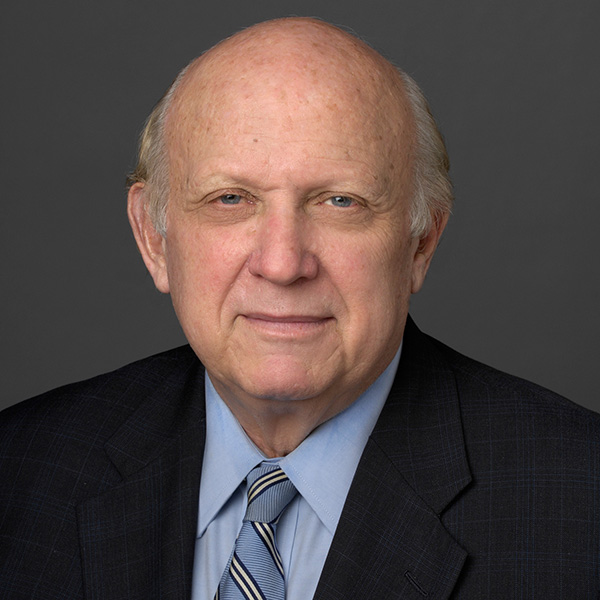

Floyd Abrams is senior counsel in the New York law firm of Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP and an adjunct professor at New York University School of Law. He has argued frequently in the Supreme Court in First Amendment cases ranging from the Pentagon Papers case to Citizens United. His clients have included the New York Times, ABC, NBC, CBS, CNN, The Nation, Reader’s Digest, Mediaite, the Brooklyn Museum, and many others. Abrams has taught at Yale Law School, Columbia Law School, and, for fifteen years, as the William J. Brennan, Jr., Visiting Professor of First Amendment Law at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism. At Yale Law School he has founded the Floyd Abrams Institute for Freedom of Expression, which promotes freedom of speech and of the press.

Floyd Abrams Responds to Louis Michael Seidman’s “Can Free Speech Be Progressive?”

One cannot comment fairly about Professor Seidman’s offering without understanding who his intended audience must have been. They seem to be progressive scholars, like himself, who abhor the current state of First Amendment law on the ground, as he puts it, that it has not been sufficiently “weaponized to advance progressive ends.” His mission, it seems, is to persuade them that any hopes they may have are utterly unrealistic that with only a few changes in membership of the Supreme Court, First Amendment law could come to serve as “a powerful sword that would actually promote progressive goals.” Or that “the speech right could be refashioned so as to actually mandate progressive outcomes.” Those outcomes, he states, are ones in which “an activist government … strives to achieve the public good, including the correction of unjust distributions produced by the market” and the “dismantling” of certain “power hierarchies.”

“He dismisses recent First Amendment victories in the Supreme Court as a ‘radical right turn in free speech law’ as if they had been written by Stephen Miller from his White House desk rather than by not-so-radical jurists such as John Roberts or Anthony Kennedy.”

Professor Seidman seems to regret his conclusions—his tone is rueful throughout– but he nonetheless is candid with those whose political and social views that he seems to share that they should not expect the sort of legal turnabout on free speech issues that they would find more politically and socially satisfying. The case he makes to them is strong and it would serve the progressive cause if its proponents better understood First Amendment law, if only to denounce it with more accuracy.

United States Supreme Court Building

But Professor Seidman does not offer any argument that might persuade any of us who admire the sweeping protections the First Amendment affords to free expression even to begin to reexamine our view that “weaponizing” the First Amendment to achieve progressive ends would be any more constitutional than reconstituting it to achieve conservative ones. Or that the First Amendment could properly be reframed or understood to mandate either progressive or conservative outcomes.

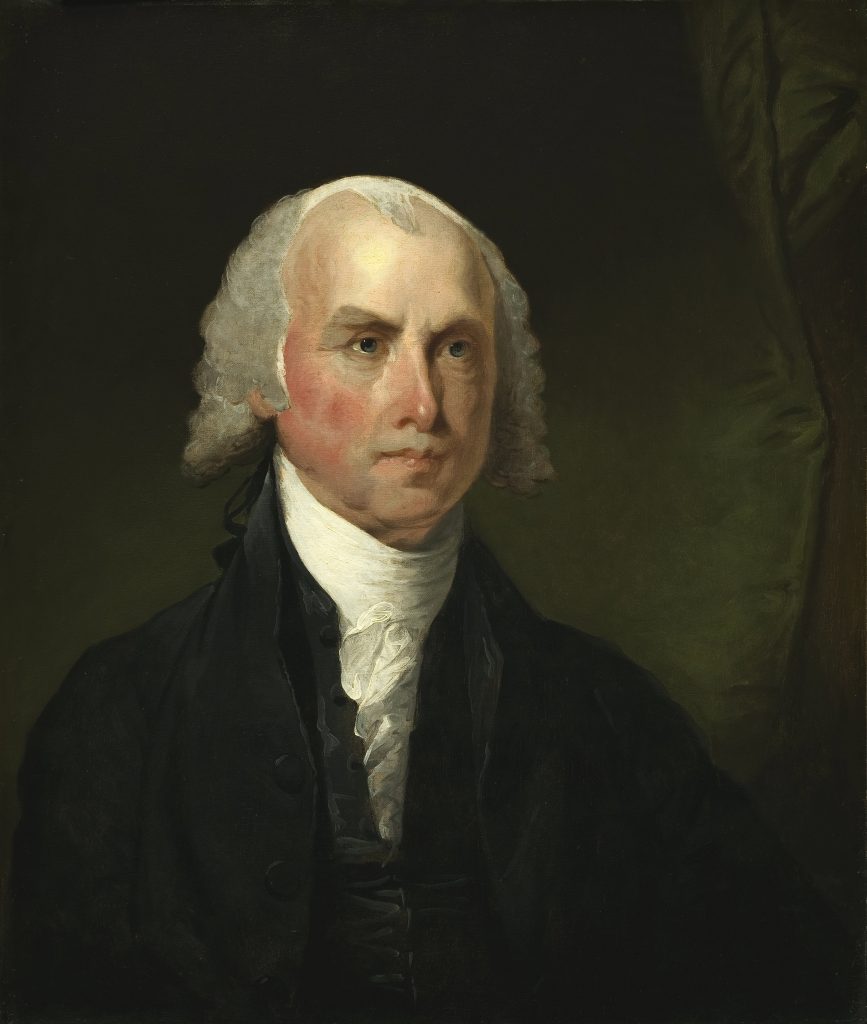

Professor Seidman offers too many assertions that only those who already share his views could possibly accept. He criticizes, with no accompanying exposition, current Supreme Court First Amendment rulings as being rooted in an “obsession with government restrictions on speech” as if a First Amendment that begins with the words “Congress shall make no law abridging” does not focus on government overreaching. Or as if Madison had not stated, in introducing the Bill of Rights in the House of Representatives, that their “great object” was “to limit and qualify the powers of government.”

James Madison

He dismisses recent First Amendment victories in the Supreme Court as a “radical right turn in free speech law” as if they had been written by Stephen Miller from his White House desk rather than by not-so-radical jurists such as John Roberts or Anthony Kennedy. He treats his own constituency—progressive lawyers, scholars and the like—as “victims” when their side loses cases in the Supreme Court rather than the people for whom they purport to speak or defend. How else can one understand Professor Seidman’s reference (without italics) to “proponents of campaign finance reform” as the supposed victims of the Citizens United case or “opponents of cigarette addiction” as having been victimized by a case such as Lorillard Tobacco C. v. Reilly? I happen to agree with both rulings but it never even occurred to me that those decisions somehow victimized those who disagreed with them.

Stephen Miller

All that being said, the essay is not only interesting but revealing. Most interestingly, Professor Seidman persuasively maintains that technological changes in the production and presentation of speech raise new issues about freedom of speech. He agrees with Professor Tim Wu that “speech clutter” rather than government suppression of speech is “the modern free speech problem.” He concludes from this that since speech aggregators are newly empowered by this state of affairs and since they “regularly shield consumers from ideas that are unfamiliar, upsetting, or inconsistent with a preconceived narrative “ it is progressive thought that tends to be filtered out.

Of course—and Professor Seidman presents this argument with absolute fairness—there is an alternative or at least additional reading of the new on-the-ground reality. It is nothing less than, as he summarizes it, that what is occurring is the “democratization of speech [which] breaks the link between wealth and speech opportunities.” His view to the contrary is not only serious but fascinating and the essay’s fair presentation of both views makes a substantive contribution to public discourse.

So is Professor Seidman’s conclusion, dubious but creative, that the very assertion of a constitutional right to freedom of speech is “dictatorial” in nature since the assertion of constitutional rights has the unintended consequence of avoiding debate about that which has been constitutionalized. Professor Seidman goes so far as to urge progressives to take care about invoking free speech claims, lest doing so winds up stifling debate rather than fomenting it. I doubt the validity of that hypothesis—the notion that protecting free speech by constitutional command really can wind up stifling it more than the absence of constitutional protection would—seems to me something only an academic would proffer. But that’s why practicing lawyers should keep reading academic offerings.

“Most interestingly, Professor Seidman persuasively maintains that technological changes in the production and presentation of speech raise new issues about freedom of speech.”