Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress

A satiric attack on Jerry Falwell, a Baptist pastor and founder of the conservative group, the Moral Majority, resulted in a major Supreme Court opinion protecting the First Amendment rights of satirists to deliver commentary mocking public figures in America.

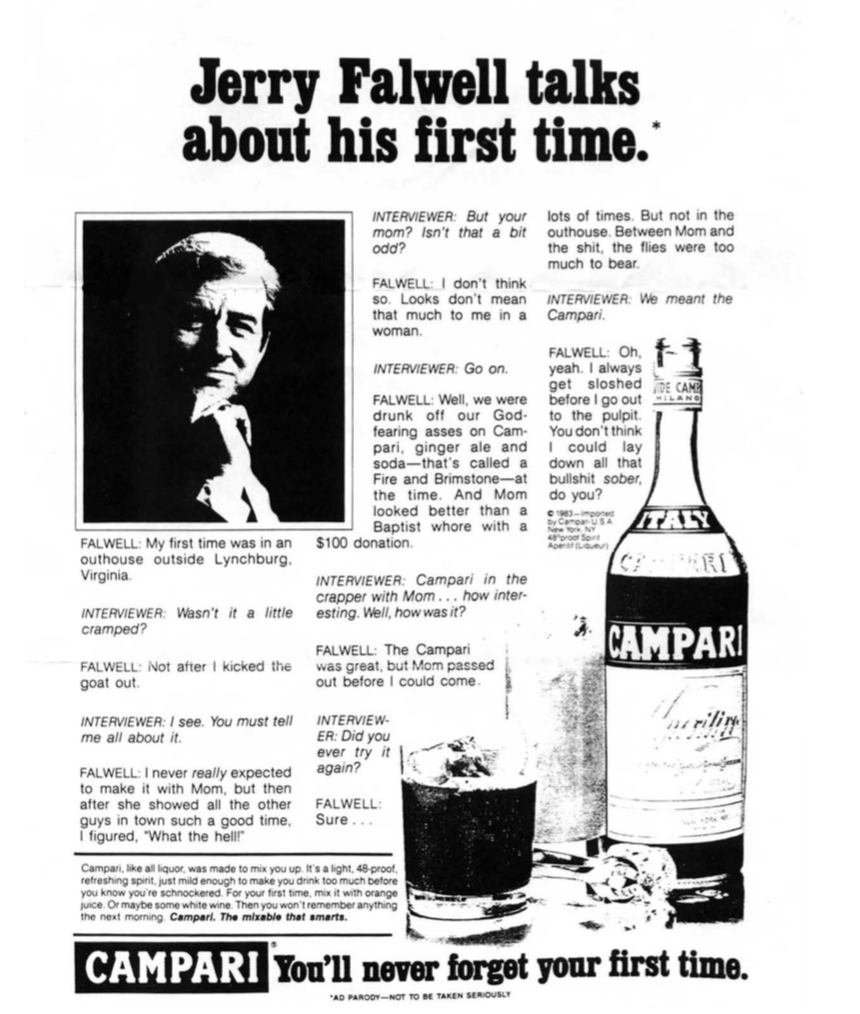

Larry Flynt, the publisher of Hustler Magazine, initiated the conflict in 1983 when he published a parody of a Campari liqueur ad on the inside front cover of his magazine. Flynt parodied a series of Campari ads that played on a sexual double entendre asking celebrities to describe their “first times.” Attacking Falwell’s well-known social conservatism, Hustler presented a fictional interview with Falwell in which he describes having an incestuous encounter with his mother in an outhouse while he was drunk. The parody carried a disclaimer “not to be taken seriously.” The jury had found against Falwell on his libel claim because libel involves false statements of fact and no reasonable person would have believed that the magazine was stating actual facts about Falwell. In other words, readers were in on the joke.

Larry Flynt

But it was no doubt a joke that seared Falwell’s sensibilities, especially given that he was a conservative preacher, and he claimed that the parody was outrageous and was published to intentionally inflict emotional distress on him. Although the Court described the parody as “doubtless gross and repugnant in the eyes of most,” the justices unanimously ruled that the First Amendment protected Hustler and Flynt.

The Court in Hustler Magazine v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988), provided a broad endorsement of the marketplace of ideas. “At the heart of the First Amendment is the recognition of the fundamental importance of the free flow of ideas and opinions on matters of public interest and concern. [T]he freedom to speak one’s mind is not only an aspect of individual liberty—and thus a good unto itself—but also is essential to the common quest for truth and the vitality of society as a whole.”

That imperative carried into the area of satire, the arena today of prominent political commentators like Stephen Colbert and Trevor Noah and many cartoonists. The justices were mindful of the fact that satiric commentary will always cause emotional distress among those attacked. “Were we to hold otherwise, there can be little doubt that political cartoonists and satirists would be subjected to damages awards without any showing that their work falsely defamed its subject. . . The appeal of the political cartoon or caricature is often based on exploitation of unfortunate physical traits or politically embarrassing events — an exploitation often calculated to injure the feelings of the subject of the portrayal. The art of the cartoonist is often not reasoned or evenhanded, but slashing and one-sided. One cartoonist expressed the nature of the art in these words: ‘The political cartoon is a weapon of attack, of scorn and ridicule and satire; it is least effective when it tries to pat some politician on the back. It is usually as welcome as a bee sting, and is always controversial in some quarters.’”

That imperative carried into the area of satire, the arena today of prominent political commentators like Stephen Colbert and Trevor Noah and many cartoonists. The justices were mindful of the fact that satiric commentary will always cause emotional distress among those attacked. “Were we to hold otherwise, there can be little doubt that political cartoonists and satirists would be subjected to damages awards without any showing that their work falsely defamed its subject. . . The appeal of the political cartoon or caricature is often based on exploitation of unfortunate physical traits or politically embarrassing events — an exploitation often calculated to injure the feelings of the subject of the portrayal. The art of the cartoonist is often not reasoned or evenhanded, but slashing and one-sided. One cartoonist expressed the nature of the art in these words: ‘The political cartoon is a weapon of attack, of scorn and ridicule and satire; it is least effective when it tries to pat some politician on the back. It is usually as welcome as a bee sting, and is always controversial in some quarters.’”

The Court explained that there was no precise way to define “outrageousness,” which could result in juries applying their own tastes in a way that punished speakers they didn’t like. “Respondent [Falwell] contends, however, that the caricature in question here was so ‘outrageous’ as to distinguish it from more traditional political cartoons. There is no doubt that the caricature of respondent and his mother published in Hustler is at best a distant cousin of the political cartoons described above, and a rather poor relation at that. If it were possible by laying down a principled standard to separate the one from the other, public discourse would probably suffer little or no harm. But we doubt that there is any such standard, and we are quite sure that the pejorative description ‘outrageous’ does not supply one. ‘Outrageousness’ in the area of political and social discourse has an inherent subjectiveness about it which would allow a jury to impose liability on the basis of the jurors’ tastes or views, or perhaps on the basis of their dislike of a particular expression. An ‘outrageousness’ standard thus runs afoul of our longstanding refusal to allow damages to be awarded because the speech in question may have an adverse emotional impact on the audience.”

The Court ruled that public officials and public figures cannot win a suit for intentional infliction of emotional distress without also meeting the requirement of a libel claim—that the defendant published a false statement with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard for the truth. The ruling all but ruled out a standing alone emotional distress claim by a public figure like Falwell, since satire is understood by the audience as not stating actual facts required in a libel claim.

<em>Hustler Magazine v. Falwell </em>Oyez <em>Hustler Magazine v. Falwell </em>Justia

Tags