Professor Collins is the Harold S. Shefelman Scholar at the University of Washington School of Law. He specializes in First Amendment law, constitutional law, and the law of contracts. Before coming to UW in 2010, he was a scholar at the First Amendment Center in Washington, D.C. He received his law degree from Loyola Law School in Los Angeles (law review) and his bachelor’s degree from the University of California at Santa Barbara (political philosophy). He clerked for Justice Hans A. Linde on the Oregon Supreme Court and was a Supreme Court Fellow under Chief Justice Warren Burger. After working with the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles and the Legal Aid Society of Orange County, Collins was a teaching fellow at Stanford Law School. Thereafter, he taught constitutional law and commercial law at several leading schools, including George Washington University Law Center and Temple Law School. He is the editor of The Fundamental Holmes: A Free Speech Chronicle and Reader (Cambridge University Press, 2010) and the co-author of We Must not be Afraid to be Free: Stories about Free Speech in America (Oxford University Press, 2011). His other co-authored works include The Death of Discourse (2d ed. 2005) and The Trials of Lenny Bruce (2002). He is also the editor of The Death of Contract (1995) and Constitutional Government in America (1980). His numerous articles have appeared in a variety of publications, including the Harvard, Stanford, and Michigan law reviews and the Supreme Court Review. Collins was selected as a Norman Mailer Fellow in fiction writing with a residence in Provincetown (Winter, 2010), this in connection with a forthcoming novel and collection of short stories. He is also the book editor for SCOTUSblog and the Journal of Legal Education, the editor-in-chief of FIRE’s online First Amendment Library, the founder and co-chair of the First Amendment Salons, and co-founder and co-executive director of the History Book Festival (Lewes, DE 2017).

Ronald K.L. Collins Responds to Louis Michael Seidman’s “Can Free Speech Be Progressive?”

Let us not speak falsely – A call to candor from one progressive to another

If one is to be true to the spirit of the First Amendment, one must be open to speaking frankly about it . . . and about the risks posed by it. After all, it is too late in the conceptual day to think of the First Amendment as a machine perpetually producing bounties of freedom lacking of any cultural costs. Mind you, this is not an argument for abridging such rights. Rather, it is a call to candor. That call was heeded recently by Professor Louis Seidman in a thoughtful essay he wrote: Can Free Speech Be Progressive? I commend Professor Seidman for it, if only because his words invite us all (progressives, liberals, libertarians, conservatives, et al) to rethink our thoughts about free speech in America. In that spirit, a collegial one, I raise nine questions for my fellow progressive.

I. What about the culture of the First Amendment?

There is more to the First Amendment than what law professors and lawyers trade in; that is, there is more than Supreme Court cases. There is the culture of the First Amendment. Perhaps (?) that is what you refer to in your reference to the “sociological . . . baggage that comes with the modern, American free speech right.” In many diverse ways, our culture protects a wide range of progressive values, among others, many well beyond the letter of Supreme Court decisional law. To cabin the First Amendment in case law is to overlook a hefty dollop of our modern freedom. Does your sociological reference include the culture of free speech, and if so, how, if at all, does that affect the logic of your argument?

II. Can a progressive have an open mind?

Are there limits to open-mindedness? Just how much latitude can a progressive mind tolerate? Might such open-mindedness, at least at some critical point, be seen as an anathema to progressive values? But if so, does that mean that the only free speech liberty progressives can tolerate is progressive liberty? Were that to be the case, then where does that leave us when it comes to the First Amendment? Wasn’t part of the compromise inherent in the 1791 guarantee the idea that opposing views and values would somehow be tolerated? (Remember: toleration has long been the mantra of progressives.)

Louis Brandeis 1915 portrait, a year before he joined the United States Supreme Court.

III. What is a progressive & when does one cease to be one?

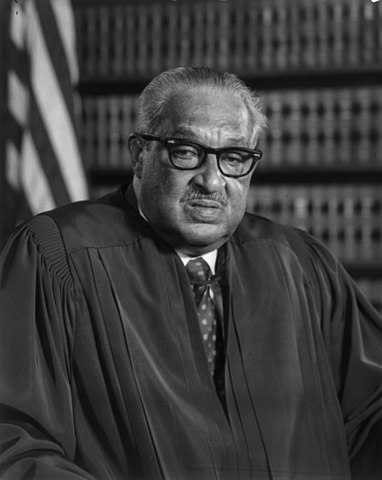

Let us not forget that Justice Louis Brandeis, that great progressive, once voted to sustain the First Amendment claim of an anti-Semitic bigot. On another occasion he denied the First Amendment claim of a woman who dared to speak her mind in support of the Communist Labor Party of America. Or what about Justice Thurgood Marshall’s vote to sustain a free speech claim raised by KKK cross burners? Then there is John Paul Stevens’ dissent in the Texas flag-burning case, the same one in which Justice Scalia joined in the judgment to sustain the First Amendment claim. And let us recall the key role Justice Brennan played in constitutionalizing protection for campaign expenditures. Do such rulings run afoul of progressive ideals, concerns relating to “unjust distributions” and dismantlement of “power hierarchies based on traits like race”? Were these examples of progressives (or their fellow travelers) refusing to toe the progressive party line?

IV. Is protecting commercial obscenity a progressive value?

I ask this because it seems that given your account of progressive values re discrimination, hierarchies, and dignity, arguments like those advanced by Critical Legal Studies scholars and feminist thinkers would have a view quite contrary to yours. No? Isn’t the commercial exploitation of women contrary to progressive values? If so, then do you side with anti-pornography feminists like Catharine MacKinnon? If not, do you agree with Anthony Lewis’ portrayal of such views as a form of “repression” from the left? What is your take on this?

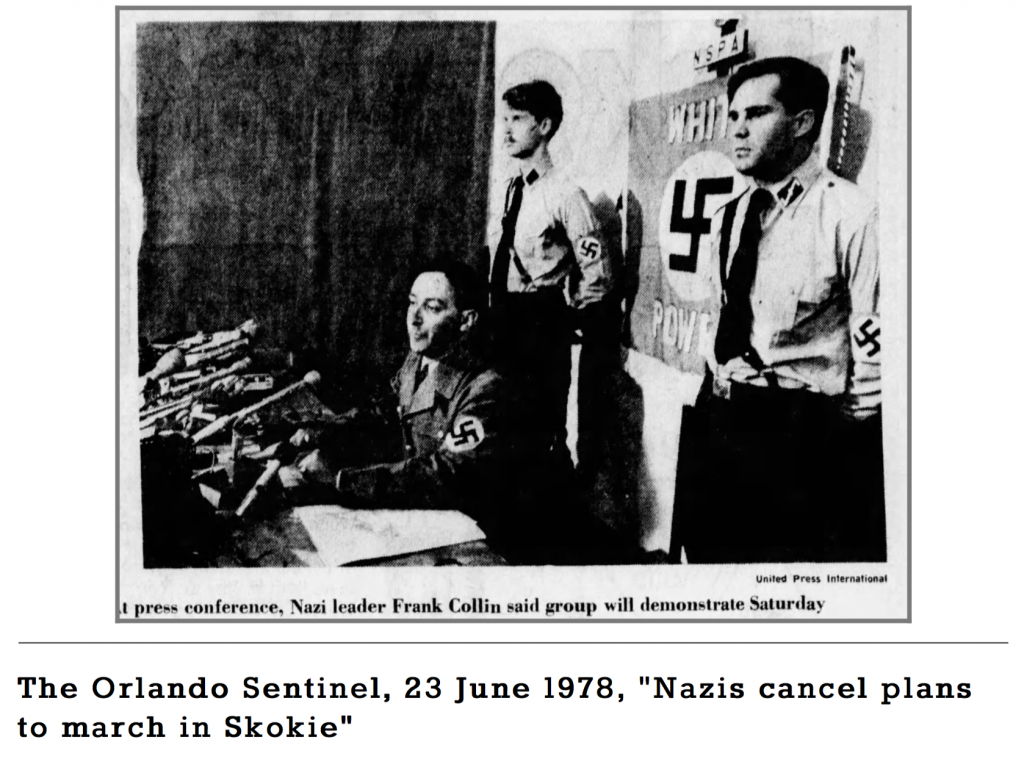

(Credit: Newspapers.com)

V. Are the words progressive and liberal synonymous?

In the text of your essay, the term liberal or liberalism is used a mere three times, whereas the term progressive is used numerous times. What are we to make of this? Is there a difference between the two? Are progressives to the left of liberals? If so, how and to what extent? Might a liberal retain her liberality in sustaining a First Amendment claim, in say a Nazi speech case, whereas for a progressive to do so would be a breach of her progressive ethic? Does that explain the ACLU divide in the Skokie case? If so, has part of the ACLU moved along the political spectrum from progressive to liberal . . . or even worse?

VI. Is the First Amendment the real progressive problem or is it the rights regime?

Might many of the arguments you level against First Amendment rights be leveled as well against our modern fixation with rights generally, especially in a highly advanced capitalist culture? For example, there are property rights, gun rights, rights of the unborn, criminal rights, and anti-discrimination rights (e.g. in the context of affirmative action), among others. Is not the real problem a larger one, of which free-speech rights are but one example? That problem, to borrow from the thought of Simone Weil, resides in very the notion of individual rights – the kind of selfish individual claims that blind us to those fundamental obligations owed to all humans. If so, is not the most glaring problem with rights generally, rather than any particular claim of right?

VII. What about the consequences of capitalism?

You write: “shielding the speech power from political redistribution. For a period it may have seemed that speech rights could be protected from the political branches while subjecting economic entitlements to political adjustment. But because speech opportunity depends upon property distributions, this compromise was always doomed to failure. The Court might have eviscerated the speech right by allowing the political branches to manipulate its economic substrate. In recent years, it has chosen instead to invigorate the right by imposing Lochner-like restrictions on the property entitlements that make speech possible. The results have been disastrous for progressives, but the disaster is a necessary consequence of taking free speech seriously.” In short form, I take it by “Lochner-like restrictions” you mean constitutionalizing of commercial values.

Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall

I italicized the words in your essay in order to ask two questions: (1) exactly what compromise?, and (2) taking free speech seriously in exactly what context?

I raise these questions to echo what David Skover and I wrote a quarter-century ago: “Communication is the handmaiden of commerce.” We tendered that claim as a realist observation rather a normative one. Make of it what you will, but none can deny that we live in highly commercialized capitalist culture. Commercial speech is a part of that culture. Given that, is not your real complaint against the capitalist culture in which commercial speech is (not surprisingly) rooted? More, much more, could be said on this score, but suffice it to say that gauged by this commercial measure, the key threat to your progressive regime is modern capitalism – the very kind that so many Americans revere. Well, what say you?

VIII. What about First Amendment lawyers?

There is a group known as The First Amendment Lawyers Association. Their members pride themselves on having protected “Free speech nationwide for over 40 years.” They protect any variety of free speech rights – and that’s the idea! Is this the kind of organization for which a progressive lawyer must leave her ideological credentials at the door? Would fidelity to her progressive faith limit her to the kind of free speech cases litigated by members of The National Lawyers Guild (whose motto is “human rights over property rights”)?

IX. What about conservatives?

When I read “Can Free Speech be Progressive?,” I thought: might a similar question be asked in the case of conservatives? In these modern times, it is easy to forget just how much free speech freedom was (and remains) antithetical to conservative values. If you doubt that, just read Hadley Arkes (circa 2018), George Anastaplo (circa 2007), David Lowenthal (circa 1997), Francis Canavan (circa 1984), or Walter Berns (circa 1957). What do you make of this?

Coda. More thoughts race through my mind, but let me pause here and see how the discourse plays out. Meanwhile, I wish to thank Professor Seidman for prompting the kind of sincere and straightforward talk so vital to any self-respecting constitutional democracy. Finally, if I have put too much on your plate (at least for now), then I am happy to take a rain check for answers to any you might save for another day.