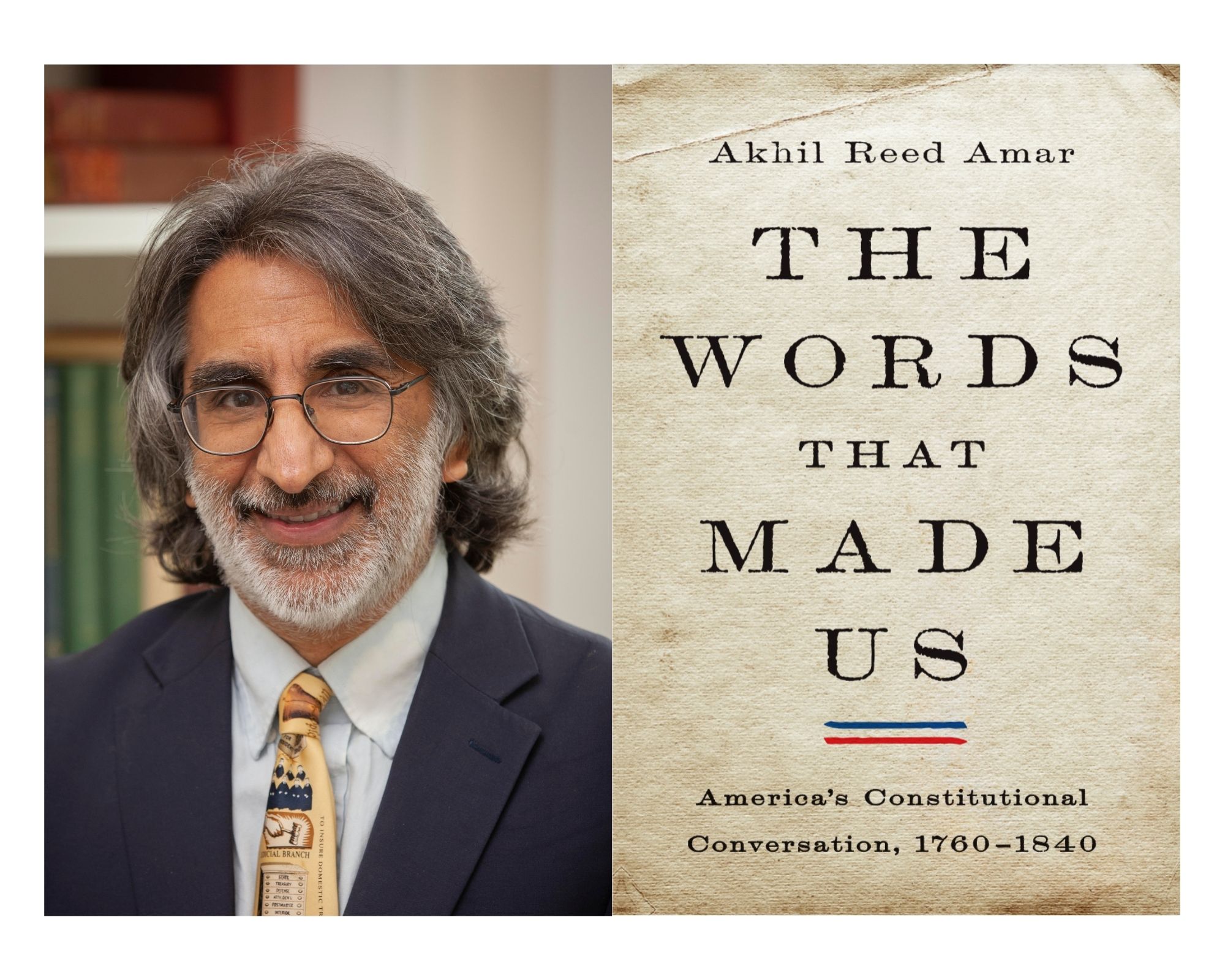

In “The Fight for Free Speech,” media lawyer and law professor Ian Rosenberg tells the story of how First Amendment law evolved in the United States. Each chapter explores a contemporary free speech question–from Colin Kaepernick taking the knee to protest police violence to Donald Trump’s legal team’s attempt to silence adult film star Stormy Daniels– and connects it to a historic court decision. The first section, excerpted here, traces our country’s protections for incendiary speech, such as calls to revolution, to a 20th-century case involving anarchists who protested the United States’ efforts to impede the Russian Revolution.

Ian Roseberg has more than 20 years of experience as a media lawyer, and has worked as legal counsel for ABC News since 2003. He graduated with distinction from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and magna cum laude from Cornell Law School. Rosenberg began his legal career clerking for a United States district court judge in the Eastern District of New York, and then working as a litigation associate at Cahill Gordon & Reindel. He is also an Emmy-nominated documentary filmmaker, and teaches media law at Brooklyn College. He lives in New York City with his wife, Caroline Laskow, and their two children.

The Women’s March and The Marketplace of Ideas

A crowd of women wearing pink “pussy hats” gather in Washington D.C. to protest the inauguration of Donald Trump on January 21, 2017. Ted Etyan via Wikimedia Commons.

A wave of pink “pussyhats” was moving from the Capitol toward the White House. Protestors were holding signs aloft as they participated in the Women’s March of 2017. “Our Rights Are Not Up for Grabs. Neither Are We.” “Our Arms Are Tired from Holding These Signs Since the 1920’s.” “My Nana Didn’t Flee Russia for This.” The crowds chanted in call and response, “Tell me what democracy looks like!” “This is what democracy looks like!”

What began as a post-election Facebook post transformed into over three million women and men demonstrating across the country and the globe at over three hundred sister events. Gloria Steinem, the feminist standard bearer and honorary chairwoman of the event, exulted to the crowds: “Thank you for understanding that sometimes we must put our bodies where our beliefs are.” Coming the day after the inauguration of President Trump, the march was also intentionally a protest of his election, offering a defiant rebuke of his nascent administration. Civil rights activist Angela Davis addressed the crowds in DC and set forth this mission in no uncertain terms: “The next 1,459 days of the Trump administration will be 1,459 days of resistance: resistance on the ground, resistance in the classrooms, resistance on the job, resistance in our art and in our music.”

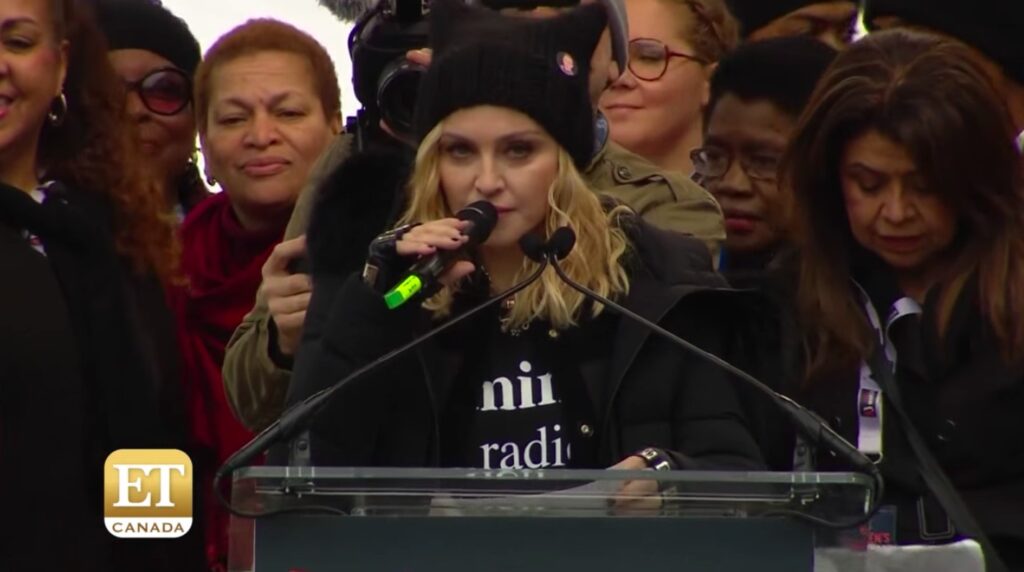

Celebrities from the art and music worlds were front and center as featured speakers. Actress America Ferrera kicked things off by telling the crowd, “It’s been a heartrending time to be both a woman and an immigrant. Our dignity, our character, our rights have all been under attack.” Scarlett Johansson wanted everyone to “get really, really personal,” and talked about visiting Planned Parenthood when she was fifteen years old, where she was treated with compassion, “no judgment,” and “gentle guidance.” Madonna caused controversy in some circles, as usual, in her speech that day. With her trademark mix of candor and provocation, she revealed, “Yes, I’m angry. Yes, I am outraged. Yes, I have thought an awful lot about blowing up the White House.” However, in her next breath she clearly rejected this notion, “But I know that this won’t change anything. We cannot fall into despair. We must love one another or die. I choose love.” The New York Times reported that the Secret Service had no comment on her statement, adding, “though an investigation seemed unlikely.” On Fox & Friends, former House speaker and Republican pundit Newt Gingrich would later say that Madonna “ought to be arrested.”

Still from actress America Ferrera’s speech during the Women’s March on Washington. 21 January 2017. via CBS News on YouTube.

Still from Madonna’s speech during the Women’s March on Washington. 22 January 2017. via ET Canada on Youtube.

What Madonna might have been surprised to find out is that a hundred short years ago she most likely would not only have been arrested for her speech, but would have been sentenced to years of jail time. She, and all the marchers, owe their First Amendment protections to one tenacious young immigrant who set in motion the events that forever changed our relationship to free speech.

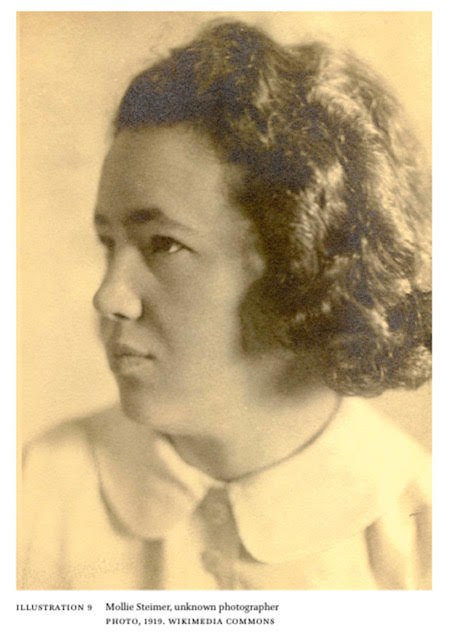

In 1913, Mollie Steimer arrived at Ellis Island at the age of sixteen. Her family was fleeing Russia’s virulent anti-Semitic discrimination and violence, so that she and her five brothers, as her parents put it, “would be brought up in a free country.”

Standing just four foot nine inches tall, Steimer was later described by legendary anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman as “diminutive and quaint looking . . . with an iron will and a tender heart.” She worked in a ladies’ shirtwaist factory, laboring long hours to earn fifteen dollars a week to support herself and help her family. “Life was hard,” Steimer wrote. “Came home late, got up early. Things began to protest in me against a system of life where people who are hard workers have to struggle bitterly just to be able to exist.” These feelings of dissatisfaction led her to reading about anarchism, “to search for a way out.” Soon Steimer became deeply devoted to the anarchist ideals of communal property, collective action, and the abolition of government, and firmly believed that this new social order “would really make life worthwhile.”

Mollie Steimer. Unknown photographer. Photo 1918. Wikimedia Commons.

Steimer joined up with a group of fellow Russian Jewish anarchists led by Jacob Abrams, a short man with dark eyes, long brown hair, and a thin mustache. Abrams worked as a bookbinder and union leader, and Steimer said his “energetic personality . . . won my admiration immediately.” Abrams and Steimer, along with their working-class compatriots—the equally “tough and fanatical” Jacob Schwartz, Hyman Lachowsky (both bookbinders), and Samuel Lipman (a furrier)—regularly met clandestinely at an apartment in East Harlem. Together this group published an anarchist journal in Yiddish, first called Der Shturm (The Storm) and later renamed Frayhayt (Freedom).

In August 1918, Steimer and her fellow anarchists were incensed by the news of a new mission launched as part of the United States’ continuing involvement in World War I. President Woodrow Wilson had just announced that he would be sending American troops to Russia. The decision was supposedly made to support Czechoslovak allies in the continuing fight against Germany. However, many viewed the action as little more than a thinly disguised effort to help the “White” Russians and attack the “Red” Bolsheviks during their civil war. Steimer saw it as an indefensible attempt to subvert the Russian Revolution, which she wrote would “lead to . . . the freeing of mankind.”

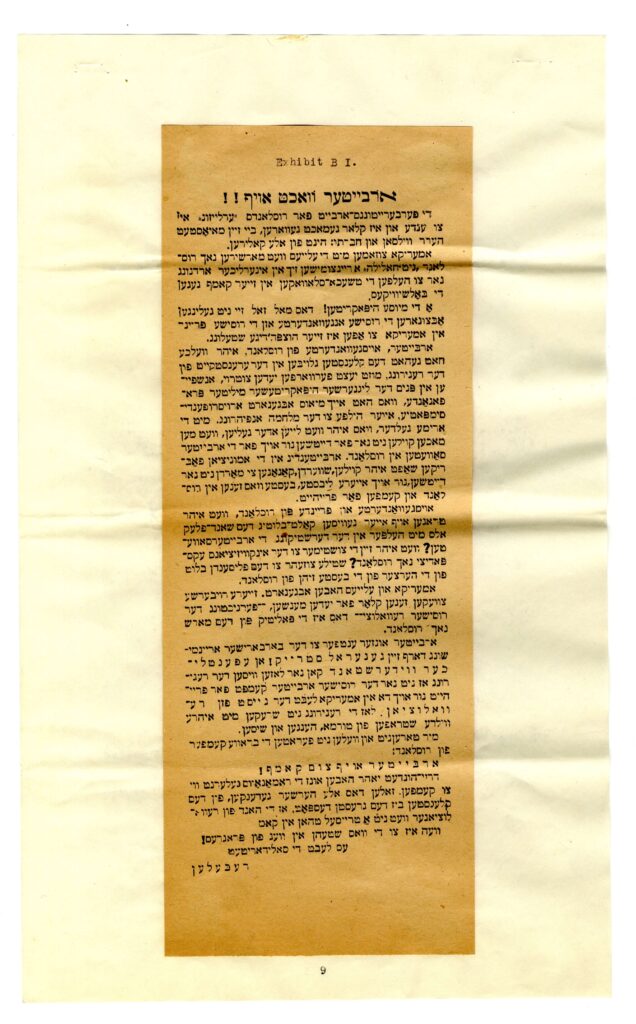

The group decided to produce two leaflets furiously denouncing Wilson and his Russian endeavor. Lipman wrote one in English and Schwartz one in Yiddish, each approximately four hundred words. In their rented basement storefront on a newly purchased press they quickly printed five thousand copies of each, on thin four-by-twelve-inch pieces of paper.

The English-language leaflet was titled “The Hypocrisy of the United States and Her Allies.” It condemned Wilson and attacked his “shameful, cowardly silence about the intervention in Russia [which] reveals the hypocrisy of the plutocratic gang in Washington and vicinity.” The document goes on to lambaste the president as “too much of a coward to come out openly and say: ‘We capitalistic nations cannot afford to have a proletarian republic in Russia.’” It ends with a plea:

Will you allow the Russian Revolution to be crushed? You: Yes, we mean you the people of America! . . . The Russian Revolution cries: “ Workers of the world! Awake! Rise! Put down your enemy and mine! Yes friends, there is only one enemy of the workers of the world and that is Capitalism. Awake! Awake, You Workers of the World!

It was signed simply: “Revolutionists.” It also has a clarifying “P.S.” that adds, “It is absurd to call us pro-German. We hate and despise German militarism more than do your hypocritical tyrants.”

The second leaflet, in Yiddish, titled “Workers—Wake Up!!,” addressed the same concerns, but in a more anguished tone and with a much more particular audience in mind. Pointedly addressing “[w]orkers in the ammunition factories,” it announces that “you are producing bullets, bayonets, cannon, to murder not only the Germans, but also your dearest, best, who are in Russia and are fighting for freedom.” In contrast to the vaguer advocacy of the English leaflet, this one made a specific call for action:

Workers, our reply to the barbaric intervention has to be a general strike! An open challenge only will let the government know that not only the Russian Worker fights for freedom, but also here in America lives the spirit of revolution. Do not let the government scare you with their wild punishment in prisons, hanging and shooting. We must not and will not betray the splendid fighters of Russia. Workers, up to fight Woe unto those who will be in the way of progress. Let solidarity live!

This one was signed “The Rebels.”

Yiddish Language Leaflet titled “Workers Wake Up!” Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009. Public Domain.

Steimer took most of the leaflets to scatter surreptitiously around the city. She threw some from Lower East Side rooftops and several people who found them were so provoked that they contacted the police. A reserve squad and detectives “scoured the neighborhood in search of the perpetrators,” without success. Her distribution and the leaflets’ words were so shocking as to make New York City headlines the next day, reporting: “Wilson Attacked in Circulars from Roofs of East Side” and “Seditious Circulars Scattered in Streets.”

On August 23, 1918, Steimer took another batch to the factory she worked at, and tossed several out the bathroom window. Workers outside the building at 7:45 that morning looked up to see the leaflets fluttering down toward them. Although they couldn’t read the Yiddish words, they went to the police, who conducted a floor by floor search of the building. With thorough detective work, they found that an employee of the American Hat Company, Hyman Rosansky, had punched in earlier than usual that day. After questioning at police headquarters, Rosansky revealed that he was scheduled to pickup more leaflets from the group that evening on East 104th Street. (Steimer later described Rosansky as a “sympathizer” who “expressed a wish to participate” and that, when “caught and questioned, he gave us all out.”)

Staking out the rendezvous point from nearby doorways, the police ultimately nabbed Steimer and all the other group members one by one. The interrogations at police headquarters ranged from civil to violent. Steimer claimed that Lachowsky, Lipman, and Schwartz were severely beaten. By early the next morning, all of them confessed to their involvement, without implicating one another. The arrests of these anarchists for “attacking President Wilson and American war policy” made news. The Washington Times called them the “Blast Group,” and noted that the men “wore long hair and were heavily bearded.” The New York Journal characterized “the girl” as “defiant and of a quick and alert manner.”

The defendants were charged with violating the Sedition Act, enacted just three months earlier, which made almost all speech critical of the government a crime. This act was an amendment to the Espionage Act of 1917, which primarily criminalized obstructing recruitment to or causing insubordination in the military. Specifically, they were accused of conspiring to “unlawfully utter, print, write and publish . . . disloyal, scurrilous and abusive language” about the US government that was intended to bring it “into contempt, scorn, contumely and disrepute [and] . . . to incite, provoke and encourage resistance” to the war. In addition to Steimer and her associates, more than two thousand individuals would ultimately be prosecuted under the acts, resulting in over a thousand convictions.

The night before their trial, Jacob Schwartz died in the prison ward of Bellevue Hospital. An autopsy determined that pneumonia was the cause of death, but his fellow defendants vehemently rejected that conclusion and believed police brutality was to blame. His friends would place a wreath on his coffin that expressed their sentiments: “Jacob Schwartz, as the result of the Third Degree, on the night of his arrest, Aug. 23, died.” (During her trial testimony, the New York Tribune reported that Steimer “clenched her fist and almost screamed: ‘I insist that Schwartz was killed by the police!’”) An unfinished letter Schwartz had begun before being sent to the hospital helped to cast a legendary glow over what many anarchists viewed as his martyrdom for their cause: “Farewell, comrades. When you appear before the court I will be with you no longer. Struggle without fear, fight bravely. I am sorry I have to leave you.”

On October 14, the anarchist speech trial began in a Manhattan federal district court (the initial trial court in the federal system). Unfortunately for the defendants, a visiting judge from Alabama named Henry DeLamar Clayton Jr. would be presiding. Clayton was racist, anti–women’s suffrage, anti-immigrant, and anti-Semitic. One telling example of how these prejudices were blatantly displayed during the trial occurred when Judge Clayton became frustrated with the line of questioning from the defendants’ lawyer, Harry Weinberger. (Weinberger, whose parents were Hungarian Jewish immigrants, described himself as a “pugnacious little” fighter.) After refusing to allow Weinberger to continue speaking, Clayton told the court, “I have tried to outtalk an Irishman, and I never can do it, and the Lord knows I can not outtalk a Jew.”

Clayton seemed incapable of, or unconcerned about, hiding his distaste for the immigrant defendants. During Abrams’s testimony, he twice asked, “Why don’t you go back to Russia?” At another point with Abrams on the stand, Clayton demonstrated his unwillingness to consider the defendants as Americans. The revealing exchange is recounted in Professor Richard Polenberg’s richly detailed historical study, Fighting Faiths: The Abrams Case, the Supreme Court, and Free Speech:

Abrams, speaking in a soft voice with a distinct Yiddish accent, was earnestly attempting to defend his anarchist beliefs. “This government was built on a revolution,” Abrams said. “. . . When our forefathers of the American Revolution—” That was as far as he got. “Your what?” Judge Clayton interrupted. “My forefathers,” Abrams replied. “Do you mean to refer to the fathers of this nation as your forefathers?” Clayton asked. Abrams said, “We are all a big human family,” and “Those that stand for the people, I call them father.” But the judge had made his point, and the jury had no doubt gotten it.

Clayton’s condescending treatment of Steimer was no better, but she continued to rebelliously assert her beliefs. She refused to stand when the judge entered, and the bailiff called “all rise” to no avail. When questioned on whether or not she was an anarchist, Steimer pressed to define her philosophy in her own terms:

By anarchism, I understand a new social order, where no group of people shall be governed by another group of people. Individual freedom shall prevail in the full sense of the word. Private ownership shall be abolished. We shall not have to struggle for our daily existence, as we do now. No one shall live on the product of others. Everyone person shall produce as much as he can and receive according to his need. Instead of striving to get money, we shall strive towards educations, towards knowledge. To the fulfillment of this idea I shall devote all my energy, and, if necessary, render my life for it.

Weinberger made a strenuous final effort to persuade the jury to support free speech in an exhaustive two-hour closing argument. He contended that the defendants were not supporting the German cause, and therefore were not encouraging resistance to the American war effort. He maintained that even immigrant anarchists had “the right to question and protest against an army being sent to Russia, to fight the Bolsheviki. They had the right, not because they are American citizens, because they are not, but because they are here and free speech is guaranteed to all citizens and noncitizens.”

Despite Weinberger’s valiant efforts, the outcome of the two-week trial was hardly in doubt. After little more than an hour, the jury returned guilty verdicts for Abrams, Lachowsky, Lipman, Rosansky, and Steimer. On the day of the sentencing, the New York Tribune set the scene: “Mollie Steimer, a tiny person, dressed in a red Russian blouse, entered the court smiling, with flowers on her arm, which she gave to other defendants, except Rosansky, whom they ostracized because he had turned informer.” The United States attorney recommended leniency for Rosansky, because of his cooperation with the authorities, and he was sentenced to three years in the federal penitentiary. For the men, Clayton imposed the maximum sentence of twenty years each, and he gave Steimer fifteen.

As Steimer responded to her sentence, Clayton attempted to cut her off. “I’m not going to permit you to make a soapbox oration, Mollie,” he scolded her, “and this is one time that you are brought in contact with the knowledge that there is some authority even over an anarchist woman.” Nevertheless, she persisted. “Though you have sent troops to Russia,” Steimer announced to the courtroom, “though you have sent soldiers to slaughter our revolutionists, you cannot crush our revolutionary spirit.” The armistice bringing an end to World War I was only weeks away, but Steimer and her anarchist comrades’ constitutional battle for free speech had just begun.

A year had passed since the anarchists’ convictions by the time the Supreme Court heard their case in October 1919. Harry Weinberger summarized his brief in concise terms: “the point is put up . . . pretty straight as to whether or not you have the right to criticize the President and the policies of the government.” In his oral argument before the Court, Weinberger asserted that the freedom to speak out against the government had been protected by the framers of the constitution. Those revolutionaries viewed “the unabridgeable liberty of discussion as a natural right,” and therefore, he boldly claimed, the Sedition Act was unconstitutional.

Knowing that the Court had at that time never taken such an expansive view of the First Amendment, Weinberger also more pragmatically argued that there was insufficient evidence to support the jury verdict that the defendants had conspired to foster resistance to the war. He reiterated the point he had made to the jury, that in calling for a munitions factory strike, the defendants were not supporting Germany, but rather seeking to defend Russia. Even if some anti-war speech could constitutionally be made criminal, Weinberger maintained that this was speech of a different category. He characterized the leaflets as merely “a public discussion of a public policy in reference to a country with which we were not at war.”

Arguing on behalf of the government was Robert P. Stewart, who had been appointed earlier that year by President Wilson to be the first assistant attorney general in “charge of criminal matters” for the Department of Justice. Stewart’s main point was that the Court had upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act just seven months earlier in a case called Schenck v. United States. Since the Sedition Act was an amendment to the Espionage Act and put similar limits on speech, he insisted that the Abrams convictions must be “equally constitutional.” The Schenck case has been identified by University of Chicago law professor Geoffrey Stone as “the Supreme Court’s first significant decision interpreting the First Amendment.” In Schenck, during the war, two leaders of the Socialist Party had been found guilty of obstructing the draft and causing insubordination in the armed forces in violation of the Espionage Act. Their actions had been to print and distribute fifteen thousand leaflets attacking the draft (a “conscript is little better than a convict,” it said) and urging peaceful resistance to it (such as petitioning for the repeal of the act). Some of the leaflets were mailed directly to drafted men.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., writing for a unanimous Supreme Court, affirmed the convictions, including Schenck’s ten year sentence, in short order. The seventy-eight-year-old Justice Holmes had been born into a Boston Brahmin family (his father, a prominent physician and writer, coined the term “Brahmin” to describe New England’s elite), served in the Union army during the Civil War, and was a brilliant writer. He was tall and slim, dressed nattily, and sported an impressive white walrus mustache. Holmes looked and acted like a Hollywood vision of a Supreme Court justice: wise and regal. He was also an old-fashioned patriot who once said, “Damn a man who ain’t for his country right or wrong.”

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes seated in library, facing front, wearing a judicial robe. Photograph taken on 1903. Library of Congress.

Holmes’s reflexive support of the United States involvement in World War I may have influenced his decision to uphold Schenck’s conviction. Deploying his signature stylish turns of phrase, Justice Holmes expounded on why the specific limits on speech in the Espionage Act did not violate the First Amendment: We admit that, in many places and in ordinary times, the defendants, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.

With that fiery image, Holmes brought into the public consciousness what has been called “the most well-known—yet misquoted and misused—phrase in Supreme Court history.” It not only justified the wartime speech limitation for Schenck, but rhetorically spoke more broadly to the idea that limits on free speech should naturally be expected in our society. Like a zombie, Holmes’s metaphor continues lumbering on to our present day, stalking free speech wherever it goes, in the guise of universally accepted wisdom. People who want to restrict free speech invariably begin by saying some version of “you can’t yell fire. ” And while the sentence as written was certainly intended to be supportive of speech restrictions, it is consistently remembered incorrectly and used indiscriminately. Limits on “shouting fire” are justified, Holmes wrote, only if they are done “ falsely” and end up “causing a panic.” No one would ever think of punishing someone for yelling “fire” when there was actually a fire burning—in fact that person should be congratulated on potentially saving the lives of their fellow theatergoers! In addition, if there is no “panic” or harm, then any speech restriction is unnecessary, and even worse, may deter people from calling out a warning when one is needed. Both of these often forgotten components—falsity and harm—are crucial to comprehending the true limits of the First Amendment and should be prerequisites in any consideration of prohibiting speech. (If you, dear reader, take away nothing else from this book, please go forth and flaunt your knowledge of how to use this adage properly from now on.)

So in Schenck, Holmes and the Court had decided, with seemingly little handwringing, that the First Amendment had no power to stop the government from imprisoning people for nonviolent speech that criticized the government. Within days of that decision, the Supreme Court affirmed Espionage Act convictions in two more cases of anti-draft speech. The fact that the defendants in these cases were a presidential candidate and a newspaper publisher made no difference in their outcomes; each time, Justice Holmes delivered the opinion of the unanimous Court. Given these very recent and similar precedents, Assistant Attorney General Stewart had every reason to believe that another unanimous judgment in the government’s favor was sure to follow in Abrams. And yet, shockingly, Holmes himself was about to change course and lead the country on a new path toward a First Amendment revolution.

Seven justices on the Court had no difficulty deciding that the defendants’ convictions in Abrams should all be upheld. However, Justice Holmes, supported by his friend Justice Louis Brandeis, was thinking differently. As the majority opinion was being prepared, Holmes went to the upright desk in his home study and was about to write “twelve paragraphs that would change the history of free speech in America.” Immediately after finishing his dissenting opinion, Holmes wrote modestly in a letter to his friend Felix Frankfurter (the future Supreme Court justice) that he wasn’t sure what he had written “quasi in furore [as if possessed] . . . is good enough.” He needn’t have worried. What he wrote was so well reasoned and subversive that when he sent it around to his fellow justices for their consideration, it prompted a remarkable visit.

A week later, three justices of the Supreme Court arrived unannounced at Holmes’s town house. They were there to personally appeal to Holmes to reconsider his position, and join them in supporting the convictions of the anarchists and the validity of the Sedition Act. What happened next, and how they tried to convince him, is reconstructed in Professor Thomas Healy’s gripping intellectual history, The Great Dissent: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind— and Changed the History of Free Speech in America:

A dissent like this, [they argued,] from a figure as venerable as Holmes, might weaken the country’s resolve and give comfort to the enemy. The nation’s security was at stake, the justices told Holmes. As an old soldier, he should close ranks and set aside his personal views. They even appealed to [his wife] Fanny, who nodded her head in agreement. The tone of their plea was friendly, even affectionate, and Holmes listened thoughtfully. He had always respected the institution of the Court and more than once had suppressed his own beliefs for the sake of unanimity. But this time he felt a duty to speak his mind. He told his colleagues he regretted he could not join them, and they left without pressing him further.

Three days after the failed intervention, the Supreme Court’s decision in Abrams v. United States was announced. Justice John Clarke, the most junior member of the Court, wrote the opinion for the seven-member majority, affirming the convictions. (Only Brandeis joined Holmes in dissent.) Clarke dismissed what he described as the “faintly” argued First Amendment issues in a single sentence, holding that such claims had already been rejected in Schenck. Clarke also rejected Weinberger’s claim, “that the only intent of these defendants was to prevent injury to the Russian cause,” writing, “Men must be held to have intended, and to be accountable for, the effects which their acts were likely to produce.”

After Clarke’s summary of the case, Justice Holmes read his dissenting opinion from the bench to publicly emphasize how “grievously misguided” the majority opinion was in his view. Holmes began by articulating a demanding test for when “the right to free speech” could be restricted: “It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion.” Emphasizing how strict this test was in application, Holmes determined that “nobody can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man, without more, would present any immediate danger that its opinions would hinder the success of the government arms.”

Holmes went on to indignantly discuss the inappropriate harshness of the punishments: “In this case, sentences of twenty years’ imprisonment have been imposed for the publishing of two leaflets that I believe the defendants had as much right to publish as the Government has to publish the Constitution of the United States now vainly invoked by them.” Additionally, he called the motivation behind the severity of the sentences into question. “The most nominal punishment seems to me all that possibly could be inflicted,” Holmes opined, “unless the defendants are to be made to suffer not for what the indictment alleges, but for the creed that they avow.”

For his conclusion, Holmes constructed an expansive edifice that not only provided a rationale for his opinion in Abrams, but also for reconsidering the meaning of the First Amendment. In a little over four hundred words, he sought to convey why speech is dangerous, what free speech can do for society, and how strenuously we must resist the impulse to punish even the speech we hate. The result is the single most important paragraph in all of First Amendment law:

“Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power, and want a certain result with all your heart, you naturally express your wishes in law, and sweep away all opposition. To allow opposition by speech seems to indicate that you think the speech impotent, as when a man says that he has squared the circle, or that you do not care wholeheartedly for the result, or that you doubt either your power or your premises. But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas—that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year, if not every day, we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system, I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country. Only the emergency that makes it immediately dangerous to leave the correction of evil counsels to time warrants making any exception to the sweeping command, “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech.”

The impact of these words over time is hard to overstate. It would become “the most quoted paragraph ever written about the freedom of speech.” Even more meaningfully, it marked a turning point in recognizing the power of the First Amendment. This new vision of the First Amendment eloquently articulated why the government should be constitutionally prohibited from punishing Americans for their speech, simply because the government opposed or feared the ideas in that speech. It also placed dissenting voices at the center, not the margins, of First Amendment protection, even during wartime.

As noted dissenter Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has described, since a dissent does not decide a case or create a rule of law, one of its primary purposes is for “appealing to the intelligence of a future day.” The Abrams dissent certainly achieved this goal, but it also did something more. Harvard Law Professor Mark Tushnet has written that a truly great dissent is one in which “its vision of democracy and the Constitution and its rhetoric themselves contributed to making its doctrine seem correct.” Holmes’s words measure up to that rare distinction: they not only spoke to the future, they transformed it.

Central to this new free speech perspective was the metaphor Holmes conjured up that became known as the “marketplace of ideas.” Although Holmes himself never used that term, it nevertheless captures the spirit of this unique justification for free speech. Holmes turns to the chaos and cacophony of the market place to convey the connection between America’s democratic capitalism and the value of searching for truth in a forum where the government cannot exclude critical voices from the public debate. It also seems possible that Holmes strategically chose an economic symbol to make his revolutionary defense of anti-capitalist speech more persuasive to his conservative contemporaries.

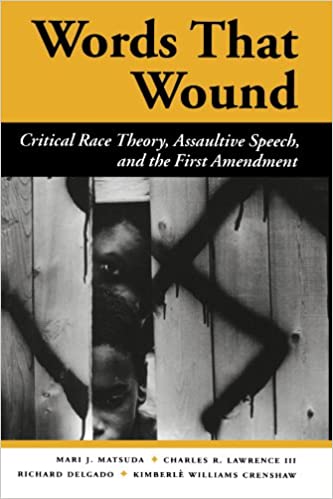

In 1993, legal scholar Mari Matsuda published “Words that Wound,” a collection of essays critiquing absolute protections for hate speech from a critical race perspective. The book includes a section written by Charles R. Lawrence III on regulating racist speech on campus.

While celebrating the theoretical potential for the marketplace of ideas to encourage openness to a wide variety of speech, we should not, however, fail to recognize the substantial body of academic critique that has challenged the marketplace of ideas theory. Much of this discussion centers around the question of: who is truly heard in the marketplace? If women, minorities, and poor people are not granted equal opportunity to enter the market, how can their voices participate in the competition for truth? As University of Hawaii at Manoa professor of law emeritus, and a leading expert on anti-discrimination law and critical race theory, Charles R. Lawrence III puts it, “We must eschew abstractions of first amendment theory that proceed without attention to the dysfunction in the marketplace of ideas created by racism and unequal access to that market.” Even when access issues are addressed, feminist legal pioneer Professor Catharine A. MacKinnon further calls into question whether disenfranchised groups ever really benefit from the marketplace forum:

Think about whether the speech of the Nazis has historically enhanced the speech of the Jews. Has the speech of the Klan expanded the speech of Blacks? Has the so-called speech of pornographers enlarged the speech of women? In this context, apply to what they call the marketplace of ideas the question . . . : Is there a relationship between our poverty in speech and their wealth?

In addition to these equity concerns, the prospect of a market leading to truth is hard for many consumers to swallow. The free market may be an effective economic system, but how does a mechanism designed to enable selling act as a model to facilitate truth seeking? The influence of money and advertising dollars in a market-based system also raises real concerns about truth resulting from a process in which wealth buys you a bigger and better megaphone.

Mark Twain is credited with saying that “a lie can travel around the world and back while the truth is still lacing up its boots.” And that perception is supercharged in today’s social media–paced world, in which the truth can be swamped under a tweet storm of instant falsehoods. There are those who would argue that whatever value the marketplace metaphor had in the past, it is becoming quickly outmoded in our internet age.

All of these powerful critiques provide revealing insights into American society and justify ongoing debate. At the same time, in order to have any kind of meaningful discussion about free speech today it remains necessary to engage with Holmes’ enduring marketplace conception. Grappling with the marketplace of ideas is vital for both those who seek to support our country’s current approach to free speech and for those who wish to change it.

Putting metaphor and theory aside, how did the Abrams dissent practically change the law regarding advocacy of illegal action? The short answer to this complex question is that it didn’t—at least not for a long time. It took more than a decade until the Supreme Court struck down a speech-restricting statute as unconstitutional on First Amendment grounds. And it was not until fifty years after Abrams, in a case called Brandenburg v. Ohio, that a version of the test Holmes and Brandeis suggested in their dissent fully evolved into its modern and lasting form. The Brandenburg holding states that “the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” In other words, only speech advocating illegal conduct that is directed and likely to trigger imminent illegal action is not protected by the First Amendment, and therefore can be prohibited. This progression, from punishment of speech about criminal conduct to robust protections for such speech, is directly attributable to Holmes’s decision to change his mind in Abrams.

The remarkable evolution of First Amendment rights from virtually nonexistent to possessing superhero-like strength demonstrates our country’s common law judicial system in action. The “common law” means law that comes from judicial interpretation and decisions, rather than legislative statutes. Each decision builds on the next, with courts abiding by the past decisions (often called precedents) of the courts above them in their system.

Holmes literally wrote the book on this subject. His groundbreaking classic The Common Law, published in 1881 as he turned forty, begins by declaring, “The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.” What Holmes meant by this was that the common law is not focused on mathematical precision, but rather develops over time as society changes, based in large part on the experiences of judges and the parties before them. Whether you find this process an inspiring one of messily evolving liberty or look with cynicism at its often-lurching inconsistency, the Abrams case and its influence reflect the common law nature of our system for good and ill. And in doing so it provides an origin story that is indispensable to understanding the First Amendment today.

* * *

While it’s all well and good to talk about the triumph of First Amendment values over a half century, what did the Abrams decision mean at the time for the anarchists? It meant they went to prison. The Supreme Court majority, despite the protestations of Holmes and Brandeis, had rejected the defendants’ claims and so the convictions stood. By December 1919, Abrams, Lipman, Lachowsky, and Steimer had all begun serving their terms of fifteen to twenty years. They would remain incarcerated for the next two years, until the tireless lobbying efforts of their lawyer Weinberger were finally successful. He was able to get the new administration of President Warren Harding to commute their sentences on the condition that they be “at once deported to Russia, never to return.”

Steimer initially refused to accept an amnesty deal. “I don’t want to be deported. I don’t want to be pardoned,” she told the authorities. “You sentenced me; when all political prisoners will be freed, I will be freed.” But she later said she was ultimately prevailed upon to go along with the plan “when I was told that the boys are . . . only waiting for me.”

A newspaper announces in English and Yiddish that Mollie Steimer, who was deported from the United States for violating the Espionage Act, is now being exiled from Russia. “Mollie Steimer, who was deported from the U.S. in 1921 because of her radicalism, has just been exiled from Russia, and for a similar ‘crime.'” From the Alvrich Collection in the Library of Congress.

On November 23, 1921, Abrams, Lachowsky, Lipman, and Steimer were ready to depart to Russia from a pier in South Brooklyn aboard the SS Esthonia. The group had mixed emotions as they prepared to leave their loved ones and America forever, to face an uncertain future. Steimer stoically told sixty friends and family that had gathered to see them off, “Good-bye, all of you. I hope that America will be freer in the future than it is today.”

From that time onward, their lives would be filled with even greater hardships. Persecuted and jailed in Russia for her anarchist beliefs, Steimer once again had no choice but to accept deportation. This time her only alternative was to suffer through three years of imprisonment in a gulag. Lipman, who had become a Communist and a profes- sor of economic geography, was killed in the Stalinist purges of the late 1930s. And Lachowsky was most likely murdered in his native Minsk by the Nazis sometime after 1941.

Abrams and Steimer separately managed to make their way to Mexico by 1942. Steimer would live there for the rest of her days, never setting foot again in America, and through it all remained steadfastly committed to anarchist causes until her death in 1980. When she was sixty-three, Steimer described her lifelong struggle for what they believed in: “We fought injustice in our humble way as best we could; and if the result was prison, hard labour, deportations and lots of suffering, well, this was something that every human being who fights for a better humanity has to expect.”

* * *

As a person who always spoke her mind and refused to accept the status quo, Steimer would likely have felt right at home with the participants of the Women’s March. She may also have appreciated Madonna’s fearlessness in breaking cultural norms. Madonna’s remark about having “thought an awful lot about blowing up the White House” would not have shocked Steimer, although the lack of action taken against the speech might have surprised her.

The fact is that Madonna’s statement would certainly be protected under the Brandenburg test, since it was neither “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action” from the crowd, nor “likely to incite or produce such action.” And Steimer deserves recognition for her role in making such speech, and even more broadly speech that criticizes the government, protected under the First Amendment. On the day of her deportation nearly one hundred years ago, Mollie Steimer expressed the hope that America would be freer in the future. Her hope came to pass, and our speech is freer today than it ever would have been without her.

One of the largest single-day protests in U.S. history, the 2017 Women’s March on Washington took place the day after the inauguration of President Donald Trump. Mark Dixon, Wikimedia Commons.

Tags