Does the First Amendment Protect Provocateur Alex Jone From Libel Suits

Alex Jones and his website Infowars made repeated claims that the 2012 murder of 20 children and six adults at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut was a “giant hoax,” possibly instigating a number of his followers to harass the families of the victims. Does the First Amendment protect Alex Jones’ speech?

By the staff of First Amendment Watch and 1791 Delegates

Download a PDF of this Teacher Guide

Objectives

- Examine the libel law requirement for intentional or reckless falsehood, and analyze how it applies to the statements made by Alex Jones.

- Assess the First Amendment protection of opinion, and analyze whether it applies to the statements made by Alex Jones.

- Explain the First Amendment protection of rhetorical hyperbole, and analyze whether it applies to the statements made by Alex Jones.

Contents

FIRST AMENDMENT WATCH AT NEW YORK UNIVERSITY documents threats to constitutionally protected freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and petition— rights that are critical to self-governance.

Introduction

Issue #1 Public and Private Figures

Issue #2 Intentional or Reckless Falsehood

Issue #3 Is Opinion a Defense?

Issue #4 Is Rhetorical Hyperbole a Defense?

Resources

Glossary

Introduction

Defamation suits are a potential remedy for people whose reputation has been harmed by false statements. In today’s politically charged environment, a number of high-profile libel suits have been filed as a result of public controversies. One of these involves the parents who suffered the trauma of losing their children to a mass murderer. Their lawsuits against conspiracy theorist Alex Jones provides a compelling case study for teaching defamation law across the curriculum.

The Sandy Hook Massacre

On the morning of December 14, 2012, 20-year-old Adam Lanza used a .22-calibre rifle to shoot and kill his mother while she was sleeping. He then drove his mother’s car five miles to Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. He entered two first-grade classrooms and used a semiautomatic Bushmaster AR-15 assault rifle to murder 20 children, ages six and seven years old, and six women who worked at the school. Lanza then killed himself with one of two handguns he brought with him. The Newtown massacre became one of the deadliest school shootings in American history.

The Sandy Hook massacre, along with a string of other mass shootings, brought further attention to the national debate over government regulation of firearms. Despite then-President Barack Obama’s efforts, Congress failed to renew the legislation that it passed in 1994 to ban semiautomatic assault rifles and large-capacity magazines, and also failed to pass background-check legislation.

A heart is emblazoned with crosses to commemorate the 26 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting victims in Sandy Hook village in Newtown, Connecticut December 13, 2013. Adam Lanza REUTERS/Carlo Allegri

The Seeds of Disinformation

Meanwhile, conspiracy theorist Alex Jones used his media platforms, Infowars and PrisonPlanet.com, to spread falsehoods about the Sandy Hook massacre for nearly five years to his 2.7 million monthly viewers and 2.3 million YouTube subscribers. Jones’ followers, motivated by his conspiracy theories, harassed and threatened the families of the victims. One such follower, Wolfgang Halbig, a contributor to Infowars, hounded and threatened the parents of the victims. As a result of these false claims and the harm the grieving families experienced, Alex Jones and Infowars have been the subject of multiple defamation lawsuits.

Four primary First Amendment questions arise from these lawsuits:

• How do the courts determine who is a public figure and who is a private person?

• What is needed to prove intentional or reckless falsehood?

• Could Alex Jones prevail when using the First Amendment opinion defense?

• Could Alex Jones successfully use the First Amendment defense of rhetorical hyperbole?

First Amendment Issue #1: Public Officials, Public Figures, and Private Figures

Neil Heslin and Scarlett Lewis, parents of Jesse Lewis, 6, who was killed in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Sandy Hook, Connecticut December 9, 2013. REUTERS/Lucas Jackson.

The first issue to address in a defamation case is to determine whether the plaintiffs, in this case the Sandy Hook families, should be considered public officials, public figures, or private persons.

In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Supreme Court ruled that plaintiffs must prove that a defamatory statement is false. But even a false statement may be protected expression; plaintiffs must also prove that the false statement was published with fault. The level of fault to be proven depends on the status of the plaintiff. Is the plaintiff a public official, public figure, or a private person?

The lawyers for the Sandy Hook parents argued in court that they “are private individuals and are neither public officials nor public figures.” If the parents are indeed private persons, they would have an easier time winning their defamation suit.

Public Officials and Public Figures

Public officials and public figures have the toughest burden of proof because they have voluntarily assumed highly influential positions in society, and therefore their activities should be the object of continual scrutiny. Critics need substantial protection from libel suits or they will be chilled from providing rigorous coverage. Also, public officials and public figures can command the attention of the media to counter defamatory statements made about them without resorting to the courts for libel suits.

Public officials include a broad array of government officials. The Supreme Court explained in Rosenblatt v. Baer (1966) that a public official includes “those among the hierarchy of government employees who have, or appear to the public, to have substantial responsibility for or control over the conduct of government affairs.”

The Supreme Court has created two types of public figures. One category is the “all-purpose” public figure. These are most likely famous people—they occupy “positions of such persuasive power and influence that they are deemed public figures for all purposes. . . . They invite attention and comment,” Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974). The second category is “limited-purpose” public figures. These are not famous people. They are typically private citizens who have “thrust themselves to the forefront of particular controversies in order to influence the resolution of the issues involved,” Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. This might be, for example, a person who steps forward to try to influence debate about a tax or school issue in their community.

Given these considerations, public officials and public figures are required to prove a high level of fault in order to win. In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, the Court ruled that these plaintiffs must prove by “clear and convincing evidence” that the defendant published a false, defamatory statement with “actual malice”—that is, with knowledge of falsity or with reckless disregard for whether it was true or false. An intentional falsehood is essentially a fabrication. Reckless disregard for the truth applies when the speaker had a high degree of awareness of probable falsity, or entertained serious doubts that it was true, and published anyway.

Private Persons

On the other hand, private individuals do not assume positions of influence, and so there is much less of an imperative for the media to cover their activities. They also have less access to the media to rebut defamatory information about them. As a result, private figures enjoy a greater claim to protection from defamatory falsehoods, and the barrier to winning a libel suit is easier to surmount. Generally, they must prove that the false statement was published with negligence—that is, with a lack of due care under the circumstances. This negligence standard is much easier for a plaintiff to prove than a standard of intentional falsehood or recklessness. It’s the difference between mere carelessness and a fabrication.

Discussion Questions

1. Why did the U.S. Supreme Court in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan make it much more difficult for public officials and public figures to win libel suits than for private persons?

2. How does the Sullivan decision apply to the Sandy Hook plaintiffs? Do you think the Sandy Hook families should be considered by the courts public or private figures? What are the arguments for and against?

3. Compare and contrast the intentional falsehood and negligence standards. What distinctions can be made between “reckless regard for the truth” and “lack of due care”?

The activities in this guide assume that the plaintiffs are public figures. Why? This decision is not intended to give legitimacy to Alex Jones’ false claim that the families were hired by the federal government to serve as “crisis actors,” which if true might make them into limited-purpose public figures. Rather, the purpose of this exercise is to use an assumed public figure status to help students fully understand the complexities of how a plaintiff must satisfy the highest level of fault in defamation law. It is a difficult level of fault to prove, and deliberately so in order to protect public discussion about important issues and the people who take part in them.

Intentional or Reckless Falsehood

If any of the Sandy Hook plaintiffs are considered to be limited-purpose public figures, they would have to prove the actual malice standard. That is, they would have to prove by clear and convincing evidence that Jones published with knowledge of falsity or with reckless disregard for the truth.

“Knowledge of falsity,” or intentional falsehood, might be the more straightforward of the two. The plaintiffs look for evidence that the defendant knew the truth, but decided to ignore it and instead lie and fabricate a narrative of his own. The evidence might come from the defendant’s own work materials including notes, drafts, and correspondence, or from the public availability of facts established beyond dispute by investigators.

“Reckless disregard for the truth,” is something short of actual knowledge of falsity. As the courts have described it, reckless disregard involves the defendant publishing a false report despite having a high degree of awareness of probable falsity, or having entertained serious doubts as to the truth. Reckless disregard is much more serious than, for example, the careless mistake of forgetting to return a phone call or miscopying someone’s name from a police report. Reckless

disregard might involve complete reliance on a single source whose veracity is highly questionable, or going entirely with one version of a story when there is compelling evidence of contradictions and other explanations.

Apply the Intentional Falsehood Standard

Screenshot taken from a video-tapped deposition with Alex Jones taken by attorney Mark Bankston of Kaster Lynch Farrar & Ball, LLP. (Kaster Lynch Farrar & Ball LLP/ YouTube)

We don’t have access to Alex Jones’ notes or other work materials. But it’s possible to compare his denial that the massacre took place—and his assertions of a coverup and worse—against the verified facts that were added over time to the public record by law enforcement, eyewitnesses, forensic investigations, death certificates, medical records, and the like.

- Introduce evidence presented in courts: Use Table 1 and Table 2 to summarize the evidence that the families used in their complaints to make the case that Alex Jones published intentional and reckless falsehoods and to document the harm they faced as a result. Pose this question: Given what we know about Sandy Hook and Alex Jones’ statements about the massacre, do the statements made by Jones bolster the parents’ defamation claims?

- Watch “Key moments from Alex Jones’ Sandy Hook deposition,” (11:13 minutes). After showing the video, pose the following questions: (1) How will the families’ attorneys use this deposition to help make their case that Jones knowingly and intentionally promoted false information in reckless disregard of the truth? (2) Jones claims that some of his statements were the result of the media’s misreporting. Since news evolves quickly, and reporters don’t always have the

full picture when they file their stories, how important is the timeliness of corrections for defamation claims?

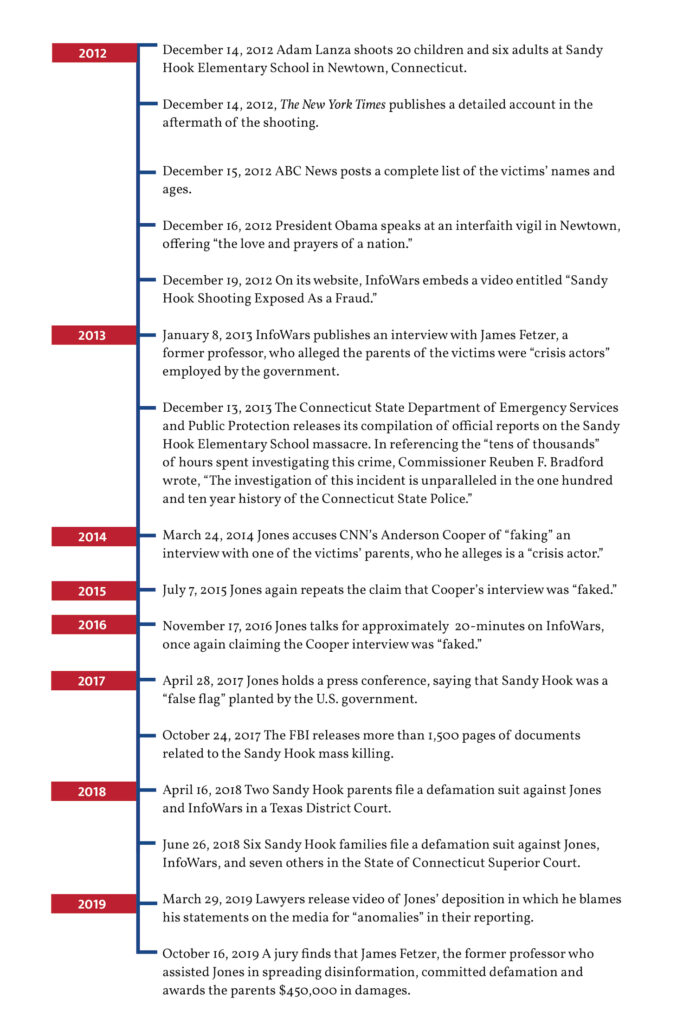

Table 1: In His Own Words

While this isn’t a comprehensive list of the events associated with the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings, nor a comprehensive list of all of Alex Jones’ statements, the timeline illustrates some of the evidence available to Jones before and after making his continued false statements about the massacre. Do the events bolster the plaintiffs’ allegations of intentional or reckless falsehood? Explain why or why not.

Lynn and Christopher McDonnell, the parents of seven-year-old Grace McDonnell, grieve near Sandy Hook Elementary after learning their daughter was one of 20 school children and six adults killed after a gunman opened fire inside the school in Newtown, Connecticut, U.S., December 14, 2012. Picture taken December 14, 2012. REUTERS/Adrees Latif/File Photo

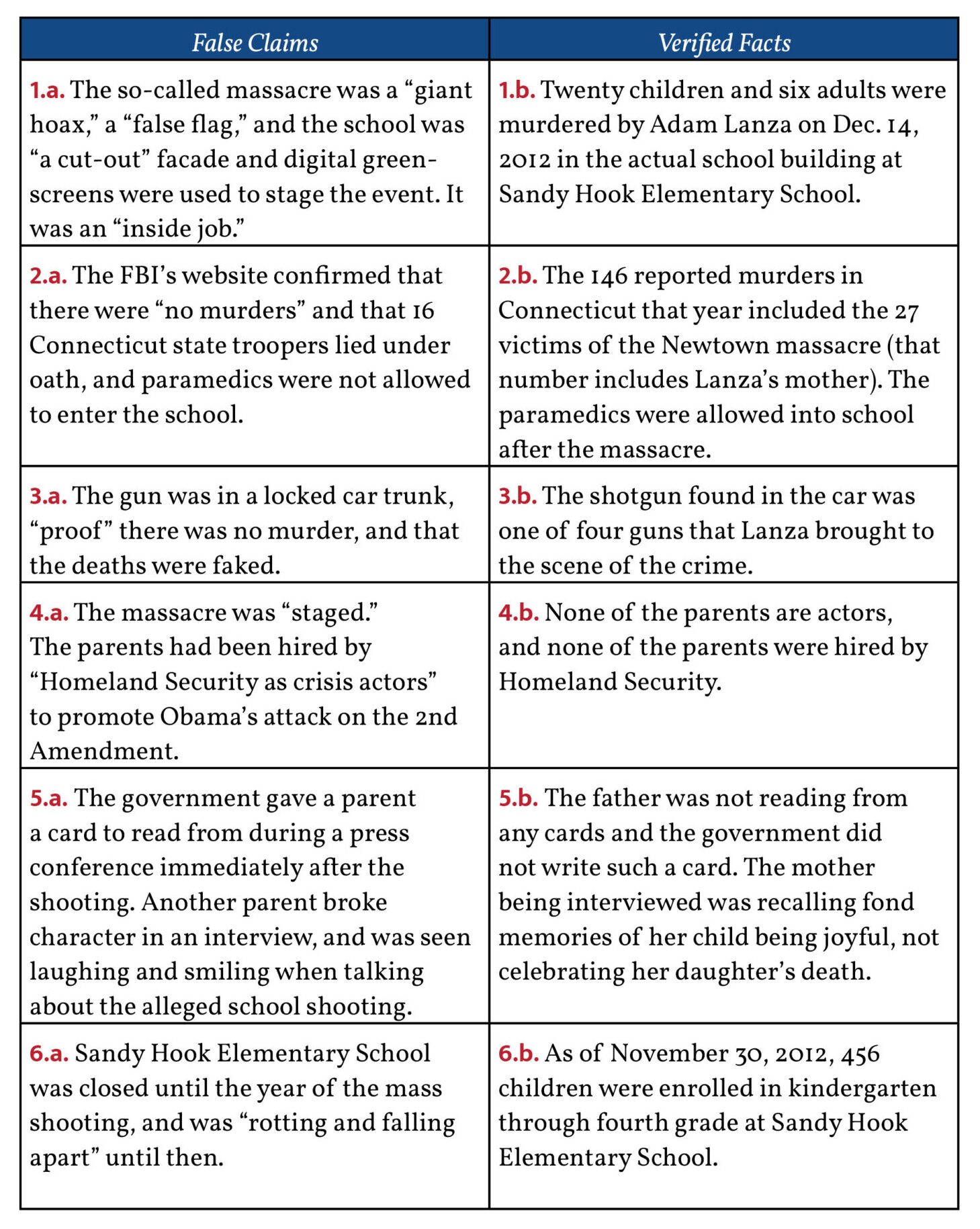

Table 2: Facts v. False Claims

Below are some of the claims Alex Jones made about events related to the Sandy Hook Elementary massacre. While this is not a comprehensive list of Jones’ statements, the ones listed are directly refuted by verified facts.

For links to false claims see pdf.

Issue 3: Is Opinion a Defense?

The First Amendment enables a libel defendant to use the defense of opinion. Libel pertains only to false statements of fact. An expression of opinion, on the other hand, typically involves subjective judgments and not factual statements. An opinion cannot be proven false.

As Justice Lewis Powell, Jr. wrote in the U.S. Supreme Court decision Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974), “there is no such thing as a false idea. However pernicious an opinion may seem, we depend for its correction not on the conscience of judges and juries, but on the competition of other ideas.”

But what exactly is opinion as distinguished from statements of fact? The U.S. Supreme Court in Milkovich v. Lorain Co. (1990) looked at whether a statement “is sufficiently factual to be susceptible of being proved true or false.” An opinion is inherently subjective and is not susceptible of being proved true or false.

A more detailed judicial test came with Ollman v. Evans (1984) in which a federal appeals court suggested a four-part test to determine whether a statement is protected opinion. The test brings context into the analysis, helping a court determine the difference between fact and opinion by examining how the article was presented to readers (news or op-ed, for example), and the contextual meaning of the words.

1. Is the statement verifiable, that is, capable of being proven true or false?

2. What is the common usage of the words in the statement?

3. What is the journalistic context in which the statement is made? (for example,

an op-ed would signal opinion); and

4. What is the social context in which the statement is made?

Apply the Opinion Standard to Alex Jones

“As a pundit, and as someone who is giving opinion, my opinions have been wrong but they were never wrong consciously to hurt people,” Jones said during a deposition. He also argued that opinions, even wrong ones expressed in the spirit of journalism, may have value under the First Amendment. In an attempt to dismiss a defamation lawsuit, Jones compared himself to Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, The Washington Post journalists who helped uncover the Watergate scandal. Jones said he was acting like a journalist when his opinion led him to question the narrative of the Sandy Hook school shooting in 2012. Lawyers for Jones wrote in his filing for dismissal: “Such journalism, questioning official narratives, would be chilled if reporters were subject to liability if they turned out to be wrong…. To stifle the press (by making them liable for merely interviewing people who have strange theories) will simply turn this human tragedy into a Constitutional one.” Jones acknowledged that some of his opinions were baseless, but asserted, “I was stating that I was reporting on the general questioning when others were questioning. And, you know, it’s painful that we have to question big public events. I think that’s an essential part of the First Amendment in America.”

In response, Bill Bloss, an attorney for the families, said in multiple news reports that, “The First Amendment simply does not protect false statements about the parents of one of the worst tragedies in our nation’s history. Any effort by any of the defendants to avoid responsibility for the harm that they have inflicted will be unsuccessful.”

Activity: Students as Judges

Invite students to reflect upon why the First Amendment protects expressions of opinion. Then invite students to imagine they are judges in a court. Have them apply the four-part opinion test to Alex Jones’ statements as detailed in Table 2. Invite students to determine (1) whether the statements were verifiable; (2) whether the statements express use common usage of words to convey their meaning; (3) the journalistic context in which Jones made his statements as signaling an assertion of fact or opinion; and (4) the social context in which his statements were expressed. Invite the students to analyze whether Alex Jones’ deposition statements about the Sandy Hook massacre constitutes opinion rather than meant as expressions of verifiable fact.

Issue #4: The Rhetorical Hyperbole

Another type of opinion defense involves rhetorical hyperbole. Again, defamation suits involve statements of fact. In some situations, an expression can be so outrageous or hyperbolic that no reasonable person would conclude that it constitutes a statement of verifiable fact.

For example, in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Greenbelt Cooperative Publishing v. Bresler (1970), a newspaper quoted a person who said that a developer’s negotiating position on a land deal with the city of Greenbelt, Maryland amounted to “blackmail.” The Court ruled that the statement in context did not actually accuse the developer of the crime of blackmail, but rather “even the most careless reader must have perceived that the word was no more than rhetorical hyperbole, a vigorous epithet used by those who considered [the developer’s] negotiating position extremely unreasonable.”

In another case, Supreme Court case, Letter Carriers v. Austin (1974), the use of the word “scab” for workers who crossed the picket line in a strike was “merely rhetorical hyperbole, a lusty and imaginative expression of the contempt felt by union members,” and not an accusation involving the crime of treason. Listeners and readers would understand it as a hyperbolic statement.

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court also ruled in Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) that an advertisement parodying Rev. Jerry Falwell, a public figure, as having “engaged in a drunken incestuous rendezvous with his mother in an outhouse,” was not reasonably believable as having been made as a statement of fact. Reasonable people would understand that it was rhetorical hyperbole, an exaggerated satirical comment on one of the most publicly religious and moral persons in the public square.

Discussion Questions

1. Why does the First Amendment protect hyperbolic expression? How common is hyperbole in political debate? What is the value of hyperbolic expression in political debate?

2. How would Alex Jones argue that his speech involving the Sandy Hook massacre constitutes rhetorical hyperbole? Does the quality of the statements, the quantity of them, and the fact that he repeated them over a four-year period matter when determining whether something is rhetorical hyperbole?

3. Do you think Alex Jones’ statements constitute rhetorical hyperbole—that is, would reasonable people hearing or reading his statements understand that he was making assertions of purported fact?

Resources

Multimedia

1. Watch: Christina Maxouris and Elizabeth Joseph, “Alex Jones says ‘form of psychosis’ made him believe events like the Sandy Hook massacre were staged.” CNN, April 1, 2019.

2. Watch: “Key moments from Alex Jones’s Sandy Hook deposition,” Washington Post, March 30, 2019. Full videos available at the Kaster Lynch Farrar & Ball LLP YouTube channel.

3. Watch: Holly Yan, “The father of a Sandy Hook victim dies from an apparent suicide.” CNN, March 25, 2019.

4. Listen: Michael Barbaro, “Listen to ‘The Daily’: Putting ‘Fake News’ on Trial.” New York Times, May 24, 2018.

5. Watch: “Sandy Hook parents sue InfoWars’ Alex Jones for defamation.” Reuters, April 18, 2018.

U.S. Supreme Court Defamation Cases

1. New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964). “A State cannot, under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, award damages to a public official for defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves ‘actual malice’––that the statement was made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of whether it was true or false.”

2. The two companion cases, Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 (1967) and Associated Press v. Walker, 388 U.S. 130 (1967), acknowledged that “the distinctions between government and private sectors are blurred” and, consequently, many private actors are “intimately involved in the resolution of important public questions.” The Court extended the proof of falsity and fault requirements to cases

in which public figures sued for defamation.

3. Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974). The decision created three categories of public persons: (1) the “all-purpose” public figure who holds “persuasive power and influence” or has such “pervasive fame or notoriety”; (2) the “voluntary, limited- purpose” public figure who asserts oneself into “the forefront of particular public controversy in order to influence the resolution of the issues involved; and (3) the “involuntary” public figure who, through no “purposeful action” of their own, is “drawn into a particular public controversy.”

4. Philadelphia Newspapers, Inc. v. Hepps, 475 U.S. 767 (1986). Requires private figures to prove falsity of any alleged defamatory statements.

5. Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co., 497 U.S. 1 (1990). Held that an “opinion privilege” does not apply to a statement that is objectively false.

Sandy Hook Defamation Cases

1. Jones v. Heslin, No. 03-18-00650-CV (Tex. App. Aug. 30, 2019). Travis County Judge Scott Jenkins granted a motion for sanctions and legal expenses against Jones and Infowars, ordering them to pay $65,825 for ignoring a court order about providing documents and witnesses. In another ruling issued that same day in Heslin’s case, Jenkins denied an Infowars motion to dismiss the case and ordered Jones and Infowars to pay an additional $34,323.80, for a combined total of $100,148.80 levied against Jones and Infowars in a single day. Added to an earlier October order against Infowars, Jones and his outlet have been ordered to pay $126,023.80 over the case, even before it reaches trial.”

2. Leonard Pozner v. James Fetzer, No. 18CV3122 (Dist. Ct. Wis., Dec. 12, 2019). James Fetzer, a retired professor who lives in the village of Oregon, Wisconsin, was found in June to have defamed the father of a victim of the Sandy Hook shooting in 2012. A jury awarded his victim, Leonard Pozner, $450,000 in damages after his attorneys argued Fetzer’s writing contributed to his post-traumatic stress disorder.

3. Erica Lafferty v. Alex Jones, Civil Action No. 3:18-CV-1156 (JCH) (D. Conn. Nov. 5, 2018). Case brought by six families was remanded to state court.) (For further study see plaintiff’s complaint and Jones’ failed motion to dismiss the complaint.)

4. Sherlach v. Jones, NO. 3:2018cv01269 (D. Conn.) Lawsuit against Alex Jones and Infowars and others by husband of Sandy Hook shooting victim William Sherlach, spouse of Mary Sherlach in Connecticut.) (Case remanded to state court. See case docket.)

In the News

Justine Coleman, “Lawyer seeks judgement without a trial for Alex Jones in Sandy Hook case.” The Hill, December 12, 2019.

Dave Altimari, “Connecticut Supreme Court agrees to hear appeal in lawsuit by Sandy Hook parents against InfoWars broadcaster Alex Jones.” Hartford Courant, July 10, 2019.

Susan Svrluga, “First, they lost their children. Then the conspiracy theories started. Now, the parents of Newtown are fighting back.” Washington Post, July 8, 2019.

David Owens, “Alex Jones appeals sanctions ruling in Sandy Hook parents’ lawsuit against him.” Hartford Courant, June 24, 2019.

Doha Madani, “InfoWars’ Alex Jones claims a ‘psychosis’ caused him to question Sandy Hook massacre.” NBC News, March 29, 2019.

Elizabeth Williamson, “Sandy Hook Families Gain in Defamation Suits Against Alex Jones.” New York Times, February 7, 2019.

Jacey Fortin, “Infowars Must Turn Over Internal Documents to Sandy Hook Families, Judge Rules.” New York Times, January 12, 2019.

Aaron Katersky, “Families of Sandy Hook shooting victims win legal victory in lawsuit against InfoWars, Alex Jones.” ABC News, January 11, 2019.

Dave Altimari, “Connecticut judge orders Alex Jones to turn over some Infowars financial documents to Sandy Hook families.” Hartford Courant, January 11, 2019.

Elizabeth Williamson, “Alex Jones of Infowars Destroyed Evidence Related to Sandy Hook Suits, Motion Says.” New York Times, August 17, 2018.

Brianna Sacks, “Alex Jones Is Trying To Get Out Of Court By Arguing That What He Says Is Not Real.” BuzzFeed, August 3, 2018.

Elizabeth Williamson, “In Alex Jones Lawsuit, Lawyers Spar Over an Online Broadcast on Sandy Hook.” New York Times, August 1, 2018.

Jon Herskovitz “Conspiracy theorist Jones seeks halt of Sandy Hook defamation suit.” Reuters, August 1, 2018.

“Alex Jones compares himself to Woodward, Bernstein in bid to dismiss Sandy Hook lawsuit.” CBS News, July 24, 2018.

Pat Eaton-Robb, “Infowars host Alex Jones moves to dismiss Sandy Hook lawsuit.” Associated Press, July 23, 2018.

Elizabeth Williamson, “Truth in a Post-Truth Era: Sandy Hook Families Sue Alex Jones, Conspiracy Theorist.” New York Times, May 23, 2018.

Brandy Zadrozny, “Six more families sue Alex Jones over Sandy Hook conspiracy claims.” NBC News, May 23, 2018.

Robert Storace, “Connecticut Lawyers Sue Conspiracy Theorist Alex Jones for Sandy Hook Families, FBI Agent.” Connecticut Law Tribune, May 23, 2018.

Matthew Haag, “Sandy Hook Parents Sue Alex Jones for Defamation.” New York Times, April 17, 2018.

For Further Study

Michale Ray, “Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.” Encyclopedia Britannica, December 7, 2019.

“Sandy Hook shootings: Four things revealed by FBI files.” BBC News, October 25, 2017.

David L. Hudson, Jr., “Defamation.” The First Amendment Encyclopedia.

Glossary

Actual Malice is the fault standard that public officials and public figures must meet to win a defamation case. It requires clear and convincing evidence that the defamatory statement was published with knowledge of falsity or with reckless disregard for whether it was true or false.

Clear and convincing evidence is the standard of proof used when public officials and public figures sue for defamation. It is more onerous than the preponderance of the evidence standard (more likely than not) but less rigorous than the criminal law standard – “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Defamation is the use of false and malicious expression to injure a person’s reputation. This includes either written (libel) or verbal (slander) expression. See New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964); Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323 (1974);

Disinformation is an expressed misrepresentation of facts. Similar to propaganda, misinformation can be targeted toward a particular audience with the intent to influence their thinking on a particular issue.

Libel is written defamation of a person’s reputation or character as a result of a published false statement.

Slander is a verbal form of defamation when speaking malicious and false words regarding another’s character or reputation.

Rhetorical Hyperbole is a form of protected speech under the First Amendment. See Watts v. United States, 394 U.S. 705 (1969); Letter Carriers v. Austin, 418 U.S. 264 (1974); and Clifford v. Trump, 339 F. Supp. 3d 915 (2018).

Tags