President-elect Donald Trump returns to the Oval Office on Jan. 20, and press freedom experts have raised concerns over how journalists might be targeted in the next four years.

National newspapers have increased their use of encrypted communications to protect themselves from possible leak investigations under a second Trump administration, and media organizations have begun evaluating their insurance to ensure they can “absorb a potential wave of libel and other litigation from officials,” according to The New York Times.

Trump has filed lawsuits against The New York Times, CNN, CBS, The Washington Post, ABC News and the Des Moines Register. These suits have been described by legal scholars as strategic lawsuits against public participation, or SLAPP suits, which are often used in an attempt to stifle speech by imposing steep legal fees and threats of lengthy litigation. Thirty-four states and the District of Columbia have varying degrees of anti-SLAPP legislation on the books.

The most powerful protections for the press, though, come not from statutes but from the First Amendment — and most notably from the 1964 landmark case, New York Times v. Sullivan.

In 1964, the Supreme Court in Sullivan held that public officials and public figures can’t prevail in a defamation suit without proving what it called “actual malice”— that a statement was false and that, in addition, it was made “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

The courts have defined reckless disregard as proof that the defendant entertained serious doubts as to the truth or had a high degree of awareness of probable falsehood, and published anyway.

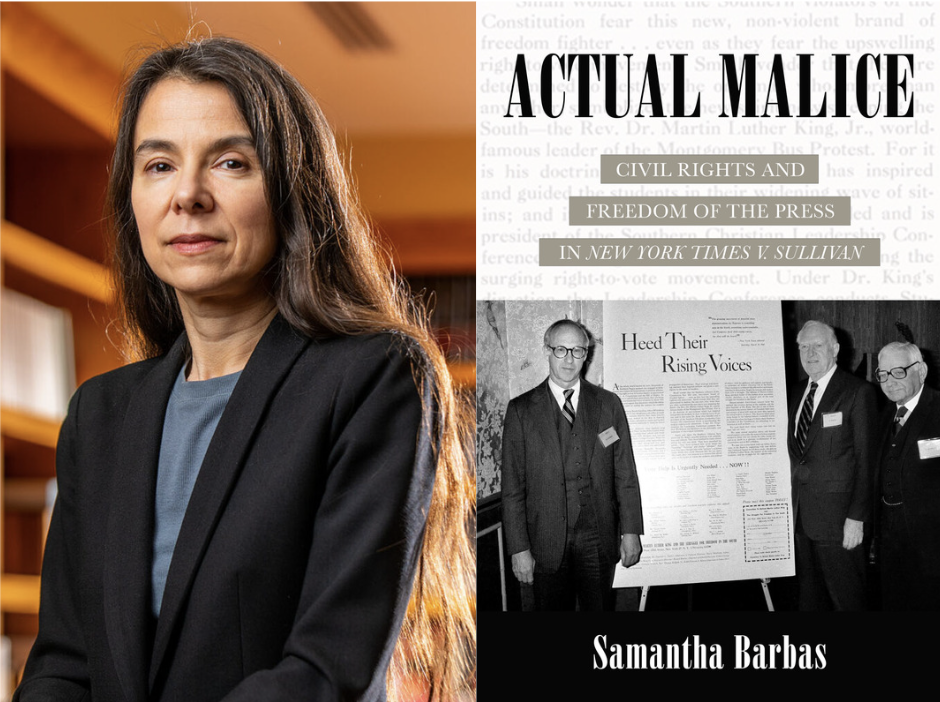

Samantha Barbas is a professor of law at the University of Iowa College of Law who has frequently commented on press freedom and civil protections offered to journalists. She has authored several books on mass media law and history, including “The Rise and Fall of Morris Ernst: Free Speech Renegade” published in 2021 and “Actual Malice: Civil Rights and Freedom of the Press in New York Times v. Sullivan” published in 2023.

In an interview with First Amendment Watch, Barbas shared her expectations for a second Trump presidency regarding press freedom, explained reasons why the press could cover the administration differently, and predicted that conversations surrounding the reconsideration of Sullivan will continue under Trump.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

FAW: What are your expectations for press freedom and libel law during Trump’s second administration?

Barbas: There are a couple of important things to consider. First of all, it’s very clear that Trump and his allies are using libel lawsuits as a way to punish, intimidate and silence the press, and we’ve seen so many high value lawsuits being brought against outlets like CNN, the Washington Post, The New York Times by Trump himself. Of course, none of those have succeeded until recently, when we had the ABC lawsuit, which settled for $15 million, and I’m sure Trump and his allies saw that as a tremendous victory, which no doubt will embolden them to bring more of these abusive and threatening libel lawsuits.

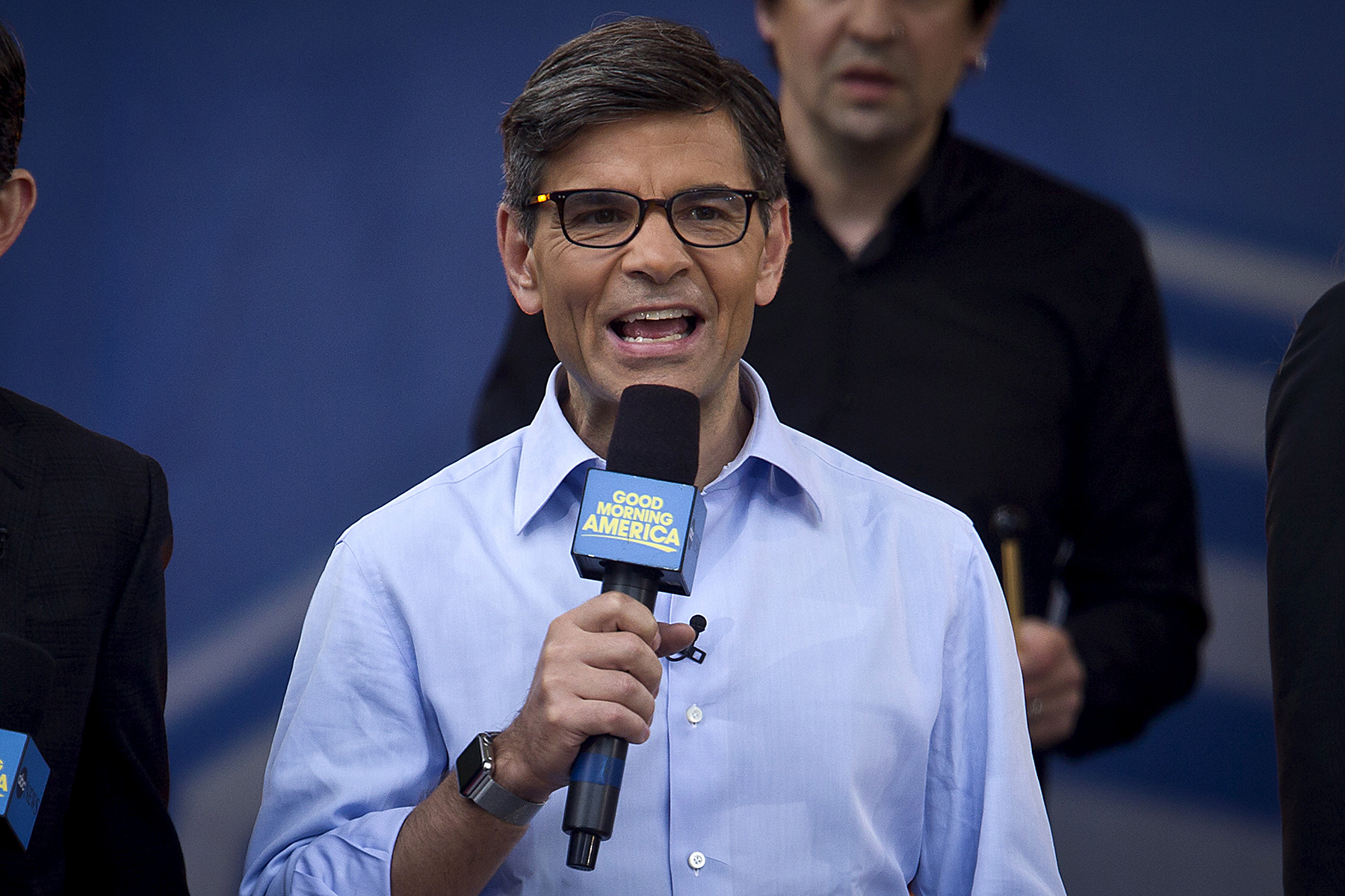

FAW: In December, ABC agreed to pay $15 million toward Trump’s presidential library and $1 million in legal fees to settle a defamation lawsuit he filed against anchor George Stephanopoulos for stating on-air that Trump was held civilly liable for “rape” in the E. Jean Carroll trial when he was found legally liable for “sexual abuse.” Given that the federal judge who oversaw both trials wrote that Trump did “rape” Carroll “as that term commonly is used and understood,” do you think Trump could have proven a reckless or intentional falsehood?

Barbas: Well, it’s difficult because we don’t have all of the information. Because the case didn’t go forward, we don’t know what I suppose that Stephanopoulos actually knew, when he made that statement. As to the question of whether or not it was false that Trump raped E. Jean Carroll, I guess that’s kind of the issue. But their argument was that, well, there was a fine distinction between, I suppose, sexual assault and rape, and that it might not be technically true under legal definitions to say that you raped her. And if you really want to get that precise about it, well, possibly there is a distinction in meaning, although, again, now it’s been very technical.

FAW: Where do you think ABC might have been vulnerable had the lawsuit proceeded? Does ABC’s decision affect how other media organizations might cover the administration?

Barbas: Definitely. Again, we don’t know the state of mind of the speakers at the time, which is critical in determining actual malice. Possibly one consideration of ABC in settling might have been that it would have to go before a jury that was hostile towards the press. It was in Florida, I believe, not necessarily the most friendly constituency towards the media, and probably very favorable to Trump. So what this would indicate for the media going forward is, yes, they will be likely more prone to self-censor, because they don’t want to face these major lawsuits and potentially jury trials in hostile jurisdictions that could be very damaging.

FAW: Are there any protections against this kind of forum shopping, that is, filing the lawsuit in a jurisdiction where people hold hostile feelings toward the press? And can media organizations rely on appeals courts to overturn these jury verdicts if they materialize?

Barbas: There are protections against forum shopping, but in this case, Trump sued in his home state. Media organizations often do successfully appeal in libel cases, but success is not guaranteed. It is, however, probably easier to get a jury verdict overturned in a defamation case than most other kinds of lawsuits.

FAW: Does a settlement like ABC’s encourage the filing of more defamation suits in the future?

Barbas: Definitely. [On Dec. 16], after the settlement was announced, Trump had a press conference where he said that he was going to bring more defamation suits against the media because the press needed to be “straightened out.” And then he proceeded to file this lawsuit against the Des Moines Register because they printed a poll that ultimately turned out to be inaccurate, and he’s using some really far-fetched consumer fraud law to say that the newspaper perpetrated a fraud on the public when it published a poll that wasn’t completely accurate. So I think this is just the beginning of these very far-fetched and harassing lawsuits against the press.

FAW: What do you think will likely be the outcome of this lawsuit? Do you see a good strategy for responding to these harassing lawsuits? Are sanctions possible against lawyers who repeatedly file such cases?

Barbas: The lawsuit will be dismissed. The best strategy in these cases would be to have the lawsuits dismissed. Media lawyers could also attempt to invoke anti-SLAPP laws, depending on the state. Under an anti-SLAPP law, a plaintiff bringing a frivolous lawsuit designed to chill free speech may have to pay attorneys’ fees and court costs.

FAW: In January 2017, Trump stated that “our current libel laws are a sham and a disgrace and do not represent American values or American fairness.” This alluded to the Supreme Court reconsidering New York Times v. Sullivan — the landmark 1964 case that established the actual malice standard. Trump also said he’d “open up” libel laws to make it easier for public officials like himself to sue the press for defamation. Is this possible?

Barbas: What Trump has done since he began making those statements back in 2016 was that he’s kind of rallied the troops and gotten a lot of conservative lawyers and activists behind this anti-New York Times v. Sullivan stance, and that has meant the publication of a lot of articles and op-eds, but also, more threateningly, attempts to queue up a test case that would get to the Supreme Court and would give it an opportunity to reconsider Sullivan and some of the related extension cases that applied Sullivan to public figures. So I think that that movement is going to continue, and whether or not it actually results in a Supreme Court ruling, that’s a more difficult question. But to me, there’s no question that this flood of lawsuits is going to continue.

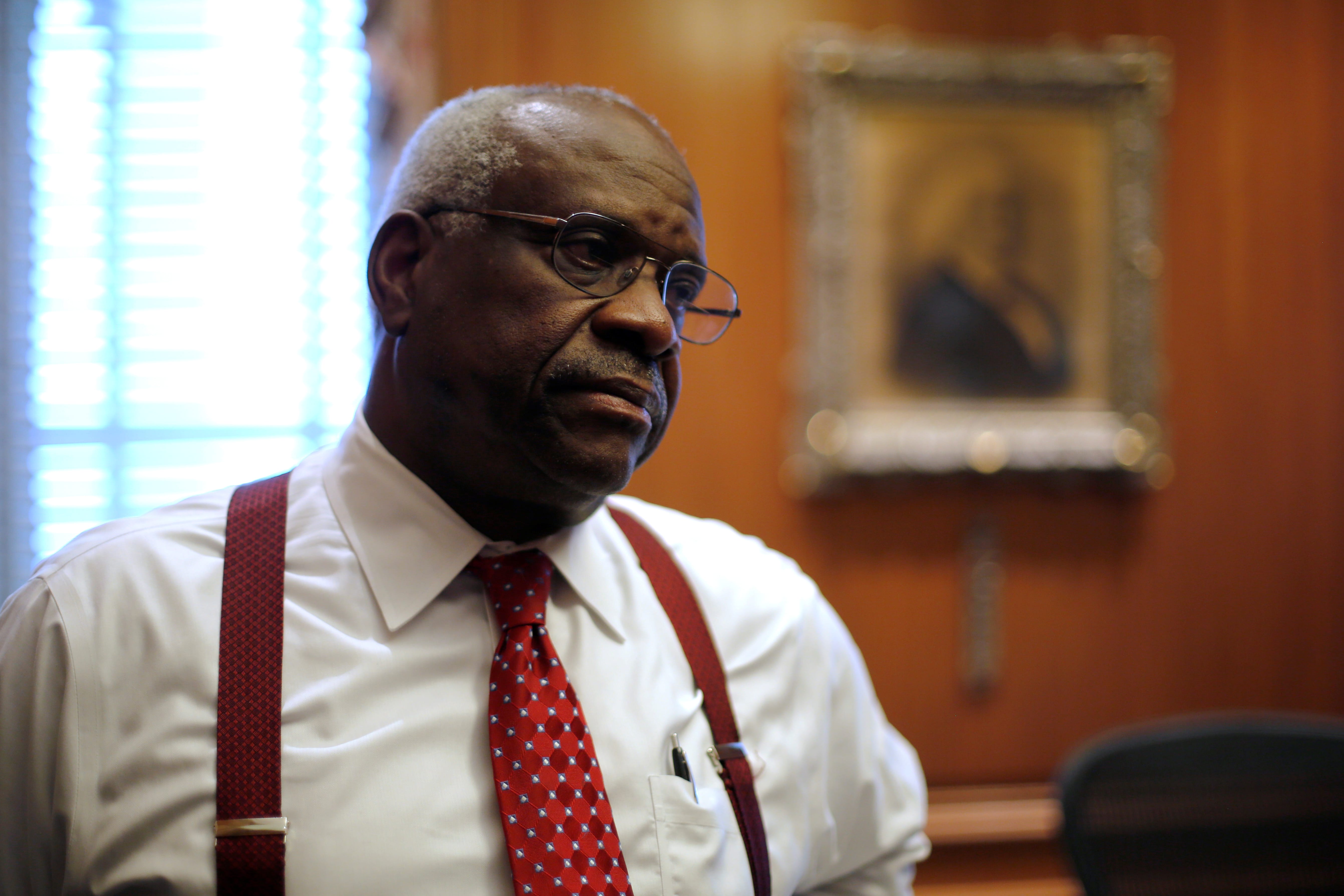

FAW: Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch have been outspoken about reconsidering Sullivan. What would need to happen for a reconsideration of Sullivan to actually occur? What do Thomas and Gorsuch hope to change? Are there any changes that could be made to Sullivan that wouldn’t be harmful to the media?

Barbas: Thomas has said on a number of occasions that he would vote to overrule New York Times v. Sullivan itself, and presumably all the related cases. And the reason for that, he says, is that New York Times v. Sullivan, actual malice has no basis in the Constitution. So according to his originalist reading of the First Amendment, Sullivan is unconstitutional. He’s the only justice that has that extreme position. Gorsuch, as you mentioned, has suggested that he would like to reconsider a few cases that were decided after Sullivan that dealt with public figures bringing libel suits. So Sullivan dealt only with public officials. If those public figure cases were to be modified, it would have a tremendous effect on the press, because according to the Supreme Court’s definition of a public figure, many individuals are public figures. You can be a public figure just by speaking out on a public issue or writing about something on social media. So if that precedent were to be changed, that really would have an effect on media behavior. But Gorsuch is the only one who has really talked about the public figure rulings.

FAW: The Supreme Court in recent years has often reasoned using its analysis of the original understanding of the Constitution. Let’s say the actual malice test is challenged in a case before the justices. How do you think original understanding of the freedom of speech and press clauses would support the actual malice test that requires plaintiffs to prove a reckless or intentional falsehood?

Barbas: There’s been a lot of debate recently in academia about whether or not actual malice is or is not consistent with the original meaning of the First Amendment. And I think you could argue that indeed, the framers did have in mind broad protections for speakers who criticize public officials. Really, that’s an essential part of democracy, is the ability of citizens to monitor the people who govern them by commenting on them. So it’s not certain that an originalist argument would lead to overruling New York Times v. Sullivan.

FAW: What are some key writings or debates of the founding period that support the Sullivan protections for the press? Does the debate over the Sedition Act of 1798 provide any support for this broad protection for the press?

Barbas: There has always been significant debate as to whether the framers intended for the First Amendment to protect speakers from libel suits when criticizing public officials. Herbert Wechsler, the attorney for the Times in the Sullivan case, argued that the debate over the Sedition Act of 1798 (which criminalized criticism of government) illustrated that the framers intended free speech protections in libel law. James Madison and other framers argued that the Sedition Act impaired the “central meaning” of the First Amendment, which is the right of citizens to criticize government freely. Strict libel laws, Wechsler reasoned, would impair the spirit and purpose of the First Amendment.

FAW: After years of litigation, do you think the definition of public figures for the purpose of defamation law is precise enough?

Barbas: There’s been a lot of discussion as to whether or not that standard is too broad. Currently, the court’s language is, if you put yourself into the vortex of a public issue or controversy, you’re a public figure. And again, it can be taking a very minor step, like publicly protesting on the National Mall or writing about something on your blog. And the criticism of that is that people lose protection for their reputations, just by participating in public life, and that could potentially deter people from being involved in public issues. So that’s a criticism. On the other hand, that standard does allow the media a lot of freedom to report on people and on public issues without worrying about potentially devastating libel judgments. So I think if any change is made to the public figure doctrine, it would be narrowing the definition of who is a public figure. So maybe saying that you’re only a public figure if you consistently put yourself in the public eye, like if you’re a celebrity or a pundit, someone who’s making a living out of being in public. But it shouldn’t apply to just the average citizen who’s blogging or making some other minor comment.

FAW: Does the rise of social media change our thinking of who is a public figure for purposes of defamation? How would you define a public figure in the context of someone commenting on an issue on a social media platform?

Barbas: Yeah. And I think that was part of Gorsuch’s criticism, like with the rise of social media, literally we’re all public figures if we participate at all in this type of speech, and that that is simply unfair to people who deserve to have some legal protection for their reputations. So again, one prominent argument in the attempt to overrule Sullivan and the other cases is that, well, social media has basically changed the terrain, and because of this, we need to radically rethink the balance between freedom of speech and protection for reputation.

FAW: As one of the leading experts, how do you think some of these big legal questions can be resolved? If you were sitting on the court with Justice Gorsuch, what position would you be taking?

Barbas: I think it’s important to consider how the social environment, and the workings of the media industry, have changed since 1964, and to think about how this new social landscape may affect people’s ability to protect their reputations. Even though social media may have created a climate where reputations are more vulnerable to criticism and attack, it’s nonetheless essential to protect freedom of speech and press, and people’s ability to speak out on public issues. I’d argue that New York Times v. Sullivan is more important than ever, given how politicized libel law has become in recent years. There are more people today who are hostile towards the press, who would love to use libel lawsuits to sue the press out of existence, as we’ve seen with the recent resurgence of libel suits. Without the protections of Sullivan, the destruction of the press through libel lawsuits could become a possibility.

More on First Amendment Watch: