The First Amendment Bubble , “In determining the news that’s fit to print, U.S. courts have traditionally declined to second-guess professional journalists. But in an age when news, entertainment, and new media outlets are constantly pushing the envelope of acceptable content, the consensus over press freedoms is eroding. The First Amendment Bubble examines how unbridled media are endangering the constitutional privileges journalists gained in the past century.” – Harvard University Press.

Amy Gajda is the Class of 1973 Professor of Law at Tulane University Law School and a former journalist whose work navigates the tensions between privacy rights and protected expression. Her work examining First Amendment limits on judicial oversight of the press and academia appears in leading law reviews and she has presented her work in Australia, China, England, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, and throughout the United States. Her two books—The First Amendment Bubble: How Privacy and Paparazzi Threaten a Free Press and The Trials of Academe: The New Era of Campus Litigation—were published by Harvard University Press.

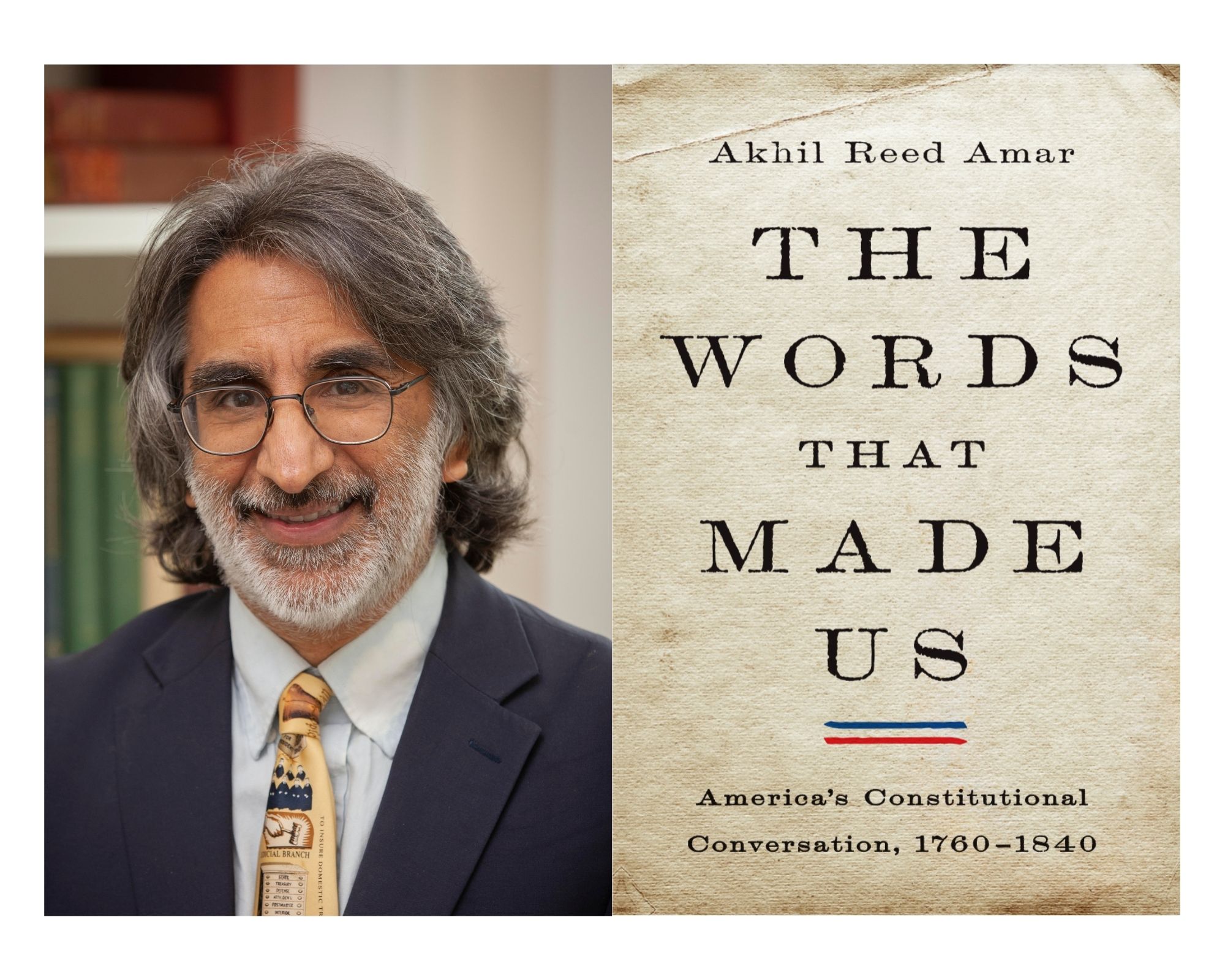

Authors Share Excerpts on Free Speech:

Amy Gajda and The First Amendment Bubble

Excerpted from The First Amendment Bubble: How Privacy and Paparazzi Threaten A Free Press by Amy Gajda, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2015 by The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Adaptation of 1,900 words from Chapter Two, “Legal Protections for News and Truthful Information: The Past” pages 24‐26 and 46‐49

The cover of the June 1940 edition of Headquarters Detective: True Cases from the Police Blotter magazine features a pale young woman bound to a chair. Her eyes are wide and her mouth is open as if terrified at what she sees off-cover. One of the straps of her tight, flimsy nightgown has fallen down her arm, making it seem as though her left breast will soon be exposed. The cover is mostly black and white, save for two red-highlighted articles: “Trailing the Tourist Camp Killers!” and “Slave to a Love Cult.” Articles inside are headlined “Murder in the AIR!,” the story of what is alleged to be the first killing onboard an airplane, and “GIRLS’ REFORMATORY,” an exposé that reveals that even those girls who “came in there decent” left with “all the vices of the underworld.” Many photographs inside the magazine feature scantily clad women-in-trouble but the most striking are those of the dead bodies of real-life crime victims, some in shockingly close-up detail.

Headquarters Detective was clearly one of the very first push-the-envelope publications, the precursor to today’s reality crime efforts such as the television programs Cops and The First 48 and the coverage one might find in tabloids like the New York Post. It is doubtful, however, that even the most strident of mainstream television programs, magazines, or newspapers today would publish the random bloodied dead body photos that appear to be a key part of Headquarters Detective magazine.

Headquarters Detective was clearly one of the very first push-the-envelope publications, the precursor to today’s reality crime efforts such as the television programs Cops and The First 48 and the coverage one might find in tabloids like the New York Post. It is doubtful, however, that even the most strident of mainstream television programs, magazines, or newspapers today would publish the random bloodied dead body photos that appear to be a key part of Headquarters Detective magazine.

And yet, as the Supreme Court would decide in 1948, such sensationalism in news is perfectly fine in a constitutional sense.

That particular copy of Headquarters Detective had reached the Supreme Court after a bookseller in New York was convicted of a misdemeanor for selling it. Such a sale violated a New York statute that prohibited sales of any publication “principally made up of criminal news, police reports, or accounts of criminal deeds, or pictures, or stories of bloodshed, lust, or crime.” The June 1940 edition of the magazine was clearly that. A New York appeals court accurately described it as “a collection of stories that portray in vivid fashion tales of vice, murder, and intrigue . . . embellished with pictures of fiendish and gruesome crimes . . . besprinkled with lurid photographs of victims and perpetrators.”

Though based on real-life crimes and related tales, the publication and sales of such magazines, a lower appellate court had decided, “tend to demoralize the minds of their more impressionable readers.” For the betterment of society, its “general welfare” and “morals,” the lower court held that the law forbidding sales of Headquarters Detective and its ilk was a perfectly constitutional use of the state’s police power. To that court, freedom of the press was trumped by the state’s interest in protecting its citizens from such mind-numbing licentiousness.

New York’s highest court agreed. Such magazines, filled with real-life “details of heinous wrongdoing,” appealed to a certain segment of the public that needed guidance, the court decided, and the statute merely served to maintain public order and stop the corruption of their and others’ public morals. The First Amendment, for its part, in the court’s mind, did not protect the truthful lewdness that was Headquarters Detective.

Justice Stanley Reed

With three strikes against it, the issue of the magazine featuring the bound woman with her mouth agape made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Justices, however, saw things differently: they struck down the statute that had criminalized it. In doing so, they both questioned and celebrated the Headquarters Detective family of publications. “Though we can see nothing of any possible value to society in these magazines,” the Justices in the majority wrote, “they are as much entitled to the protection of free speech as the best of literature.” Over the dissenting opinion of three Justices who argued that statutory prohibitions against mischief-making publications help solve societal problems, a majority of the Court decided that statutes like the one in New York were unconstitutional and that courts could not, in a constitutional sense, decide for all of society what is appropriate reading and what is not.

[READ MORE ON: Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948)]That decision from 1948 was one of the first indications that modern courts would look more favorably on truthful publications that push the envelope, even over arguments that public minds, public morals, and good taste were at stake. It marked what might be called a shift in the law, as up to that point, courts had more often condemned media for its immorality and bad influence. Now, even publications that arguably did not move society forward in any way and, in fact, reveled in its brutality, deserved the same level of protection as highbrow publications.

. . .

Bartnicki’s Shift

There is no precise moment at which the tables began to turn for media, of course. And clearly, given such strong pro-press history and language, many courts continue to decide cases in the media’s favor. It seems, however, that the turn of the century—perhaps not coincidentally also the time in which the Internet became significant—is when courts more routinely began to second-guess news judgment and when many began to drop the use of language that was excessively deferential to media.

The U.S. Supreme Court expressed its own concerns during that period in a roundabout way in Bartnicki v. Vopper. The case was a win for media, but hinted of a significant forthcoming loss.

[READ MORE ON: Bartnicki v. Vopper, 532 U.S. 514 (2001)]The Bartnicki facts were slightly different from those in which journalists had reported information gleaned from a police source: a news-talk radio station in Pennsylvania had played a tape of a cellular telephone conversation that had been recorded surreptitiously. The tape of the phone call had been placed anonymously in a local citizens group leader’s mailbox and was then passed on to the radio station. The recorded call, between the chief negotiator for a teacher’s union and the president of that union, suggested that violence might be appropriate should negotiations break down. The president was said to have said:

If they’re not going to move for three percent, we’re gonna have to go to their, their homes . . . To blow off their front porches, we’ll have to do some work on some of those guys. Really, uh, really and truthfully, because this is, you know, this is bad news. . . .

After the radio station aired the conversation, the union negotiator and union president sued it and others for statutory violations related to wire-tapping. The radio station defended on First Amendment grounds, arguing that the news value of the tape in which a union leader seemed to threaten violence trumped whatever privacy concerns existed in the conversation itself. When the case reached the Supreme Court, the Justices put the issue this way: “[W]hat degree of protection, if any, [does] the First Amendment provide[] to speech that discloses the contents of an illegally intercepted communication?” It explained that the conflict was one between interests of the highest order: the value of public information versus the value of individual privacy.

Justice John Paul Stevens

In the end, the news media and the value of public information won out. Six of the Justices joined a majority opinion stating that they were “firmly convinced” that the radio station that played the tape was protected in doing so by the First Amendment, given the news value of the conversation. “In this case,” the Justices wrote, “privacy concerns give way when balanced against the interest in publishing matters of public importance.” They explained that the surreptitiously recorded conversation involved a matter of unquestionable public concern—the months-long negotiation over a teachers’ contract—and therefore trumped any privacy for those whose conversation had been recorded. The Justices noted in particular that the broadcasters themselves had not done anything unlawful and stressed that their lack of involvement in the underlying illegal activity was key to finding that their behavior in airing the tape was protected constitutionally.

The three dissenting Justices, however, valued privacy more strongly than the news value within the taped conversation and voted against the media defendants. “Surely ‘the interest in individual privacy’ at its narrowest must embrace the right to be free from surreptitious eavesdropping on, and involuntary broadcast of, our cellular telephone conversations,” the dissenters wrote, noting that those involved in the conversation had only intended to have a private telephone conversation and had not intended to contribute to a public debate about anything.

What makes Bartnicki such a close decision despite its six-three outcome, however, is that two of the Justices who signed onto the majority opinion wrote a separate concurring opinion that warned that an end to expansive media freedoms in the area of news judgment was on the horizon. “[T]he Court’s holding does not imply a significantly broader constitutional immunity for the media,” the Justices explained, restating that the Bartnicki decision was a narrow one and suggesting that in a situation involving the publication of “truly private matters,” the Court would have decided it differently. The two Justices then wrote that new encroachments upon privacy had created a need for strong pro-privacy legislation, harkening back to Warren and Brandeis’ sensibilities in [their famous law review article] “The Right to Privacy”:

Clandestine and pervasive invasions of privacy . . . are genuine possibilities as a result of continuously advancing technologies. Eavesdropping on ordinary cellular phone conversations in the street (which many callers seem to tolerate) is a very different matter from eavesdropping on encrypted cellular phone conversations or those carried on in the bedroom. But the technologies that allow the former may come to permit the latter.

“Legislatures,” the Justices explicitly advised, may therefore draft “better tailored provisions designed to encourage, for example, more effective privacy-protecting techniques” without constitutional worry because the interests in protecting “basic personal privacy” were so strong.

It is possible, then, to read Bartnicki as a five-to-four decision against media, one in which five Justices, a majority, ruled that personal privacy did, in fact, trump newsworthiness at certain times—just not under these unique facts of a teachers’ contract and threats of potential violence.

Hulk Hogan

Moreover, and as if foreseeing the Hulk Hogan sex tape scenario[in which the Gawker website published a sex tape featuring the professional wrestler, ultimately leading to a jury verdict and resulting in a $31 million dollar settlement in favor of Hulk Hogan], the two concurring Justices suggested that even public figures had the right to private communication and private matters, explaining that, to them, a sex tape featuring a “famous actress and a rock star” would not be a matter of legitimate public concern. Of great relevance to Hulk Hogan’s plight, if three justices would have found a privacy violation in the broadcast of a surreptitiously recorded phone call regarding union activities, they certainly would have found a privacy violation in a surreptitiously recorded bedroom encounter. Added to the two concurring votes, then, this makes a five-four majority in favor of privacy over news specifically involving a sex tape.

It seems, then, that the death notice and celebratory funeral for the Warren and Brandeis privacy tort had come too soon and that, perhaps, Gawker’s First Amendment calls and claims were more self-righteous than right. Despite its near death in the 1970s and 1980s, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, a majority of the Justices on the U.S. Supreme Court had explicitly found privacy viable, even in a case involving a public figure.

___

Listen to Amy Gajda talk with WNYC’s Brian Lehrer about how non-traditional journalists and news outlets, who sometimes skirt the ethical guidelines of the profession, pose a threat to the practice of journalism as a whole—and its protection under the law: