On October 30, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey announced that his company would no longer accept political advertising on its platform. As the tech company prepares to implement the new policy on November 15, people have begun to raise questions about what such a policy would look like.

“We’ve made the decision to stop all political advertising on Twitter globally,” Dorsey said in a eleven-part Twitter thread that afternoon. “A political message earns reach when people decide to follow an account or retweet. Paying for reach removes that decision, forcing highly optimized and targeted political messages on people.”

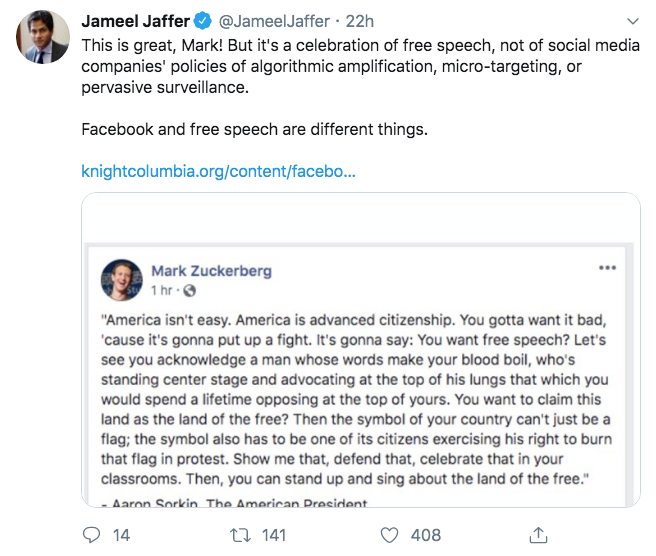

Twitter’s decision contrasts sharply (and purposefully) with that of Facebook, whose CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, recently delivered a highly-broadcasted speech defending the company’s policy to exempt politicians from their fact-checking program. In his speech, Zuckerberg likened fact-checking political advertisements to excessive speech regulation, and insisted that it was unwise for tech companies to moderate political speech.

“Banning political ads favors incumbents and whoever the media covers,” Zuckerberg argued. “Even if we wanted to ban political ads, it’s not clear where we’d draw the line…Would we ban all ads about healthcare or immigration or women’s empowerment?”

See also: Zuckerberg Defends Facebook’s Policies in Speech at Georgetown University

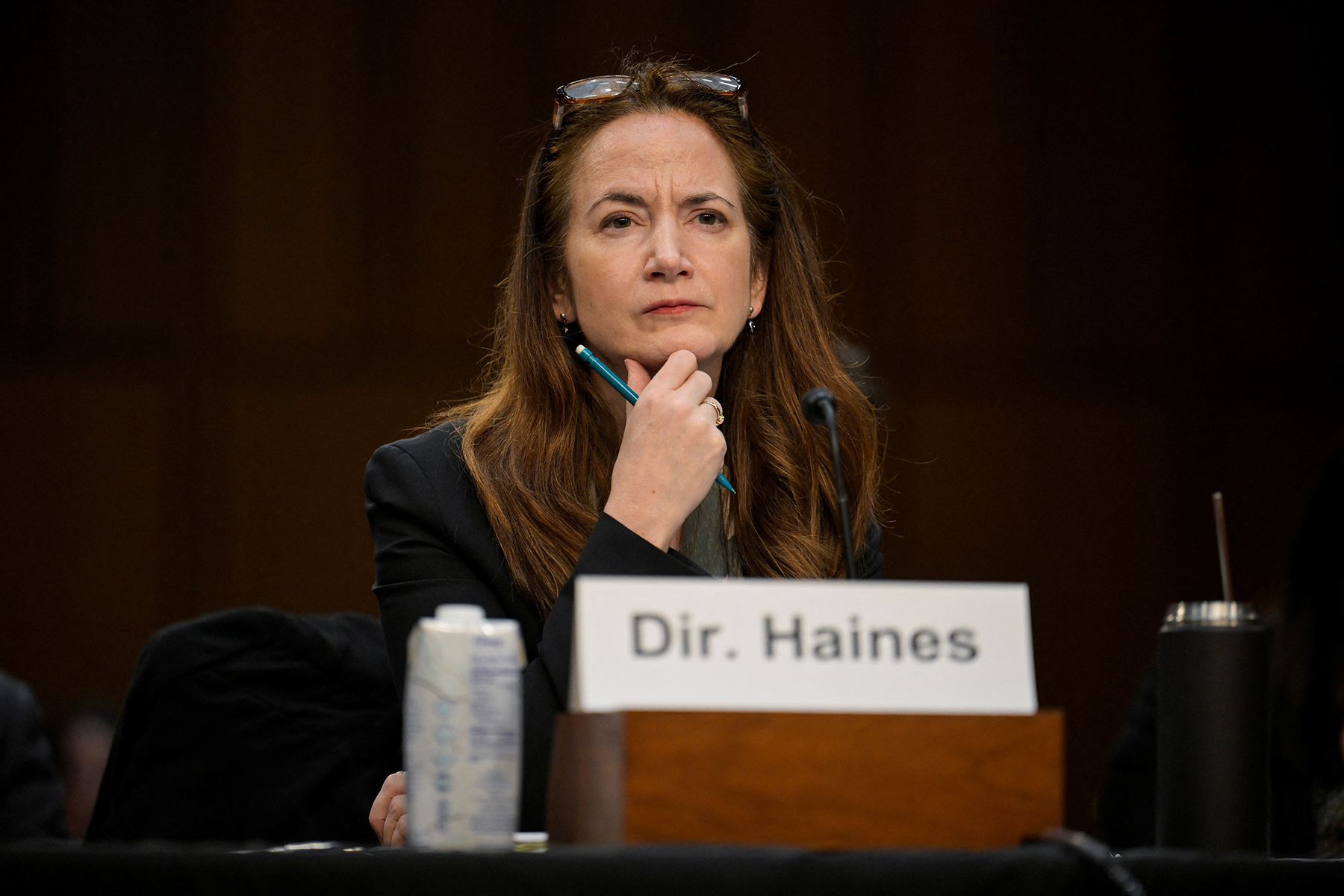

Zuckerberg’s defense of unchecked political advertisements was met with hefty criticism. The vice president of Color of Change, a racial justice organization, told The Washington Post “the only principle” reflected in Facebook’s decision “is business as usual and trying to line their pockets.” Jameel Jaffer, Director of Knight First Amendment Institute, said Zuckerberg was conflating unregulated social media with healthy public discourse. And the president and chief executive officer of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights Vanita Gupta argued that the company’s policy would imperil elections.

While notably more positive than Zuckerberg’s reception, Dorsey’s reception wasn’t universally warm. PEN America, a human rights group that advocates for free expression, “cautiously welcome[d]” Twitter’s ad policy, it said in a statement. While PEN applauded the company’s “willingness to put responsibility above revenue,” it also recognized potential consequences such as “advancing incumbents who rely less on ads.”

Will Oremus, a senior writer for Slate and OneZero was even less optimistic, writing that “banning political ads is not as straightforward, nor as obviously correct” as Dorsey’s fans seemed to think.

For Oremus, both Facebook and Twitter’s policies are problematic in that neither takes on the editorial challenge of tackling misinformation. So while Facebook’s policy allows for the circulation of falsehoods and hate speech, Twitter risks negatively impacting activists, labor groups, and organizers who rely on advertisements to advocate for their causes.

“Big tech platforms have taken over many of the roles of the traditional media in a democratic society, and sucked up most of the profits. But they remain loath, for understandable reasons, to take on the laborious editorial responsibilities of sifting truth from falsehood, and legitimate arguments from bigotry or propaganda,” Oremus wrote.

The Washington Post OneZero The Verge

Tags