If you’ve already read Part I, click here to scroll down to Part II.

Foreword by Stephen D. Solomon, Editor, First Amendment Watch and Marjorie Deane Professor of Journalism, New York University

Here is a story about a president who lashed out at the press and thought that his critics were dangerous—and should even be thrown in jail.

No, this is not President Donald Trump. More than two centuries earlier, during a time of rising tensions with France, America’s second president, John Adams, excoriated his critics for their “tongues and pens of slander” and for their “profligacy, falsehood, and malignancy, in defaming our government.” For Adams and his Federalist party supporters, criticism was a serious political threat. They responded with the Sedition Act of 1798, the most odious anti-speech law in U.S. history. Any criticism of Adams or the Federalist controlled Senate and House could land a person in jail. And that’s where more than a dozen critics of the Adams Administration ended up.

One of the primary targets of the law was Benjamin Franklin Bache, grandson of Benjamin Franklin, and publisher of the Aurora, an opposition newspaper in Philadelphia that scorned Adams at every turn. Though Bache may have escaped the Sedition Act, it was only because death by yellow fever took care of him before Adams could.

Bache is almost a forgotten figure. But as legal scholar and historian Ronald K. L. Collins makes clear in two fascinating essays we’re publishing in First Amendment Watch, Bache was the most important of a group of journalists of his day who “tested the fiber of the First Amendment like no one since.” The resolution of that test has reverberated to our own day. As the Supreme Court said in New York Times v. Sullivan, the Sedition Act “first crystallized a national awareness of the central meaning of the First Amendment.”

That the First Amendment should be so tested just seven years after its ratification in 1791 may seem odd, but those in power did not interpret the law as we do now The Federalists who supported the Sedition Act had a narrow view of freedom of the press, a perspective that likely stemmed as much from political expediency as from principle. The Federalists argued that the First Amendment meant nothing more than it did under English common law, which protected the press from prior restraints on publication but not from punishment for calumnies against the government after publication.

The Sedition Act spurred James Madison to articulate a much broader conception of press freedom. In his Report of 1800 on the Virginia Resolutions, Madison argued that an American understanding of freedom of the press had to flow from the Constitution’s placement of sovereignty in the people, rather than in the government in the British system. From popular sovereignty, he argued, “a different degree of freedom in the use of the press should be contemplated.” The press had a central role in holding public officials accountable to the people—what Madison described as “that right of freely examining public characters and measures, and of free communication among the people thereon, which has ever been justly deemed the only effectual guardian of every other right.”

Madison’s view of the First Amendment eventually won the day. And it was Benjamin Franklin Bache and a group of rowdy journalists in the waning days of the eighteenth century who instigated the battle that helped define freedom of the press in America’s republic form of government.

Benjamin Franklin Bache and the Fight for the Free Press

By Ronald K.L. Collins, former Harold S. Shefelman Scholar at the University of Washington Law School, and author of Nuanced Absolutism: Floyd Abrams and the First Amendment. Collins now edits a weekly blog called First Amendment News, and serves as the co-director of the History Book Festival.

Part I.

There is now only wanting … a sedition bill, which we shall certainly soon see proposed. The object of that is the suppression of the Whig presses. Bache’s [Aurora] has been particularly named. — Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, April 26, 1798

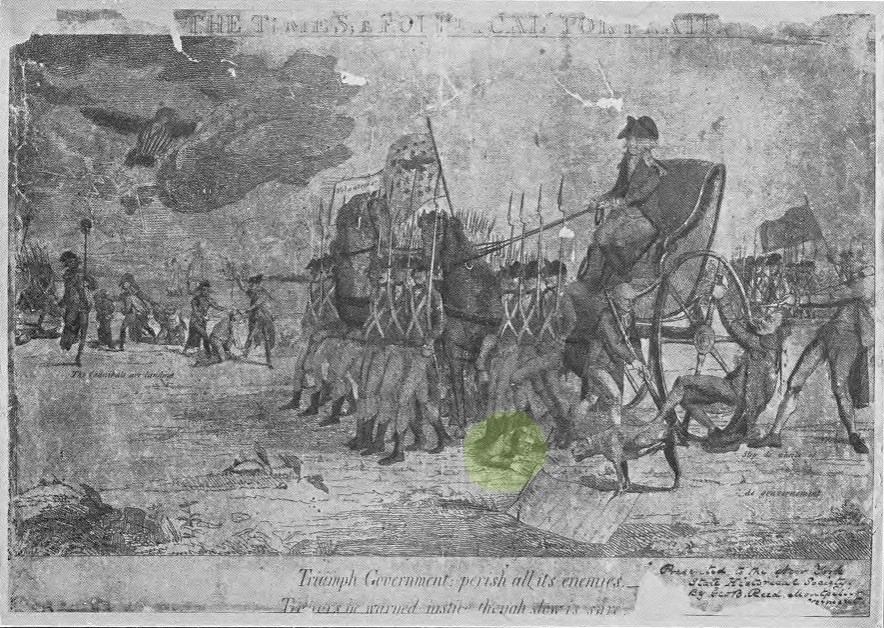

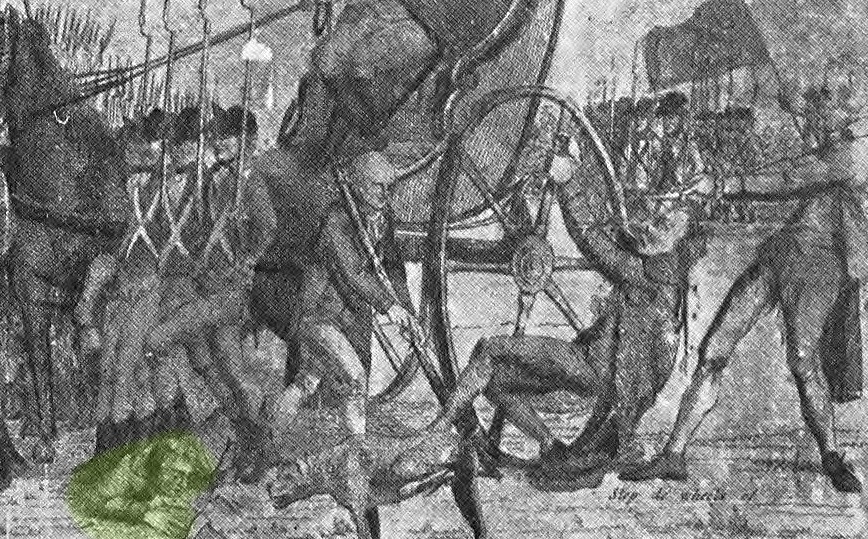

Within the walls of the New York Historical Society there is a remarkable caricature of political strife in America circa 1798. Appearing in The Times: A Political Portrait, this drawing depicts President John Adams in regal military garb leading the carriage of state while James Madison pokes his long and powerful pen into one of its wheels — this while a determined Thomas Jefferson pushes mightily to stop the carriage of state. Meanwhile, a band of marching Federalist soldiers tramples Benjamin Bache, a Jeffersonian journalist. And then a final insult: A mangy dog lifts its leg over Bache’s paper, the Aurora.

Close up of the political cartoon “The Times: A Political Portrait.” Highlighted in yellow on the bottom left is Benjamin Franklin Bache, crushed by the weight of Washington’s carriage. The artist also drew a dog (middle) peeing on Bache’s newspaper the Aurora. (New-York Historical Society)

Acerbic, caustic, vile, vituperative, uncontrollable, scurrilous, and often mean-spirited — this was the trend of the times in 1790s America. The Federalist and anti-Federalist printers and newspaper editors of that time tested the fiber of the First Amendment like no one since. So much so, that no treatment of that guarantee can be complete without some serious discussion of one of its most colorful figures, Benjamin Franklin Bache (1769-1798).

One must look long and hard to find much more than fleeting references to Bache, if that, in many of the major works on the First Amendment. He is an unknown in law school casebooks and treatises, a nameless nobody in numerous journalism texts, a missing person in political science books, and a figure of slight notice in many volumes of American history, though there are a few notable exceptions.

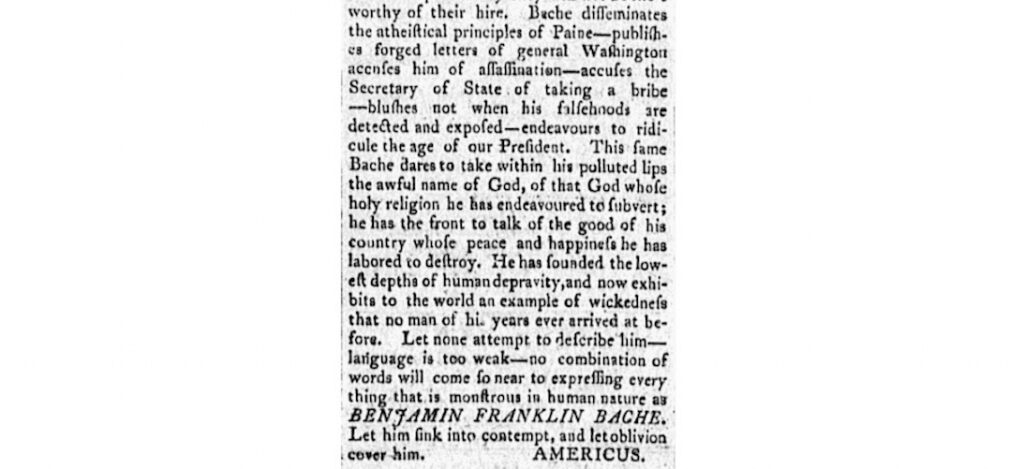

Hero or heretic? By and large, it is as if the railings of the old Federalist rag, John Ward Fenno’s Gazette of the United States (May 11, 1798), had cursed Bache’s fate forever: “Let none attempt to describe him — language is too weak — no combination of words will come so near to expressing everything that is monstrous in human nature as BENJAMIN FRANKLIN BACHE. Let him sink into contempt, and let oblivion cover him.”

Foe of George Washington and John and Abigail Adams and friend of Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, this grandson of Benjamin Franklin was an anti-Federalist crusader at a time when the prosecutorial winds blew strong against “sedition.” When Bache died at age 29 on Sept. 10, 1798, the Republican-spirited Independent Chronicle (Sept. 17, 1798) hailed him: “The real friends of [our] country cannot but lament the loss of so valuable a citizen.” Years later, in 1811, Jefferson wrote to his lawyer friend William Wirt about the importance of Bache’s Aurora: “It was our comfort in the gloomiest days.” Jefferson deemed this kind of “watchful sentinel” as crucial for constitutional government in America.

Whatever one may make of this firebrand pamphleteer and printer of the Aurora, Bache’s story reveals much about the birth of political suppression in the new nation and the spirited response to that oppression. It is, to be sure, a complicated history, but nonetheless noteworthy in its record of the struggle for freedom of the press at a time when the First Amendment was first tested — with vicious vigor.

Franklin’s imprint. Benjamin Franklin was the wind beneath Benjamin Bache’s wings. It was his famous grandfather, more than his father Richard or his mother Sarah, who most shaped the philosophical and professional life of the young Bache. At age 7 the boy ventured to faraway France to the court of Louis XVI; his grandfather was America’s ambassador. There he attended French boarding schools and played with John Quincy Adams until Franklin sent him off to Geneva with a Swiss diplomat, Philibert Cramer, one of Voltaire’s publishers. The boy learned French, Latin, and Greek and took much joy in the ways of Enlightenment education. In 1782, Benny Bache returned to France where he took up the “fine art” of printing in Passy. In time, he worked as an apprentice to some of the most noted printers in France.

Around that time, Benjamin Franklin counseled moderation in publishing, stressing that an editor should “consider himself as in some degree the Guardian of his Country’s Reputation, and refuse to insert such Writings as may hurt it.” At first, that gospel sat well with the European-educated lad, who nonetheless hated any form of monarchy or oligarchy.

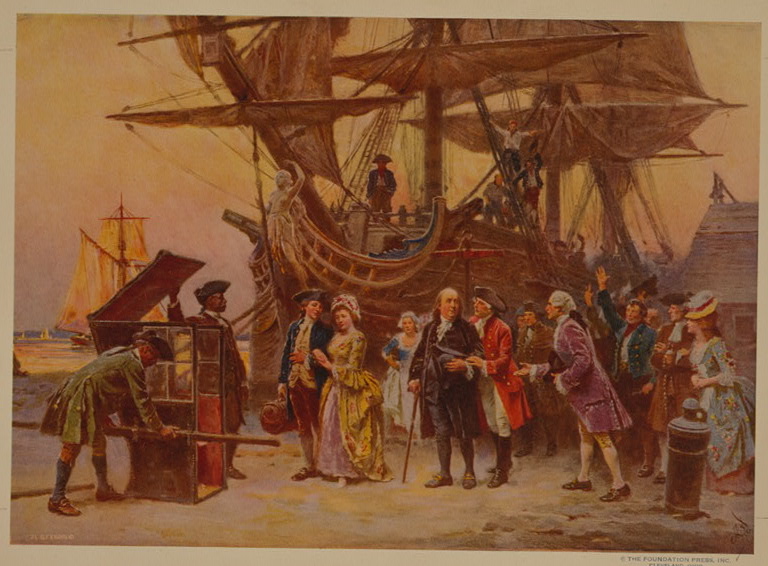

When Franklin and his grandson returned to Philadelphia in mid-September 1785, the revered statesman was greeted with wild enthusiasm and thunderous cannon fire. In that glorified atmosphere, Bache enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, still determined to be a printer. After a few years, he took his Bachelor of Arts degree, though his graduation was delayed by meetings of the Constitutional Convention, which were held nearby.

Benjamin Franklin (center, in red) and his grandson Benjamin Franklin Bache (to the left, in blue) return to Philadelphia from Europe, where Bache was educated. (Library of Congress)

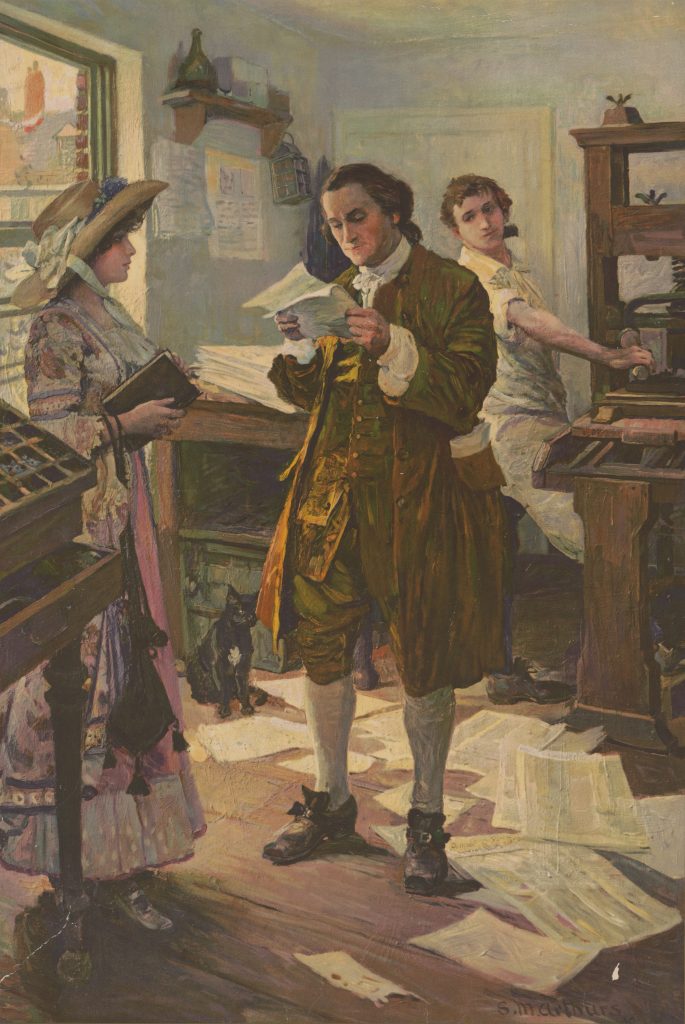

Benjamin Bache depicted in the background of an image of Benjamin Franklin in his Philadelphia printing shop. Painting by Arthurs, S.M, unknown date. (Library of Congress)

With Franklin’s encouragement and capital, Bache became a Philadelphia printer, at first printing and selling Greek and Latin grammar books along with books for children. By the time his famous and wealthy grandfather died in 1790, the 21-year-old Bache was ready to enter into the political fray and publish his own newspaper. In a prospectus for the paper he released at the time, Bache declared: “This Paper will always be open, for the discussion of political, or any other interesting subjects, to such as deliver their sentiments with temper & decency, and whose motive appears to be … the public good.”

It was a noble intent, one expressed at just the time when political conflict was starting to be the coin of America. And that conflict worked its ways into the bones of Benny Bache, who became less serene and more outraged as the 1790s unfolded. Soon enough his philosophical detachment gave way to partisan protests.

‘Jeffersonian journalism’ vs. Federalist favoritism. In Colonial times and thereafter, there was a certain faith in the printed word and in the rough-and-tumble of divergent views. This reflected the old Miltonian belief in the staying power of truth and in men’s ability to discern it. Benjamin Franklin, the onetime editor of the Pennsylvania Gazette, held dearly to that sentiment. As early as June 10, 1731, he wrote the following in the Gazette: “Printers are educated in the belief that even when men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick; and that even when Truth and Error have fair play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter.”

As politics collided with principle in the 1790s, the nation was hopelessly divided and confidence in a free exchange of ideas began to wane. In those days one either sided with the presidential administration (Washington, Adams, Hamilton and the like) or opposed it (Jefferson, Madison, Paine and the like). One either hated France and prepared for war against it (Federalists) or admired its egalitarian resolve and tried to maintain peace (anti-Federalists). One either supported calls for a greatly expanded federal army (Hamilton) or opposed them (Jefferson).

The newspapers of the day mirrored this stark dualism of views, this at a time when public interest in the press increased greatly. “During the 1790s,” as author Ron Chernow has written, “the number of American newspapers more than doubled.” And of those, he added, “many partisan sheets specialized in vituperative character attacks.”

“Printers are educated in the belief that even when men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick; and that even when Truth and Error have fair play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter,” Franklin (1731).

On the Federalist side, there were papers like John Fenno’s Gazette of the United States and William Cobbett’s Porcupine’s Gazette. On the anti-Federalist side, there were the likes of the Boston Independent Chronicle and Benjamin Bache’s General Advertiser, Commercial, Agricultural, and Literary Journal, which later came to be known as the General Advertiser or simply the Aurora. (Some years later, Matthew Lyon, a Vermont congressman, published The Scourge of Aristocracy and Repository of Important Political Truths — a radical Jeffersonian Republican newspaper dedicated to opposing Federalist publications that “vomit[ed] forth columns of lies.”)

The arrival of the Aurora. When Benny Bache’s paper came on the scene on October 1, 1790, a graphic of the Aurora borealis appeared on its nameplate. It was “just as [Benjamin] Franklin had represented the phenomenon, with luminous electrical rays emanating through the earth’s atmosphere.” Below the word “Aurora,” Jeffrey A. Smith has also noted, was the motto: “SURGO UT PROSIM” — “I rise to be useful.” For $5.00 a year one could receive Bache’s commercial and political messages six days a week. The paper’s circulation began at around 400 and increased to an impressive 1,700 within a few years.

A writer calling himself “Americus” calls Bache wicked and claims the printer has “labored to destroy” his country.

Soon enough Bache had a nickname in Philadelphia circles and elsewhere — “Lightning Rod Junior.” He was so called, observed James MacGregor Burns, “because he was the grandson of Benjamin Franklin and liked to apply electric shocks to the Federalists.” Such officials and Federalist-supported causes quickly became targets in Bache’s editorial crosshairs. For example:

- The Aurora joined ranks with tradesmen, manufacturers, and farmers in the fierce battle over excise taxes.

- The Aurora led the charge against the Jay Treaty when it disclosed its contents after the senate approved it but before President Washington signed it and made its terms public.

- Soon afterwards, Bache reprinted the entire document in a pamphlet and then ventured to New York, Boston, and elsewhere to distribute it, hoping to spawn opposition to it.

- Much ink was spent on Alexander Hamilton, the Federalist bogyman for many Jeffersonian Republicans. “By some it is whispered,” Bache wrote in the Aurora on November 8, 1794, “that he is with the army without invitation and by many it is shrewdly suspected his conduct is a first step towards a deep laid scheme, not for the promotion of the country’s prosperity, but [for] the advancement of his private interests.”

- The anti-Federalist attacks against George Washington were as harsh as they were commonplace. After the president had signed the Jay Treaty — Bache wrote that many “cannot yet believe it” — citizens were warned to be on the alert against being “lulled … into a dangerous security by the arts of those whose interest is to deceive them.”

- And in “the year before the election of 1796,” Jeffrey Smith has observed, the Aurora was chock full “with regular reminders that Washington was a slaveholder and . . . that he was servile to Britain and hostile to France.”

The “infamous scribblers,” as Washington branded them in late June of 1796, were relentless in their criticisms of his second term. Finally, he could take it no more; in a momentous move Washington declined to pursue a third term — this though “many Americans expected him to serve for life,” as Chernow has noted.

The ink on his Hamilton-inspired farewell address was hardly dry when the anti-Federalists lashed out at old George Washington. Thus, as recorded by Joseph Ellis, Bache gave prominent attention to Tom Paine’s anti-Washington rants. In a letter published in the Aurora, Paine wrote: “[T]he world will be puzzled to decide whether you are an apostate or an imposter, whether you have abandoned good principles or whether you ever had any.”

Bache agreed, entirely. In his eyes, Washington’s retirement was a splendid occasion: “If ever there was a period for rejoicing,” the Aurora proclaimed (March 6, 1797), “this is the moment — every heart, in unison with the freedom and happiness of the people, ought to beat high with exultation that the name of WASHINGTON from this day ceases to give currency to political inequity and to legalize corruption . . . .”

Typical Bache, thought John Fenno, editor of the Gazette of the United States, a Federalist-sympathetic paper. “Mr. Bache . . . seems to take a kind of hellish pleasure in defaming the name of WASHINGTON. (March 7, 1797)

As for George Washington, he had had it with this contemptible printer: His “Calumnies are to be exceeded only by his IMPRUDENCE, and both stand unrivaled,” he complained to Jeremiah Wadsworth in a March 6, 1797 letter.

But Bache’s editorial arrows were not limited to Hamilton and Washington. For like his grandfather, the young Bache held strong views about John Adams. On the one hand, the elder Franklin granted that Adams was “always an honest man,” as he told Robert Livingston in late July of 1783. And he conceded that Adams was “often a wise” man, too. On the other hand, “sometimes, stressed Franklin, he is “absolutely out of his senses.” That sentiment held strong with Benny Bache — in the 1790s it turned to outright animosity, expressed unabashedly, openly, and frequently.

“Old, querulous, Bald, blind, crippled, Toothless Adams” is how the editor of the Aurora described the president he loved to loathe. For Mrs. Adams, she hoped and prayed that “the wrath” of the people would one day “devour” this “lying wretch of a Bache.”

The war of words was escalating; it quickly became a fight for freedom itself.

An image of Aurora‘s nameplate, which included a graphic of the aurora borealis and the Latin motto “SURGO UT PROSIM,” meaning “I rise to be useful.”

Part II.

It was well known that Abigail Adams despised Benjamin Bache. By her moral compass, he was vile and treacherous. Or as she once confided to her sister, Mary Cranch: “Scarcely a day passes but some such scurrility appears in Bache’s paper, very often unnoticed, and of no consequence in the minds of many people, but it has, like vice of every kind, a tendency to corrupt the morals of common people. Lawless principles,” she emphasized, “naturally produce lawless actions.”

Abigail Adams, spouse of President John Adams, frequently dismissed Bache’s paper as immoral. (National Portrait Gallery)

Bache’s tirades against the Administration and Federalist lawmakers also made him a persona non gratis in Congress. In 1797, for example, he was punished for his all-too-uninhibited and critical accounts of its proceedings. For this, he was banned from the House floor for the entire 1797-1798 session of Congress. This “act of tyranny,” as Bache labeled it in a pamphlet titled Truth Will Out!, kept a “free and firm statement of the [House’s] proceedings” from the public attention.

Bache likewise suffered physical attacks; he was assaulted in the streets. Federalist mobs likewise attacked his home, causing property damage and prompting personal fear. Similarly, Federalist advertisers withdrew their ads in the Aurora, which hurt him financially. So far as the Federalists were concerned, there seemed to be no punishment too severe to inflict upon the Philadelphia printer. William Cobbett, the outspoken editor of Porcupine’s Gazette, urged that Bache be treated as “a TURK, A JEW, A JACOBIAN, OR A DOG.” (March 17, 1798).

Federalist Congressman John Aller of Connecticut viewed Benjamin Bache’s actions through a legal lens: The Aurora was “the great engine of all . . . treasonable combinations.” What Bache had printed, Aller continued, was tantamount to “a conspiracy against the Constitution, the Government, [and] the peace and safety of this country . . . .” Mrs. Adams agreed. She urged that Bache be “prosecuted” for his “libels upon the President and Congress.” His “wicked and base” abuses, she declared in letters penned between March and May of 1798, ought to be “Presented [to] grand jurors.”

Benny Bache’s star was falling. The worse things got for the intemperate newspaper publisher, the more vengeful his critics became. Still, his printing press rolled on day after day, wrecking ever more havoc for his Federalist foes.

Fighting faith

The fires were fanned to the heavens when in early April of 1798 the Aurora took aim at Alexander Hamilton for the XYZ Affair, which involved explosive communiqués from American envoys about failed diplomatic talks with French officials. According to Chernow, about this time “President Adams made a politic speech to Congress that announced that the mission had foundered while omitting the notorious circumstances,” which included French demands for loans and even personal bribes. Of course, such humiliating disclosures “would have riled the public.”

A British satirical cartoon depicting Franco-American relations after the XYZ Affair. Five Frenchmen plunder female “America,” while five figures representing other European countries look on. (Library of Congress)

The Aurora implied that the debacle was somehow Hamilton’s fault since he was a friend of the corrupt French minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord. “Mr. Talleyrand is notoriously anti-republican. . . . [H]e was the intimate friend of Mr. Hamilton . . . and other great Federalists, and . . . it is probably owing to the determined hostility which he discovered in them towards France that the government of that country considers us only as an object of plunder.” It was, to say the least, a bold (even irresponsible) charge.

Hamilton did not take kindly to the Aurora’s broadsides – he responded with a seven-part newspaper series titled “The Stand.” Abigail Adams was equally incensed. The “language in Bache’s paper,” she wrote to her sister on April 7, 1798, “has been of the most insolent and abusive kind . . . .”

Against this backdrop, the Federalists intensified their campaign to persuade advertisers to withdraw their advertisements from Republican papers, especially the Aurora. The tactic took its toll on Bache and others. At this time he was nearly bankrupt and had to spend over $15,000 to save the Aurora. Worse still, his wife Margaret was pregnant with their fourth child. But no ill fate would silence Bache . . . though more bad luck was headed his way.

In late April of that year, a worried Thomas Jefferson penned a note to James Madison about the Federalist campaign to ruin Republican papers like Bache’s Aurora and Matthew Carey’s United States Recorder: “We should really exert ourselves to procure [subscriptions] for them, for if these papers fall, Republicanism will be entirely browbeaten.”

Despite all of this, Bache continued on and on, taking ever deadlier aim at his critics, especially the monarchial minded Adams. Incredibly, there was a measure of truth in such attacks. For about this time John Adams seemed eager to seize the reigns of kingly power. “America must resort,” Adams wrote to Benjamin Rush on June 9, 1789, to “hereditary Monarchy or Aristocracy . . . as an asylum during discord, Seditions and Civil War.”

Time was about to march backwards. Bache had warned often of this possibility. Fearful of such things and others, rumors arose that the citizens and militia of Virginia had armed themselves in preparation for a clash with Federalist soldiers. Things ratcheted up on all fronts. Meanwhile, boatloads of “would-be citizens” left America fearing prosecution under the newly enacted Alien Law – another Federalist device to end “sedition.”

Things got worse: On June 16, 1798, Bache published a secret state communication before Congress had even seen a copy of it from President Adams. The banner for that day’s issue of the Aurora read: “We hasten to communicate to our Readers the following very IMPORTANT STATE PAPER From the French Minister of Foreign Affairs to the American Commissioners.” The document was a self-serving letter from Talleyrand to the American envoys stationed in France. It gave the misleading impression of a conciliatory attitude, of a willingness to settle differences between France and America. “Bache defended his publication of the ‘scoop,’” James Smith has observed, “on the ground that the administration was withholding it in an effort to embroil the United States in an unnecessary war with France.” When the Federalist editor of the Porcupine got wind of this, he lashed out in print against the “prostitute printer” who had printed the secret document for the “express purpose of . . . exciting discontents . . . and to procure a fatal delay of preparation for war.”

Benjamin Franklin Bache’s decision to publish a secret communication between a French minister and President John Adams intensified Federalist hatred towards him, ultimately leading to his imprisonment under the Sedition Act of 1798. (Wikimedia Commons)

Benjamin Bache should be “seized” immediately, said Mrs. Adams. Alas, he had gone too far; he had crossed a line. Worse still:

- He had knowingly sided with the treacherous French;

- he had unfairly blamed the honorable Washington;

- he had shamelessly abused President Adams;

- he had unjustly maligned Hamilton;

- he had fiercely disparaged and mocked members of Congress;

- he had maliciously printed state secrets;

- and in the process of it all, he had willfully created animosity in the people against their Federalist leaders.

Or so the complaints went. Something had to be done, the Federalists declared, to stop the seditious likes of Bache et al. And so later in the summer of 1798, John Adams signed the infamous Sedition Act, which made it criminal to “write, print, utter, or publish” any “false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either House of the Congress of the United States, or of the President of the United States” with “intent to defame” any such parties or to bring them “into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them . . . the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to stir up sedition within the United States; or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States . . . .” The sanctions: “a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and . . . imprisonment not exceeding two years.”

Unwilling to wait for the signing of the bill into law on July 14, 1798, Federalist prosecutors hauled Bache off to court on June 26th and charged him with violating the federal common law of seditious libel, this for “libeling the President & the Executive Government, in a manner tending to excite sedition, and opposition to the laws, by sundry publications and re-publications.” Among other things, the defense challenged the jurisdiction of the court. Because of that, the matter had to be assigned to another judge, which meant some delay. Pending a trial at the October term of the court, bail was set at $4,000, an amount Bache could hardly afford in his current state of economic woe.

At last, the “seditious printer” had been arrested; now his “scurrilous rants” would cease. But things did not play out that way – the day after his arrest Bache vowed in the Aurora never to abandon “the cause of truth and republicanism,” which he pledged to honor to “the best of his abilities, while life remains.”

The “American plague”

Had it just been financial and political woes, and fears of a criminal conviction, Benny Bache may have survived the wrath of his adversaries. But there was one enemy he could never defeat – yellow fever, aka the “American plague.” As James Tagg described it: “The fifth yellow fever plague of the decade, one which would kill over 3,500 persons in Philadelphia, was dreadful by its repetition alone. Victims, jaundiced and weakened from vomiting,” he noted, “were often abandoned and sometimes even found lying delirious in the streets. Businesses closed, people fled, and crime increased.”

“A PRESSMAN WANTED AT the OFFICE of the AURORA.”

That call for help ran on the Aurora’s front page on September 4, 1798. Things quickly became desperate as the deadly fact of the plague became obvious. “ONE HUNDRED and TWENTY-SEVEN new cases of the prevailing fever were reported for the last 24 hours by eighteen physicians.” That Aurora news item in the September 8, 1798 issue made it plain that Philadelphia was being ravished by the “black vomit plague,” as it was sometimes tagged. Yet, Benjamin Bache and his family remained.

Predictably, the fate of the fever caught up with him. Shortly after his fourth child was born, Benjamin Bache met his maker. Late on the evening of Monday, September 10, 1798, he died, with a French physician attending him, no less. Miraculously, his wife survived.

Before “his corpse was cold,” Cobbett later noted in the Porcupine Gazette (May 1, 1799), Margaret Bache “hawked about the city” with a boldly-worded printed notice of his death. It read:

“The friends of civil liberty and patrons of the Aurora are informed that the Editor, BENJAMIN FRANKLIN BACHE, has fallen victim to the plague . . . . In ordinary times the loss of such a man would be a source of public sorrow – in these times men who see, and think, and feel for their country and posterity can alone appreciate the loss – the loss of a man inflexible in virtue, unappalled by power or persecution – and who in dying knew no anxieties but what were excited by his apprehensions for his country – and for his young family.”

John Adams disagreed, strongly: “[T]he yellow fever arrested” this “malicious libeler” in his “detestable career and sent him to his grandfather, from whom he inherited a dirty, envious, jealous, and revengeful spite against me.” So he told Benjamin Rush years later.

As for William Cobbett, “‘AN ELEGY ON BACHE’ cannot appear in my paper,” he wrote in the Porcupine Gazette on September 19, 1798. “A Briton scorns to mangle the carcass which he himself has slain,” he added, “and much more, one that has been slain by the ALMIGHTY.”

With Bache dead, the Aurora’s presses still, and the Adams Administration armed with a new law to silence its political enemies, the anti-Federalists had good cause to fear their fate. The Alien and Sedition Acts, Vice President Jefferson warned Senator Stevens Thompson Mason in an October 11, 1798 letter, were “merely an experiment on the American mind to see how far it will bear an avowed violation of the Constitution.” So what would become of this “experiment” in constitutional government?

The tide changes

Despite the gloomy prospects for Jeffersonian sympathizers, Margaret Bache resumed a robust publication of the Aurora on November 1, 1798, this with the aid of Bache’s assistant, William Duane – the same man who had once been deported from India for lambasting East India Company officials while editor of a Calcutta paper. He was every bit as fiery an editor as Benny Bache, perhaps even more so.

“In the next two years, [Duane] managed to overcome indictments for sedition,” notes Jeffrey A. Smith. Nonetheless, he “was mobbed and beaten by federal troops he had criticized.” As if that were not enough, Duane was also “menaced with deportation by Secretary of State Timothy Pickering.” Later, he “was forced into hiding for a time after being found guilty of contempt of the Senate.” In 1800, Margaret Bache and William Duane married; the two thereafter continued to publish the paper, which Duane edited until 1822.

Relief finally came to the Republicans. Thomas Jefferson prevailed in the election of 1800 and pardoned those convicted under the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Sedition Act expired on March 3, 1801. The spirit of the First Amendment had returned like a great Phoenix.

As for Bache’s Federalist counterparts: John Fenno, editor of the Gazette of the United States, died of yellow fever a mere four days after the plague claimed Bache’s life. And not long afterward, in 1799, William Cobbett’s Porcupine Gazette printed its last pages. With the Republican victory, a disillusioned Cobbett returned to his motherland, England. Ironically, years later, in June of 1810, he was found guilty of treasonous libel and sentenced to two years imprisonment in the infamous Newgate Prison.

It was over. All that remained was history and how the writing of it would treat Bache’s legacy, which Margaret Blanchard summed up this way: “[H]e showed, very early in the history of the United States, how far freedom of the press could be extended and how fragile that freedom could be.” In attempting to exercise that freedom he won the praise of some and the condemnation of others. Bache’s life in print is thus as good as any example of just how great a price a tolerant people must pay to be free.

Thus ends this short story of Benjamin Franklin Bache, an American printer and pamphleteer like no other.

* * *

So what is the takeaway? What should we make of Benjamin Bache and his Aurora? The easy answer is to hail him as a First Amendment hero. But that answer is to take historical context out of the normative equation. Remember: In those days the American world was badly divided between Bache’s Aurora and Cobbett’s Porcupine Gazette, between the Anti-Federalists and the Federalists, between Jefferson and Adams. Sound familiar? – Fox News vs MSNBC, Republican vs Democrat, Trump vs Pelosi. Of course, in modern America dissidents like Bache are not prosecuted, however much any president might wish it. And that’s where the law and the culture of the First Amendment come into focus.

If the American experiment in free speech freedom is to succeed, those on each side of the ideological divide must at some point pause and allow that which they abhor to have its say in the marketplace. Risky? Perhaps. Then again, that’s the price one pays for experimenting with liberty. “Every year, if not every day,” Holmes reminded us, “we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge.” Take heed.

I gladly recognize my reliance on James Tagg’s comprehensive biography of Benjamin Bache, on Daniel Green’s resourceful biography of William Cobbett, on James Morton Smith’s invaluable work on the Alien and Sedition laws, on Eric Burns’ helpful Infamous Scribblers, on Jeffrey Smith’s compact but informative Franklin and Bache, and on Richard Rosenfeld’s indispensable American Aurora, all cited below. Benjamin F. Bache’s papers are located at the American Philosophical Society Library in Philadelphia. Portions of these two essays on Bache were written ages ago when I worked for the First Amendment Center, so a nod to my then bosses and colleagues Ken Paulson and Paul McMasters is in order.

Sources

Arthur Scherr, “Inventing the Patriot President: Bache’s Aurora and John Adams,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1995) 119 (4): 369-399.

Bache, Benjamin Franklin. Truth Will Out! The Foul Charges of the Tories Against the Editor of the Aurora Repelled by Positive Truth and His Base Calumniators Put to Shame. Philadelphia, PA: 1798 (Kessinger publishing reprint).

Bailyn, Bernard and John B. Hench, eds. The Press and the American Revolution. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1980.

Belt, Gordon T. “The First Amendment in the Colonial newspaper press”

Bernard Fay, The Two Franklins: Fathers of American Democracy (Little, Brown, 1933

Beveridge, Albert J. The Life of John Marshall, vols. II & III Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1919.

Blanchard, Margaret A. “Benjamin Franklin Bache,” in Dictionary of Literary Biography, vol. 43, pp. 41-21 (a useful overview)

Brant, Irving. The Bill of Rights: Its Origin and Meaning. N.Y: The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1965.

Burns, Eric. Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism. N.Y.: Public Affairs, 2006.

Raffi Andonian, “The Adamant Patriot: Benjamin Franklin Bache as Leader of the Opposition Press,” Penn State University Libraries (n.d.)

Burns, James MacGregor. The Vineyard of Liberty: The American Experiment. N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982.

Ckernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. N.Y.: Penguin Books, 2004.

Cogan, Neil H., ed. The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins. N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Ellis, Joseph J. Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. N.Y.: Vintage, 2002.

Fay, Bernard. The Two Franklins: Fathers of American Democracy. Boston: Little Brown, 1933)

Green, Daniel. Great Cobbett: The Noblest Agitator. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1983.

Hall, Kermit L. The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992 (David M. Rabban entry re “Bad Tendency Test”).

Hogan, Margaret A., & Taylor, C. James. My Dearest Friend: Letters of Abigail and John Adams. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2007.

Ingrams, Richard. The Life and Adventures of William Cobbett. N.Y: HarperCollins, 2005.

James MacGregor Burns, The Vineyard of Liberty (Knopf, 1982)

James Morton Smith, Freedom’s Fretters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties. Ithaca (Cornell University Press, 1956)

James Tagg, Benjamin Franklin Bache and the Philadelphia “Aurora” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991)

Jeffrey A. Smith, Printers and Press Freedom: The Ideology of Early American Journalism Printers and Press Freedom: The Ideology of Early American Journalism (Oxford University Press, 1987)

Kaye, Harvey J. Thomas Paine and the Promise of America. N.Y.: Hill and Wang, 2005.

Keane, John. Tom Paine: A Political Life. N.Y: Grove Press, 1995.

Levy, Leonard W. Emergence of a Free Press. N.Y: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Martin Gruberg, “Benjamin Franklin Bache,” The First Amendment Encyclopedia (n.d.)

McCullough, David. John Adams. N.Y., Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Merrill D. Peterson, ed. Thomas Jefferson: Writings ( Library of America, 1984)

Nattrass, Leonora. William Cobbett: The Politics of Style. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Pasley, Jeffrey L. The Tyranny of Printers: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001.

Richard N. Rosenfeld, American Aurora: A Democratic-Republican Returns (St. Martin’s Press, 1997)

Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (Penguin Press, 2010)

Rosenfeld, Richard N. American Aurora: A Democratic-Republican Returns. N.Y: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Smith, James Morton. Freedom’s Fetters: The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1956.

Smith, Jeffrey A. Franklin & Bache: Envisioning the Enlightened Republic. N.Y: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Stephen Solomon, Revolutionary Dissent: How the Founding Generation Created the Freedom of Speech (St. Martin’s Press, 2016)

Stewart, Donald H. The Opposition Press of the Federalist Period. (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1969)

Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime From the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism. N.Y: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

Tagg, James. Benjamin Franklin Bache and the Philadelphia Aurora. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991.

_______. Franklin and Bache: Envisioning the Enlightened Republic (Oxford University Press, 1990)

_______. “The Limits of Republicanism: The Reverend Charles Nisbet, Benjamin Franklin Bache, and the French Revolution.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1988) 112 (4), 503-543.

_______. “‘Vox Populi’ versus the Patriot President: Benjamin Franklin Bache’s Philadelphia Aurora and John Adams (1797),” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies (Fall 1995) 62, No. 4 pp. 503-531

Tags