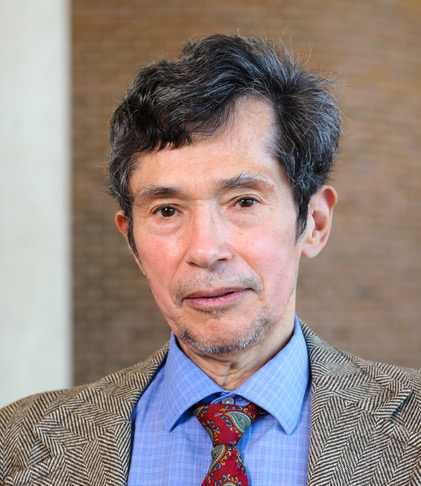

Professor Richard Delgado received his A.B. from the University of Washington and his J.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, where he was Notes and Comments Editor for the California Law Review. Before coming to Alabama in 2013, he taught at the University of Pittsburgh, Colorado, and UCLA.

Author of over one hundred journal articles and twenty books, Delgado’s work has been praised or reviewed in The Nation, The New Republic, the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal. His books have won eight national book prizes, including six Gustavus Myers awards for outstanding book on human rights in North America, the American Library Association’s Outstanding Academic Book, and a Pulitzer Prize nomination. Professor Delgado’s teaching and writing focus on race, the legal profession, and social change.

Free Speech – Progressive or the Opposite?

Of course free speech can be progressive, promote racial equality, human flourishing, and communities that understand and respect each other. But it can also be regressive, as with hate speech, bullying, and spreading malicious rumors on social media. In Rwanda it contributed to genocide. In Charlottesville, it enabled Nazis and white supremacists to parade in a peaceful college town, terrifying the residents and sowing confusion and even death.

Almost any constitutional value, such as the freedom to own guns, can be used for good or for ill. Free speech is no different.

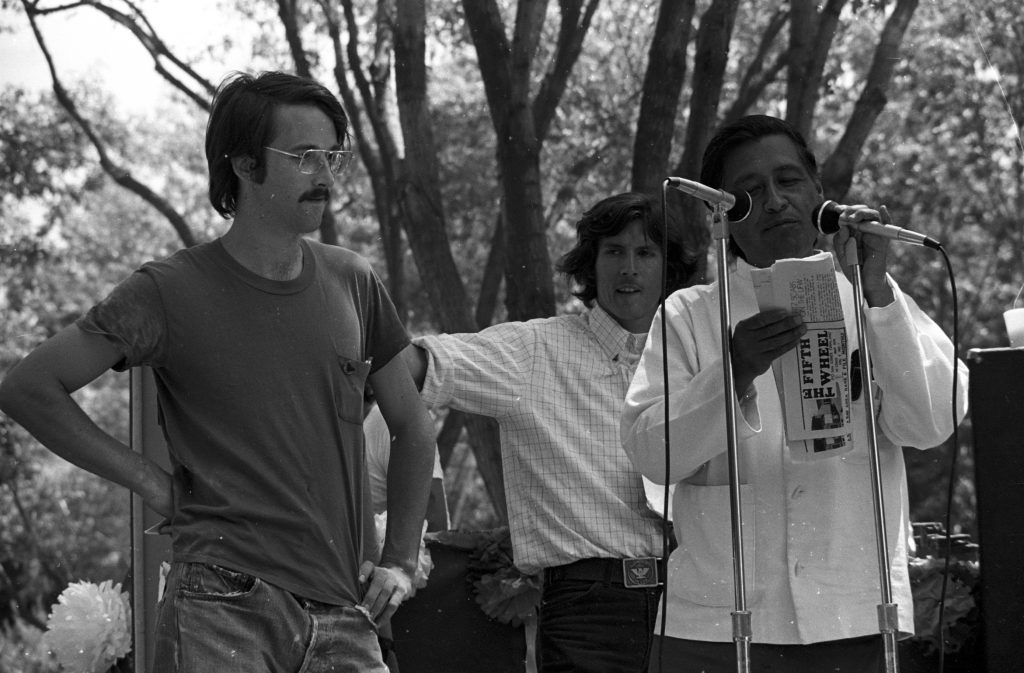

Activist Cesar Chavez speaking at a 1974 United Farm Workers rally in Delano, California.

A point of confusion

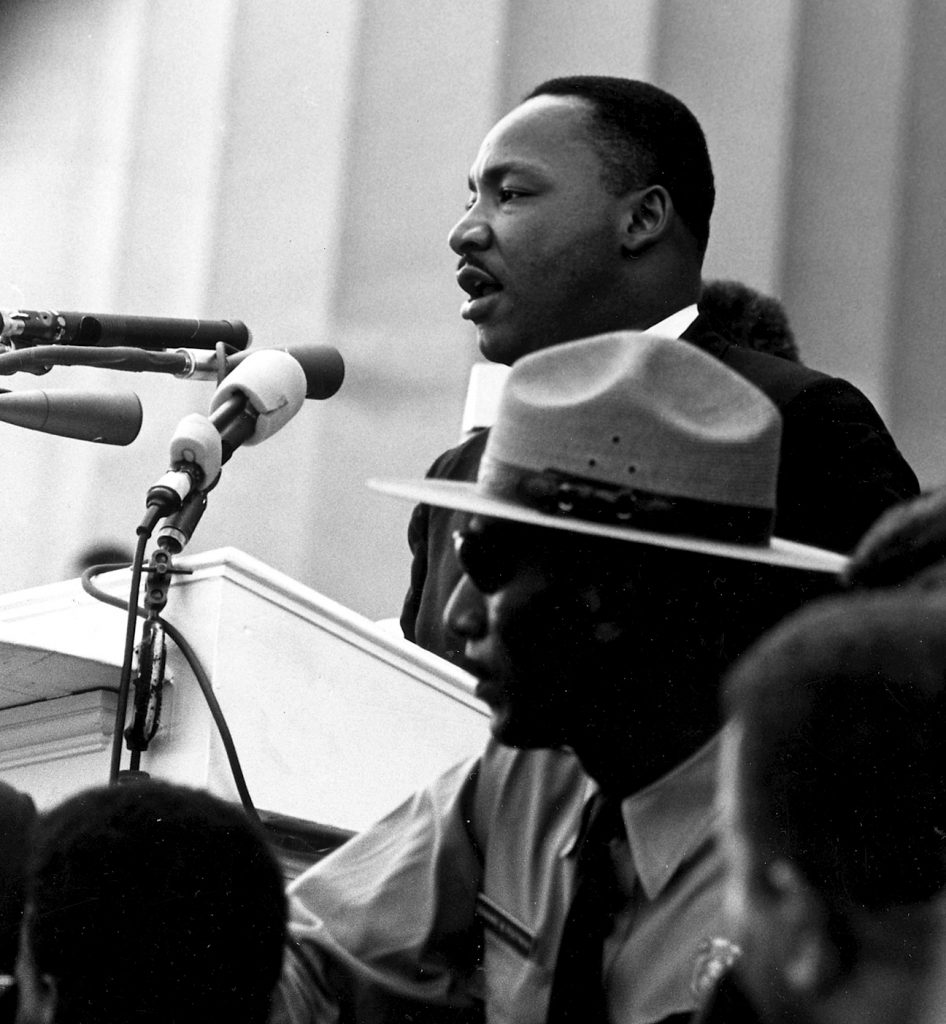

Free speech absolutists get a lot of mileage out of pointing out that free speech was valuable for racial minorities like me, and that we, of all people, should realize that much of our own progress was due to abolitionist speech and Martin Luther’s “I Have a Dream” address that moved millions. But this rests on a confusion.

Courageous advocacy and speech may have been essential to minority progress. But the system of free speech played little part in it. As often as not, speakers like Cesar Chavez or Martin Luther King spoke out against the day — picketed, sat in, spoke, leafleted — and went to jail. Free speech law did not protect them. Their speech had too much “muscle,” or took place in the wrong forum or without a permit. Years later, at considerable cost and as a result of much courageous lawyering, a higher court may have reversed their conviction.

But free-speech law, as then understood, did them little good. It’s easy to forget that laws, included the ones laid down by the Framers, represent the interests of the empowered group that enacts them. The First Amendment is no different.

Formalistic reasoning & the absence of legal realism

So, Professor Seidman is right, for this reason among others. But progress via the First Amendment’s free-speech clause is halting and slow for a second reason. First Amendment jurisprudence is one of the most formalistic areas of judicial reasoning. It is redolent of wooden categories (speech/action; no content regulation), maxims (“the best cure to bad speech is more speech”), thought-ending clichés (the First Amendment as seamless web), exhortations that ring hollow to one-half the population (“if minorities only knew their own self-interest, they would never limit speech”), and dozens of “tests” and special doctrines. (See Richard Delgado, Review: Toward a Legal Realist View of the First Amendment, Harvard Law Review (2000); First Amendment Formalism is Giving Way to First Amendment Legal Realism, Harvard Civil Rights & Civil Liberties Law Review (1994).

Martin Luther King gave his most famous speech, “I Have a Dream”, before the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Unlike other areas of law that have greatly benefited from the realist revolution of the last century, First Amendment doctrine proceeds as though the realists and critics had never existed. No wonder it resists balancing, sociological jurisprudence, perspective-changing, and any of the other tools of critical thought that have enabled progress in dozens of other areas, including family law, torts, consumer protection, and environmental protection.

Liberty vs Equality: Resolving the conflict

How to make sense of this conflict? I offer the following: Free speech and equality interests often come into conflict, as they do with hate speech, campus climate controversies, and sexual harassment in the workplace. When they do, we should resolve the controversy in light of what’s at stake and the stage society is undergoing at the time. Free speech values promote social change and ferment. They are most valuable when society is stuck (the 50’s) and needs to break out of a rut (the 60’s). Then, it needs new voices, proposals, literature, experimentation, and suggestions

At other times, however, society is in turmoil. Minorities are under threat. Immigrants are castigated. Gays, despised. At times like these, society needs protection. It needs stability. Oppressed people need safety and the opportunity to consolidate gains. Then, the equal-protection values emanating from the equality amendments (the thirteenth and fourteenth) should preponderate, and free speech take second place for a while. As a look at any day’s headlines will tell you, we are at one such stage now.

In short, CLS (Critical Legal Studies) 101.