In his new book, “The Mind of the Censor and the Eye of the Beholder,” Robert Corn-Revere asks a simple question: what characterizes the psychology of a censor? For Corn-Revere, the attitudes of moral crusaders have been fairly consistent over the last 200 years: they are marked at once by a rigid certainty that the ideas they target are indisputably harmful and an insecure defensiveness stemming from the awareness that most people will reject their attempts at censorship. “[T]he plain fact is that the censor in a free society never has the moral high ground,” Corn-Revere writes, and the would-be-censor knows this. To separate himself from what he knows society will ultimately reject, the censor tries to convince everyone that his campaign is not censorship but something else. It’s a losing argument, but one that nevertheless reemerges again and again through U.S. history.

Neither party is immune from the “censorial impulse,” Corn-Revere writes, they only differ in their preferences. In this first chapter of “The Mind of the Censor,” excerpted here, Corn-Revere explains what unifies censors across time and partisan lines.

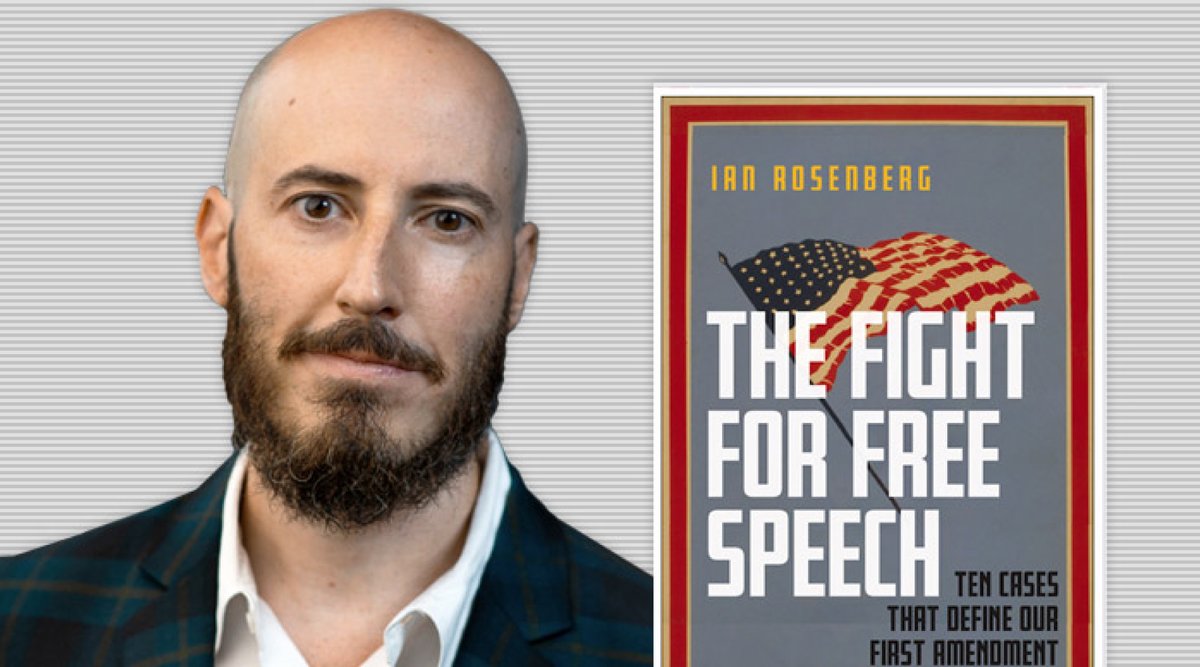

About the author

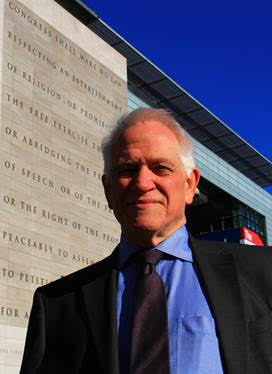

Robert Corn-Revere is a former Federal Communications Commission chief counsel and current partner at Davis Wright Tremaine. A leading First Amendment lawyer, Corn-Revere is well known for his work challenging government censorship of sexual speech and censorship on college campuses. For example, in 2000 Corn-Revere successfully argued the case of United States v. Playboy Entertainment Group (2000) before the Supreme Court, which involved a government policy banning television programs from airing sexually explicit content during the day.

Robert Corn Revere outside of the Newseum.

Corn-Revere has also represented college and university students in their fight against campus censorship. In 2015, he won in Barnes v. Zaccari, defending a university student and environmentalist who had been expelled for protesting the construction of a parking garage. And in 2017, he represented two student groups in Gerlich v. Leath who had their logo rejected because it contained an image of a Cannabis leaf.

More recently, Corn-Revere sued former President Donald Trump on behalf of PEN America for his threats and retaliatory acts against the press. Instead of focusing on a single policy or retaliatory act, the complaint argued that Trump’s repeated attempts to punish news organizations and journalists for critical coverage had created a chilling effect that discouraged writers from criticizing his administration. PEN America settled the case with the Biden administration after Trump lost the 2020 presidential election.

“The Mind of the Censor and the Eye of the Beholder” is available for purchase on November 4th, 2021. You can order your copy on Amazon and Barnes and Nobles.

This excerpt was republished with permission from Cambridge University Press 2021

The Censor’s Dilemma

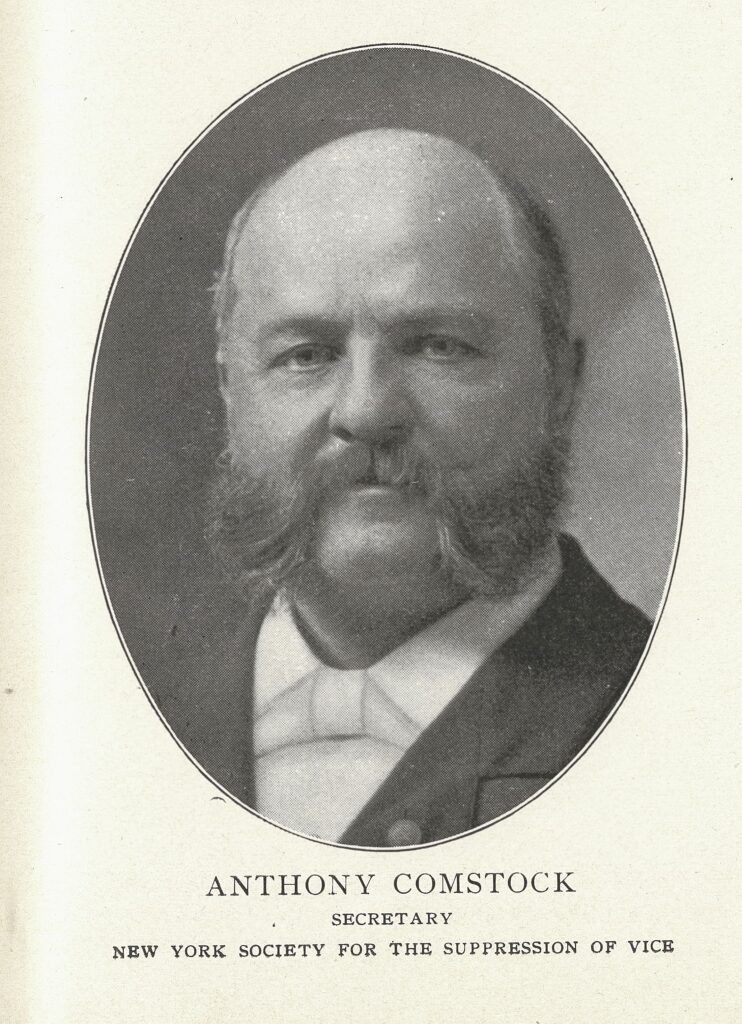

Pity the plight of poor Anthony Comstock. The man H.L. Mencken described as “the Copernicus of a quite new art and science,” who literally invented the profession of anti-obscenity crusader in the waning days of the nineteenth century, ultimately got, as legendary comic Rodney Dangerfield would say, “no respect, no respect at all.” As head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and special agent for the U.S. Post Office under a law that popularly bore his name, Comstock was, in Mencken’s words, the one “who first capitalized moral endeavor like baseball or the soap business, and made himself the first of its kept professors.”

Anthony Comstock, Secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, 1899. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

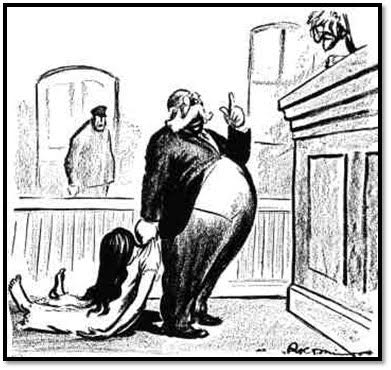

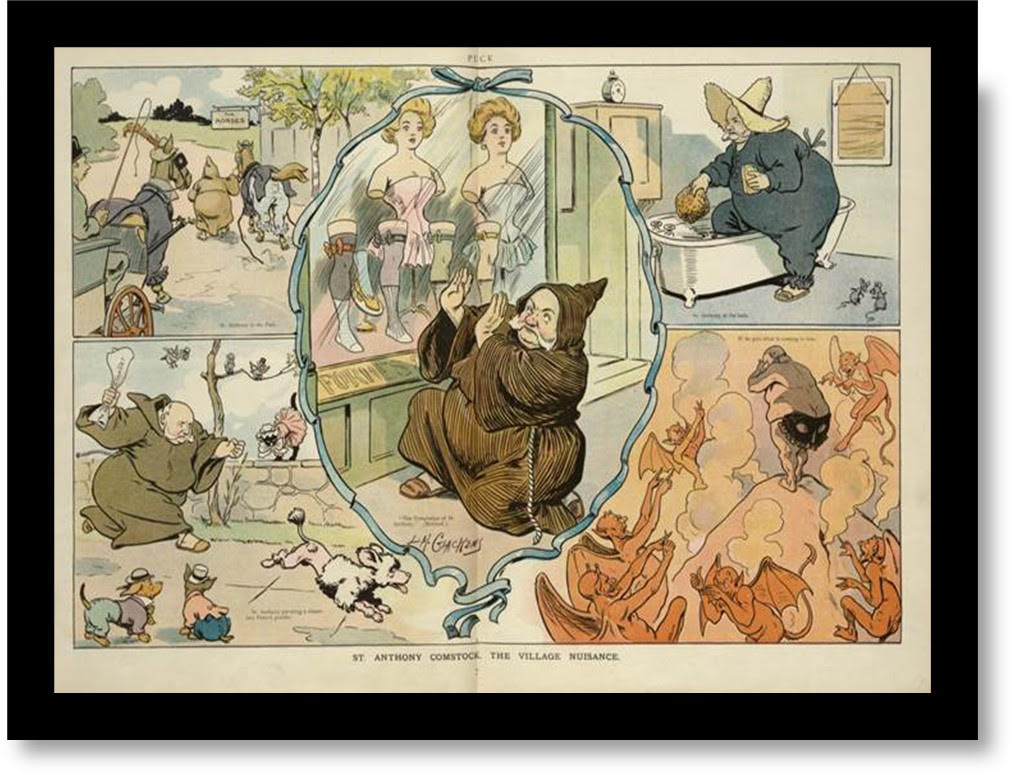

For more than four decades, Comstock terrorized writers, publishers, and artists – driving some to suicide – yet he also was the butt of public ridicule. George Bernard Shaw popularized the term “Comstockery” to mock the unique blend of militant sanctimony and fascination with the lurid that marks American prudishness. Comstock frequently was lampooned in illustrated comics, and in his final days, even his supporters distanced themselves from his excessive zeal. In this respect, Comstock personified the censor’s dilemma in a free society – the capacity to wield great power combined with the inability to shake off the taint of illegitimacy.

Comstock’s mindset lives on, both in the extension of his law to modern communications technologies, and in the army of Lilliputian Comstocks pursuing the same profession, but who, like Elvis impersonators, can never quite come close to the real thing. His outsized shadow looms over the likes of Dr. Fredric Wertham, the psychiatrist who stoked a national panic about comic books (Chapter 5), and Tipper Gore of the Parents Music Resource Center who leveraged her political connections to cow the music industry (Chapter 6). It dwarfs the impact of Newton Minow, JFK’s Federal Communications Commission Chairman, who endeavored to tell Americans that the television medium they so love is nothing but a “vast wasteland,” and who used the power of the FCC to homogenize broadcasting (Chapter 7). Comstock’s accomplishments also overshadow such lesser zealots as Brent Bozell, founding President of the Parents’ Television Council (PTC), an organization created to keep the world safe from fleeting expletives and wardrobe malfunctions. (Chapter 8).

This book examines the work of these and other would-be censors and explores reasons why, while destructive to freedom in their time, they had no permanent impact in the United States. Or, more accurately, they didn’t achieve their intended impact. This is not a partisan argument. No political philosophy has a monopoly on sanctimony, or on the belief that revealed truth – as its adherents define it – should be enforced as a matter of public policy. Progressives and conservatives are united in the common conviction that they know what speech should be banned (or required) and that their choices should be enforced by law; they only differ in their preferences. In this respect, the eye of the beholder governs the mind of the censor. But, in part because the arbiters of propriety wish to suppress or supplant what the public embraces, they are the ultimate counterculture warriors, and therefore, doomed, in the end, to failure and disrepute.

A fundamental(ist) disconnect

A more fundamental reason for the censor’s harsh fate is that his very existence contradicts the arc of history among societies that value freedom. From the time Anthony Comstock shuffled off into the void in 1915 to the present day, constitutional protections for the freedom of imagination and expression have become well-established to a degree Comstock could never have anticipated, and that would have horrified him. The year Comstock died, the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment’s protections do not extend to the then-new medium of cinema. It reasoned “the exhibition of moving pictures is a business, pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit,” and, more to the point, “capable of evil, having power for it, the greater because of their attractiveness and manner of exhibition.”

The Court’s opinion produced a result and employed a rhetorical style worthy of the great morals crusader himself, but would not stand the test of time. As both the sophistication and artistry of film evolved, the public enthusiastically embraced it, as did – eventually – the courts. When Comstock passed, the Supreme Court had not yet issued a single decision upholding any First Amendment claim. But over the next fifty years, the Court would decide that the medium of film was constitutionally protected in the same way as newspapers and books; that the government’s ability to impose prior restraints – to censor expression in advance of publication – was strictly limited; that sex and obscenity are not synonymous, and that discussions of intimate subjects could be banned only if they were “prurient” and utterly lacked redeeming social value. At the same time, both public and judicial estimations of what is socially valuable shifted radically. Since then, the legal component of the so-called “culture war” has continued to be waged along the border, and it is an ever-expanding frontier.

It is tempting to think of Comstock’s Victorian Era reign of censorship as a limited episode in our history – like the Red Scare and McCarthyism – that erupted for a time only to be left behind as law and social understandings evolved. But the reality is not so simple, if only because no such phenomenon is ever a one-time thing when we fail to learn from history. Even at the height of his power, Comstock was ridiculed almost as much as he was feared, and his death did not signal the end of the profession of moral crusader. Far from it. The names and faces may change, as do the specific problems that represent the latest threat to civil society (and usually to our children), but there has never been a shortage of volunteers eager to save us from our own bad taste and poor manners.

“[T]he plain fact is that the censor in a free society never has the moral high ground.”

One defining moment for what we have come to know as the “culture war” at the start of twenty first century, was the Janet Jackson/Justin Timberlake “wardrobe malfunction” that ended the halftime show of Super Bowl XXVIII in 2004. Although the broadcast network immediately apologized for what turned out to be a poorly-planned and flawed execution of a last-minute stunt secretly contrived by Jackson and her choreographer, policy entrepreneurs like Brent Bozell immediately pounced on the 9/16-second flash of bejeweled breast flesh as a sign of the End of Days and a call to arms. The FCC instantly launched a major investigation; Congress convened a series of hearings; and Michael Powell, the FCC’s Chairman at the time, initiated a number of steps designed, as he put it, to “sharpen our enforcement blade.” The Commission ultimately fined CBS over half a million dollars for the unplanned and unauthorized moment which the agency nevertheless decreed “was designed to pander to, titillate and shock the viewing audience.” After eight years of litigation, however, that penalty was thrown out as “arbitrary and capricious.”

But the FCC’s problem wasn’t just with the courts. The public had a quite different reaction to the “wardrobe malfunction” as well. Most people didn’t see the blink-and-you-miss-it moment that ended the Super Bowl halftime show, and those who did weren’t immediately clear about just what they had seen. Even inside the network control room at Reliant Stadium, amidst the managed chaos that accompanies any live broadcast, directors of the show turned to one another after witnessing the show’s climax and asked, “What was that? But the curiosity of the audience had been piqued. The “wardobe malfunction,” as it was later called by a hapless Justin Timberlake, was the most TiVoed moment in television history up to that point and the most searched event online according to Google.

It wasn’t as if the public was rising up in outrage so it could flood the FCC with complaints. That task would be left to Bozell’s PTC and other pro-censorship groups whose bread and butter was whipping up spam email campaigns to energize regulators and legislators. No, the viewing audience was more curious than outraged about this strange and unprecedented event. In fact, a nationwide poll sponsored by the Associated Press in the weeks after the Super Bowl revealed that eighty percent of respondents believed that the federal investigation was a waste of taxpayer dollars.

Therein lies the censor’s dilemma.

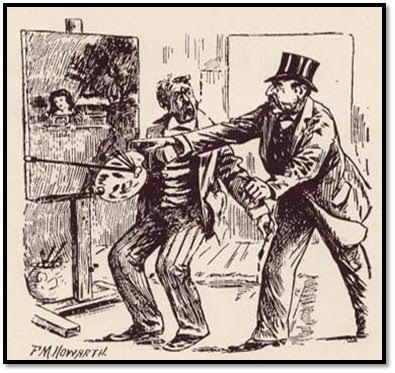

“Your Honor, this woman gave birth to a naked child!”

From The Masses, September, 1915. Public Domain.

“Don’t you suppose I can imagine what is under the water?”

From Life, January 18, 1888. Public Domain.

Censors may wield great power and enjoy political favor – for a time – and can ravage individual lives and reputations. But they also are the subject of popular derision and generally end up on the wrong side of history – in the United States, at least. This is why those who actively seek to suppress speech try vehemently to deny that their actions amount to “censorship,” and why they often feel beleaguered even as they marshal the power of the state to serve their purposes. Defensiveness pervades their occupation. Those who engage in the business of censorship have an inferiority complex for a reason – at some level they understand their enterprise is fundamentally un-American.

What do you mean, censorship?

Censorship is a word people use to mean many different things. Parents censor their children when they tell them not to make too much noise in the house or when they tell them they mustn’t say out loud that Aunt Maude is fat, or that Grandpa smells funny. But that isn’t the sort of censorship that is the primary focus of this book, as it does not implicate the law or state action. Nor is the use of private ratings systems, such as the Motion Picture Association of America’s ratings for movies or the Electronic Software Association’s ratings for electronic games. People often confuse such private editorial commentary with unconstitutional censorship.

There are those who claim to be censored by what they call “political correctness,” when their intolerant or racist rants are met with disdain and social ostracism. When L.A. Clippers owner Donald Sterling was banned from the National Basketball Association for life after he was recorded making mindlessly bigoted remarks to a young woman friend in 2014, it may have been an act of censorship, but it wasn’t illegal censorship. The First Amendment provides that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” It does not say “the NBA shall make no rules.” Same goes for the NFL when it decreed that players must either stay in the locker room or stand and salute during the national anthem (although the league has vacillated on this policy). For censorship to violate the Constitution, there must be an element of government action.

Such questions sometimes become complicated when public officials throw their weight around. Donald Trump launched his presidential campaign in 2015 with attacks on undocumented immigrants as rapists and murderers and defending his inflammatory rhetoric by saying he had no time for “political correctness.” As President, Trump has trashed any and all perceived critics, dredging up the Stalinist tag “enemy of the people” to describe established news organizations. Although he bristles at any suggestion that his own speech should be limited in any way, Trump also said we should “open up” the libel laws (whatever that means), that flag burners should be stripped of their citizenship, and that late-night comedy shows and the networks that air them should be investigated for lampooning him. Of course, it is one thing for a president to speak like a sixth grader who flunked civics, but when he acts to block critics from his official social media account, or revokes White House press credentials of reporters or news organizations he dislikes, that is another matter entirely. Courts have correctly understood such official actions as censorship, and have held not even the President can use his office in this way.

U.S. President Trump hosts workforce advisory board meeting at the White House in Washington. Reuters

The question of what constitutes censorship also has arisen in the context of social media platforms that restrict speech through their terms of service. Regardless of size, however, when online services such as Facebook or Google apply their editorial policies, they are not engaged in unconstitutional censorship, as there is no state action. To the contrary, enforcement of an editorial policy is the exercise of their First Amendment rights as electronic publishers. But the issue becomes convoluted when policy advocates or legislators try to insert the government into such decisions. Some argue that online intermediaries should be forced to identify and remove “hate speech” or “fake news” (as is done under European law), while some opportunistic politicians in the U.S. advocate regulating online platforms to prevent them from enforcing such policies on their own. A social media platform, like Twitter, is not a public forum that is subject to First Amendment rules, but a public official’s Twitter account that he uses as an extension of his or her office, is.

The ways in which free speech questions arise are myriad and complex, but what may constitute censorship in a legal sense is straightforward – the issue is whether governmental power is being used to limit or compel speech. Such censorship can take many forms, including government actions to suppress particular expression but also rules requiring speech, such as a pledge or loyalty oath. As a constitutional matter, compelled speech and coerced silence are indistinguishable. Thus, when the FCC requires broadcasters to air certain programs it deems to be in the “public interest” in order obtain a government license to operate a radio or television station, it necessarily raises First Amendment questions. A censor is one who seeks to exert control over the culture through law, based on the idea that he or she, speaking for the community, has a right to draw the boundary lines for speech. Few have the power that Comstock wielded, serving as both anti-speech activist and law enforcer. But those Comstock wannabes who merely advocate the use of state power to silence others certainly share his heart and soul.

The common thread

Ultimately, censorship results from the conviction that some forms of expression are so vile or dangerous they should be restricted, or so valuable they should be compelled. Censors claim the moral sanction to speak for the collective, either by enforcing “community standards” against evil expression or by mandating speech that they believe serves the “public interest.” They are willing to legislate their preferences and to brand as outlaws those who would transgress their standards. You can’t really argue taste – or, as the Latin maxim would have it, de gustibus non est disputandum, but at some times or places in America people have gone to jail – or lost their broadcast licenses – over such disputes.

The message of the censor is clear and unmistakable: I (or we) know the truth, and must control the ideas or influences to which you may become exposed to protect you from falling into error (or sin). Truth may be revealed by whispers from god, by political theory, by popular vote, or by social science, but once it has been determined, the time for debate is over. Anthony Comstock did not invent censorship, but his DNA may be found in the genetic code of every would-be censor who walks the earth. As Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy put it, “[s]elf-assurance has always been the hallmark of a censor.” In this respect, he echoed Mencken’s description of vice crusaders that “[t]heir very cocksureness is their chief source of strength.”

The arbiters of culture are sustained and emboldened by their moral fervor, but at least in this country they can never shake a certain defensiveness since they live in a community where the Supreme Court affirmed as far back as 1943 that one “fixed star in our constitutional constellation” is that “no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.” One might quickly add, as the Court did within a few years, that this principle applies equally to matters of taste and that “a requirement that literature or art conform to some norm prescribed by an official smacks of an ideology foreign to our system.” As Justice John Marshall Harlan would later write, “one man’s vulgarity is another man’s lyric.” Thus, in a free society the censor cannot claim moral superiority, no matter how sanctimonious he may be.

Just can’t get enough

Actress cards, featuring women exhibiting male clothing and behaviors, were frequent targets of19th-century censorship campaigns. Here, actress Annie Sutherland poses for a Virginia Brights Cigarettes campaign c. 1888. Part of the Jefferson R. Burdick Art’s Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The internal conflict is not just a question of law. There appears to be a psychological dimension to the censor’s dilemma as well. What can one say about the type of person who devotes his or her life to denouncing certain types of expression and advocating its prohibition while choosing a profession in which he immerses himself in it? Purity crusaders claim to hate the material they want to suppress and argue it will ruin all who are exposed, but invariably can’t get enough of it. They search it out, collect it, study it, categorize it, archive it, talk about it, and display it to others, all for the ostensible purpose of making such expression cease to exist.

Comstock created what he called a Chamber of Horrors – his personal collection of lewd publications and “obscene” objects – that he would show Members of Congress to persuade them of the need for his 1873 federal obscenity law. Over 120 years later, Senator James Exon crafted his “Blue Book” to illustrate early examples of Internet porn, which he showed to colleagues to persuade them of the need to restrict online “indecency.” Congress responded by adopting the indecency prohibitions of the Communications Decency Act by an overwhelming margin in 1996.

Activists of all political stripes surround themselves with the type of speech they believe must be suppressed for the good of others, yet mysteriously are immune to its dangerously toxic effects. Could it be that such people are drawn to their work because of the opportunity to spend countless hours communing with the forbidden? As Sydney Smith, a noted British writer and cleric of the nineteenth century once observed, “[m]en whose trade is rat-catching love to catch rats; the bug destroyer seizes upon the bug with delight; and the suppressor is gratified by finding his vice.” It is not beyond belief that censorship is an ultimate act of self-gratification, and that our rights are sacrificed on an altar of the censor’s guilty pleasure.

Morris L. Ernst, a co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, noted this phenomenon in his 1928 study of obscenity and the censor entitled To The Pure: “Recall those men who belong to vice societies but enjoy showing, of course in a scientific manner, postal cards of homosexual acts.” He concluded that examples of such public hypocrisy “are too multitudinous to permit a detailed inventory.” Ernst observed that Anthony Comstock was an “obvious psychopath” whose diaries provided “precious morsels for any psychiatrist” because his writings made it obvious “he suffered from extreme feelings of guilt because of a habit of masturbation.” This may help explain why Comstock devoted a lifetime to collecting, cataloguing, and destroying all that he found to be shameful.

A vast bipartisan conspiracy

“Progressives and conservatives are united in the common conviction that they know what speech should be banned (or required) and that their choices should be enforced by law; they only differ in their preferences.”

Because the urge to censor derives from personal preferences or policy positions, no political party or philosophy is immune from the impulse to suppress contrary views. One oft-expressed stereotype is that conservatives favor censorship while liberals oppose it, but one needn’t search long to find numerous counter examples, as later chapters will explore. Liberals and conservatives alike, regardless of how one might define those philosophies, appear to agree that the machinery of government can rightfully be used to restrict speech, provided the targeted expression is sufficiently vile (from their point of view) or insufficiently valuable (using their scale as a measure). The problem is, the competing factions never can seem to agree on which speech should be banned.

A common assumption is that conservatives want to censor sex, while liberals want to censor depictions of violence and “hate” speech, while both want to restrict speech about abortion – so long as it is the other side that gets muzzled. Veteran journalist and free speech advocate Nat Hentoff summed up the mindset quite nicely in his book Free Speech For Me But Not For Thee, noting that “the lust to suppress can come from any direction.” Hentoff credited to a fellow journalist the insight that censorship “is the strongest drive in human nature; sex is a weak second.”

Cartoon by Matt Wuerker

Some social conservatives seek to limit access to information about abortion (just as earlier generations sought to suppress discussions of contraceptives), while some progressives try to restrict “sidewalk counseling” and other efforts outside clinics to dissuade women from terminating their pregnancies. Both sides justify their actions in the name of public health and decry their adversary’s tactics as censorial. Liberals generally favor placing limits on political campaign expenditures and contributions, while conservatives tend to oppose them as a violation of free speech. But the roles switch when restrictions are imposed on providing “material support” (aka “contributions”) to organizations branded by the government as supporting terrorism (or, in earlier days, Communism). Liberals recoil at the courts’ increasing recognition of constitutional protection for commercial speech (unless it involves the commercial promotion of contraceptives), while conservatives (and some progressives) claim authority to ban or restrict sexually-oriented entertainment because it is “commercialized.”

These are generalizations, of course. Not all liberals think alike on these issues, just as conservatives may take different positions. The problem may lie in the left-right labels themselves, notwithstanding the polarization of our current political culture that resembles a giant game of “shirts versus skins.” The two sides divide into self-selected factions and reflexively oppose whatever the other team is proposing as the solution to society’s ills. But the one point on which most of the combatants in these political controversies agree is that they don’t want to be tarred as “censors.” Censorship is what the other side is doing. Those bastards!

Implausible deniability

Just as hypocrisy is the homage vice pays to virtue, as 17th-century French writer Francois de La Rochefoucauld put it, so is euphemistic evasion. George Orwell, in his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language, wrote that political euphemism “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give the appearance of solidity to pure wind.” He observed that “[d]efenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification.” “In our time,” Orwell concluded, “political speech and writing are largely [employed in] defense of the indefensible.” Updating Orwell’s example, genocide came to be known in the 1990s as “ethnic cleansing.”

The corruption of language for political ends is a central premise of Orwell’s fictional masterpiece, Nineteen Eighty-Four. In that novel he described the nation of Oceania in which the apparatus of government was divided between the Ministry of Truth, which concerned itself with news, entertainment, education, and the fine arts; the Ministry of Peace, which concerned itself with war; the Ministry of Love, which maintained law and order by torturing dissidents; and the Ministry of Plenty, which was responsible for economic affairs and rationing. Newspeak, the official language of Oceania, was designed to meet the ideological needs of the State. Its purpose, Orwell wrote, was “to make all other modes of thought impossible,” which was accomplished by eliminating superfluous words from the dictionary and stripping all remaining words of “unorthodox meanings.” These principles were the basis for the official slogans of the Party over which Big Brother presided:

War is Peace

Freedom is Slavery

Ignorance is Strength

Orwell’s vision would seem outlandish if nonfictional examples of language corruption were not so common.”America’s Mayor” (and later Trump consigliere) Rudolph Giuliani was seemingly channeling Big Brother when he said in a 1994 speech that “[f]reedom is about authority. Freedom is about the willingness of every single human being to cede to lawful authority a great deal of discretion about what you do.”

Giuliani at least was clear in saying he was all about control. Others obfuscate more (or at least are a little more artful about it). In 2017, officials at American University refused to approve a sorority fundraiser they believed may be insensitively “appropriating culture.” They were wrong about that, but couldn’t bring themselves to cop to the censor label. Instead, Colin Geeker, the school’s assistant director of fraternity and sorority life wrote to Sigma Alpha Mu to say “I want to continue empowering a culture of controversy prevention among [Greek] groups,” advising the sorority to “stay away from gender, culture, or sexuality for thematic titles.” Evidently feeling empowered by this exchange, Sigma Alpha Mu cancelled the fundraiser.

Public officials routinely use language creatively to expand their power. As a candidate, Donald Trump asserted that no one has greater respect for the First Amendment while simultaneously condemning reporters and advocating “opening up” the libel laws. He and his senior staff members label unfriendly stories as “fake news” while at the same time offering a different version of reality based on what they unblushingly describe as “alternative facts.” In this parallel universe, words simply don’t have the meanings they once did. These people would be right at home in Orwell’s Oceania.

Given the long history of misdirection by those seeking to avoid the appearance of misusing power, it is no wonder that euphemism is the weapon of choice among censors in America. Ever since Anthony Comstock gave censorship a bad name, his philosophical descendants have gone to great lengths to describe their actions as something else. The vehemence of their denials and rationalizations is a pretty reliable measure of the grip of the censor’s dilemma.

The law evolves

Supreme Court Associate Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes around 1924.Credit. Library of Congress

Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes identified the mindset of the censor early on. He wrote in 1919 that “[p]ersecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition.” But he ultimately realized that this impulse to censor, and the sense certainty that drives it, must be leavened with historical perspective: “When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas – that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.”

This insight came from Holmes’s dissent in Abrams v. United States, the fourth decision that year in which the Supreme Court upheld prosecutions of anti-war dissenters under the Espionage Act of 1917. That law made it a crime to cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty in the military or naval forces of the United States. An amendment to the law, the Sedition Act of 1918, prohibited “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about the United States government, its flag, or its armed forces or that caused others to view the American government or its institutions with contempt. These sweeping prohibitions on dissent begged courts to answer the question of what the framers of the Constitution meant when they wrote the First Amendment. And if the law’s suppressive language weren’t enough to force the question, the sheer number of prosecutions – nearly 2,000 during the Great War alone (and over a thousand convictions) – made it critical that the Supreme Court create doctrine governing freedom of speech.

There was little the Court could draw on from earlier precedents. In the few cases that had come up in preceding years, the Court was not quite sure what to make of the First Amendment. Among other things, it had allowed the deportation of “anarchists,” permitted the Post Office to exclude certain publications from the U.S. mail, upheld a state flag “misuse” law, as well as a law that prohibited any publication that tended to incite crime or disrespect for the law. In most cases the Court simply sidestepped First Amendment controversies by ruling that free speech issues were outside its jurisdiction, or by categorizing the behavior at issue as something other than “speech.” In a 1911 case, for example, it held that union advocacy of a boycott was a “verbal act,” not protected expression.

But the Court’s ability to avoid First Amendment questions came to an abrupt end with America’s involvement in World War I and the Espionage Act cases that followed. It was inevitable the issue would come to the Court, and in quick succession, it upheld convictions of members of the Socialist Party for circulating anti-draft pamphlets, a newspaper publisher for articles that criticized the war effort, and for a speech by socialist (and presidential candidate) Eugene Debs for purportedly obstructing the draft. Justice Holmes authored each of those opinions. But then he began to reconsider. The Abrams case was much like the others the Court had decided just months earlier. It involved the circulation of leaflets by socialists questioning the war. But Justice Holmes was now coming to believe that the “cure” of a criminal prosecution was worse than the disease. This time he dissented, writing that “Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country,” much less criminalize “publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man.” But Holmes’s main argument was not based on the practical consideration that speech should be allowed just because it is impotent and harmless. Quite to the contrary, he maintained that we must be “eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions we loathe and believe to be fraught with death” unless “an immediate check is required to save the country.”

He then posited his marketplace of ideas metaphor for the First Amendment. It was not that he believed free trade in ideas guaranteed truth necessarily would emerge; just that it provided the “best test” of truth over time compared to some “authoritative selection.” This notion, Holmes suggested, “is the theory of our Constitution.” He cautioned that it is “an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year if not every day we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge.” From this basic premise that flowed from Holmes’s pen in 1919, First Amendment law evolved through the twentieth century.

A 1906 illustration of Anthony Comstock, “village nuisance.” Public Domain.

But it didn’t happen immediately. Another dozen years would pass before the Supreme Court would begin to uphold First Amendment claims – one hundred and forty years after the Bill of Rights was ratified. From that point on, First Amendment law developed through a process of case-by-case adjudication, with each decision drawing on or distinguishing the reasoning of prior rulings. As a consequence, First Amendment law reflects the times in which it was crafted. Just as an archeologist may better understand modern society by studying prior civilizations on which it is built, those who want to grasp the American imperative of free expression – and our innate aversion to censorship as a people – should examine the many circumstances in which these principles were developed and applied.

Disputes involving radical politics as well as labor disputes underlay many of the cases the Supreme Court confronted in the 1930s and 1940s. The rights of minority religious groups like the Jehovah’s Witnesses gave rise to a series of cases through the 1940s and 1950s. During this period and continuing into the 1960s, the Red Scare and McCarthyism generated numerous cases involving academic freedom, loyalty oaths the general right to question political orthodoxy. The cultural and political upheavals of the 1950s through the 1970s led to a series of landmark cases that set the standards for doctrines involving defamation, public protest, and obscenity. In this sense, the development of the law of free speech is intertwined with the rise and fall of the Cold War, the civil rights movement, anti-war demonstrations, and general cultural changes. In more recent years, cases have extended legal protections for commercial speech and have subjected political campaign regulations to constitutional scrutiny.

It has been an evolutionary process that has trended toward greater levels of tolerance for – and legal protection of – divergent expression. And it is a level of tolerance that tends to mirror what society is prepared to accept. There are exceptions, of course, since evolution generally does not progress in a straight line. And it often takes years – and sometimes decades – for courts to catch up with the culture.

But the interconnected nature of legal and social attitudes toward free expression was well articulated by Justice Anthony Kennedy in a 2000 case, United States v. Playboy Entertainment Group, Inc.:

When a student first encounters our free speech jurisprudence, he or she might think it is influenced by the philosophy that one idea is as good as any other, and that in art and literature objective standards of style, taste, decorum, beauty, and esthetics are deemed by the Constitution to be inappropriate, indeed unattainable. Quite the opposite is true. The Constitution no more enforces a relativistic philosophy or moral nihilism than it does any other point of view. The Constitution exists precisely so that opinions and judgments, including esthetic and moral judgments about art and literature, can be formed, tested, and expressed. What the Constitution says is that these judgments are for the individual to make, not for the Government to decree, even with the mandate or approval of a majority.

This growing level of tolerance for free expression, and by extension, an inherent distaste for arbitrary authority, means that many current battles over free expression are being fought along the fringes of the culture war, and involve issues that expose fault lines in our polarized society. Current cases ask whether some types of expression are simply too offensive to merit the protection of the Constitution or too trivial to qualify for a First Amendment shield. They reframe the question posed by Justice Holmes in 1919 – whether “enough can be squeezed from these poor and puny anonymities to turn the color of legal litmus paper.”

This book does not seek to present a grand theory of freedom of expression, nor does it engage in the ongoing academic debate about how to interpret the First Amendment. Its purpose is more modest – to understand something about the nature of free speech by exploring the mind of the censor. The First Amendment may best be understood by examining what it was designed to prevent rather than by speculating about what it was intended to promote. And, quite apart from what the Framers may have intended originally, modern First Amendment doctrine developed as a response to episodes of suppression and the excesses of censors. What came from this may not be a perfectly consistent or coherent body of law, but it has produced increasing levels of protection against would-be censors as it continues to evolve.

The ensuing chapters explore various incarnations of censorship in American history, beginning with the rise and decline of Anthony Comstock, the nation’s first professional anti-vice crusader. His career set the standard, and for many, the rhetorical tone, for those seeking to condemn various forms of speech. Although all who follow in Comstock’s outsized footsteps try to claim moral superiority – characterizing the speech they would restrict as distasteful, trivial, valueless, or downright harmful – the plain fact is that the censor in a free society never has the moral high ground. The censor’s dilemma is that somewhere, down deep inside, he – or she – is painfully aware of it.

Tags