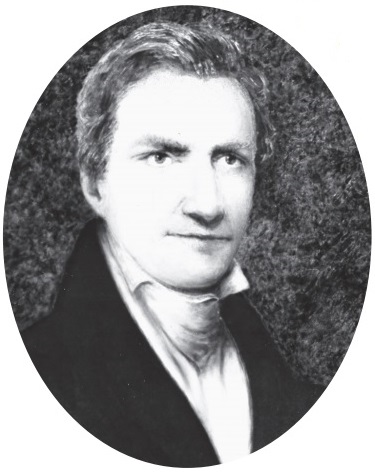

James Madison, Hamilton’s major collaborator, later President of the United States and “Father of the Constitution” (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

By Professor Stephen D. Solomon, Editor, First Amendment Watch, with valuable assistance from Maddie Donatucci, NYU 2021

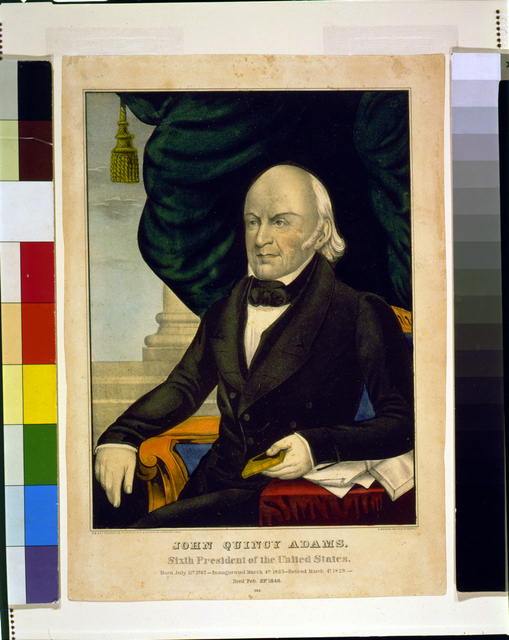

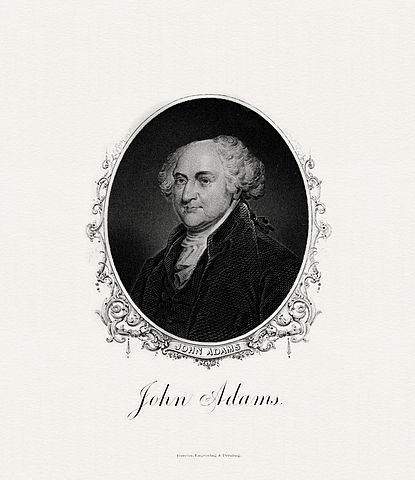

James Madison, author of the First Amendment, wrote what is surely the most powerful defense of freedom of the press in America. He did it in protest against the Sedition Act of 1798, enacted just seven years after ratification of the First Amendment. At a time when the United States and France were on the verge of war, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts to deal with the perceived threat of internal insurrection and dissent. John Adams and his Federalist Party used the law to prosecute more than a dozen critics of his administration, most of them journalists, and five opposition (Democratic-Republican) newspapers closed.

The Sedition Act made it illegal to “write, print, utter, or publish . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing” against Congress or the President. In 1799, Henry Lee defended Alien and Sedition Acts after the Virginia House of Delegates voted in favor of resolutions condemning the laws. Lee wrote that the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution empowered Congress to pass the Sedition Act. If the government had the power to punish resistance, then it did not have to wait until resistance occurred; it also had the power to punish speech before it could incite resistance.

He argued that “the” freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment was nothing more than the freedom recognized by the common law of England—that is, the freedom from prior restraints on publication and not punishment for criticism of government once published.

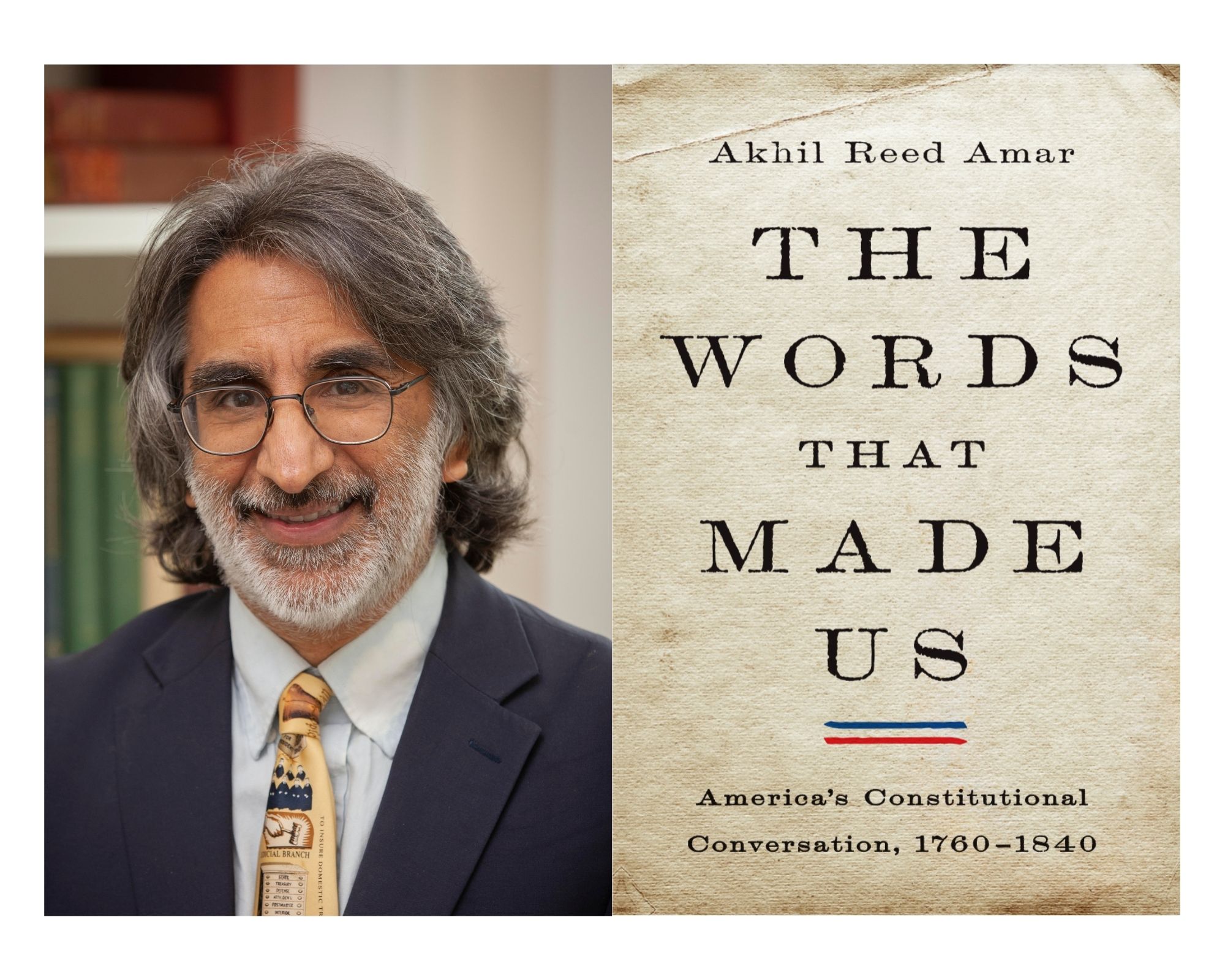

Cover of Madison’s 1800 report

Madison’s powerful answer came a year later, in 1800, with his Report on the Virginia Resolutions. His arguments for freedom of speech and press ranged widely—including his charge that Congress had no power to legislate over the press and that freedom of the press was inextricably tied to the American commitment to self-governance in a democratic society.

The portion of Madison’s Report that defends freedom of the press can be read in its entirety here. To make Madison’s defense more accessible, we summarize many of his arguments below and include relevant quotations. Click on links to scroll to relevant section.

Self Governance in America Requires Public Discussion

The Press Played a Central Role in the Revolution

The Defense of Truth Proves to be Frail

Congress Lacked the Power to Enact the Sedition Act of 1798

A Different Form of Government in America Requires Vigorous Protections for Speech

__________________________

Self Governance in America Requires Public Discussion

Perhaps Madison’s most important contribution was his argument that freedom of speech and press was part of the very fabric of a democratic form of government. In America, he argued, the people must enjoy the right to openly discuss and debate their opinions about the government and public officials. If free speech is denied, it is that much easier for other rights to be stripped away because no one will be able to speak out against it. Madison warned that laws prohibiting speech should cause “universal alarm” because the country would be veering away from democracy and embracing the very type of government that the colonies revolted against.

Excerpt

“And, in the opinion of the committee, well may it be said, as the resolution concludes with saying, that the unconstitutional power exercised over the press by the ‘sedition act,’ ought ‘more than any other, to produce universal alarm; because it is levelled against that right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed the only effectual guardian of every other right.’

“May it not be asked of every intelligent friend to the liberties of his country, whether the power exercised in such an act as this ought not to produce great and universal alarm? Whether a rigid execution of such an act, in time past, would not have repressed that information and communication among the people, which is indispensible to the just exercise of their electoral rights? And whether such an act, if made perpetual, and enforced with rigor, would not, in time to come, either destroy our free system of government, or prepare a convulsion that might prove equally fatal to it?”

“For omitting the enquiry, how far the malice of the intent is an inference of the law from the mere publication; it is manifestly impossible to punish the intent to bring those who administer the government into disrepute or contempt, without striking at the right of freely discussing public characters and measures: because those who engage in such discussions, must expect and intend to excite these unfavorable sentiments, so far as they may be thought to be deserved.

“Old City Hall, Wall St., N.Y.” Steel engraving by Robert Hinshelwood, from Washington Irving’s Life of George Washington, 5 vol. (1855-59)

“Let it be recollected, lastly, that the right of electing the members of the government, constitutes more particularly the essence of a free and responsible government. The value and efficacy of this right, depends on the knowledge of the comparative merits and demerits of the candidates for public trust; and on the equal freedom, consequently, of examining and discussing these merits and demerits of the candidates respectively.”

“Should there happen, then, as is extremely probable in relation to some or other of the branches of the government, to be competitions between those who are, and those who are not, members of the government; what will be the situations of the competitors? Not equal; because the characters of the former will be covered by the ‘sedition act’ from animadversions exposing them to disrepute among the people; whilst the latter may be exposed to the contempt and hatred of the people, without a violation of the act. What will be the situation of the people? Not free; because they will be compelled to make their election between competitors, whose pretensions they are not permitted by the act, equally to examine, to discuss, and to ascertain. And from both these situations, will not those in power derive an undue advantage for continuing themselves in it; which by impairing the right of election, endangers the blessings of the government founded on it?”

“It is with justice, therefore, that the General Assembly hath affirmed in the resolution, as well that the right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication thereon, is the only effectual guardian of every other right; as that this particular right is leveled at, by the power exercised in the Sedition Act.”

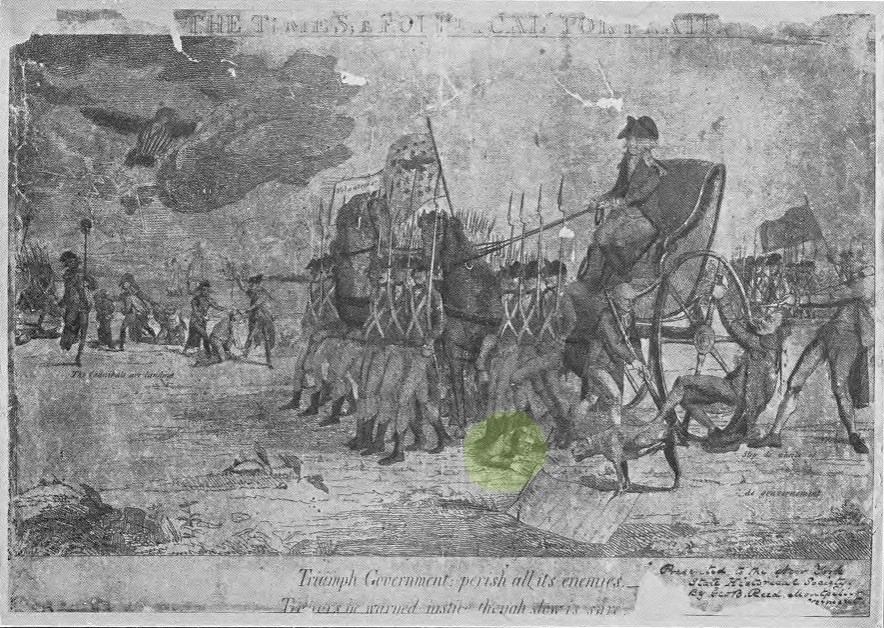

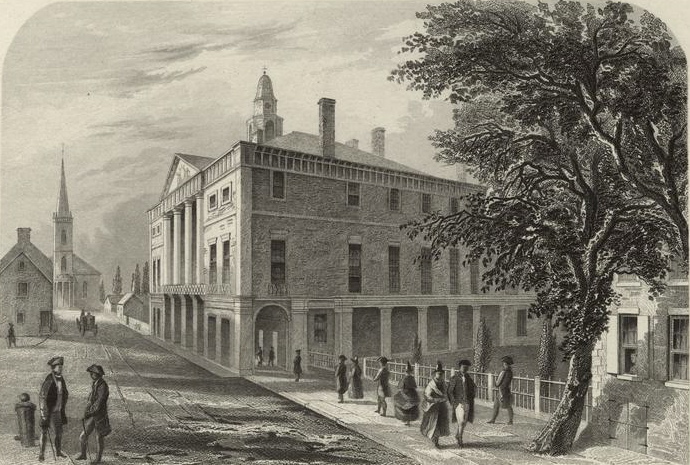

The Press Played a Central Role in the Revolution

Madison pointed out the critical role of the press leading up to and during the American Revolution. Although criticism of government and public officials could be criminally punished under seditious libel laws, those who protested against British policy in America—writers, , poets, cartoonists, newspaper publishers, and the wide swath of citizenry who participated in demonstrations—acted as if the law did not exist. It proved almost impossible for officials to obtain indictments or convictions for seditious libel from colonial juries. If the patriots had obeyed the seditious libel laws, it is likely the revolution never would have happened, and the colonists would likely still be living under the rule of a repressive English government.

Excerpt

Massachusetts Spy

“Some degree of abuse is inseparable from the proper use of every thing; and in no instance is this more true, than in that of the press. It has accordingly been decided by the practice of the states, that it is better to leave a few of its noxious branches, to their luxuriant growth, than by pruning them away, to injure the vigor of those yielding the proper fruits. And can the wisdom of this policy be doubted by any who reflect, that to the press alone, chequered as it is with abuses, the world is indebted for all the triumphs which have been gained by reason and humanity, over error and oppression; who reflect that to the same beneficent source, the United States owe much of the lights which conducted them to the rank of a free and independent nation; and which have improved their political system, into a shape so auspicious to their happiness.”

“Had ‘Sedition acts,’ forbidding every publication that might bring the constituted agents into contempt or disrepute, or that might excite the hatred of the people against the authors of unjust or pernicious measures, been uniformly enforced against the press; might not the United States have been languishing at this day, under the infirmities of a sickly confederation? Might they not possibly be miserable colonies, groaning under a foreign yoke?”

“The practice in America must be entitled to much more respect. In every state, probably, in the union, the press has exerted a freedom in canvassing the merits and measures of public men, of every description, which has not been confined to the strict limits of the common law. On this footing, the freedom of the press has stood; on this footing it yet stands.”

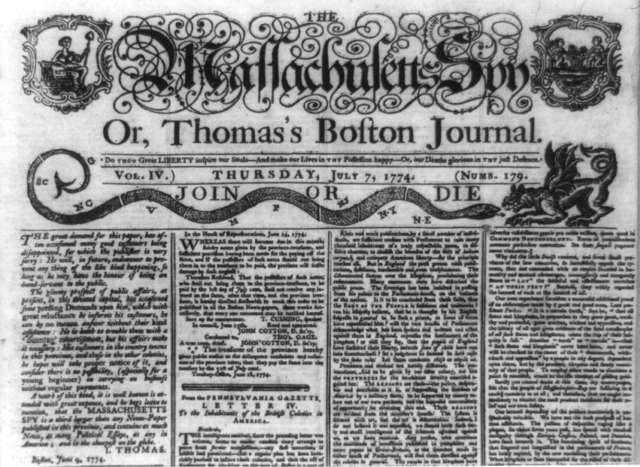

The Defense of Truth Proves to be Frail

Ironically, the 1798 law finally elevated truth as a defense to a seditious libel prosecution, an advance that libertarians had wanted for centuries. But it soon became clear that a defense of truth would not protect dissenters from prosecution. Writers and speakers had been jailed for voicing opinions, which unlike factual statements are not capable of being proved true. And, as Madison recognized, it is often difficult to prove whether facts are true or not. For these reasons, Madison encouraged further defenses against claims than simply the accuracy of the alleged libel.

U.S. Representative Matthew Lyon (Vermont), convicted and jailed for violation of the Sedition Act of 1798. credit: By Billmckern – State House Portrait, CC BY-SA 4.0

Excerpt

“…it has been pleaded that the writings and publications forbidden by the act, are those only which are false and malicious, and intended to defame;…”

“In the first place, where simple and naked facts alone are in question, there is sufficient difficulty in some cases, and sufficient trouble and vexation in all, of meeting a prosecution from the government, with the full and formal proof, necessary in a court of law.”

“But in the next place, it must be obvious to the plainest minds, that opinions, and inferences, and conjectural observations, are not only in many cases inseparable from the facts, but may often be more the objects of the prosecution than the facts themselves; or may even be altogether abstracted from particular facts; and that opinions and inferences, and conjectural observations, cannot be subjects of that kind of proof which appertains to facts, before a court of law.”

Congress Lacked the Power to Enact the Sedition Act of 1798

Supporters of the Sedition Act argued that Congress had power under the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution (Article I, Section 8) to enact restrictions on the press. The Clause states that Congress had power to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers.” Because Congress had the power to stop insurrections, it must have the power to punish speech that tended to lead to that result. Madison disagreed and pointed out that the Constitution gave Congress no power over the press, and that the First Amendment was ratified as an express denial of any such power. “The federal government,” Madison concluded, “is destitute of all such authority.

Excerpts

“…it was invariably urged to be a fundamental and characteristic principle of the constitution; that all powers not given by it, were reserved; that no powers were given beyond those enumerated in the constitution, and such as were fairly incident to them; that the power over the rights in question, and particularly over the press, was neither among the enumerated powers, nor incident to any of them; and consequently that an exercise of any such power, would be a manifest usurpation. It is painful to remark, how much the arguments now employed in behalf of the sedition act, are at variance with the reasoning which then justified the constitution, and invited its ratification.”

“Without tracing farther the evidence on this subject, it would seem scarcely possible to doubt, that no power whatever over the press, was supposed to be delegated by the constitution, as it originally stood; and that the amendment was intended as a positive and absolute reservation of it.”

Text of Alien Act (1798)

Text of Sedition Act

“Under any other construction of the amendment relating to the press, than that it declared the press to be wholly exempt from the power of Congress, the amendment could neither be said to correspond with the desire expressed by a number of the states, nor be calculated to extend the ground of public confidence in the government. Nay more; the construction employed to justify the ‘sedition act,’ would exhibit a phenomenon, without a parallel in the political world. It would exhibit a number of respectable states, as denying first that any power over the press was delegated by the constitution; as proposing next, that an amendment to it, should explicitly declare that no such power was delegated; and finally, as concurring in an amendment actually recognizing or delegating such a power.”

“Is then the federal government, it will be asked, destitute of every authority for restraining the licentiousness of the press, and for shielding itself against the libellous attacks which may be made on those who administer it? The constitution alone can answer this question. If no such power be expressly delegated, and it be not both necessary and proper to carry into execution an express power; above all, if it be expressly forbidden by a declaratory amendment to the constitution, the answer must be, that the federal government is destitute of all such authority.”

“Words could not well express, in a fuller or more forcible manner, the understanding of the convention, that the liberty of conscience and the freedom of the press, were equally and completely exempted from all authority whatever of the United States.”

“Under an anxiety to guard more effectually these rights against every possible danger, the convention, after ratifying the constitution, proceeded to prefix to certain amendments proposed by them, a declaration of rights, in which are two articles providing, the one for the liberty of conscience, the other for the freedom of speech and of the press.”

“The plain import of this clause is, that Congress shall have all the incidental or instrumental powers, necessary and proper for carrying into execution all the express powers; whether they be vested in the government of the United States, more collectively, or in the several departments, or officers thereof. It is not a grant of new powers to Congress, but merely a declaration, for the removal of all uncertainty, that the means of carrying into execution, those otherwise granted, are included in the grant.”

“…in most of the states, the ratifications were followed by propositions and instructions for rendering the constitution more explicit, and more safe to the rights, not meant to be delegated by it.”

“To place this resolution in its just light, it will be necessary to recur to the act of ratification by Virginia which stands in the ensuing form… ‘We, the delegates of the people of Virginia…and that, among other essential rights, the liberty of conscience and of the press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained, or modified, by any authority of the United States.’”

A Different Form of Government in America Requires Vigorous Protections for Speech

In England, sovereignty lay with Parliament, which was the guardian of the rights of the people against the king. Madison pointed out that the situation in America was different. The Constitution created a republic based on popular sovereignty and self-governance, and the people’s rights needed to be safeguarded against encroachments by both the legislative and executive branches. The right to freedom of the press required a much broader conception than was followed in England. Americans needed safeguards to enable them to critique the actions of those whom they had elected to represent them. “In the United States,” Madison wrote, “the executive magistrates are not held to be infallible, nor the legislatures to be omnipotent; and both being elective, are both responsible. Is it not natural and necessary, under such different circumstances, that a different degree of freedom, in the use of the press, should be contemplated?”

Excerpt

“And, in the opinion of the committee, well may it be said, as the resolution concludes with saying, that the unconstitutional power exercised over the press by the Sedition Act ought, “more than any other, to produce universal alarm; because it is levelled against that right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed the only effectual guardian of every other right.””

Henry Lee

“In the British government, the danger of encroachments on the rights of the people, is understood to be confined to the executive magistrate. The representatives of the people in the legislature, are not only exempt themselves, from distrust, but are considered as sufficient guardians of the rights of their constituents against the danger from the executive.”

“Hence too, all the ramparts for protecting the rights of the people, such as their magna charta, their bill of rights, &c. are not reared against the parliament, but against the royal prerogative. They are merely legislative precautions, against executive usurpations. Under such a government as this, an exemption of the press from previous restraint by licensers appointed by the king, is all the freedom that can be secured to it.

In the United States, the case is altogether different. The people, not the government, possess the absolute sovereignty. The legislature, no less than the executive, is under limitations of power. Encroachments are regarded as possible from the one, as well as from the other. Hence in the United States, the great and essential rights of the people are secured against legislative, as well as against executive ambition.

“The nature of governments elective, limited, and responsible, in all their branches, may well be supposed to require a greater freedom of animadversion than might be tolerated by the genius of such a government as that of Great Britain. In the latter, it is a maxim, that the king, an hereditary, not a responsible magistrate, can do no wrong; and that the legislature, which in two thirds of its composition, is also hereditary, not responsible, can do what it pleases. In the United States, the executive magistrates are not held to be infallible, nor the legislatures to be omnipotent; and both being elective, are both responsible. Is it not natural and necessary, under such different circumstances, that a different degree of freedom, in the use of the press, should be contemplated?”

“…the freedom exercised by the press, and protected by the public opinion, far exceeds the limits prescribed by the ordinary rules of law. The ministry, who are responsible to impeachment, are at all times, animadverted on, by the press, with peculiar freedom; and during the elections for the House of Commons, the other responsible part of the government, the press is employed with as little reserve towards the candidates.”

Compiled by Maddie Donatucci, NYU 2021