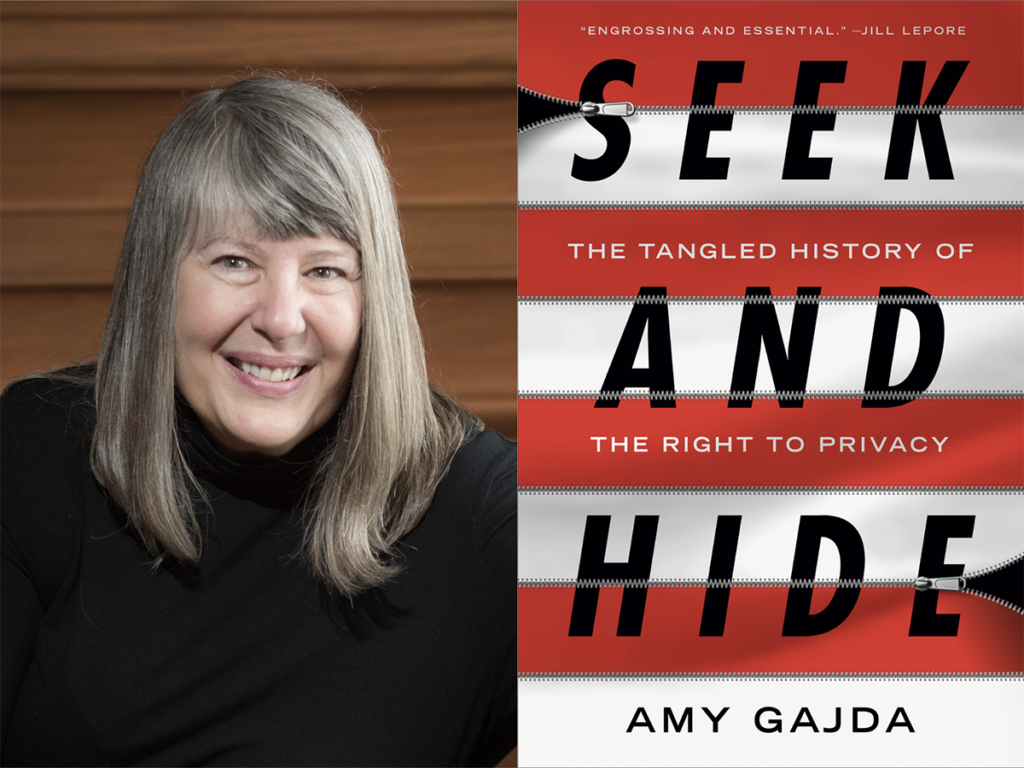

In “Seek and Hide: The Tangled History of the Right to Privacy,” one of The New York Times’ top 100 notable books of 2022, Amy Gajda “links our present struggle to an underappreciated tradition in American law and thought. She argues that although the right to privacy may have been a 19th-century innovation, privacy sensibilities have since the nation’s beginnings served as a durable counterweight to the hallowed principles of free speech, free expression, and the right to know. Ranging across several centuries, her account of the determined fight to protect privacy sounds like just the sort of road map we could use right now.” – The Atlantic

Amy Gajda is the Class of 1937 Professor of Law at Tulane University Law School and a former journalist whose work navigates the tensions between privacy rights and protected expression. Her work examining First Amendment limits on judicial oversight of the press and academia appears in leading law reviews and she has presented her work in Australia, China, England, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, and throughout the United States. Two of her books — “The First Amendment Bubble: How Privacy and Paparazzi Threaten a Free Press” and “The Trials of Academe: The New Era of Campus Litigation” — were published by Harvard University Press.

Amy Gajda — “Seek and Hide: The Tangled History of the Right to Privacy”

Amy Gajda — “Seek and Hide: The Tangled History of the Right to Privacy”

From “SEEK AND HIDE” by Amy Gajda, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Amy Gajda. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Adaptation of Chapter One, “Brandeis’s Secret,” pages 3-12.

It was 1884 and Louis Brandeis was just another budding Boston lawyer getting ready for oral argument before the members of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. The justices were all men, all lined up at a bench behind a do-not-approach railing, with marble busts of the learned looking down from niches above. Brandeis’s friend Oliver Wendell Holmes had joined the Massachusetts high court just the year before.

Brandeis was about to argue his very first right-to-privacy case. It’s one that in later years he didn’t like to talk about, and in any event it’s been overshadowed in history by things that occurred six years later. Brandeis would lose the battle that day, but that was not at all surprising; he was representing a publisher at a time of grave concerns about privacy, after all.

In the mid-1880s, at the height of the Gilded Age, the exterior of polite society gleamed, but things festered underneath. Sensational newspapers had exploded onto the scene, eager to expose the nation’s underbelly, book publishers were trying to keep up with readers’ growing taste for scandal, and the rich and powerful complained bitterly that these newfangled publishers had become far too interested in private matters.

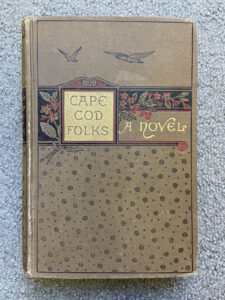

Had there been a poll that day in 1884, in fact, most everyone in the United States would have said that they were against Louis Brandeis. His client, A. Williams & Company, had published a book titled Cape Cod Folks that reveled in the humiliating secrets of Cedarville, a cloistered hamlet on Cape Cod. It was written by a young woman, boarding-school bred, who’d slummed it as a schoolteacher for a couple of seasons. She’d lived among the townsfolk, had become their friend and confidante, and had secretly taken fastidious notes in preparation for an exposé of their small-town lives. The author of Cape Cod Folks was initially anonymous, but everyone in Cedarville knew straightaway that it was Sally Pratt McLean.

Cape Cod Folks became a bestseller; reviewers, who thought it a novel, gushed over what they called the remarkably realistic prose. The author had a “keen eye for the ridiculous,” they said, and the “quaint and homely” queer characters offered genuine amusement as they went about their lives in “a poor little apology for a village,” “one of the most desolate and forlorn places on the cape.” McLean “d[id] not spare their poverty, their ignorance, their awkwardness, their pettiness; all these [were] told with a sharp pen, with genuine disgust, or with hearty laughter.”

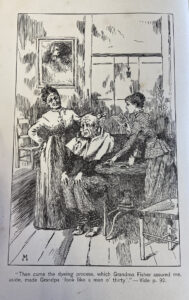

One key story line featured a decrepit character named Grandpa Fisher, hopelessly confused, weak, and defenseless, dyeing his scraggly gray hair black so that he might look like a man of thirty, only to end up, in the author’s assessment, neither old nor young, human nor inhuman. There was an etching at the front part of the book that showed as much.

Then there was Zetta, one of the older students. She confessed that she’d been wooed by a sailor into doing the “worst.” “Oh, I wish I was dead!” she told her teacher. “It’s the sin and the shame.”

And who wouldn’t be captivated by Lorenzo Nightingale, Grandpa Fisher’s neighbor, an unsophisticated youth just a smidge from manhood who’d made a heartfelt boyish pass at the teacher? “I should like to kiss you just once tonight and mean it,” he told her, and then did it more than once. If he set off to work real tight, and maybe came back lucky in a few years, might he have the teacher’s hand in marriage? Or would she continue to trifle with him even then, simply because he was raised poor and ignorant?

It took awhile, but readers outside Cedarville soon caught on that those quaint and homely, queer and amusing, awkward and poor characters appeared both on the pages of Cape Cod Folks and on one single page in the U.S. census. As one critic put it, the trouble with the book was that it was “too true.” In response to growing alarm about the truth of it all, the publisher promised to change the real-life names in future editions. It also sent out a sorry-not-sorry apology saying that it “deeply regret[ed] that the feelings of anyone should be injured by the innocent fun contained in the book.”

Adelaide Fisher, the thirty-one-year-old daughter-in-law of Grandpa Fisher, was one of those injured. She’d brought Sally Pratt McLean to town and had given her room and board; Adelaide’s husband was away at sea, she had her hands full with two little kids, and she longed for some adult company.

For a while, Adelaide didn’t trust Sally. But then she did.

Adelaide was particularly devastated by her portrayal in the book: McLean had described her as a frail little woman, not pretty, with a tired, tense look about the mouth and a way about her that made her seem sorely discontent. It was easy for Adelaide to get out of temper, and she often slapped the children. She missed her husband terribly, and she worried about his fidelity, especially when letters from the sea stopped coming. Adelaide had turned to religion for comfort, and when she led the town prayer meetings in song, her voice was strangely sweet and rapturous in its pathos and pathetic quaver. “Shall we meet beyond the river,” she sang, where “sorrow ne’er shall press the soul?”

Precisely eleven months to the day of the book’s announcement in Publishers’ Weekly came word that Adelaide had died. The official cause of death was consumption, but everybody knew what had killed Adelaide Fisher: “the unpleasant notoriety forced upon her by that book,” as her doctor put it, the embarrassment of it all. She’d left behind her mariner husband, an eight-year-old daughter, and a seven-year-old son.

Before she died, Adelaide had joined in a lawsuit for libel and ridicule against the publishers of Cape Cod Folks. Grandpa Fisher had joined it too, and together with three other plaintiffs they argued that the book had crushed their dignity; they’d taken Sally Pratt McLean into their homes out of kindness and friendship, and she’d proved to be a “viper.” Eventually, four of the five plaintiffs agreed to cash settlements with Brandeis’s client, A. Williams & Company, and thereafter dropped out of the lawsuit.

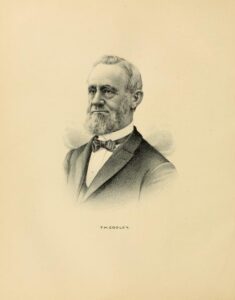

The sole holdout was Lorenzo Nightingale, the teacher’s would-be suitor. He took his case to a jury, the publisher argued in response that it had every right to publish the truth about his mostly unrequited love, and jurors awarded Lorenzo $1,095, quite a lot in 1884, about $30,000 today.

The day after the verdict, the Boston Daily Advertiser criticized Cape Cod Folks as “an attack . . . on the proprieties of private life.” Many in this age of increased reading and writing, the Advertiser suggested, believed that no verdict could be too excessive for simple country folk who deserved life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness and had instead been humiliated by those who would steal into intimate moments and reveal them. The Nightingale case pressed the question of how far publishers may legally violate the decencies and proprieties recognized in the ordinary relations of life. It wouldn’t be long and shouldn’t be long, critics said, before readers would demand the same sort of restraint from the greatest offenders, the day’s newspapers that seemed increasingly hell-bent on reporting the same sort of embarrassment and scandal.

Louis Brandeis, whose reputation was on the rise throughout the Northeast, was brought in by the publisher on the Nightingale appeal. He found himself in a bit of a hole there, given all the pushback in the court of public opinion. A clever lawyer needed both to protect his client and to recognize in some way Nightingale’s profound embarrassment at the revelation of otherwise private passions.

The World newspaper. Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana

The trouble was—and Brandeis surely knew this—that his friend Oliver Wendell Holmes, despite being the son of a famous poet, was no fan of the day’s increasingly unrestrained publishing. Holmes had become a judge the same year that Joseph Pulitzer had purchased The World in New York City, promising a change in methods, purposes, and principle in the newspaper, and a Pulitzer sort of sensationalism was already creeping into the Boston papers. A defiant Holmes, in a very early case that questioned a newspaper’s right to publish truth, had therefore held The Boston Herald liable for publishing a 100 percent accurate story about a certain attorney who was facing disbarment. To give the public knowledge of such a personal thing, Holmes had written in Cowley v. Pulsifer, was inappropriate, because it threw no light upon the “administration of justice.”

Oliver Wendell Holmes. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing

You might think that all newspapers would have rallied against the Holmes decision as some sort of unconstitutional restriction on their news judgment, but they didn’t. There were indeed rumblings of such a defense mostly in state courts back then, and some judges had written things like “a free press [is] one of the strongest bulwarks of liberty, and the people of this country have ever guarded it with jealous care,” but it would take decades before the First Amendment itself would prove so protective in an official sense. Besides, some newspapers at the time proudly distinguished themselves from their more scandalous cousins; the Boston Daily Advertiser, for example, headlined its story about the Cowley decision “A LEGAL LIMIT TO “ENTERPRISE’” and found that limit perfectly agreeable. In light of Cowley, the Daily Advertiser’s editorial read, “It [would] not be unreasonable to hope that before long the honest citizen m[ight] find some way to make his privacy respected.”

Holmes kept that newspaper clipping in his papers until he died. He’d also asked that the permanent privacy of his personal letters be secured by burning or some other destructive method. “I don’t know whether you feel so,” he wrote to a friend named Harold Laski many years later, “but I like to think that no more of me will be made public than what I have made so.”

But that’s a privacy story for the twentieth century.

_________

The Holmes bench book for 1884–85, his personal record of court cases and their outcomes, suggests that Holmes himself was to write the opinion in the Cape Cod Folks case but then, for some unknown reason, Justice Walbridge Field agreed to take over. This was surely an additionally ominous sign for Louis Brandeis. That’s because, like Justice Holmes, Justice Field had sided with the plaintiff and against a newspaper in a case involving a truthful article. There, journalists had accurately reported that a local minister had been forced out of his church for brutalizing his daughters through “horsewhippings for trivial offences, systematic starving, feeding of rotten meat, and positive dishonesty and faithlessness in his family relations.” Editors testified that they’d shared the news in the interest of society and the public good.

Justice Field wasn’t at all impressed with that judgment call: the truth of the words published is not an absolute defense, he wrote, because what counted was whether the newspaper had acted with a malicious intent in revealing the truth, the heart of the plaintiff’s claim. The public’s right to know, after all, had its limits, and because the jury had found such limits perfectly satisfactory in this particular case, its verdict would stand: the newspaper owed the horsewhipping, philandering minister $1,000. Case closed.

By the time Brandeis stood in front of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in 1884, in fact, more than 250 court opinions from across the United States had mentioned the word “privacy” in some way. Courts had focused on the privacy of the home (the “right of quiet occupancy and privacy was absolute and exclusive”), and on the “privacy of domestic life” or, even better, the “sacred privacy of domestic life.” Others had noted the privacy inherent in sexual relations (“illicit intercourse of parties is generally consummated in the strictest privacy and secrecy, and is known only to the parties themselves”) and the privacy in telegrams (the “destruction of the happiness of whole households” would otherwise be “brought to light and hawked through the country by scandal-mongers”). It all suggested the need for strong privacy protections especially within the family: “Of what occurs in the privacy of the family circle,” outsiders “can know but little or nothing” because “lifting the veil from the domestic sanctuary [would] expose to public view the secrets and scandals of private life,” a violation of the common law (or court-decided law). A California judge had written quite specifically that the conversation of intimate friends may not be shared either and that any invasion of domestic circles would encourage an evil “system of espionage abhorrent to American ideas.” Sure, that case involved a police informant who’d spilled the beans, but the language was powerfully protective more generally.

Meanwhile, in Michigan, Justice Thomas Cooley of that state’s supreme court had come up with a catchy phrase in his influential treatise on tort law that neatly described such privacy sensibilities: the right to be let alone. He’d also joined in an opinion several years earlier that said flat out that the general public “has no concern whatever with the lawful doings and affairs of private persons.” Cooley’s “right to be let alone,” in fact, had caught on much more quickly than a related phrase on the other side of the coin minted that same decade: the “right to know” the truth of things.

This body of law and opinion seemed to give the Cape Cod Folks plaintiffs a sound legal path to victory and the defendant an impending defeat at the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, but nothing was spot-on precedential, so Brandeis argued in a sort of Hail Mary pass that his client’s behavior was wrong but not actionable. Yes, there’d been emotional harm done to Lorenzo Nightingale, the young man who’d bared his heart to a teacher who’d then told the rest of the world about it, Brandeis argued. But that sort of wrong wasn’t yet on the law books—libel meant harm to reputation, he argued, and ridicule “laughs down,” not with or up—and this was therefore only a breach of the canons of propriety and good manners. The civil law didn’t address eavesdropping or looking into one’s windows either, Brandeis noted, so it certainly didn’t recognize this publication-related “invasion of the plaintiff’s domestic privacy.”

As proof of the law’s failure to support privacy, Brandeis mostly cited cases from England that really weren’t all that helpful to him; this brief didn’t sing like those that he’d later become famous for, those that incorporated compelling facts, public policy matters, and nonlegal argument. He surely must have been thinking that Lorenzo Nightingale was a much more sympathetic plaintiff than a brutalizing excommunicated minister or an attorney facing disbarment.

Even the facts weren’t on Brandeis’s side in a case that he himself had called a privacy invasion.

_________

Oral argument at the time was usually followed by a published decision within a few weeks. So when the rest of October, November, December, January, February, and March all passed with no word from the court, Brandeis surely knew that he was in trouble. An opinion in the publisher’s favor would have been easy to write, because all that the justices would have needed to say was that the law didn’t recognize a privacy claim, just as Brandeis had argued in his brief and at oral argument. No legal support for something called a right of privacy? Short opinion quickly written.

But if the court had decided that folks like Nightingale had a right to privacy by name? That sort of intricate opinion that built upon layers of existing law would have taken a little longer. Importantly, such an opinion would have also stopped the Cape Cod Folks gravy train; Brandeis’s client had already published more than seventeen revised editions as the lawsuit dragged on, and revenue from those had to have been a consideration.

Meanwhile, on a more personal level, it probably didn’t help matters when Brandeis’s cousin, a famous medical doctor, suddenly went missing, and newspapers around the nation began to report intriguing details about the man and his immediate family. Had the prosperous Dr. Richard Brandeis suddenly gone insane? Was he wandering around demented, leaving his wife prostrated from grief and anxiety? Or did his disappearance involve something more sinister? Nobody, surely not even a publisher’s lawyer, could celebrate that sort of spotlight on family tragedy.

Louis Brandeis therefore did what any thinking defense lawyer would have done and he settled Lorenzo Nightingale’s claim. That meant the case ended right there, before any decision on the appeal by the court. Nobody knows for sure what the publishers paid Nightingale because nobody can find the case file at any Massachusetts courthouse; they say that back then, after settlement, everything was destroyed because the case could no longer be revived and there seemed no reason to keep anything. Only the handwritten trial court notation, Justice Holmes’s bench book marked “settled by parties before decision,” the court docket, old newspaper accounts, and Brandeis’s appellate brief bound with others as a memento for his daughters prove that it ever happened.

That means we don’t know for sure what legal precedent the plaintiffs used to support their claims for libel and ridicule against Brandeis’s client in the Cape Cod Folks case. But there’s a hint in news coverage of the case, and an interesting twist. The magazine The Literary World, surely helped along by the plaintiff’s lawyers, suggested that the patriot Alexander Hamilton, now dead some eighty years, would have seen it Lorenzo Nightingale’s way: Hamilton, the editorial read, had embraced and supported the ideal of a free press to some extent for sure, but had also condemned mischievous, painful writing that ridiculed others.

That is pretty much correct. And that story—one involving not only Hamilton, but Thomas Jefferson, other Founders, and the journalists who covered them—would come to have an even more significant impact on the law of privacy in the new United States.

Tags