By Soraya Ferdman

In his new book, The First Amendment in the Trump Era, Timothy Zick, a John Marshall Professor of Government and Citizenship and Cabell Research Professor at William and Mary Law School, illustrates the extent to which Donald Trump’s presidency is a marked departure from our country’s commitment to free and open discourse. Written for those who are skeptical that current threats to free speech are ‘as bad as they say,’ Zick argues that most presidents have criticized journalists, whistleblowers, and protesters, but few presidents have made doing so a central point of their public agenda.

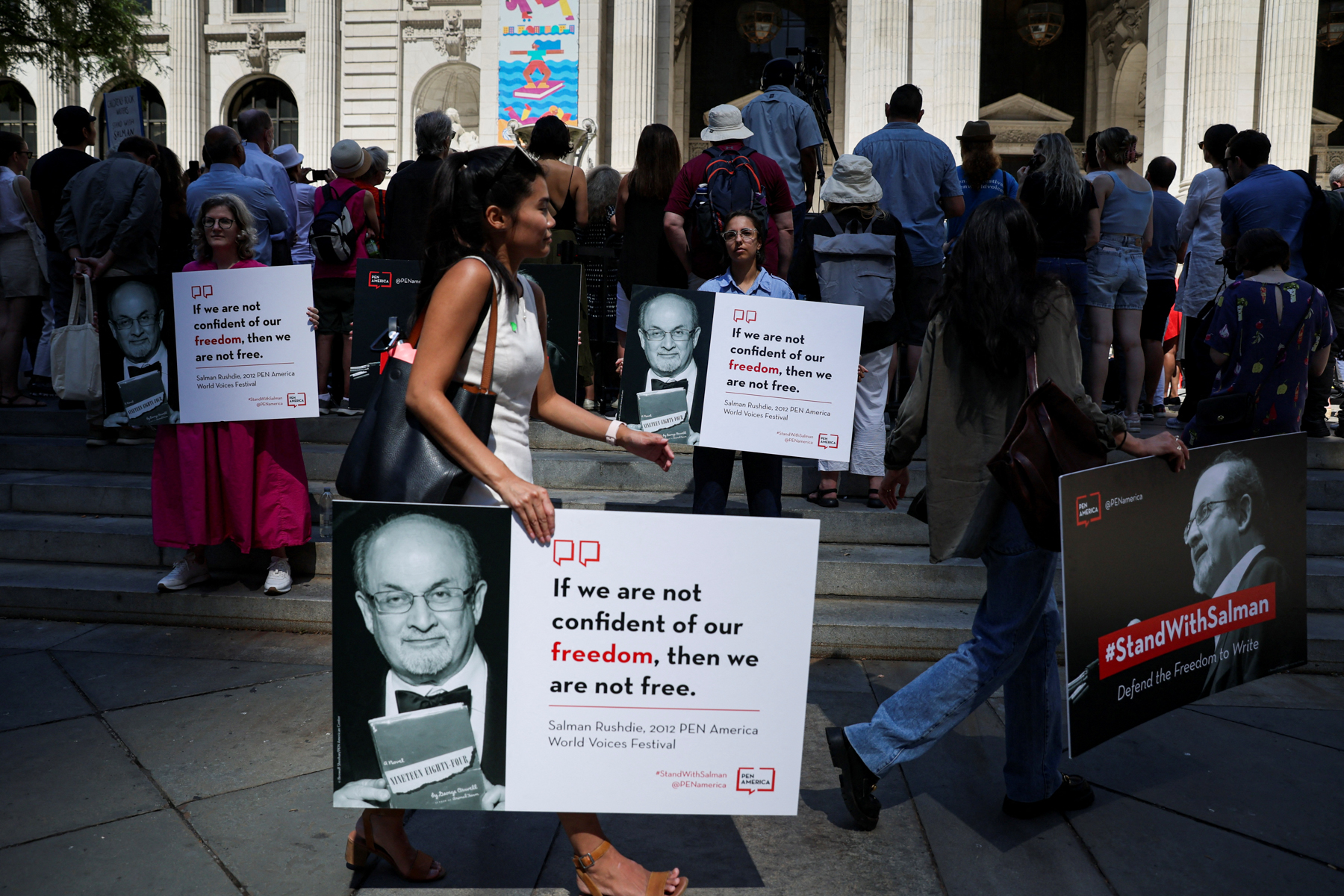

First Amendment staff writer Soraya Ferdman spoke to Zick about the specific threats this presidency poses to First Amendment protections, as well as the particular conditions in today’s media landscape that makes the press vulnerable to these attacks. Zick has also given First Amendment Watch permission to publish an excerpt from Chapter 3 of his book, “The Anti-orthodoxy Principles,” which uses the lessons from two famous First Amendment Supreme Court cases, West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette and Texas v. Johnson to demonstrate how Trump’s criticism of the NFL protests erodes the public’s appreciation for dissent and its role in a democracy.

The book is as much a portrait of today’s free speech landscape as a refresher in First Amendment history. Zick highlights the fragility of narrowly won protections for free speech and press, and the very real need to defend them.

Read a book excerpt of The First Amendment in the Trump Era here.

Note: This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Ferdman: At the core of the book is the assertion that this presidency poses unique threats to the First Amendment that deserve special scrutiny. Am I right to say that?

Zick: Yes, I think so.

Ferdman: Why do you think it’s important to articulate how Trump’s behavior differs so radically from other presidents?

Zick: Of course you often hear that: He’s not the first president to have complained about the press. No president likes to be criticized. But, what’s distinctive about him in that regard, is that he’s made a public agenda item to discredit, not just the press, but any critic; any algorithm, any comedy show that deigns to criticize what he does. And he’s very transparent about that. He said to one television interviewer “my agenda is to make sure that people don’t trust the press.”

And there’s some evidence that that’s working. Polling suggests that respondents think the press should be subject to stricter limits or the government should have more control over the press. In that sense, he’s distinctive.

Ferdman: You write in your chapter on a free and independent press, “President Trump’s public, vitriolic, and incessant peace-time campaign to discredit the media has no historic analog.” I’m looking at these three adjectives, “public” “vitriolic” and “incessant” and I’m curious about how you chose them.

Zick: Part of what’s distinctive about this president is that he doesn’t speak through press secretaries or officials. He does it himself on Twitter. And then the media replays these tweets over and over again, sort of reads them out loud and analyzes them. So, you have this constant feeling of a public attack on the credibility of the press.

I think the implication is that these are individuals that are not just dishonest, but are enemies of the people–and that’s a phrase that he’s used, borrowed from autocrats, and used persistently. In terms of vitriol, it’s very ad hominem. It’s personal, but it’s also, leading to this implication that these are the enemies of the country, and [that] you should be wary of them. Not only that, if you’re at a rally, there’s even the implication that you should be violent towards them—there have been violent episodes with regards to members of the press. Some doubt that you can’t link his language to that directly, causally, but [his language] creates a public environment where this is always on the agenda.

And as I try to note in the book, Trump didn’t create that condition—he’s exploited it. And he’s taken it to what I consider to be a dangerous level.

“I think dissent is the lifeblood of democracy. I think it’s what’s driven every notable social, cultural, and constitutional change that has propelled us in a forward direction.”

Ferdman: What makes the press so vulnerable to these kinds of attacks?

Zick: There was digitization, which was partly responsible for declining subscriptions, and a fracturing of the media landscape. There were already in place changing relationships between public officials and the press. Press scholars have noted a decrease in judicial support for the press. For instance, that the Supreme Court no longer speaks in glowing terms about the press. In lower courts, media outlets are losing cases with regard to what counts as newsworthy. That’s something they use to get a fair amount of deference with regard to. And that seems to be slipping.

And then sort of globally, the growth of this post-truth culture, all of those things are perfectly set up for what Trump has now tried to do. He’s the perfect archetype for an era with those conditions: He’s hyper-communicative, he’s hyper-combative, he’s hyper-partisan, and he is deeply polarizing.

Ferdman: Putting aside digitization and its special role in contemporary culture, is there historical precedent for public anxiety about the accuracy of information used in public discourse? You cite in your book that Thomas Jefferson talked about how newspapers eroded the truth. Isn’t there a history to this?

Zick: There’s always been propaganda. There’s always been efforts to misinform the public with regard to public policies. So, yes, there are historical analogs, but I think we’re in a place where post-truth really does have a different meaning. That if the very first thing a president’s press secretary does is to say “that was the biggest inaugural crowd you’ve ever seen”, when that’s demonstrably false? That sort of boldness of challenging objective fact… This is just in your face: what you think is not true and let me tell you what the truth is. I think there’s a difference.

U.S. President Donald Trump points to a large “Merry Christmas” card on the stage as he arrives to deliver remarks on tax reform in St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. November 29, 2017. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

Ferdman: When does Trump’s brand of “America First” become a First Amendment threat? When is he allowed to express patriotism and when does it turn into something more coercive?

Zick: I try to draw this distinction in the book: the president as a speaker who has his own right to express his opinions, versus when the government uses its coercive power to regulate the speech of others. Certainly, if he used his power over the postmaster to punish Jeff Bezos and his company because Bezos is a critic of the president, that’s a problem.

In terms of orthodoxy, in terms of imposing a nationalistic vision of the country, I think the NFL players [protest] is one of the best examples of his attempt to do that. Again, if he did take some course of action with regard to the players, that would be a First Amendment violation. Whether or not he does that, he is poisoning the well, in a sense, pressuring Americans, dividing them into camps that are real Americans and unpatriotic Americans, dismissing or failing to even hear the message that those protests were meant to send, and using his office to communicate his vision of what it means to be a real American.

I think that has an impact on a culture with regard to one’s willingness to stand up to that kind of bullying or to disagree with what the president says is a real American. When he says or suggests that we should take a flag burner [who is] presumably engaged in political protest and not just jail them, but strip them of their citizenship… people say, well, you shouldn’t take that literally or seriously, but I think it’s a mistake to simply ignore it or laugh it off. It’s one of the many things he’s said that suggests that if he could, he seemingly would exercise that power.

Ferdman: Can you talk about why it’s significant that this is all happening outside a time of war?

Zick: One of the phenomenal things about this era is that it’s been a relative peace-time. And still there’s this effort to sort of crush dissent, which has now been defined as anything critical of the President or the administration. Historically, dissent suffers during war time and the reasons for that are obvious. For a lot of people, probably even understandable. When you have soldiers in foreign theaters of war, domestic dissent can have a detrimental effect on public support for the war. I don’t think any of those are reasons to suppress dissent, but I think that’s distinctive from a situation of relative peace-time.

Ferdman: I noticed that you dedicated your book to dissenters. Obviously, you’re a First Amendment scholar so you’ll have a kind of natural inclination to value dissent, but what in your experience has convinced you of its importance?

Zick: I think dissent is the lifeblood of democracy. I think it’s what’s driven every notable social, cultural, and constitutional change that has propelled us in a forward direction. To the extent that the book is about a war on dissenters, I definitely wanted to give a shout out to people who engage in dissent because it’s difficult work.

A man kneels with a folded U.S. flag as the motorcade of U.S. President Donald Trump passes him after an event at the state fairgrounds in Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S., September 27, 2017. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst/File

You can read a book excerpt of Timothy Zick’s book The First Amendment in the Trump Era here.