On December 5th, the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, the Brennan Center for Justice, and Simpson Thacher & Bartlett filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, challenging the U.S. State Department’s policy requiring all visa applicants to submit their social media handles.

The suit, filed on behalf of two documentary film organizations, argues that the registration requirement violates the First Amendment, is too broad in scope, and has not been proven to be necessary to national security interests.

“The Registration Requirement violates the expressive and associational rights of visa applicants by compelling them to facilitate the government’s access to what is effectively a live database of their personal, creative, and political activities online,” the complaint says.

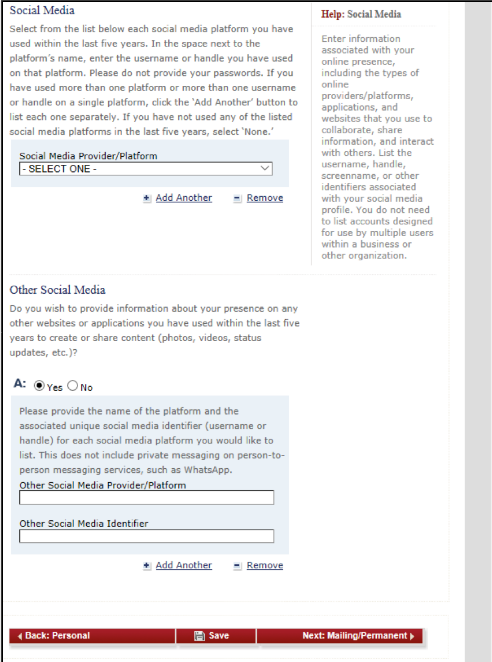

According to The New York Times, the State Department’s new policies went into effect in May, and affect more than 14 million applicants each year. The rules require applicants to register their social media handles–including pseudonyms–for 20 different online platforms.

The Registration Requirement as it appears on DS-260 Form. Screenshot taken from complaint.

Applicants’ social media identifiers go into a larger system of government records called the Alien File, Index, and National File Tracking System of Records. According to the complaint, the U.S. government uses this database to monitor visa applicants even after they enter the country. In some cases, the complaint notes, this information can be disclosed to other agencies, as well as to foreign governments.

While the plaintiffs admit that there may exist “circumstances in which the government could lawfully investigate specific visa applicants’ use of social media… a mandate that requires nearly all visa applicants to register their social media identifiers” represents an abuse of power.

The two documentary film organizations–Doc Society and the International Documentary Association–say the new rules have deterred filmmakers from participating in U.S. film festivals and sharing their art with U.S. audiences. Artists rely on social media to promote their work, connect with other filmmakers, and advocate for political and social causes.

“Concerned that their political views will be used against them during the visa process, [Plaintiffs’ non-U.S. members and partners] self-censor to avoid being associated with controversial ideas or sensitive topics.”

The federal government policy also poses unique concerns for filmmakers who use pseudonyms to conduct secretive research, or who rely on anonymity to “shield themselves or their families or associates from possible reprisals by state or private actors.”

Does the policy serve national security interests?

An article in the Columbia Journalism Review reported that the policy was first used by the Obama administration in 2015. After two years, the Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general found no evidence to indicate that the policy worked. But despite its reported ineffectiveness, President Donald Trump’s administration proposed expanding the policy.

“Previously, only about 65,000 visa applicants per year—those who had spent time in areas controlled by terrorist groups, for example—were asked to provide information about their social accounts. Now 14.7 million people per year—almost everyone who applies for a visa—must submit any handle they’ve used in the past five years,” CJR reported.

The State Department, headed by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, has defended the policy, arguing that it would help consular officers and federal agencies confirm the identities of visa applicants. But the complaint contests this, contending that the government has no evidence to explain the necessity of imposing it “on millions of visa applicants each year” nor “why the retention of visa applicants’ social media information beyond their visa eligibility determinations is necessary for those purposes.”

Complaint The New York Times Columbia School of Journalism

Tags