Black Lives Matter activist DeRay Mckesson has been involved in litigation for nearly eight years since a Louisiana police officer was reportedly struck in the head by a rock during a protest in Baton Rouge in July 2016. The officer sued Mckesson, claiming his involvement as an organizer in the protest made him liable.

The lawsuit against Mckesson, who told First Amendment Watch that he was not the organizer of the July 2016 protest, was filed in November 2016 by the officer, who was initially known as John Doe in court records but has since been identified as Officer John Ford.

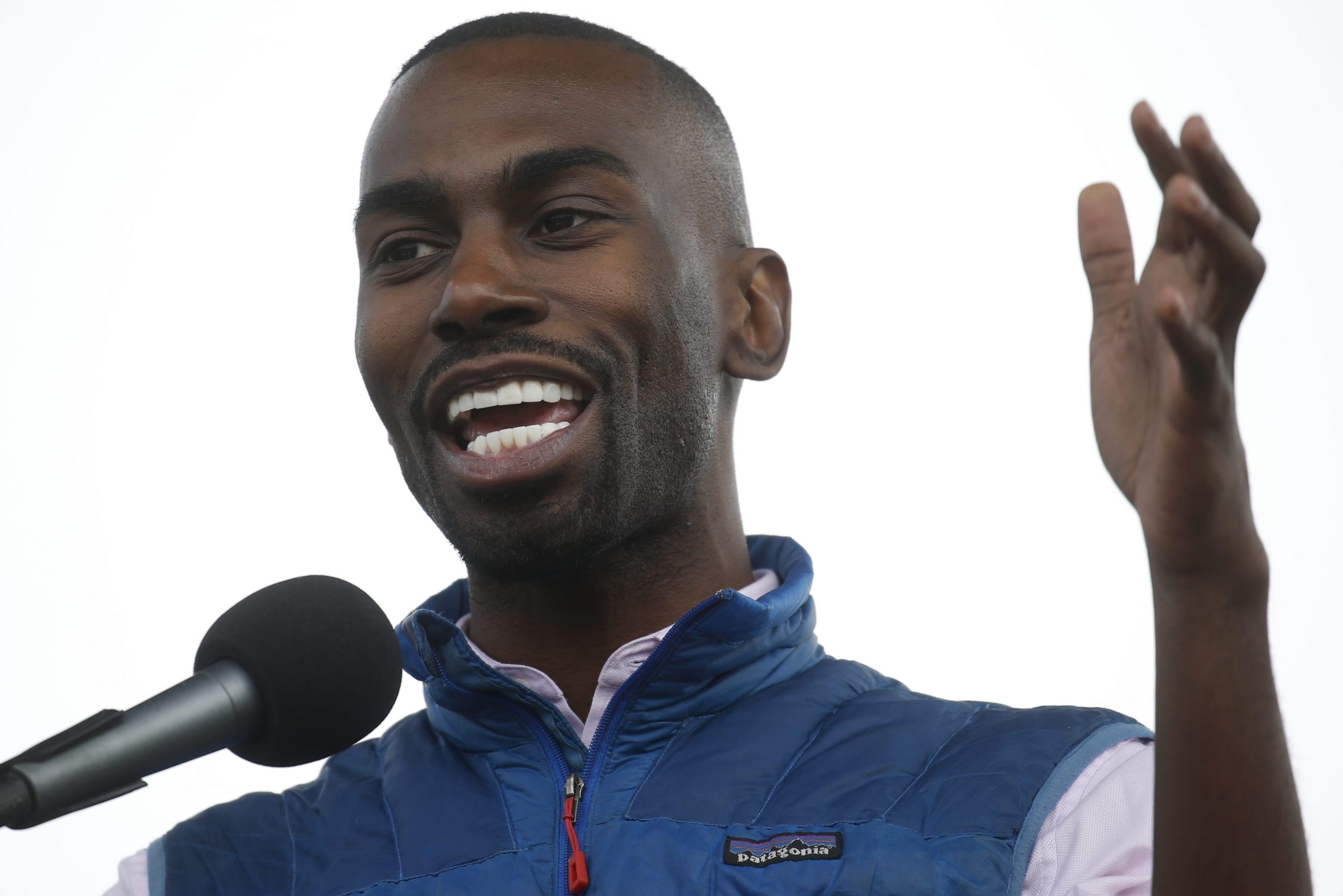

Civil rights activist DeRay Mckesson speaks during the “End Racism Rally” on the 50th anniversary of the assassination of civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on the National Mall in Washington, April 4, 2018. (Reuters/Leah Millis)

The protest, which began outside of the Baton Rouge Police Department on July 9, 2016, arose after the killing of Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old Black man, by a white police officer in Baton Rouge days earlier.

Ford’s lawsuit claimed that Black Lives Matter and Mckesson were responsible for his injury because Mckesson, according to the lawsuit, “incited the violence” and “was in charge of the protest.”

But a federal judge dismissed the lawsuit, stating that Black Lives Matter was not an entity that could be sued, and found that Mckesson “solely engaged in protected speech” during the protest. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reversed that decision, and Mckesson appealed to the Supreme Court which sent the case back to the Fifth Circuit for review if Mckesson, under state law, could be sued.

The Fifth Circuit then ruled in June 2023 that Mckesson’s involvement in organizing the protest meant that it’s “plausible that Mckesson knew or should have known” that a police response to the protest could lead to violence and injuries. It also rejected Mckesson’s claims that the First Amendment protects him from liability under state law.

Last month, the Supreme Court rejected another appeal from Mckesson in which Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted that the court’s “denial today expresses no view about the merits of Mckesson’s claim.”

The issue before the court was whether a protest leader or organizer could be held liable for any illegal or violent actions committed by protest attendees, despite a leader’s possible lack of knowledge of such actions.

First Amendment Watch spoke with Mckesson about the legal dispute. He described the day of the protest, rejected claims that he was an organizer of the demonstration, and expressed concern over the impact of his case on the right to protest.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

FAW: Can you tell me about the protest in which the officer was injured? How many people were in attendance? Were police on-scene at the start or did they arrive later?

DM: What has always surprised me about this case is that not only did I not organize that protest, but I was actually outside for very little time before I was arrested. So I got to Baton Rouge Friday night [July 8, 2016], I went to a meet up of people who were interested in ending police violence. Wake up the next day, we get something to eat. And then I go out to where the protests are. I’m probably outside for maybe two hours, it wasn’t long. And then I spent the next 17 hours in police custody. So when I got out [I thought] “it is what it is” and then I realized that I’ve been sued. So if you remember during that time, there were police officers in Dallas who got killed, it was like all during the same sort of window. So I got sued by one of [the Dallas officers’] family members for their death. And then I got sued by officers in Baton Rouge sort of all in the same weeks. And we got all of those cases dismissed, which was great. In this case, the officer appealed and we lost on appeal and I’ve been dealing with that ever since.

FAW: As you mentioned, the amount of time you spent at the protest was limited. While you were there, was it peaceful? Did you make any attempt to keep the peace as an attendee, rather than an organizer?

DM: Yeah, it was incredibly peaceful and the only people I saw engaged in violence were the police. They were engaging in snatch-and-grabs and they were just like, pulling people. In Baton Rouge, it was very orderly, I guess is a way to say it. So the way those protests started is like the street wasn’t shut down. It was just like a lot of people outside. The police had cut off traffic but people weren’t standing in the street. They were standing on the median and the sidewalks. And they were sort of marching in the crosswalk. But there had been a lot of protests. This was not like “we shut down,” that just wasn’t going to happen. Later it progressed to what people would call a “traditional shutdown.” But the police had already shut down the highway, the police shut down the entire traffic in the entire area. I was arrested and that video went viral. I was live streaming on Twitter because I wanted people to see what was going on. I actually didn’t know I was arrested. I thought that I got caught in the stampede, like there were so many people that I fell, and I just couldn’t get up. So I was like, “Oh, I’m just stuck around people.” I didn’t realize it was two officers with their hands on my shirt. Like they were pushing me down. So I’m like, argh and I throw my phone. One of my friends here took the phone and then I spent the next 17 hours in jail. So it all happened very quickly. So that’s why I was surprised. And we alluded to this in our brief to the Supreme Court, but you know, there’s never been proof that there is a rock, that there’s an injury, that I’ve planned anything, and part of it is that the question became very quickly, can I be sued at all? So we never had a court hearing about the straight up facts of the case, because the legal question was, could you sue me at all and they had to take the police officer’s claims as true for the purpose of that question. So every question you have about the facts, I have about the facts.

Lone activist Ieshia Evans stands her ground while offering her hands for arrest as she is charged by riot police during a protest against police brutality outside the Baton Rouge Police Department in Louisiana, July 9, 2016. Evans, a 28-year-old Pennsylvania nurse and mother of one, traveled to Baton Rouge to protest against the shooting of Alton Sterling. Sterling was a 37-year-old black man and father of five, who was shot at close range by two white police officers. The shooting, captured on a multitude of cell phone videos, aggravated the unrest coursing through the United States in previous years over the use of excessive force by police, particularly against black men. (Reuters/Jonathan Bachman)

FAW: Lawyers for the officer struck by the rock urged the dismissal of your appeal on the grounds that the protest illegally blocked the highway and you did nothing to dissuade the violence that took place. How do you respond to that?

DM: The police stopped traffic on the highway, the protesters didn’t, I’m confused about all of it. We did not shut down the street. The police had already shut down the highway. I tweeted about the protests, definitely tweeted like where people were and to come and stuff like that, like I certainly amplified those messages and that was real, but there was no violence from the protesters to warn people about. That wasn’t a thing.

FAW: What is the next step following the denial of your appeal from the Supreme Court?

DM: We head back to district court, where the two main options are either they will dismiss the case, or we will actually have a jury trial.

FAW: Earlier in the case, the Supreme Court noted that the issue was “fraught with implications for First Amendment rights,” but in its April 15 rejection of your appeal, Justice Sonia Sotomayor stated that the court’s “denial today expresses no view about the merits of Mckesson’s claim.” What does this mean for your case? What did that feel like to have that validation but also the rejection happen simultaneously?

DM: Thank God for Sotomayor’s note. We read her note to make it virtually impossible for people to apply the Fifth Circuit’s decision in that case to any future cases. And that is a good thing. We would have liked for summary reversal, that would have been our goal, but we feel confident both in the historic Claiborne decision and in the Counterman decision combined to make it impossible to actually enforce the Fifth Circuit’s decision in our case. Now, what is unfortunate about the fact that they did not do summary reversal, is that I do think people have misread the decision and which is why you see the headlines being like you know, “the right to protest has ended” and people are alarmed. I’ve talked to organizers in the Fifth Circuit who are nervous and sort of unsure about what to do. If they had sent a clear signal and a reversal, I think that there would not be that. So the chilling effect of this is what we are nervous about, not the legal ramifications in practice.

FAW: As someone who is involved in protests, could the fear of liability affect future protest organizing? Do you think that your case could deter people from attending protests?

DM: This has been a long run for me personally. I’ve been doing this since 2016. The ACLU has made it clear that they’ll represent anybody who is sued using the Fifth Circuit decision, that they will represent them so that is a good thing. I hope that this does not make people afraid to protest.

More on First Amendment Watch: