By Professor Stephen D. Solomon, Editor, First Amendment Watch

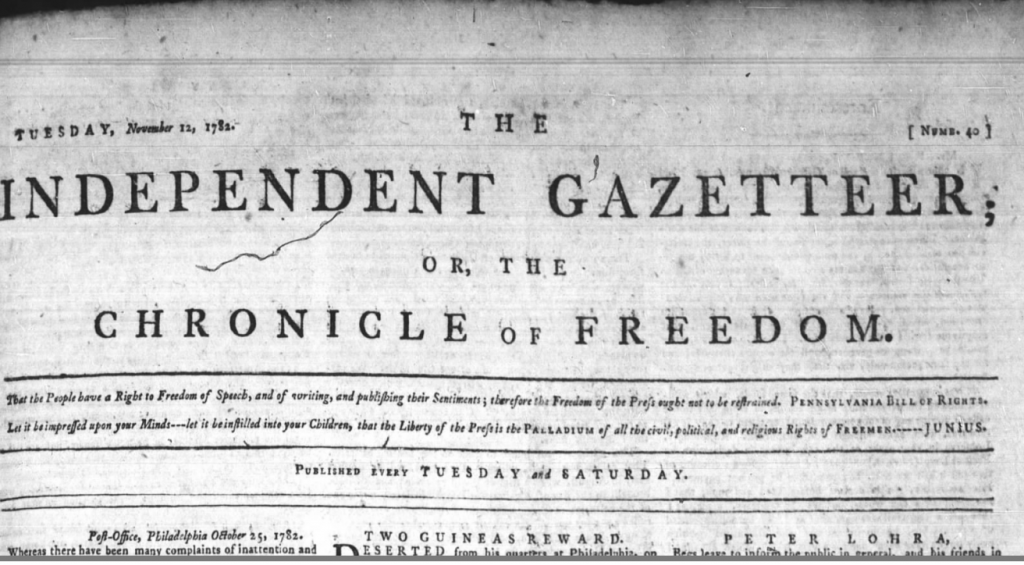

A writer who took the name Junius Wilkes made a critical contribution to the discussion of press freedom even as the Revolutionary War neared conclusion.

Writing in The Independent Gazetteer (Philadelphia) in 1782, Wilkes said that citizens are sovereign and therefore powerful, and “should have a right to examine and lay before the world such proceedings of power, as appear to him exceptionable and alarming.” Public officials are “merely public servants and stewards, and, as such, accountable at all times to the people.” They take the risk of criticism in assuming office, and their remedy should be through the press and not prosecutions.

Wilkes argued that the press should be protected for criticisms of government officials “when they even appear false and groundless.” He continued, “We are not to expect perfection in this life, where the best of things are daily liable to injury and abuse.” If writers and printers are subject to libel prosecutions, press freedom is “annihilated and ruined.”

Press freedom, said Wilkes, was critical to separation from England. “Noting but opinions circulated through the medium of a paper produced the American struggle for liberty, and gave birth to our glorious independence!”

Junius Wilkes (Excerpt The Independent Gazetteer (Philadelphia), 9 November 1782)

“Upon an examination of public and general subjects affecting society, and the regular conduct of men in office and power, the glory and happiness, the misery or wretchedness of a state doth depend. As every person is deeply interested in that point, and may probably suffer in common with others, from an inversion and abuse of public duty, it seems quite reasonable and necessary, that each citizen should have a right to examine and lay before the world such proceedings of power, as appear to him exceptionable and alarming. . . .

No character is more dignified than that of a free citizen: It implies ever thing. All power is derived from him, which he directs and controuls. He feels, and is convinced of, his sovereignty and importance. Public officers are merely public servants and stewards, and, as such, accountable at all times to the people. . . .

Shall it then be deemed libellous and criminal for a member of a free country, publicly to assert his birthright? Reason rouses with indignation, at the bare idea; and the genius of freedom cannot shelter the absurdity! Do the community receive no benefit from the free investigation of public affairs? Are not such opinions of individuals often interesting? Nothing but opinions circulated through the medium of a paper produced the American struggle for liberty, and gave birth to our glorious independence! Had those illustrious worthies who maintained our cause been intimidated from publishing their sentiments under an idea of ‘transgressing the law,’ and involving the Printer with prosecutions as a libeller, there is no doubt we should have sunken to the lowest class of slaves. Injured as we were, there could be no redress. Submit or perish must have been the sanguinary decree. . . .

If a Printer is liable to prosecution and restraint, for publishing pieces on public measures, conceived libellous, the liberty of the press is annihilated and ruined. ‘A privilege invaded and superseded, is no privilege at all.’ The danger is precisely the same to liberty, in punishing a person after the performance appears as to the world, as in preventing its publication in the first instance. The doctrine of libels, is of pernicious consequence to the freedom of the press. For though the law is settled in its idea of a libel, yet it is left to the arbitrary construction of the Judges, to determine the point from the circumstances of the case. . . .

On the whole, it is abundantly evident, the constitution will justify those publications which respect the conduct of public servants; and, when they even appear false and groundless, it is rather an inconvenience upon the occasion, a kind of damnum absque injuria. We are not to expect perfection in this life, where the best of things are daily liable to injury and abuse; and along with the liberty of the press, it is not wonderful if there should happen occasionally an unseemly . . .

Besides public officers are acquainted with the difficulties of their place, on accepting the post, and they certainly accept it, subject to its disadvantages, and should not therefore murmur or complain. If they suffer by defamatory accusations, the press which impeaches, is equally open to acquit,—like the spear of Telephus, the same weapon which wounds can heal. This much eventually gives greater satisfaction, and affords greater victory in favor of real innocence, than the ordinary remedies of justice.”

Tags