Ironies and Complications of Free Speech, a collection of the best writing from the Free Expression Policy Project (2001-2017), covers topics that range from loyalty oaths, the Mohammed cartoons, and junk science to the FCC’s censorship of “indecency” on the airwaves, Janet Jackson’s infamous “wardrobe malfunction” at the 2004 Super Bowl, and copyright battles involving James Joyce, Tennessee Williams, and Google’s attempt to ban the use of its name as a verb. Through its stories of events and controversies, the book provides a primer on a range of tricky First Amendment issues.

Marjorie Heins is past director of the Free Expression Policy Project (FEPP) and the American Civil Liberties Union’s Arts Censorship Project. She is the author of six books, including Priests of Our Democracy: The Supreme Court, Academic Freedom, and the Anti-Communist Purge, which won a Hugh M. Hefner First Amendment Award in in 2013; Not in Front of the Children: “Indecency,” Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth, winner of the American Library Association’s 2002 Award for Best Published Work in the Field of Intellectual Freedom, and most recently, Ironies and Complications of Free Speech. She has taught at New York University, the University of California/San Diego, Boston College Law School, and the American University of Paris.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Authors Share Excerpts on Free Speech:

Marjorie Heins and Ironies and Complications of Free Speech

Excerpted from Ironies and Complications of Free Speech by Marjorie Heins

Copyright © 2018 Marjorie Heins.

From the Introduction

The Free Expression Policy Project had its roots in the 1990s, when I served as director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Arts Censorship Project. In this job, I soon learned that the primary target of censorship in the United States is the subject of sex. There is something called “obscenity” that has long been assumed to lie outside the First Amendment’s sweeping command that Congress shall make “no law … abridging the freedom of speech.” The big problem has always been how to define this “obscenity” exception to the First Amendment. Courts have tried various formulas over the years, without success: every definition has been impossibly vague and subjective. Justice Potter Stewart was honest enough to acknowledge this in 1969 when he simply wrote: “I know it when I see it.”1

In other words, “obscenity” is a legal concept, yet it is impossible to define with precision. But that was only one of the ironies I confronted in my work at the ACLU. There was also the more fundamental question: why is some subcategory of speech about sex (that is, “obscenity”) unprotected by the First Amendment in the first place, while other categories that also occasion moral disapproval, such as racist hate speech and grotesquely violent entertainment, are fully protected?

This irony became particularly acute in the 1990s and 2000s, when media violence was at least as hot a target of censorship efforts as were explicit sexual images. Several states and localities passed laws restricting minors’ access to violent video games. In the end, all of these anti-violence laws were struck down—as I chronicle in my commentary in this volume, “Why Nine Defeats Haven’t Stopped States From Passing Video Game Censorship Laws.” For the most part, the courts found that the laws were just too vague: they had the same problem of defining what it was the legislators thought dangerous as obscenity laws have always presented. That is, they didn’t put people on fair notice of what was prohibited. Excessive vagueness has not proved fatal to obscenity laws, but, ironically, it has proved fatal to laws restricting media violence. . . .

From “The Strange Case of Sarah Jones”

Jan. 24, 2003

Of all the odd “indecency” rulings that the Federal Communications Commission has issued over the years, the ongoing [2003] case of Sarah Jones and her rap poem “Your Revolution“ is the most deeply suggestive of how censorship operates in America.

As many commentators have remarked, Jones’s poem is explicitly feminist, deeply political, and a powerful critique of misogynist messages in both hip hop and rock music. (It’s a remix of and response to Gil Scott-Heron’s famous spoken-word piece, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.”) For the FCC to brand this work as indecent and essentially ban it from the airwaves—as it did in May 2001 by imposing a $7,000 fine on the radio station that played it—betrays both the discriminatory nature of American censorship and the unwillingness of those in power to appreciate an artwork and a message that has particular relevance for young African American women.

Jones’s rap poem, admittedly, has racy language. It starts: “Your revolution will not happen between these thighs,” and continues:

The real revolution ain’t about booty size

The Versaces you buys

Or the Lexus you drives …

Your notorious revolution

Will never allow you to lace no lyrical douche in my bush

… Your revolution will not be you smacking it up, flipping it or rubbing it down

Nor will it take you downtown, or humping around …

It’s precisely the free (and imaginative) use of sexual language here that makes the rap empowering. As the DJ who played the poem at Portland, Oregon’s public radio station KBOO, said: “Jones’s song is inspirational. It says it’s cool, you can be in the hip hop game, but you don’t have to be no ‘ho.”2 . . .

The origin of the FCC’s odd power to censor the airwaves goes back to the beginning of broadcasting, when it was necessary for some authority to assign different frequencies to different broadcasts so that their signals did not interfere with each other. Because of this initial need for licensing, and because the airwaves were thought to be a public trust, it was assumed that government has more power over broadcasting content than it has over newspapers or books. When the FCC started to assert this power in the 1930s, its targets were such terms as “damned” and “by God,” as used by a radio orator. By the 1960s, the commission was still so prudish that it found wordplay such as “Bloomersville” (for Bloomville) to be punishable, and refused to renew the license of the offending radio station3 . . .

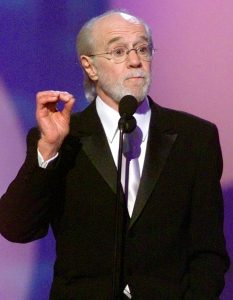

In the famous “seven dirty words” case, the agency [ruled] on a complaint about comedian George Carlin’s famous “Filthy Words” monolog, which hilariously satirized taboos surrounding common four-letter words. The FCC said it would ban as indecent any language, no matter what its artistic value, that airs when a child might be listening, and that describes sexual or excretory activities or organs in a manner that’s “patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards for the broadcast medium.” The offending radio station this time was Pacifica’s New York affiliate, WBAI. . .

Comedian George Carlin/REUTERS

Pacifica sued to challenge the FCC’s ruling, and won in the federal court of appeals, but in 1978, the Supreme Court reversed, and upheld the FCC’s power to censor broadcasting under the indecency standard. The primary justification, wrote Justice John Paul Stevens for the Court’s narrow 5-4 majority, was to protect kids, who the justices simply assumed would be “adversely affected” by George Carlin’s bawdy language. Moreover, said the Court, the government wasn’t really banning vulgar speech; it was only requiring that it be aired late at night, when children supposedly aren’t listening 4. Which is a bit like telling an artist to exhibit his work in a closet, or a writer that her book can only be sold after 10 pm.

Fast forward to 2001, when the FCC applied its broad, subjective indecency standard to another nonprofit, public radio station, for playing Jones’s “Your Revolution.” Language that’s funny, inventive, and deeply resonant with inner-city girls and women was condemned as “patently offensive” and “designed to pander and shock.” The FCC’s cursory decision ignored the value of Jones’s poem, and brushed aside station KBOO’s explanation of the political meaning and cultural context of the work 5…

. . . .

Update: On February 20, 2003, faced with a possible loss on appeal, the FCC reversed itself and decided that “Your Revolution” is not indecent after all. Thus, it managed to avoid judicial review of its unbridled discretion to impose its conservative cultural standards on community radio.

From “Disney, Media Giants, and Corporate Control”

May 21, 2004

Here is a First Amendment quiz. Which is the biggest threat to free expression in America today:

(1) The Walt Disney Company’s announcement two weeks ago that it will not permit its Miramax subsidiary to distribute Michael Moore’s film Fahrenheit 9/11. 6

(2) Disney’s alleged reason for the ban: fear that Florida Governor Jeb Bush will punish Disney if it distributes the film, by undermining lucrative tax deals for Disney theme parks.

(3) Ownership of ever-larger chunks of our culture by media conglomerates such as Disney.

If you guessed number 3, you are right.

Michael Moore/REUTERS

Michael Moore will find another distributor for Fahrenheit 9/11. In fact, last week Disney announced that it would sell the rights to Miramax founders Bob and Harvey Weinstein, so that they can arrange for another distributor. And Moore’s expert orchestration of the news of Disney’s decision, as well as his own well-deserved reputation as a trenchant critic of U.S. policy and culture, almost guarantee that a distributor will be found.

Disney’s alleged reason for its decision is more troubling than the decision itself. The likelihood that a political official (here, Jeb Bush) would retaliate against a taxpayer (here, Disney) for communicating information and ideas distasteful to the official is, perhaps, just a cynical recognition of political realities. But it would be unconstitutional for Governor Bush to manipulate his state’s tax policies in this fashion, and for good reason.

Protecting speech critical of the government is a core function of the First Amendment. If political officials can punish such criticism by withdrawing tax breaks or other benefits, then the result will be to suppress expression that is the basis of democracy. For this reason, courts have consistently ruled that it is unconstitutional for government officials to wield their power to retaliate against unwelcome speech.

By contrast, censorship by private corporations generally doesn’t create First Amendment problems. Disney and other mega-corporations have the right to decide which of the projects owned or generated by their many affiliates and subsidies they want to publish, broadcast, or distribute, and which (such as Fahrenheit 9/11) they want to quash. Technically, there is no First Amendment violation when Disney censors Michael Moore, or—to take another of numerous recent examples—when Viacom, whose CEO supported George W. Bush for president, refused to air independent political advertisements, including a critical ad by MoveOn.org during the Super Bowl broadcast. 7

Why, then, is censorship by private media corporations arguably the gravest threat to free expression in the U.S. today? Because as these companies grow ever bigger, the ability to decide what news, information, and political commentary most Americans will hear becomes concentrated in fewer hands. The formerly independent Miramax is now controlled by Disney. Independent book publishers have been swallowed up by corporate conglomerates like Bertelsmann and Viacom. 8

Most critically for democracy, the public depends on the media to uncover political malfeasance—including, most recently, the criminal conduct of the American military at Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad. If this essential function is concentrated in the hands of a few media powerhouses that are too cozy with those in power, we lose access to the information that we need to govern ourselves.

As the Supreme Court explained more than fifty years ago, a democracy cannot function well without “the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources.” 9 Whether the issue is Disney’s censorship of Moore in order to curry favor with President Bush’s brother or Viacom’s suppression of MoveOn.org for similar reasons, these events are only worrisome if Disney and Viacom are powerful enough to control the information and ideas that reach most Americans.

. . .

From “You Can Play Fantasy Baseball Without a License, But Can You Google It?”

Aug. 16, 2006

Two controversies in the past week highlighted the lengths to which some folks will go in trying to control language and information. The first involved that venerable American sit-down sport, fantasy baseball; the second concerned a newer, but even more popular pastime, “googling” on the Internet.

On August 8, 2006, U.S. Magistrate Judge Mary Ann Medler ruled that the Major League Baseball Players Association and its interactive media arm, called Major League Baseball Advanced Media, can’t stop fantasy game Web sites from using baseball players’ names, batting averages, and other statistics. The Players Association has long insisted that it has the right to license (or not) fantasy baseball games.

The C.B.C. Distribution Company, maker of fourteen such games, had filed suit asking for a declaratory judgment that it does not need a license. Magistrate Medler agreed, writing in her decision that both the players’ names and their statistics are in the “public domain”—readily available in newspapers and other media. 10

The decision turned on the “right of publicity” recognized in the laws of 28 states. . . . The right of publicity gives celebrities control over the use of their identities for commercial purposes such as advertising. For example, it prevents companies from using a celebrity’s name or photo to sell a product without the celebrity’s consent (which usually involves a large infusion of dollars for the endorsement). One famous case involved the “Here’s Johnny” Portable Toilet company—a clever pun, but one that TV personality Johnny Carson did not appreciate. (“Here’s Johnny” was the famous tag line on Carson’s late-night show.) The court held in that case that the potty company had unlawfully exploited Carson’s identity to obtain a commercial advantage. . . 11

Some might find it surprising that a fantasy game company found it necessary to go to court to establish its right to use publicly reported statistics. But the world of intellectual property is not always logical. What may seem obvious and commonsensical may not necessarily be the law; and even if the law favors the free speech side of the debate, industry practice, including the in terrorem effect of “cease and desist” letters, often squelches expression. 12 Kembrew McLeod, in his book Freedom of Expression®, and David Bollier in Brand Name Bullies, give hundreds of examples of questionable assertions of corporate control over common words, names, and images. 13

Google/REUTERS

An equally dubious example of industry overreaching is Google’s attempt to suppress the new verb “to google.” As reported in an August 14, 2006 article in the British newspaper The Independent: “Search engine giant Google, known for its mantra ‘don’t be evil,’ has fired off a series of legal letters to media organisations, warning them against using its name as a verb.” 14

According to The Independent and to a number of blog sites that picked up the story, Google wants to stop its name from entering the language as a verb because once the name becomes “generic,” it can no longer be protected by trademark law. Hence, the term “genericide” for what would seem on the surface to be a stroke of luck: a brand becomes so popular that its name substitutes for the product or process itself. Historic examples include “Xerox,” “Kleenex,” and “band-aid.”

Actually, Google has been sending cease and desist letters since 2003, when it tried to stop the lexicography site Wordspy from defining “google” as a verb synonymous with “search.” 15 Accompanying that letter was a circular giving examples of proper and improper uses of the term, according to Google. This circular, which became the subject of understandable mockery in the blogosphere, attempts the impossible job of dictating how language should evolve. To wit:

Appropriate: “He ego-surfs on the Google search engine to see if he’s listed in the results.”

Inappropriate: “He googles himself.”

and

Appropriate: “I ran a Google search to check out that guy from the party.”

Inappropriate: “I googled that hottie.” 16

Shortly after the Wordspy episode, Google tried to persuade the publishers of the Oxford English Dictionary not to list its trademark as a word, but the effort was ultimately unavailing. According to Wikipedia, “The verb ‘Google’ was officially added to the Oxford English Dictionary on June 15, 2006, and to the eleventh edition of the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary in July, 2006.” . . . 17

1. Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 197 (1969) (concurring opinion). The Supreme Court in Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15, 24-25 (1973), announced a three-part definition of obscenity: “whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest”; whether the work “depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

2. Deena Barnwell, quoted in Chisun Lee, “Counter Revolution,” Village Voice, 6/20-26/2001.

3. See Marjorie Heins, Not in Front of the Children: “Indecency,” Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth (2007), 90-93.

4. Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation, 438 U.S. 726, 750 (1978).

5. In the Matter of the KBOO Foundation, File No. EB-00-IHD-0079 (May 14, 2001).

6. Jim Rutenberg, “Disney is Blocking Distribution of Film That Criticizes Bush,” NY Times, 5/5/2004.

7. Fairness and Accuracy in Media, “Viacom Blocking Independent Political Ads,” 10/18/2004; Leonard Hill, “The Hijacking of Hollywood,” in News Incorporated (Elliot Cohen, ed., 2005), 224.

8. Free Press, “Media Ownership Rules,” http://www.freepress.net/rules/page. php?n=fcc (accessed 2004); and www.freepress.net generally.

9. Associated Press v. United States, 326 U.S. 1, 20 (1945).

10. C.B.C. Distribution Marketing v. Major League Baseball Advanced Media, 443 F. Supp.2d 1077, 1091 (E.D. Mo. 2006).

11. Carson v. Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets, Inc., 698 F.2d 831 (6th Cir. 1983).

12. See Marjorie Heins & Tricia Beckles, Will Fair Use Survive? Free Expression in the Age of Copyright Control (Free Expression Policy Project/Brennan Center for Justice, 2006), 4.

13. Kembrew McLeod, Freedom of Expression®: Resistance and Repression in the Age of Intellectual Property (2007); David Bollier, Brand Name Bullies: The Quest to Own and Control Culture (2006).

14. Stephen Foley, “To google or not to google? It’s a legal question,” The Independent, 8/14/2006.

15. Email from Wordspy manager Paul McFedries to the American Dialect Society mailing list, quoting the text of Google’s letter, http://listserv.linguistlist.org/cgi-in/wa?A2=ind0302D&L=ads-l&P=R2450 (accessed 2006).

16. See Frank Ahrens, “So Google Is No Brand X, but What Is ‘Genericide’?,” Washington Post, 8/5/2006, D01; “This word just in…,” posted by Doug, 7/10/2006, http://xooglers.blogspot.com/2006/07/this-word-just-in.html (accessed 2006) (both quoting the Google memo).

17. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google.

Heins discusses the publication of her new book in KKFI 90.1’s Law and Disorder podcast. Listen