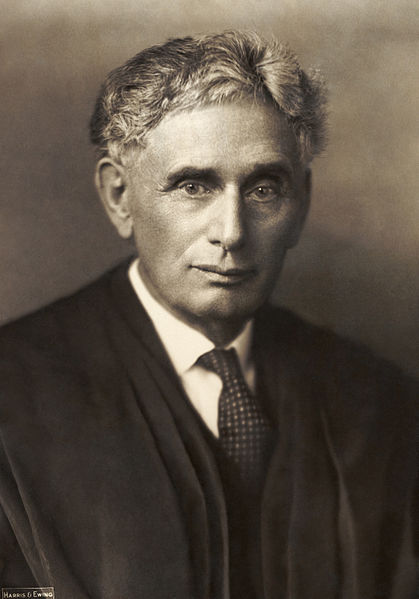

Brandeis Concurring With Holmes in Whitney v. California, 1927

Justice Louis Brandeis concurrence articulated the American idea of freedom of speech many decades before the Supreme Court began expanding the rights of expression under the First Amendment. Some of his ideas have become critical justifications for safeguarding freedom of speech even under the most challenging conditions.

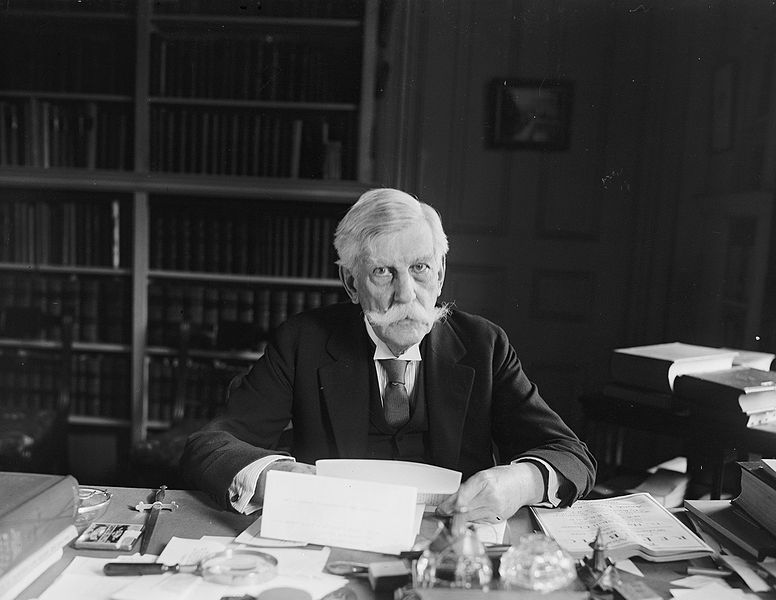

Holmes Dissenting in Abrams v. United States, 1919

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes built his support for freedom speech atop the sturdy foundation of the marketplace of ideas, supported long before by John Milton (Areopagitica) and John Stuart Mill (On Liberty). Holmes argued that “the theory of our Constitution” is that “the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas.”

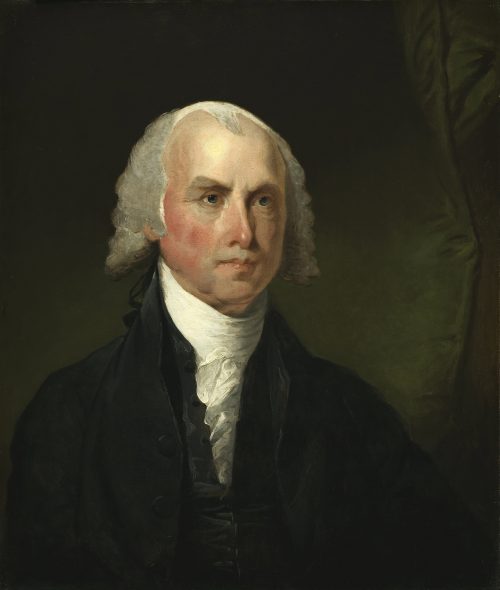

James Madison’s Report to the Virginia House of Delegates, 1800

James Madison, author of the First Amendment, wrote what is surely the most powerful defense of freedom of the press in America. He did it in protest against the Sedition Act of 1798, enacted just seven years after ratification of the First Amendment.

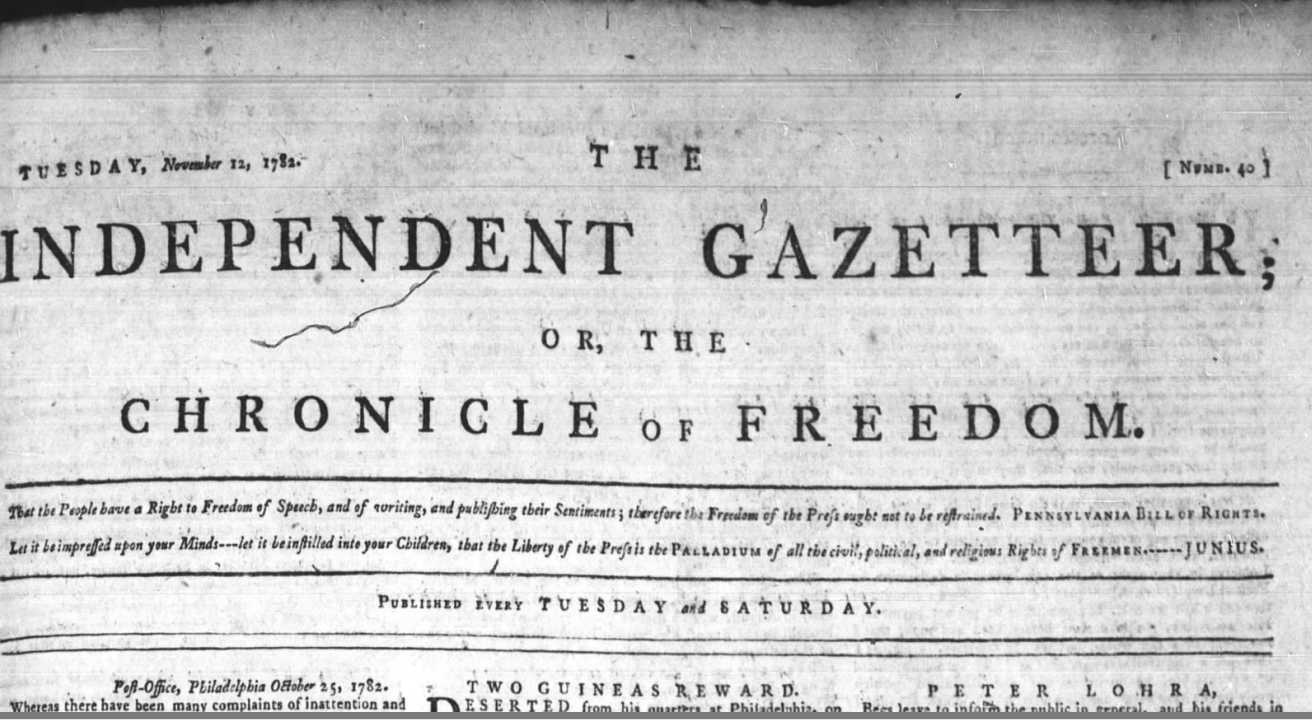

Junius Wilkes on Protections Even for “False and Groundless” Reports

A writer who took the name Junius Wilkes made a critical contribution to the discussion of press freedom in 1782. He argued that the press should be protected for criticisms of government officials “when they even appear false and groundless.”

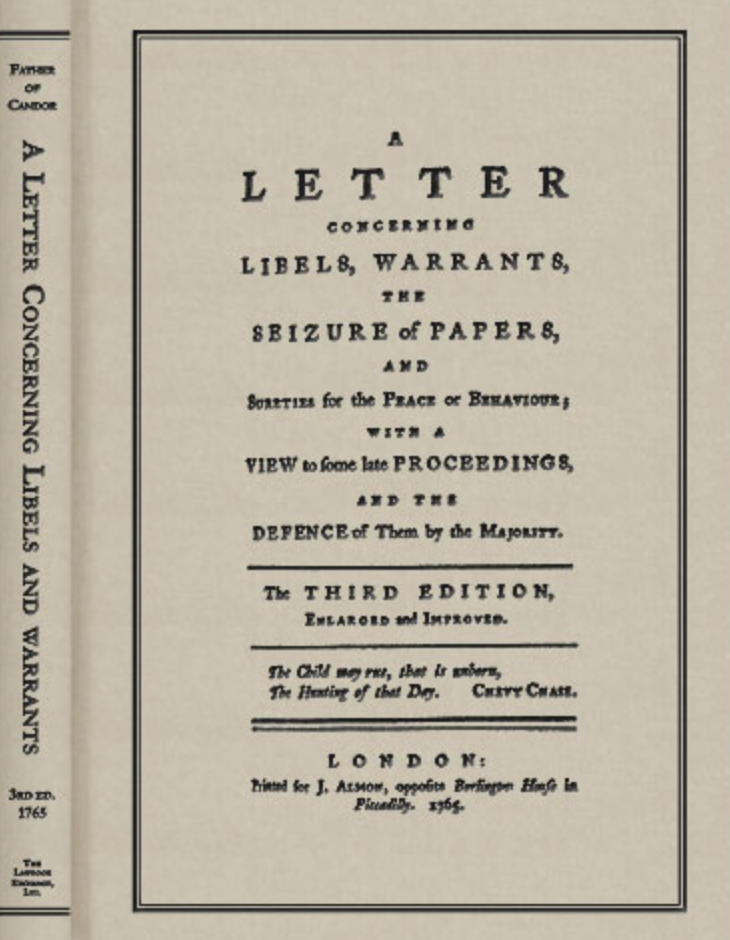

Father of Candor Anticipated New York Times v. Sullivan Over 250 Years Ago

A writer calling himself Father of Candor was far ahead of his time when he attacked seditious libel in 1764. He argued that truth should be an absolute defense against libel, and that only intentional lies should be subject to libel laws.

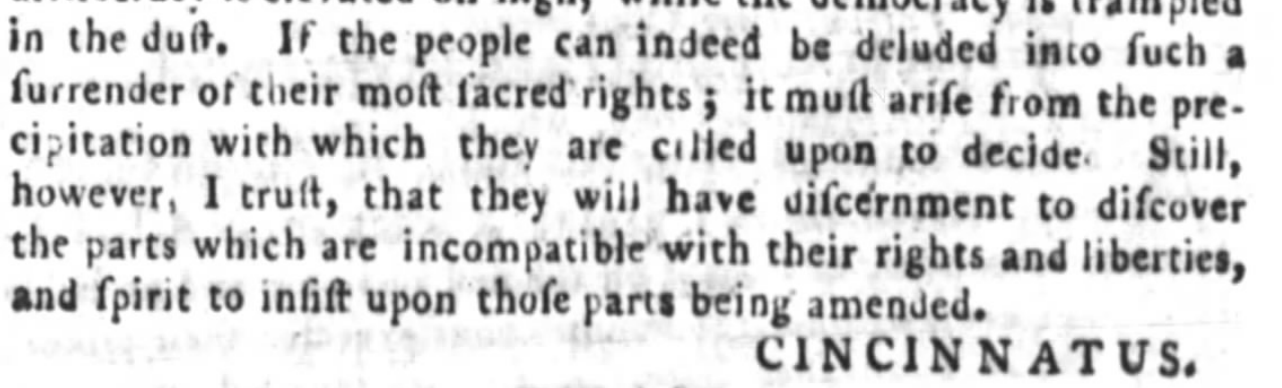

Cincinnatus to James Wilson, 1787

Why was the Bill of Rights necessary to protect freedom of the press? An 18th-century writer argues that the Constitution did not adequately ensure that the government would not try to regulate the country's newspapers.

Candid argued in 1782 for new protections for the press from seditious libel. He maintained that the press should not only examine candidates for public office, but also private characters—those “who are eligible to it, or may influence others in their choice.”

John Milton Areopagitica, 1644

Milton argued that the press should be unlicensed, advancing the classic argument that ideas should be judged in the marketplace of ideas, where the truth would emerge through “a free and open encounter.”