The Newseum Institute’s First Amendment expert, Lata Nott, originally published this podcast on the Newseum blog, and has given First Amendment Watch permission to reprint.

Lata Nott, Executive Director of the Newseum Institute’s First Amendment Center

In this episode of The First Five, Lata Nott speaks with First Amendment expert and historian Stephen Solomon about symbolic speech, or nonverbal acts of expression, and to what extent they are considered protected speech under the First Amendment. Kneeling during the national anthem, burning the American flag, burning draft cards, hanging effigies of political leaders — these are all examples of symbolic speech used throughout American history. Solomon explains how government attempts to stifle controversial symbolic speech have fared, from colonial times to the present.

HOST

Lata Nott is executive director of the Newseum Institute’s First Amendment Center.

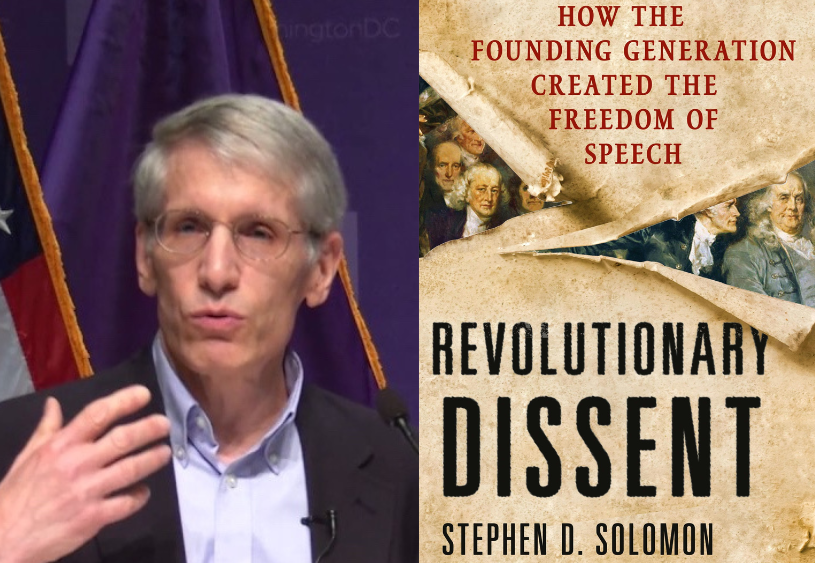

GUEST

Stephen Solomon

Stephen D. Solomon is associate director of NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute and author of “Revolutionary Dissent: How the Founding Generation Created the Freedom of Speech,” which explores the raucous history of free expression in America. Solomon is also the founding editor of First Amendment Watch, a website that tracks contemporary threats to the First Amendment.

READ MORE

TRANSCRIPT

LATA: Our topic today is symbolic speech, a concept that many people recently became acquainted with last year when NFL Colin Kaepernick, who played fro the 49ers in 2016 refused to stand for the National Anthem. He was protesting police violence against POC and his symbolic defense spread. Last year POTUS Trump encouraged owners to fire players that did so. This has spread to high school athletes as well. Does that 1st amendment protect this act? And how does taking a knee fit into the 1stAmendment?

My guest today is Stephen Solomon, he’s a professor at NYU’s Journalism Institute where he teaches First Amendment Law. He’s also the founding editor of the website First Amendment Watch whith provides a wonderful and comprehensive and constantly updated list of all the threats that are facing the first Amendment. He’s the author of the book “Revolutionary Descent: How the Founding Generation created Freedom of Speech” which is a fascinating exploration of freedom of expression in America’s founding period.

Stephen, thanks for being here.

STEPHEN: Thanks for having me.

LATA: It’s great to have an expert on this topic, especially since it’s captured the public’s attention in the past few months. So, right off the bat can we talk about symbolic speech?

STEPHEN: Certainly. This is something that is very basic to American history of protest and it goes way back, which we’ll discuss later on, but there are many ways to protest. People can write, people can speak, symbolic protest is very very powerful because it conveys a message that the Supreme Court said very aptly “conveys a message from mind to mind”. What they meant by that was that the clarity of the protest… you don’t have to read a long dissertation or newspaper article about the issue; when someone takes a knee or someone engages in any form of symbolic protest, it represents very clearly the issue and people understand that right away and so, you know, from mind to mind, the nature of the protest is passed and so it’s very effective.

It draws a lot of attention; which is part of the attraction for those who engage in this sort of expression. It draws attention and people sit up and take notice and it becomes – sometimes – very controversial.

Baltimore Ravens players kneel down during the playing of the U.S. national anthem before an NFL football game Sunday Sept. 24, 2017. Photo credit: Matt Dunham/Courtesy The Associated Press

LATA: I hadn’t thought of it that way. As opposed to passing out a pamphlet or making a speech, symbolic protest, as soon as you do it, people get it immediately. Taking a knee, burning a flag, burning anything, people immediately get what it is you’re saying.

STEPHEN: well there’s been a lot of protest; a lot of attention given to the issues that form the basis for Kaepernick’s protest. A lot has been written, a lot has been broadcast, but the taking of the knee comes to represent all of that – it’s all embodied in the symbolic act. It’s the same thing as burning a flag or burning a draft card during the Vietnam War – certainly was a lot written in opposition to the Vietnam War for years but then you have protesters burning draft cards and it draws attention, there’s clarity to it, you know, it becomes something that’s emblematic of the protest against the war itself.

LATA: why do you think this particular protest has touched such a nerve?

STEPHEN: I think there’s a number of things involved here. One has to go to the issues involved in a protest about the treatment of people of color by police in the community… which I think probably started all of this… and also it took place at an NFL football game which are very popular and they players took advantage of the fact that they had a large audience. Many of whom did not come for the protest, they came for the game. Also, taking a knee during the National Anthem is itself very controversial. The National Anthem and the flag have very and positive meanings to many many Americans. To in any way disfavor the flag, or protest the flag, or pledge of allegiance, is something that many many people find offensive. I think many people felt offended by what the players did and that was fed into the unpopularity … and then of course POTUS Trump got involved, stirring things up quite a bit.

LATA: He was urging the NFL to fire these players. Many said that this was basically the POTUS telling people that they shouldn’t be exercising their right to free speech. Others said that by urging the NFL to fire the player the POTUS was exercising his own right to free speech. What do you think about this?

STEPHEN: In a way they’re both right. The President clearly has a right to freedom of speech – he can say what he wants and we certainly know he does that don’t we (laughing)? He speaks very frankly in his tweets about what he’s thinking, he doesn’t seem to filter much out. He exercises his right to freedom of expression. One of the things that made his comments so controversial is that, as the POTUS, despite the fact that he has this freedom, he’s in many ways undermining the right of the players to engage in protest and dissent in a place where they feel they can get a lot of attention. He’s done that trying to undermine expression and the press in many different ways and… you know, the press and expression are part of the fundamental values that we have in a democracy and, you know, people want to protest against him or against any government policy or against the NFL or against the police, they have the right to do so.

President Trump can express his disapproval of that exercise but… he’s doing it in a way that kind of riles people up and he’s asked for the punishment of players, he’s asked for the removal of – in some cases – tax benefits for NFL owners who don’t act against the players. A lot of people think that goes beyond the bounds of what the President should be doing.

LATA: Right. When you’re talking removing tax benefits you’re talking about the government taking action to impede free speech. Right? As opposed to just the POTUS voicing his view.

STEPHEN: Exactly. When the government passes a law or otherwise urges private parties to punish people for expressing their views then that’s the kind of suppression of speech that brings – typically brings – the first amendment to the forefront and causes a lot of controversy. It sometimes finds its way to the courts.

LATA: I talk about that a lot on this podcast. The first Amendment protects us from the government but not from private parties or private companies.

STEPHEN: That’s right. With the NFL players, they’re working for private companies. The first amendment to government action; private enterprises are not subject to it. The NFL clubs could potentially punish their players subject to employment laws (federal and state) and the agreement that the players have with the NFL. Those are potential limiting factors. Typically, the first amendment doesn’t come into play where a private employer disciplines their employees.

LATA: So, the NFL could punish these players? Legally?

STEPHEN: They could fire the players – they could discipline the players. Again, subject to the NFL Players Contract. It would be subject to any Federal discriminatory laws involving employees. It would be subject to state employment laws. The first amendment would have very little to say about that unless, somehow, the government was found to have put pressure on the NFL to discipline their players or the government tried to withdraw benefits from the leagues… something like that might, in some way, be the kind of government action that would activate the first amendment.

LATA: that brings me to my next question. Inspired by Kaepernick’s example, a lot of high school students and college students are also taking the knee during the anthem or sitting out the pledge of allegiance. Public high schools are considered to be government entities… does this change how a high school student at a public high school can be disciplined or punished for taking a knee? Do they have the same rights?

STEPHEN: If it’s a public high school we do have the first amendment applying and there have been some high schools that have disciplined their athletes for taking a knee during this past fall. This brings in the first amendment because public high schools are, basically, instrumentalities of the state. You go all the way back as early as 1943, the Supreme Court decided, in a very important case, West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnett, that high school students had the right, under the first amendment, to refrain from saluting the flag and engaging in the pledge of allegiance. The state could not force them to do so.

This is exactly applicable to the situation on, say, a football field at a public high school where players, imitating the NFL players, might take a knee or in some other way express their disapproval of the flag or their disapproval of the pledge of allegiance… they would be protected by the first amendment.

At a private high school you’re back to this situation where the first amendment would not apply. Of course, again, subject to any state laws that might say something to the contrary, they would have (the schools) to discipline their athletes if they felt that was necessary.

LATA: In terms of what a public high school could do would, say, saying that “the student can no longer play football” – could that be passed off as school policy?

STEPHEN: I think there’s probably some boundaries about the proportionality of the punishment versus what actually happens. I meant I don’t know they could kick someone out of school permanently, or for a long period of time, because they took a knee, even though the school would have, technically, the right to do that at a private school.

LATA: It’s been really interesting talking about the NFL protests and the various student athletes who have been inspired to protest based on that but I was wondering if we could talk about these protests in the context of protests in American history and how, say, the founders of our country use symbolic speech. Can you tell me a little bit about that? Your books “Revolutionary Descent” really goes into how the founders of this country developed Freedom of Speech, including symbolic speech.

STEPHEN: Symbolic speech was a central part of the protest movement against the British. When you get into the 1760’s and Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which was very controversial in the colonies and really in 1765, the 10 year road toward the Declaration of Independence and the outbreak of violence in the colonies against the Britain… So when Parliament passed the Stamp Act, immediately, in the colonies, a number of writers published articles and pamphlets with very long and involved arguments attacking the Stamp Act.

These were well-educated lawyers and politicians, sometimes they wrote under their own names like James Odis Jr. or John Dickenson; sometimes under pseudonyms, but what was common to these pamphlets was the learned nature of their expositions against the Stamp Act. They reached back in English history and law to argue against the Stamp Act. You have to keep in mind that a large proportion of the people in the colonies were uneducated, they maybe couldn’t read and even many who could were not educated enough to follow these arguments.

These lawyers and politicians were essentially writing for each other. In order to have any chance of convincing parliament to rescind the Stamp Act, the leaders, the Patriots, groups like the Loyal Nine in Boston (later, the Sons of Liberty) they understood that they had to popularize protest. They had to democratize descent. They achieved this with a stroke of genius.

In Boston, where most of this started, they enlisted the help of a fella’ named Ebenezer McIntosh who was a shoemaker and the leader of a large of group of blue-collar workers; artisans, ship-workers, things like that. He was their leader. Ebenezer McIntosh and his group put up effigies of the British Prime Minister and the local stamp distributor along with an effigy of the Devil. This happened on August 14th 1765 and as people came into the city of Boston on Market Day, they would see this huge elm tree from which were hanging the effigies.

Over the course of the day thousands of people came out, people who would have never read a pamphlet or an essay, you know, over the course of months this tree, which was later dedicated as a Liberty Tree, became a public forum for all kinds of meetings and mock trials of the Stamp Act and speeches and so forth… and more effigies paraded around town. All these things involved symbolic speech: the effigies, the Liberty Trees, the parades, the demonstrations, dressing up in all kinds of uniforms to mock the British, and it popularized descent… it brought people out… and not only the men but also women and children… people who did not normally participate in the political process.

This showed the kind of depth of opposition to this Stamp Act that quickly persuaded Parliament that they needed to do something… the colonies were not going to pay this tax, they were going to boycott, they were opposed to it strongly and so they rescinded the tax!

LATA: Did this spread throughout the colony? This use of symbolic speech and burning effigies?

STEPHEN: Yes! In fact, you can read the newspaper accounts in papers like the Boston Gazette. The papers were carried by horseback and by ship from city to city down the coast and the articles were reprinted and they stimulated the creation of more Liberty Trees and they began to appear all over the colonies. People would go out and they did exactly the same thing that the people of Boston did; hanging effigies in opposition to the tax, and this was not just, as it turns out, a protest against the Stamp Act because once that was voted out Parliament continued to pass laws that people in the colonies felt were very oppressive. They kept their Liberty Trees, their Liberty Poles, they continued to engage in all kinds of symbolic expression, you know, hanging people in effigy and so on. This became very much a part of the birth of freedom of expression.

I mentioned earlier that the clarity of the message was very strong, as I said, there were a lot of essays and articles written which came at these taxes and laws from various perspectives but when you were hanging the British Prime Minister in effigy, it was understood by everyone that what they were protesting was the oppression of the British.

LATA: And hey, you throw the Devil in there and I think the message is pretty clear.

STEPHEN: Well especially the Devil! You talk about the shocking nature of descent in some context and you think about symbolic speech and hanging the British Prime Minister and the Stamp Distributor along with the Devil… in Boston, with its Puritan theology, that was about as shocking and scandalous as you could possibly get. People would come out and they’d see the Devil! The incarnation of all evil in Puritan theology, hanging right there next to the British Prime Minister. That was very offensive to a lot of people.

LATA: Were people offended in the sense that they might have said “You’ve gone too far with this” – like Kathy Griffin’s fake severed head? Did people find it outrageous and obscene? Did it turn people off?

STEPHEN: Well it certainly turned some people off. The newspaper accounts are, some of them are, very celebratory about these protests and praising them but, you know, there was a loyalist movement of people who felt very strong connection to the King and many of them were certainly offended by it. There were writings by the British Royal Governor and other rural officials in America about how powerful these protests were and the fact that they… they kind of lost control of the city. The city was in the hands of those who were protesting and they couldn’t do much about it. Prosecutions for Seditious Libel trials couldn’t even be held! The citizens wouldn’t stand for it, and the British Royal Governors and Prosecutors could not get convictions or indictments because protests had become so popular that no one would condemn those on trial.

LATA: Fascinating! Symbolic speech is very powerful stuff. I didn’t know.

STEPHEN: Well yeah, that’s what spread protest through the colonies; this very vibrant form of expression that brought people out, that had immediate impact and meaning, and gave the opportunity for people to engage in political theater. The hanging of effigies, the marches around town, the dressing in costumes, all these things were political theatre that, itself, drew attention. People had fun at these events. They didn’t have Twitter or Facebook but they certainly made the most out of what they did have. One can only imagine if these very inventive people from the 1760s and 1770s were alive today, what they would make of our forms of communication because they were so inventive and creative with the limited things that they had available to them.

LATA: That’s an interesting point too, that this gave people the chance to have fun with it. It seems like the symbolic speech kind of democratized the whole process because before that you had scholarly articles that a lot of the population wouldn’t or couldn’t read.

STEPHEN: Yeah. And another example of the political theatre of it all was the number 45. We were talking about effigies and liberty poles but the number 45, as a number, became a symbol of protest. 45 referrers back to John Wilkes in England who is a member of Parliament and who published a newspaper in Britain. In the 45th issue he criticized King George to King George III and was prosecuted for Seditious Libel and he became a martyr to liberty and the number 45, the number of the issue, became a symbol itself.

There was a protester in New York, named Alexander McDougal, who was jailed, awaiting trial for Seditious Libel, for protesting against a law passed by the New York Assembly under the Royal Governor, and instead of paying bale, which as a merchant he could have easily done, he stayed in jail and he became a martyr to liberty in America. All over New York, and throughout the colonies, the number 45 was associated with him and so 45 people would visit him in jail and they would hold with 45 toasts drinking 45 glasses of wine among them and then they would… you know, everything was 45.

LATA: I wish I had a number associated with me. That’s very cool.

STEPHEN: So, this became, you know, Alexander McDougal and John Wilkes and the number 45, became emblematic of liberty and of protests. Again, using numbers, in this case, creating political theatre around it drew attention to the protest and the repression of speech and it rallied people to the cause… that was the whole purpose of it. He could of left, but he stayed. Over the cold winter of 1870 he stayed in a jail, enjoying the number 45.

LATA: That’s fascinating. That kind of tells me that anything can be a symbol so long as it’s something people can understand and rally around.

Thank you so much for putting the protests of today into historical context. It’s nice to have a reminder that we are a nation built on political theatre.

STEPHEN: It absolutely started hundreds of years ago, and it goes on today taking knees at football games and I’m sure it will go on from here. Thanks so much for having me.

LATA: I only wish this was our 45th episode! Thanks so much for giving us your time.

Tags