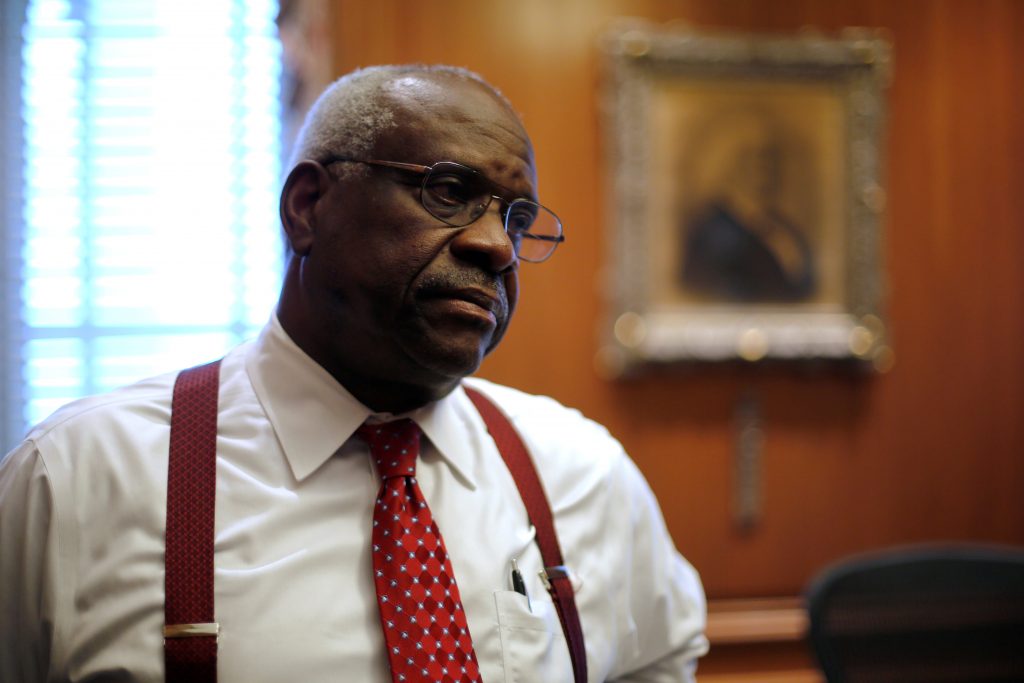

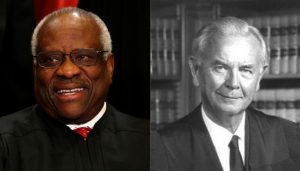

Justice Clarence Thomas (L), who wrote a concurring opinion in McKee v. Cosby REUTERS and Justice William Brennan (R), who wrote for the majority in Times v. Sullivan.

See here for more on New York Times vs. Sullivan.

Read “Dubious Doubts and ‘the Central Meaning of the First Amendment’—A Preliminary Reply to Justice Thomas” by Lee Levine and Stephen Wermiel. (This essay is being posted simultaneously on First Amendment News.)

Read “Fear Not: New York Times v. Sullivan Heartily Embraced by the Court’s Newest Jurist, Justice Kavanaugh” by Laura Handman & Lisa Zycherman (This essay is being posted simultaneously on First Amendment News.)

News & Analysis

February 19, 2019: Calling for the reconsideration of the actual malice standard is a major attack on New York Times v. Sullivan

Justice Clarence Thomas called on the Supreme Court to reconsider a landmark ruling that made it difficult for public officials to prevail in libel suits.

The Court had been considering whether to take up a case involving a woman who had accused Bill Cosby’s lawyer of defaming her. That came after she had accused Cosby of sexual misconduct in 2014. In his concurring opinion to deny certiorari, Thomas took aim at the 1964 ruling in Times v. Sullivan. “The New York Times and the Court’s decisions extending it were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law,” wrote Thomas.

In New York Times v. Sullivan, a police commissioner in Alabama filed suit alleging that he’d been libeled by an ad that ran in the Times, published on March 29, 1960 involving a civil rights incident in Montgomery, Alabama.

The Court’s ruling brought First Amendment limitations on libel claims for the first time, making it extremely difficult for public officials to win such cases.

The Supreme Court ruled that in order to support a claim of libel, the First Amendment requires a public official to prove what the Court called “actual malice”—that the defendant published with knowledge that the statement was false or with reckless disregard for the truth. In two cases decided three years later (1967), Associated Press v. Walker and Curtis Publishing Company v. Butts, the Court extended the Times ruling to also require public figures to prove intentional or reckless falsehood. Finally, the Court in 1974 in Gertz v. Welch created another category, limited-purpose public figures, who were not well known but voluntarily entered a public controversy with the intent to influence the outcome. Limited public figures, too, would have to prove intentional or reckless falsehood.

Thomas criticized the Sullivan ruling, writing, “From the founding of the Nation until 1964, defamation law was ‘almost exclusively the business of state courts and legislatures’,” and as a result, he contended that federal courts have undermined states’ ability to legislate these types of cases.

Thomas isn’t the only Justice to criticize the landmark ruling. Former Justice Antonin Scalia was a vocal critic, and in 2012 interview on “Charlie Rose,” Scalia said that he “abhors” the ruling, according to the Washington Post.

CNN Above The Law USA TodayDocuments & Resources

Concurring OpinionTags