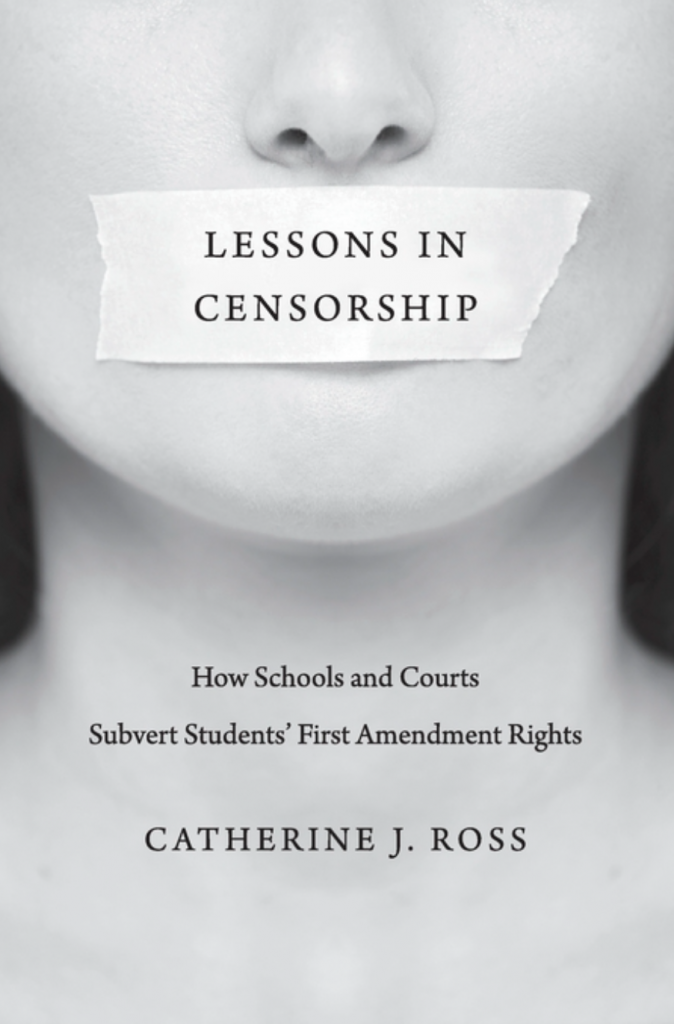

Ross’s book “highlights the troubling and growing tendency of schools to clamp down on off-campus speech such as texting and sexting and reveals how well-intentioned measures to counter verbal bullying and hate speech may impinge on free speech. Throughout, Ross proposes ways to protect free expression without disrupting education.” – Harvard University Press.

Catherine J. Ross is a professor at George Washington University Law School where she specializes in constitutional law (with particular emphasis on the First Amendment), family law, and legal and policy issues concerning children. Her book, Lessons in Censorship: How Schools and Courts Subvert Students’ First Amendment Rights (Harvard University Press, 2015) was named the Best Book on the First Amendment by Concurring Opinions’ First Amendment News, and won the Critics’ Choice Book Award from the American Education Studies Association. Professor Ross has been a co-author of Contemporary Family Law (Thomson/West) since the First Edition; the Fourth Edition was published in 2015.

Authors Share Excerpts on Free Speech:

Catherine J. Ross and Lessons in Censorship

Excerpted from Lessons in Censorship: How Schools and Courts Subvert Students’ First Amendment Rights by Catherine J. Ross, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2015 by The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Adaptation of 3,000 words from Introduction (pages 1-3, 6, 10), Chapter 5 (pages 150-154), Chapter 6 (pages 205-206), and Conclusion (pages 291-292, 299)

“You lose all constitutional rights once you enter a school building,” a school official in Suffolk County, New York, proclaimed in the spring of 2012. “You are not allowed to do this,” she asserted as she confiscated fliers from an indignant student who was protesting her friend’s five-day suspension. Layering censorship upon censorship, the episode had a surreal quality to it: the student whose plight prompted the pamphlets had been punished for voicing her opposition to bullying in a way the school deemed inappropriate.1

The seizure was as clueless as it was surreal. The official’s confidence that the Constitution stopped at the schoolhouse door contradicted decades of jurisprudence recognizing that minors too have constitutional rights, even in school. Unfortunately, the incident was hardly an aberration. A mix of ignorance about, indifference to, and disdain for the speech rights of students permeates society; parents, teachers, school boards, and even some judges exhibit these attitudes.

The speech at the core of Lessons in Censorship involves war and peace; civil rights; rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (“LGBT”) students; the Confederate flag; abortion; evangelical proselytizing; immigration; teasing and verbal bullying; sexting; personal prayer in public spaces; pushback against courses in tolerance that sometimes verge on thought reform; and more. No ideological or philosophical camp has been immune from censorship. Schools have stripped conservatives and progressives, secularists and the pious, of their right to speak. Disputes over the constitutional problem of student speech . . . capture an important dimension of everyday life in our schools, told in the stories of real students. . . .

The speech at the core of Lessons in Censorship involves war and peace; civil rights; rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (“LGBT”) students; the Confederate flag; abortion; evangelical proselytizing; immigration; teasing and verbal bullying; sexting; personal prayer in public spaces; pushback against courses in tolerance that sometimes verge on thought reform; and more. No ideological or philosophical camp has been immune from censorship. Schools have stripped conservatives and progressives, secularists and the pious, of their right to speak. Disputes over the constitutional problem of student speech . . . capture an important dimension of everyday life in our schools, told in the stories of real students. . . .

Three dramatic stories weave through my analysis of the troubled state of student speech rights in public schools today: the entanglement of law and culture wars, divisions on the Supreme Court over jurisprudence, and the frequent failure of schools to perform the critical function of fostering the free exchange of ideas so essential to preserving a vital democracy.

The first story chronicles the intrusion of the nation’s most volatile racial, religious, and sexual disagreements into the heart of our elementary, junior high, and senior high schools. Such battles go far beyond the state’s curricular choices about evolution, sex education, and ethnic studies that have garnered so much attention. The charged nature of these conflicts encourages school officials to censor expression to avoid controversy.

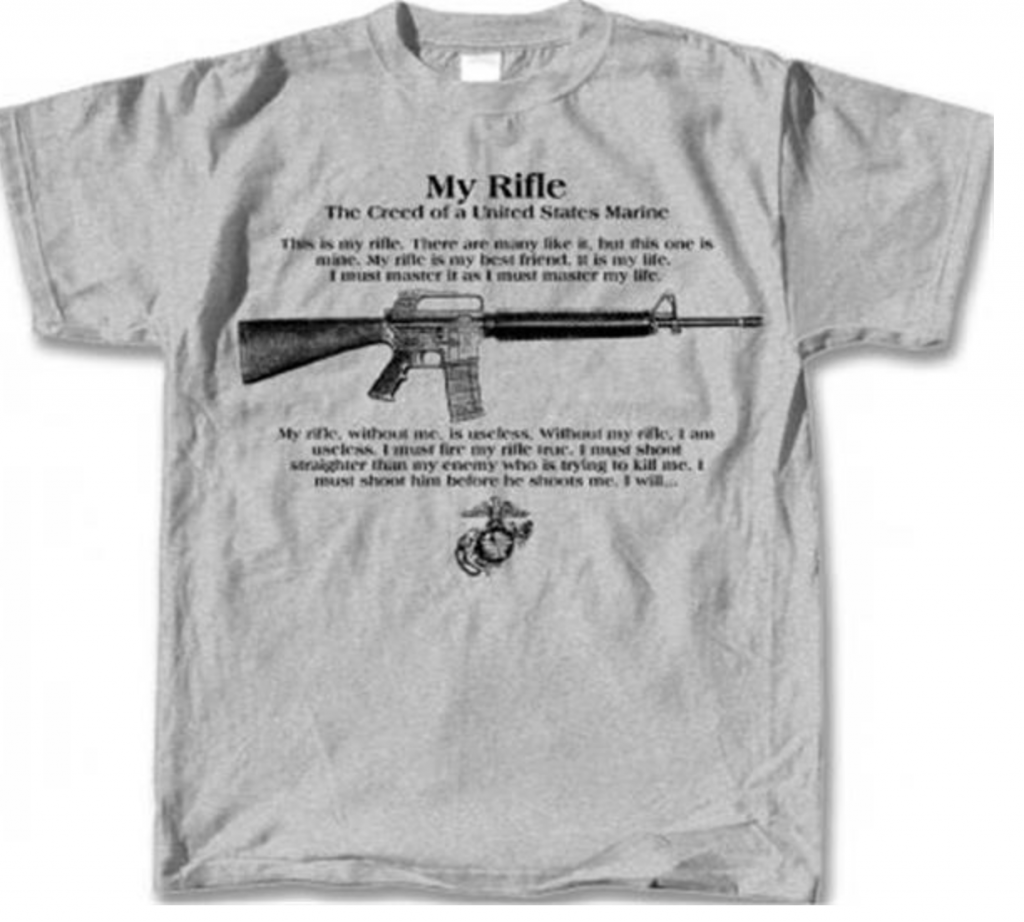

Consider just a sampling of such infringements. A high school student in Indiana who wanted to express support for U.S. troops overseas in 2005 was told he could not wear a T-shirt showing the Marines’ M-16 rifle and the text of the “Creed of the Marines,” an ode to the rifle. In Vermont, a middle school student was disciplined for wearing a T-shirt critical of President George W. Bush. Schools promoting tolerance have silenced religious students whose most profound spiritual beliefs compel objection to homosexuality. Officials have even told students they cannot talk about their religion together or study the Bible in their free time. Other schools prevent students from forming support groups for LGBT peers or wearing T-shirts declaring their sexual orientation.

Consider just a sampling of such infringements. A high school student in Indiana who wanted to express support for U.S. troops overseas in 2005 was told he could not wear a T-shirt showing the Marines’ M-16 rifle and the text of the “Creed of the Marines,” an ode to the rifle. In Vermont, a middle school student was disciplined for wearing a T-shirt critical of President George W. Bush. Schools promoting tolerance have silenced religious students whose most profound spiritual beliefs compel objection to homosexuality. Officials have even told students they cannot talk about their religion together or study the Bible in their free time. Other schools prevent students from forming support groups for LGBT peers or wearing T-shirts declaring their sexual orientation.

Mirroring fierce divisions in communities, heated fights over the proper balance between liberty and authority among Supreme Court Justices and other federal judges animate the second story. The central drama here has been the retreat from the judiciary’s expansion of the rights of children during the period from World War II through the war in Vietnam and the Supreme Court’s subsequent creation of an often incomprehensible taxonomy of rules that give different levels of protection to student speech depending on several variables.

Students pledging allegiance to the American flag with the Bellamy salute, March 1941

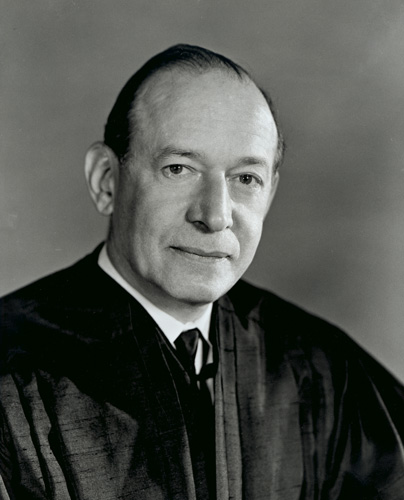

The Supreme Court’s 1943 ruling in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette provides . . . the opening scene of this legal drama . . . In Barnette, the Court ruled that students have the right to decline to salute the flag and summarized the important principles behind free speech in inspirational terms. The high point of the movement to guarantee students the protections of the Speech Clause—and a critical moment in this book—came a quarter century later in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, a 1969 case in which the Supreme Court held that students have the right to express their own views in school if their speech doesn’t cross specific lines. Tinker provided a special framework for evaluating when schools violate students’ affirmative right to speak that balances the constitutional rights of individuals with society’s need for schools that can fulfill the many demands we place on them.

In recent decades, successive Supreme Court benches, guided by increasingly conservative Chief Justices and composed of increasingly conservative majorities, have carved out a series of exceptions to Barnette’s principles and Tinker’s rules. First, the Court removed an undefined swath of “lewd” speech from Tinker’s protection. Second, and most powerfully, the Court allowed schools virtually unlimited discretion to censor speech it called “school-sponsored.” Finally, it granted schools dispensation to censor speech that appears to promote the use of illegal substances, which many readers will recognize as the “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” case.

Justice Abe Fortas wrote the majority opinion in Tinker

The multiplying categories of student speech, each of which has its own level of constitutional protection, have led some judges and law professors to question whether anything remains of Tinker’s robust vision of First Amendment rights for students. Even when schools and courts agree about which Supreme Court decision governs a controversy, the law may depend on where the student lives if the Supreme Court has not resolved the particular question at the heart of the dispute and the appellate courts disagree about what the Constitution requires. [The book provides a map of the United States showing the geographical division of the federal appellate courts.]

(above from pages 1-3)

* * *

Understanding that free expression is a bedrock of democratic governance reveals why the other stories matter. It is the starting point and the end point of all of the episodes in this book. In short, this is a story about the very meaning of democracy, not as an empty incantation but as a vibrant part of daily life.

Educators continually teach students the opposite lesson: that the First Amendment is a sham, something for the ages, but not for them. These counter-lessons register when a school superintendent prevents high school reporters from publishing a story about an environmental lawsuit pending against their school district, a matter of public record. And they register when a high school suspends a gifted art student and demands that she submit to a psychological examination after she displays a poster with the fictional theme “who killed my dog?”—part of a common pattern in which schools punish students for the content of fictional stories and poems. The idea of an all-powerful state is further reinforced when schools suspend students for sharing criticisms of teachers, coaches, or staff members with friends or for muttering a single curse word that is inaudible to peers. Increasingly, educators have extended their reach beyond the school into students’ private lives and even their homes, punishing students and referring them to law enforcement authorities based on digital communications sent from students’ own computers outside of school, including adolescent antics and web postings labeled as jokes. (page 6)

Justice Robert H. Jackson

None of the doctrinal developments since the 1940s has diminished the grandeur of Justice Jackson’s recognition in Barnette that “educating the young for citizenship” is essential to preserving a robust democracy. So is respecting the rights of the young. Nowhere, he insisted, is “scrupulous protection of constitutional freedoms” more important than in the nation’s schools “if we are not to strangle the free mind at its source and teach youth to discount important principles of government as mere platitudes.

“Material Disruption” Untethered

Material disruption constitutes the primary justification schools use when they constrain student speech under Tinker. Schools assert a fear that speech will lead to material disruption far more often than they allege that student expression threatens . . . serious violence [that schools may always cut short]. . .

[The] most significant challenge to Tinker arises from the efforts of some school officials to push the boundaries of “material disruption” beyond recognition . . . As the Eleventh Circuit explained, “some slight, easily overlooked disruption, including but not limited to ‘a showing of mild curiosity’ by other students, discussion and comment . . . , or even some ‘hostile remarks’ or ‘discussion outside of the classrooms by other students’” does not suffice to show a risk of material disruption.2 The elusive zone falls somewhere between such minimal and routine flurries of activity and. . .serious threats of violence . . .It is indisputably the judge’s job to assess the constitutional legitimacy of the school’s claim that “‘undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance’ transform[ed] into a reasonable forecast that a substantial disruption . . . will occur.” Lawyers and judges draw lines of this sort every day. And yet some commentators fear that the question of when speech “may be fairly characterized as ‘disruptive’” is just too difficult. One federal judge posited in 2010 that the notion of “disruptive” student speech “‘crosses into a constitutional gray area.’ ” “While simple in theory,” another judge observed sympathetically, “this standard is difficult to apply across the myriad possible disruptions faced by school administrators.”3

School officials must decide rapidly how to respond to political hyperbole, racially offensive speech, and speech supporting or condemning homosexuality, among other hot-button topics. Material disruption includes many situations that fall far short of danger to life and limb, and schools also sweep in many minor inconveniences that they regard as material interference with education. The courts have encouraged that tendency by failing to articulate the boundaries of material disruption more precisely.

School officials must decide rapidly how to respond to political hyperbole, racially offensive speech, and speech supporting or condemning homosexuality, among other hot-button topics. Material disruption includes many situations that fall far short of danger to life and limb, and schools also sweep in many minor inconveniences that they regard as material interference with education. The courts have encouraged that tendency by failing to articulate the boundaries of material disruption more precisely.

Over the years, a few principles have emerged that help officials to respond quickly when safety is at stake without worrying that they will be held legally accountable if their fears turn out to be unfounded. These principles, placed alongside judicial decisions about facts that fall on either side of the material disruption line, help to clarify what . . . Tinker [‘s material disruption test] means.

The most salient feature of the standard is that it was not designed to be easily satisfied. Tinker pointedly instructed school officials that “undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance” never justifies restrictions on student speech. Such speculative fears are “not enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression.” School officials, the Court explained, must be able to show “facts which might reasonably have led school authorities to forecast substantial disruption or material interference,” amounting to “something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint.” If the school can’t do that, prohibition or punishment of speech violates the student’s rights4.

* * *

The Supreme Court provided guidance by listing some potentially proscribable acts the Tinker protesters did not engage in. They weren’t “aggressive.” They did not lead “group demonstrations.” They “neither interrupted school activities nor sought to intrude in the school affairs or the lives of others” and caused “no interference with work and no disorder.”5

But as the paradigmatic cases receded in time and the Supreme Court signaled that Tinker no longer reigned as the only school speech doctrine, some school officials apparently abandoned any effort to explore what counts as disruption under the law. Schools tend to view demonstrations as inherently disruptive, especially when other students are in classes, and courts have quickly accepted the schools’ characterizations of protests as “near riots.”6 They seem to have lost sight of the school as a training ground for active citizenship, which may include fighting to make the law more just. (pages 150-154)

* * *

Howell High School logo

The seeming paradox of enforcing tolerance perfectly symbolizes an array of ironies stemming from the tension between free expression and the rights of others . . . . Never was that tension more sharply joined than in a Michigan high school on Anti-Bullying Day in 2010. The day is also known as “Spirit Day,” in recognition of LGBT teen- agers who have committed suicide. The Gay/Straight Alliance of Howell High School had received permission to post fliers about the event, but the school did not officially sponsor it. Teacher Jay McDowell donned a purple T-shirt with anti-bullying slogans on the designated day and devoted his economics class to a discussion of bullying. He showed a video about a student who had committed suicide after being bullied about his sexual orientation. McDowell asked a girl who was wearing a Confederate flag on her belt buckle to remove it. She did.7

Daniel Glowacki, a student in the class, voiced his concern that McDowell’s shirt and message discriminated against him and other Roman Catholics. Glowacki announced, “I don’t accept gays.”8

McDowell called Glowacki’s comment inappropriate. When Glowacki refused to modify his stance, McDowell told him to leave the classroom. Another student said he agreed with Glowacki, asked to be excused, and left.

When Glowacki complained, the school exonerated him and reprimanded his teacher. The school concluded that Glowacki had not caused any disruption and that McDowell had “‘modeled oppression and intolerance of student opinion.’” Students, the district correctly reminded McDowell, could not be disciplined for their beliefs. It gave McDowell “First Amendment training.”9

Despite this resolution of the dispute, the Glowacki family sued, alleging that Daniel’s rights had been violated and that his younger brother’s potential speech had been chilled. Applying Tinker, the court found that McDowell had discriminated against Glowacki’s viewpoint, interfering with the “‘robust political debate’” to which the nation is committed. It rejected the school’s argument that Glowacki’s statement interfered with the rights of a gay student in the class because “it was not a bullying remark” addressed to a specific individual. There was, the court explained, “no indication” that Glowacki “threatened, named or targeted a particular individual.”10

Teaching tolerance, the court directed, is best achieved in an atmosphere that shows how divergent views can be expressed “‘in a civilized and respectful manner’ ” and “‘includes the tolerance of even the most intolerant or disagreeable viewpoints.’ ”11 Tolerance can—and should—be taught, but those who teach it must personify their own lesson, staying within the limits the First Amendment imposes.

Ultimately, the students who remained in the classroom after Glowacki left may have framed the issue most eloquently: Against the teacher’s insistence that “‘a student cannot voice an opinion that creates an uncomfortable learning environment for another student,’ ” the class pressed, “Why didn’t” the two students who left the room “have free speech?”12 (pages 205-206)

* * *

Many lower court judges—again from every point on the political and philosophical spectrum—have explicitly linked the realization of student speech rights to transmitting democratic habits and the skills that foster citizenship. As Judge Frank Easterbrook explained, educators must take advantage of the teaching moments unavoidably generated by protected speech because schools are obligated to explain why the Constitution safeguards expression some people may not want to hear. If schools cannot teach the foundations of speech rights and help students distinguish private from official speakers, he ruminated, “then one wonders whether the . . . schools can teach anything at all.” To Easterbrook, the bottom line could not be simpler: “[E]ducating the students in the meaning of the Constitution [is] what schools are for.”13 Nothing could be more indispensable to the union we continually strive to perfect. (page 299)

___

1“Long Island Student Suspended for Fictional Video about Bullying,” www.foxnews.com (accessed 3/11/14)

2Holloman v. Harland, 370 F.3d 1252 at 1271-1272 (11th Cir. 2004) (internal citations omitted).

3J.S. v. Blue Mountain Sch. Dist., 650 F.3d 915, 930 (3d Cir. 2011) (en banc), cert. denied, 132 S. Ct. 1097 (2012); Cox v. Warwick Valley Cent. Sch. Dist., 2010 WL 6501655, at *14; Dariano v. Morgan Hill Unified Sch. Dist., 822 F. Supp. 2d 1037, 1042 (N.D. Cal. 2011) (citing Karp v. Becken, 477 F.2d 171, 174 (9th Cir. 1973)), aff’d, 745 F. 3d 354 (9th Cir. Feb. 27 2014), amended by 767 F. 3d 764 (9th Cir. 2014), cert. denied, 83 U.S.L.W. 3762 (U.S. March 30, 2015) (No. 14-720).

4Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. at 503,508, 509 (1969) (quoting Burnside v. Byars, 363 F.2d 744, 749 (5th Cir. 1966)).

5Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. at 508, 514. The Supreme Court in Tinker recognized that organized demonstrations on campus might be inherently disruptive, though it made clear that disapproval of demonstrations without more did not suffice to justify outlawing them. Ibid., 509 n. 3.

6Brown v. Cabell Cnty, Bd. Of Educ., 714 F. Supp. 2d 587, 590 (S.D. W. Va. 2010); Madrid v. Anthony, 510 F. Supp. 2d 425 (S.D. Tex. 2007); Pangle v. Bend-Lapine Sch. Dist., 10 P. 3d 275, 286-287 and 10 P. 3d at 289, 290-291 Bend-Lapine Sch. Dist., 10 P. 3d 275, 286-287 and 10 P. 3d at 289, 290-291 (Armstrong, J., dissenting in part) (vulgarity in an underground newspaper does not threaten disruption).

7Glowacki v. Howell Public Schools, No. 2:11-cv-15481, 2013 WL 3148272 (E.D. Mich. 2013).

13Hedges v. Wauconda Sch. Dist., 9 F.3d 1295, 1300, 1299 (7th Cir. 1993) (Easterbrook, J.).