Until 1964 when the Supreme Court decided New York Times v. Sullivan, and extending back many centuries, public officials had the power to put down critics. They could easily win a libel suit because the burden was on the alleged offenders to defend themselves by proving the truth of their assertions, with no consideration for innocent error. The result: a chilling effect on speech. Those in power could bully those without.

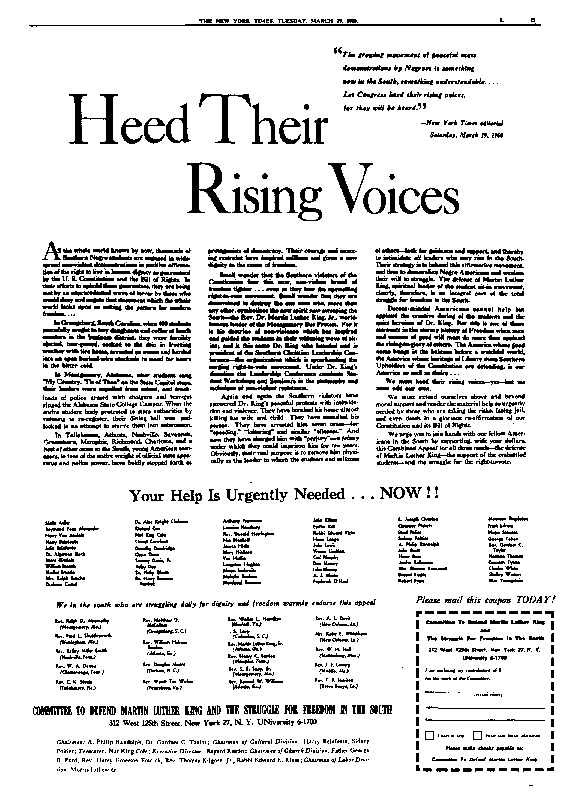

The Supreme Court had an opportunity to reform libel law when it took, New York Times v. Sullivan, involving the police commissioner of Montgomery, Alabama. He claimed that he had been defamed by a full-page advertisement in the Times on March 29, 1960 involving a civil rights incident in Montgomery.

Full-page advertisement in the New York Times on March 29, 1960.

Alabama’s civil libel law was a direct descendant of the Sedition Act of 1798, which the Adams Administration had wielded to put more than a dozen of its critics in jail.

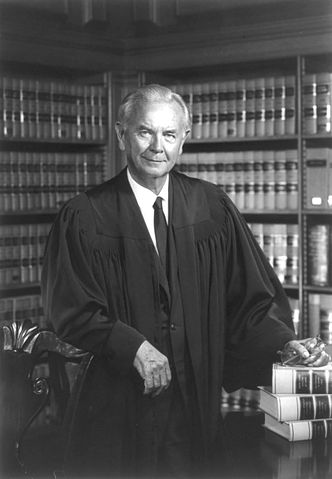

The Court overturned the Alabama libel law and broke sharply from the past, providing broad new protections for political speech. In a self-governing democracy, people had to be free to criticize the public officials who represented them. The justices ruled that the First Amendment protected even the most caustic and vitriolic criticism—“unpleasantly sharp attacks against government and public officials.” Justice William Brennan expressed for the majority the central meaning of the First Amendment: “Thus we consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.” The First Amendment, the Court said, “was fashioned to assure unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people.”

US Supreme Court Justice William Brennan

The Court recognized that the defense of truth was a thin reed upon which to assure robust discussion. Brennan wrote that “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate, and that it must be protected if the freedoms of expression are to have the ‘breathing space’ that they ‘need . . . to survive.’ The Court continued: “Allowance of the defense of truth, with the burden of proving it on the defendant, does not mean that only false speech will be deterred. Even courts accepting this defense as an adequate safeguard have recognized the difficulties of adducing legal proofs that the alleged libel was true in all its factual particulars.”

The resulting chilling effect inhibited public debate and discussion. “Under such a rule, would-be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is, in fact, true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so. They tend to make only statements which ‘steer far wider of the unlawful zone.’ The rule thus dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate. It is inconsistent with the First and Fourteenth Amendments.”

The Court ruled that the First Amendment protected critics from libel actions of public officials in significant ways. The justices changed the burden of proof—instead of speakers and writers having to prove the truth of their assertions, officials would have to prove falsity. And even false statements were protected unless the defendant made them with knowledge that they were false or with reckless disregard for the truth.

New York Times v. Sullivan involved public officials suing for defamation. Three years later, in Curtis Publishing v. Butts and Associated Press v. Walker, the Court began the process of extending the New York Times requirement to cases involving public figures as plaintiffs, reasoning that public figures often wielded as much power and influence as public officials and so should face difficult requirements for winning a libel suit. Today, public figures as well as public officials must prove that a defamatory statement was published with knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth.

Defamation, or libel, is a tort (a civil wrong) for which the aggrieved party may sue for money damages. There is no federal libel law. State libel laws are subject to the First Amendment limitations imposed by the Supreme Court.

Defamation law requires the plaintiff to prove that a defamatory statement is false. Opinion and satire is constitutionally protected because it is not provably false and it cannot be reasonably interpreted as presenting actual facts.

State law provides some additional (and varying) protections for defendants, such as the privilege of fairly and accurately reporting defamatory information from public records and government proceedings.

A plaintiff must prove the following:

- Defamatory language: The communication must injure a person’s reputation, exposing him to hatred, ridicule, or contempt. Typical statements include accusations of crime, negative discussion of a person’s character, criticism of business practices, and disparagement of a commercial product.

- Harm, or damages: The defamatory statement must cause harm, such as to a person’s or corporation’s reputation or to their financial situation.

- Identification: The person must have been identified by name or is otherwise clearly identifiable.

- Published: The defamatory statement must be published or broadcast. Publication can be to just one person (other than the publisher and plaintiff), but libel actions typically involve mass communication.

- Falsity: Public officials and public figures must prove that the defamatory statement was false. Private persons must prove falsity when the defamatory statement involves a matter of public concern. Minor errors such as wrong dates or places are generally not considered substantial enough themselves to meet this standard of falsity as long as the overall statement is substantially true.

- Fault: Even false, defamatory statements are protected under the First Amendment unless the plaintiff can also prove that the statements were published with fault. Public officials and public figures must prove a very high level of fault—that the defendant knew it was false and published it anyway (intentional falsehood) or had a high degree of awareness of probable falsehood and published anyway (reckless disregard). By contrast, a private person must prove a lower level of fault that may vary depending on the state, but not less than negligence or carelessness. Given fault requirements, public officials and public figures have a difficult time winning a libel case; private persons, having to prove only careless false statements, have an easier time.

READ MORE:

Father Candor Anticipates <em>New York Times vs Sullivan</em> Over 250 Years Ago What <em>The Post</em> Teaches Us About Press FreedomTags