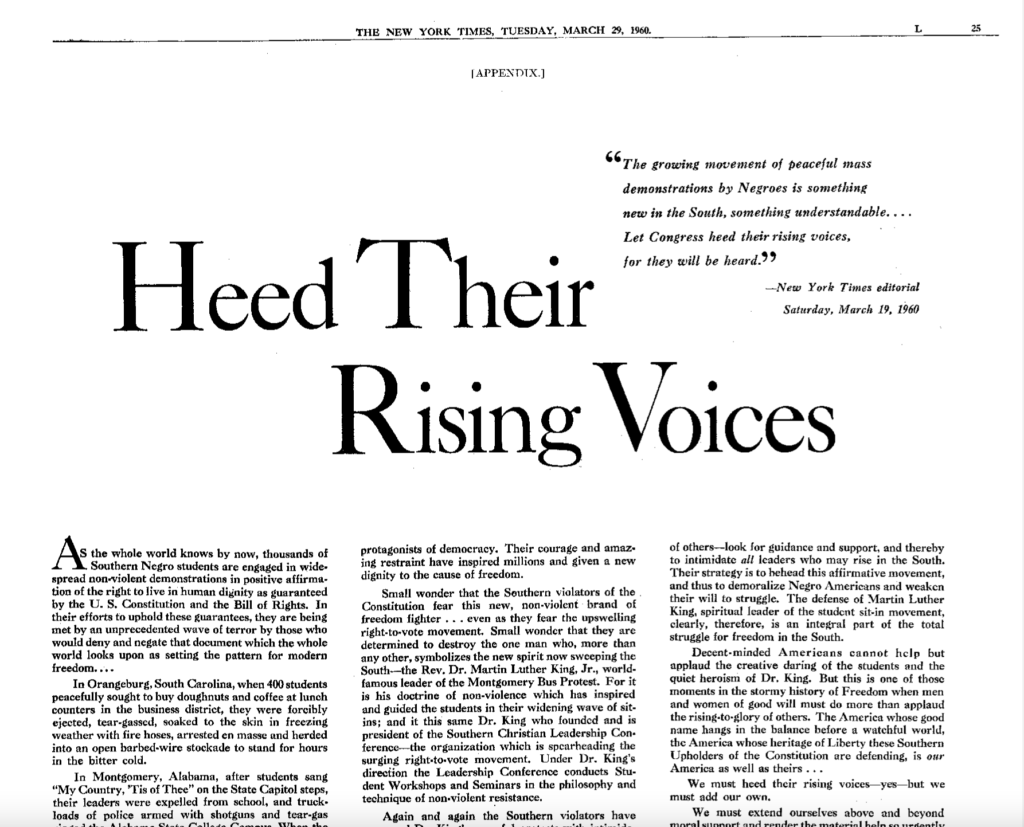

The New York Times advertisement published on March 29, 1960, that resulted in the landmark case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan in 1964.

The Supreme Court hears questions of federal law. In appealing from a lower court decision, the petitioner, the appealing party, must show that there are important issues of federal law involved and that the lower court either failed to take them into account or got them wrong. There were two possible federal questions in the Sullivan case. One was the constitutional validity of the “long-arm” statute involving Alabama’s jurisdiction over the Times. The other was whether Alabama’s libel law violated the First Amendment. If the jurisdictional question was to be the basis of review, the approach would be by appeal, since the argument would be that the application of the Alabama statutes was unconstitutional. Review would be obligatory, meaning that the Court was required to hear the case. But if the issue was the constitutionality of Alabama’s libel law, the petitioners would have to file a petition for certiorari to get the Court to hear the case. This is a request that the Court order a lower court to send up the record of the case for review. The Court received thousands of such petitions each year and granted just a handful.

Wechsler called on his junior colleague Marvin Frankel, one of his former students, to help him with the petition. Frankel, forty-two, had just been hired as a professor at Columbia. Frankel was a man of great smarts and determination. As an undergraduate at Queens College, he had driven ice cream trucks and pushed clothes racks in the garment district of Manhattan to pay for his studies. After Army service, Frankel attended law school, then worked for the solicitor general’s office in Washington, helping to write briefs and argue cases before the Supreme Court. He was a partner in the New York law firm Proskauer Rose for six years before going to teach at Columbia. Frankel idolized Wechsler. The younger man would come up with the most important ideas of the appeal, but he ceded the credit to his mentor.

Before they could write, Wechsler and Frankel had to decide an important matter. They debated whether they should emphasize the First Amendment argument or the subjection of the Times to the jurisdiction of Alabama. Wechsler concluded that the jurisdictional argument would not be a winning one and that the First Amendment point had “greater sex appeal.” The jurisdictional argument was flawed, he believed, because Judge Jones had held early on that Eric Embry made a general appearance and that the Times forfeited any right to claim that Alabama lacked personal jurisdiction over the Times. Wechsler recommended that the Times file a writ of certiorari, leading with the libel claim and making the jurisdictional claim secondary.

Wechsler told Loeb why they should emphasize the First Amendment point: the massive libel judgment inflicted on the Times for criticizing a public official—without direct reference to that official, and arguably without inflicting any damage to his reputation—was an infringement of freedom of speech and press. He told Loeb that “if we couldn’t interest the Court in a petition for a writ of certiorari on this issue, we really had to withdraw from the South in the distribution of the Times, because so long as the civil rights struggle lasted, we were going to be sitting ducks for libel actions everywhere.” But he was pessimistic about how the point could be made as a technical matter.

Wechsler could argue that the clear and present danger test should apply to defamation. Yet he found it hard to see how the formula would work, as the danger of injury to reputation would almost always be clear and present. Moreover, the doctrine was in disrepute after the way it had been used in Dennis v. U.S. to justify repression of the Communist Party leaders. The other main First Amendment test was the balancing test. But balancing was already used in libel cases under state law, and Wechsler wasn’t sure that it would be useful to try to convince the Court to rebalance the interests between free speech and reputation.

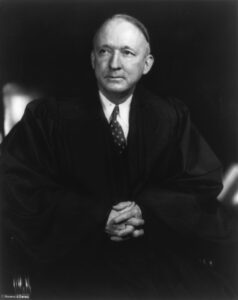

Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black in a Nov. 18, 1937 portrait. (Library of Congress/Harris & Ewing Collection)

It was Frankel who came up with a brilliant way to turn the common law of libel into a constitutional issue. “Let’s pursue a Sedition Act strategy,” he told Wechsler. Frankel wanted to shift the issue in the case from the right to protect reputation to the right to criticize the government. He believed that the Sullivan case could be recast so that it resembled not so much an ordinary libel suit as it did cases like Abrams v. United States and Whitney v. California in which the government had prosecuted speech that was critical of official policy. The seditious libel analogy had likely been inspired by Hugo Black’s comments a few months earlier. Frankel prepared a memorandum for Wechsler on how the case could be “played up with the seditious libel angle.”

Wechsler would argue that a massive damage award levied for criticizing an officer of government for his official conduct was akin to the crime of seditious libel, long assumed to be unconstitutional. As a technical matter, an action for civil libel and the crime of seditious libel are different: civil libel involves money damages for injury to individual reputation, while seditious libel involved criminal punishment for an attack on the government or its officials. Wechsler would claim, nevertheless, that permitting Sullivan to recover on the theory that he was defamed by criticism of the “police” in Montgomery constituted liability for criticizing government. Wechsler would attempt to convince the Court that in hearing the case and granting protection for libelous statements about public officials, they were following existing constitutional tradition and not doing anything revolutionary at all.

Tags