Staff writer Soraya Ferdman talks with University of Utah law professor RonNell Andersen Jones about Neil Gorsuch’s recent dissent in Berisha v. Lawson, and the arguments he lays out for why the court should reconsider the actual malice standard established in New York Times v. Sullivan. Widely considered the most important First Amendment decision of the 20th century, Sullivan has recently become the target of big-name critics including Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and D.C. Circuit Court Judge Laurence Silberman, who argue that the legal standard allows too much room for defamation.

During his confirmation hearings, Gorsuch originally told Congress that he believed Sullivan was settled doctrine, the Justice now says that changes in the media landscape have raised difficult questions.

Ferdman spoke with Andersen Jones about his dissent. Andersen Jones shares many of Gorsuch’s anxieties about the spread of disinformation and the ease with which people can use social media to harm others’ reputations. However, she does not think that changing defamation law would solve these problems. Instead, she argues that loosening defamation standards would make it harder for good faith journalists to do their job.

Professor RonNell Andersen Jones is an Affiliated Fellow at Yale Law School’s Information Society Project and the Lee E. Teitelbaum Endowed Chair and Professor of Law at the University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law. She researches legal issues affecting the press and the intersection between media and the courts. Her scholarship addresses press access and transparency, the role of the press as a check on government, newsgathering rights, reporter’s privilege, and emerging areas of social media law. Her scholarly work has appeared in numerous books and journals, including Northwestern Law Review, Michigan Law Review, UCLA Law Review, Minnesota Law Review, and the Harvard Law Review Forum.

Soraya Ferdman: In his recent dissent in Berisha v. Lawson (2021), Justice Neil Gorsuch argues that today’s media landscape looks very different than it did when Sullivan was decided. He writes that technological changes have wiped out many print newspapers, and replaced them with “the rise of 24-hour cable news and online media platforms that ‘monetize anything that garners clicks’.” Do you agree with his description of the current media landscape?

RonNell Andersen Jones: It’s unquestionably true that the media and news landscape have changed dramatically since Sullivan was decided almost six decades ago. But one important thing to recognize is that Sullivan isn’t just about protecting a free press–although it certainly is that–it is also central to the operation of American discourse more broadly. It protects the citizen’s right to have robust conversations about elected officials and other powerful people without fear of crushing damages. To the extent that the constitutional standard in Sullivan should be reconsidered because the media landscape has changed, that blinks a bit at the facts of Sullivan itself. The case arose out of an advertisement placed by citizen critics, not a news article.

To be sure, Sullivan was a moment when the Court praised and celebrated the press function, and we could structure the doctrine around special rights for those engaging in the press function. But the court pretty early on determined that that isn’t the route it would take, and said that these protections applied no matter who was engaging in that speech on matters of public concern. The Sullivan doctrine focuses on who we are talking about and whether that entity is a public official or public figure, not on who is doing the talking and whether that entity is the press.

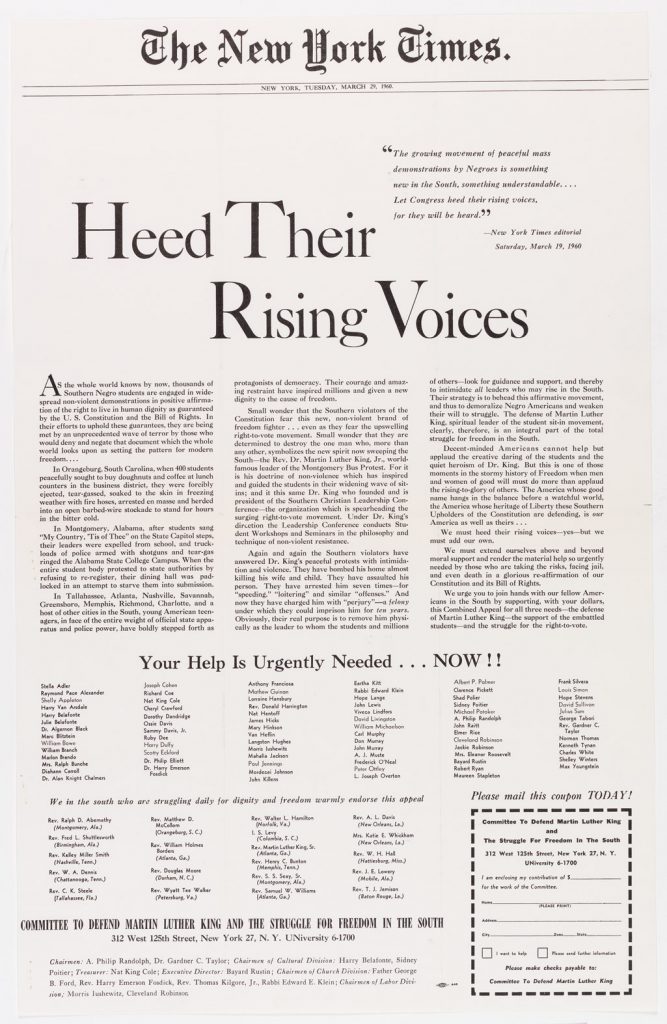

During the Civil Rights movement, The New York Times published an ad requesting donations for Martin Luther King, Jr. The ad, pictured above, contained several minor factual inaccuracies. In a unanimous decision in New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), the court sided with the newspaper, writing that “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate, and that it must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the ‘breathing space’ that they ‘need . . . to survive.’”

SF: Do you agree with any of the remedies he proposes?

RAJ: Part of the difficulty in answering this question is that Justice Gorsuch’s dissent actually goes out of its way not to propose specific doctrinal remedies in this area. Instead, it structures itself as a set of unanswered inquiries about how the changing nature of the media and the changing nature of defamatory falsehoods might warrant the Court taking another look at one or more aspects of the Sullivan doctrine. By my reading, Justice Gorsuch seems to have some concern that the news media either is not serving the public’s need for truthful information as well as it once did, or that something about the structure of the Sullivan standard might motivate the press to behave in ways that are different than the Court imagined at the time the doctrine was established. I think there are good arguments to be made that newsgathering and the distribution of trustworthy information on matters of public concern are suffering today—although perhaps for reasons more complicated than the ones that Justice Gorsuch identifies. The economic and structural difficulties faced by many news organizations—particularly local news organizations—are pretty staggering at the moment. What I hope we will be able to do in this space is consider the wider set of problems and solutions for protecting a vibrant ongoing press function in this country.

SF: There has always been anxiety about false information in free societies. What the court decided in Sullivan was not that there were no bad-faith actors in journalism, but that the laws at the time made it too easy for public officials to intimidate good faith journalists and chill speech especially on important matters of public affairs. Social media has made it far easier for purveyors of disinformation to obtain a platform. What Gorsuch seems to be saying is that the calculation, when applied to today’s media environment, might allow for too many bad actors to get away with legitimate defamation. Do you agree?

RAJ: Justice Gorsuch is tapping into some themes that scholars in this area have been lamenting for a while now: the ease with which misinformation and disinformation can spread and the harm to individuals and democracy that can come from these new cheap, speedy, efficient, distributors of lies. And we absolutely have to tackle these threats. The hard question here is going to be whether adjustments to the Sullivan doctrine are the right route for doing so.

SF: Is there a way to tweak the defamation standard without sacrificing protections for good actors?

RAJ: There are lots of reasons to think that defamation law is a sloppy tool for the disinformation problem. Anonymous online posters of information are often just outside the reach of a libel suit. They are not entities that are sued for defamation because they’re hard to find and hard to sue. They are often not worth suing because their expression is so extreme that it might be found to be hyperbole, or because no single individual who spread it had enough of an impact or enough assets to be worth going after in a long, tedious, time-intensive tort suit.

The press, in contrast, have deeper pockets and therefore a target on their backs for the kind of legal intimidation situation that Sullivan addresses. They also have libel insurance policies that individual random distributors of online disinformation do not. In other words, it might be that the online disseminators of disinformation just aren’t as likely to be the defendants of libel actions in any event. We’re barking up the wrong tree.

To be sure these sweeping harmful lies that spread on social media are incredibly problematic and harmful. My massive worry here is that reconsidering Sullivan will create a vulnerability for those entities that are attempting to maintain some reputation for newsgathering with no real payoff in tackling the wider societal problem that is driving that reconsideration.

“Anonymous online posters of information are often just outside the reach of a libel suit…. They are often not worth suing because their expression is so extreme that it might be found to be hyperbole, or because no single individual who spread it had enough of an impact or enough assets to be worth going after in a long, tedious, time-intensive tort suit. The press, in contrast, have deeper pockets and therefore a target on their backs for the kind of legal intimidation situation that Sullivan addresses.”

SF: Gorsuch writes that the definition of actual malice has evolved from “a high bar of recovery into an effective immunity,” and that people today are incentivized to avoid investigation so that they can essentially plead ignorance should they be used for defamation. Is that a valid concern?

RAJ: We unquestionably want our First Amendment standards to create the right kinds of incentives—promoting as much free speech as possible and as much accurate, truthful speech as possible. I do think there is a really fruitful conversation happening amongst scholars in this area right now about how the doctrine could best strike the balance and reward those who make some effort to get it right, as opposed to those who take no steps to do so. That said, I spend a lot of time studying media organizations, publishers, and other major participants in conversations on matters of public concern in America, and I can say with some certainty that major newsgatherers are not actively avoiding investigation in an effort to dodge any subjective awareness of falsity. On the contrary, the sets of incentives that motivate their work—from a variety of directions—push them to want to be well-sourced, accurate, and accountable to their audiences.

We might note that the incentives and motivations in the opposite direction are the major concerns the Court was trying to address in the Sullivan line of cases. If defamation law creates a weapon that can be wielded against a speaker in ways that are financially debilitating, it creates what the Sullivan Court called a “pall of fear and timidity upon those who would give voice to public criticism.” The Court worried that provable truth is too great a burden to put on those speakers because some falsity is inevitable in free debate—and we don’t want to incentivize people to self-censor rather than contribute to that debate. Striking the right balance on this question is hard, but it’s important to free speech and important to democracy more broadly.

SF: There is another part of the Sullivan progeny that Gorsuch seems to have trouble with. He writes social media has made the limited public figure category “extremely malleable and even archaic.” When the court extended the actual malice standard to public figures in Curtis Publishing v. Butts (1967), they did so based on the reasoning that many famous public figures are as influential as public officials in the affairs of our country, but they are not subject to the electoral process. It’s important for people to follow what these public figures are doing and so journalists need a higher level of protection from defamation lawsuits when they discuss their activities. In Gertz v. Robert Welch (1974), the court again extended the standard to apply to individuals who were not widely known but had voluntarily entered a public controversy in their community. Now, we have people writing blogs and engaging in Twitter discussions. Are these people now considered public figures?

RAJ: This does seem to be another issue of concern for Justice Gorsuch–that more people are potentially public figures today because the notions of virality and fame are slipperier in the current media environment than they once were.

The underlying public figure doctrine here really has two parts to it. The first is a notion of access that public figures like public officials usually enjoy significantly greater access to effective modes of counter speech. And because of this, they can answer and correct a falsehood with their own truthful speech in the marketplace of ideas. The second is a notion of voluntary exposure that public figures like public officials have made some choice to thrust themselves into the limelight, and have made the decision to voluntarily expose themselves to the risks that come with that, including the risk of injury from defamatory falsehood, either for all purposes or for a particular public controversy where they’ve gotten involved and tried to influence public issues.

SF: RonNell, this can get complicated. How would you determine public figure status, for example, for someone who writes a blog or who has a large Twitter following? For example, how many followers should a person have before they are clearly a limited purpose public figure?

RAJ: Yes, it is definitely a more complicated space than it once was, because the ways we can become known to others and the ways we can insert ourselves as a prominent participant in a conversation on a matter of public concern are more varied than they once were. The lower courts have done a lot of hard work on some of these fronts, exploring the ways that the old doctrine maps onto the new realities. But I think there are many folks who work in this area who think this is the question that is most likely to attract more attention from the Supreme Court. Justice Gorsuch’s opinion highlights some of the major arguments we’ve seen swirling around in this area—for example, the assertion that the public figure doctrine now casts too wide a net to include those who became well known because they were victims or were only prominent in some relatively obscure online space.

He cites, for example, a case where someone was deemed to be a limited purpose public figure because they were involved in conversations on a jet ski website. Interestingly, though, the case that Justice Gorsuch was urging the Court to take to reconsider Sullivan didn’t involve any of these complexities. The plaintiff in Berisha was the son of the then-Prime Minister of Albania, who by his own admission had 100 percent name recognition in his country and had been on the front pages of many major American newspapers, receiving massive press attention related to arms dealing and allegations of corruption. This wasn’t, in other words, one of those people who became famous for having a lot of Twitter followers or for simply defending themselves, or any of those other complexities that are being suggested as the new and difficult issues in this area. The fact that Justice Gorsuch was prepared to take this case might suggest he’s thinking more broadly about the reconsideration of the Sullivan doctrine, and not just about the need to offer useful clarification about how the new media landscape creates tricky dynamics in the public figure realm.

“[O]ne important thing to recognize is that Sullivan isn’t just about protecting a free press…It protects the citizen’s right to have robust conversations about elected officials and other powerful people without fear of crushing damages.”

SF: For decades, the Supreme Court saw the press as playing a key role in maintaining a healthy democracy. But in recent years, the Court’s opinion of the press has shifted. You recently published a study about this shift with University of Georgia law professor Sonja West. What did you learn from the study? Did it give you some clues as to what caused this shift?

RAJ: Our study shows unquestionably that this shift is happening: the Supreme Court’s tone and characterization of the press over time has declined dramatically. The current Court, in particular, seems to have soured on the press and be disinclined to recognize freedom of the press. It no longer speaks of the press in ways that highlight its role in democracy, its contributions to society, or in ways that emphasize its trustworthiness, accuracy, or ethics.

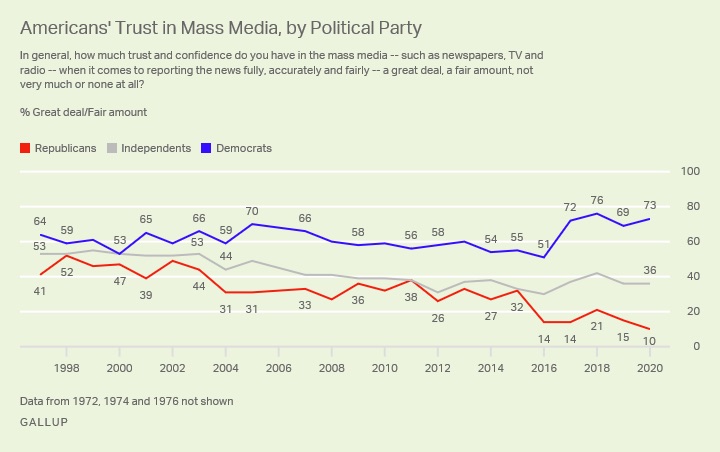

Why this is happening is much harder and much more difficult to capture as an empirical matter because there are so many moving parts. Public opinion polls show us that the citizens’ views of the press have also precipitously declined in the same time period, especially in some ideologically specific groups. The changing nature of media behavior, the changing contours of the media ecosystem, the increased partisanship of the press, and the populist movement to discredit knowledge institutions more broadly, may all be playing into this decline. Whatever the cause, the data is quite clear that the Justices of the Court simply do not speak of the press or the press function in the positive ways that they did even a generation ago.

2020 Gallup poll on American’s trust in mass media.

SF: When Clarence Thomas published his concurring opinion in Mckee v Cosby (2019), where he argued that the court should reconsider the actual malice standard established in New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), many people viewed his opinion as that of an outlier. Since then, other conservative judges, including Fourth Circuit Judge Laurence Silberman and now Gorsuch, say that they are also rethinking this landmark decision. Do you think we could see a weakening of this standard in our lifetime?

RAJ: I think most court watchers would have to agree that the odds of Sullivan being reconsidered are higher today than they were a month ago. It is actually a development that has happened with remarkable speed since 2016. Then-candidate Trump made what was at the time thought to be the deeply improbable suggestion that we should reconsider Sullivan and open up libel law to make it easier for public officials like him to sue the press for defamation. Then, in 2019, when Justice Thomas advanced this idea for the first time at the Supreme court, his comments too, weren’t taken particularly seriously as a threat that the long-standing precedent would be abandoned in part because he’s somewhat idiosyncratic in his originalist First Amendment views on the subject.

But there have been, as you note others, who have now embraced the idea. The latest from Justice Gorsuch is notable because he is arguing that Sullivan should be reconsidered because it no longer makes sense in our new communications and media landscape, which is a signal that the questioning of Sullivan isn’t limited to that idiosyncratic originalist position that Justice Thomas holds but may instead be broader. Justice Gorsuch was squarely asked about Sullivan in his 2017 confirmation proceedings and seemed to view it as settled doctrine that he would respect and apply. So the fact that he is now urging a rethinking of it may suggest there are some changing tides.

The question is: where are the other seven Justices on this? The other Justices of the court were free to join Thomas and Gorsuch in voting to hear the case that was seeking review this past term and decided not to do so. But this could be for a variety of reasons—maybe they want to keep Sullivan as is, or maybe they believe it’s important for the Court’s institutional reputation that it not disrupt settled precedent. Or maybe they are planning to disrupt settled precedent in other areas in the coming term and wanted to hold back here. Or maybe they really do want to tinker with Sullivan, but thought this case wasn’t a good vehicle for doing so.

First Amendment law is a space where dissenting views have in some instances migrated into majority positions. For now, all we know for certain is that Justice Thomas would overturn Sullivan in its entirety and that Justice Gorsuch would like to take a case to reconsider the way Sullivan operates in the differentt media ecosystem.

Beyond that, we will have to wait and see.