By David Rudenstine

This piece was written to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the New York Times v. United States (1971) ruling, popularly known as the Pentagon Papers case. The case was decided on June 30, 1971.

David Rudenstine is the Sheldon H. Solow Professor of Law and Dean Emeritus of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Day the Presses Stopped: A History of the Pentagon Papers Case and The Age of Deference: The Supreme Court, National Security, and the Constitutional Order.

The Pentagon Papers case affirms fundamental values and principles. Truth matters— facts matter. The role of the press in the American governing scheme is to serve the “governed” and not the “governors.” The protection of a “cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press” is essential to a vibrant and strong American democracy. That is the profound and enduring meaning of the case.

I was due in landlord-tenant court at 10 a.m. My legal services clients were withholding their rent payments in response to the landlord’s failure to address basic repairs.

It was Friday, June 18, 1971.

Three days earlier, the United States of America commenced a civil action against The New York Times seeking to enjoin it from continuing to publish a 10-part series on America’s involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1968. The Times reports were based on what became known as The Pentagon Papers, a top-secret, sensitive history of the Vietnam War that former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara authorized in June of 1967.

Daniel Ellsberg, a former Defense Department analyst, had long supported the war but eventually strongly and publicly opposed it. He made the classified documents available to a Times reporter, Neil Sheehan, hoping that the Times’ disclosure of the secret history would outrage the American public and force the government to end the tragic war that had killed so many.

The Times first installment of its serial reports was published on Sunday, June 13th. On Monday night, the government demanded that the Times cease publication of the series. The Times refused. The government sued.

The first installment of the Pentagon Papers series published by The New York Times on June 13, 1971.

From the left, New York Times Managing Editor A.M. Rosenthal, Publisher Arthur Sulzberger, Journalist Hedrick Smith (behind), and Assistant Foreign Editor Gerald Gold review the first installment of the Pentagon Papers series. Wikimedia Commons.

The government’s legal action against the Times dominated the news all week, and had converted tedious government documents into a bestseller. And on Tuesday, June 15th, when federal judge Murray Gurfein enjoined the Times from further publishing the series pending the outcome of the Friday hearing, national attention was riveted on what this new Nixon-appointed judge would do in this block-buster conflict between the government and the press over the press’s right to publish classified national security information.

Because the landlord-tenant courthouse was down the block from where Judge Gurfein would preside, I stopped by the federal courthouse.

When I arrived, the courtroom was jam-packed. Standing room only. Shortly after Judge Gurfein commenced the hearing, the Times lead lawyer, Yale law professor Alexander Bickel, told Judge Gurfein something along the following lines: “Your honor, all week long the government has claimed that if another installment of the Pentagon Papers report appeared, the Republic would collapse. Well, another Pentagon Papers report has appeared, and it is in this morning’s Washington Post, and the Republic still stands”. The courtroom went wild. Cheers, applause, shouting. Once things settled down, Gurfein announced that he would hold a closed door hearing later that day during which the government would present evidence to support its claim that further publication would gravely harm the nation’s security.

Gurfein’s secret hearing ended late Friday night. Very early Saturday morning, Gurfein dictated one of the most remarkable legal opinions any judge wrote during the 15 days of this frantic litigation.

In sum, Gurfein concluded that the government witnesses and documentary evidence failed to prove that further publication of the controversial series would sufficiently injure national security. So, he denied the government a preliminary injunction and dissolved his Tuesday restraining order. In his opinion he wrote: “The security of the Nation is not at the ramparts alone. Security also lies in the value of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.”

Gurfein’s opinion was like the first shots fired at Lexington. The government appealed the Times case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and it commenced proceedings against The Washington Post in the D.C. courts. In uncharacteristic rapidity, on Friday, June 25th, the Supreme Court agreed to hear both cases, and it ordered the lawyers to submit their legal memoranda within 18 hours. Both sides had to argue the matter a few hours later. This all happened on Saturday morning, June 26th. Silence followed. The nation waited. There were no leaks. And then on Wednesday, June 30th, the Court announced its decision.

The nine justices issued 10 opinions and by a vote of 6-3 permitted the newspapers to continue to publish reports based on the government’s secret war history.

There was a short per curiam opinion stating that the government’s evidence failed to meet its “heavy” evidentiary burden. After that Justices Hugo Black, William O. Douglas, William J. Brennan, Potter Stewart, Byron White and Thurgood Marshall wrote individually upholding the ruling. Chief Justice Burger and Justices Harlan and Blackmun each dissented.

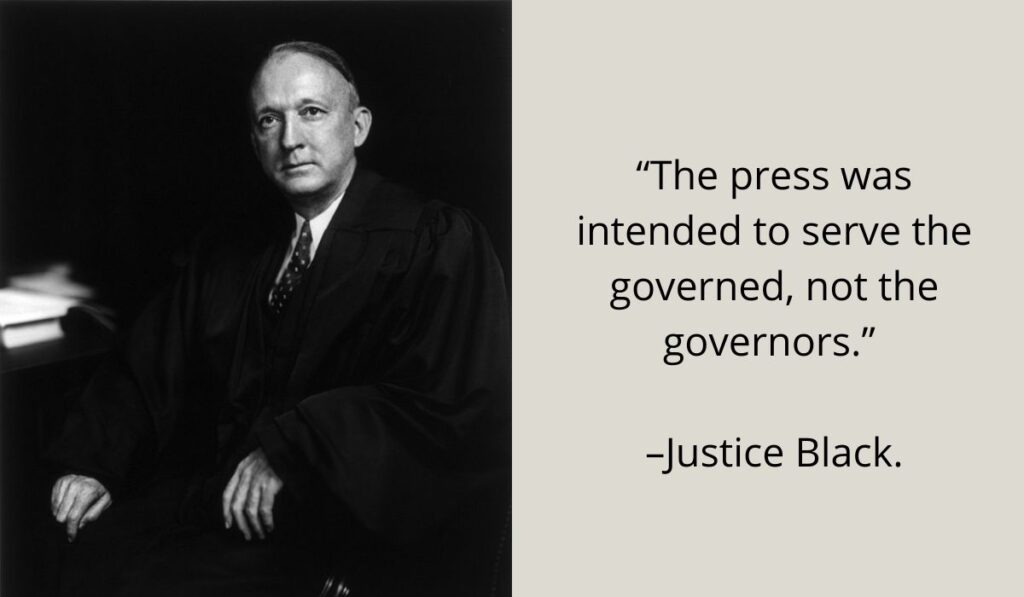

Justice Black’s opinion contained the most memorable lines. “The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government’s power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of the government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.”

Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black was one of the six justices who sided with two newspapers in United States v. New York Times (1971). Library of Congress.

With the ruling in their favor, the newspapers published their Pentagon Papers reports. The case—and the papers—have become a touchstone in American legal history, giving the press national prestige and granting it the status of a fourth branch of government.

So, in retrospect what do we make of this extraordinary moment in American history? Is this episode now a legal antique or does the epic confrontation between the press and the government have contemporary meaning? And if so, what is it?

First, the obvious. The Internet and numerous social media platforms have drained the Pentagon Papers case of most of its technical significance. Today, the multiplicity of outlets accessible to millions has made it very unlikely that a disclosure of classified information allegedly injuring national security would be disseminated only by means of a paper copy, and then in multiple installments released over many days. So, the technical side of the case has largely lost its practical application.

Second, although the per curiam opinion gave a resounding victory to the press, the failure of the majority to rally around a more eloquent statement of values underlying the ruling as expressed by Justice Black in his opinion was a disappointment. And that disappointment was only amplified by Justice White’s opinion – joined by Justice Stewart – that urged the Nixon administration to investigate and possibly prosecute criminal charges against the newspapers.

Those factors – along with the fact that three Court members dissented – prompted concern that the technical legal victory camouflaged an impending assault on press freedoms. In other words, some believed that the victory celebration should be followed by a funeral march.

Nonetheless, this judgment downplaying the significance of the press victory misses several important points. Not the least of which is that, in the late 1980s, the government lawyer who argued the case against the newspapers wrote an op-ed claiming that there was no evidence that the newspaper publications harmed national security.

“During the half century since the Pentagon Papers decision, the national government has commenced only one case in which it sought a prior restraint against a national news magazine.”

The Nixon administration decided that if it could not prevail in securing a prior restraint, it could not prevail in a criminal prosecution against the Times and The Post. So, as disappointing as the per curiam was, it was sufficient to squelch Justice White’s plea for a criminal prosecution of theTimes.

Eloquence is stirring. It can, as Justice Homes wrote a century ago, set “fire to reason.” But eloquence and outcomes are different, and no sane litigant prefers eloquence to winning. Moreover, eloquence is overvalued. An eloquent opinion that sets forth legal standards or rules does not prevent courts from tip-toeing around or seriously qualifying what may have seemed to be a concrete and controlling legal doctrine. Thus, the dismayed critics of the 1971 Pentagon Papers decision place too much emphasis on the capacity of legal doctrine to control subsequent developments, and too little emphasis on the symbolism of a result.

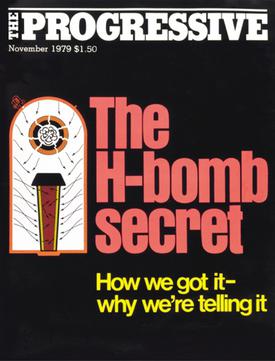

As disappointing as the per curiam opinion was, the Pentagon Papers litigation did discourage government efforts to secure a prior restraint. During the half century since the Pentagon Papers decision, the national government has commenced only one case in which it sought a prior restraint against a national news magazine. In that case, The Progressive Magazine sought to publish an article on how to build an H-Bomb. The initial restraining order was soon dissolved as the substance of the article was found to already exist in the public domain.

The cover of the November 1979 issue of The Progressive, which the United States government attempted to censor.

Those, who at the time questioned the decision’s limitation, overestimated the likelihood of a press victory. The lead prior restraint case was Near v. Minnesota (1931). That was the first time that the High Court squarely confronted the question of whether the government could enjoin the press from publishing information it legally obtained.

In the Spring of 1931, Chief Justice Charles Evan Hughes wrote an opinion on behalf of five members of the Court declaring a Minnesota statute authorizing a prior restraint unconstitutional. The four dissenters were correct when they asserted that the Court was breaking new ground, and that the Supreme Court had not previously reached such an outcome. Chief Justice Hughes conceded that the government could obtain a prior restraint under limited circumstances, and he put forth a well-known example this way: “No one would question but that a government might prevent actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops.” In the Pentagon Papers litigation, the government claimed that its national security considerations were the equivalent of what Chief Justice Hughes had in mind.

Other political considerations suggested the government would prevail. In 1971, the United States was the dominant world power; it was engaged in a long-standing Cold War with the Soviet Union; and its relationship with communist China was strained and uncertain. The United States had global national security interests protected by the Central Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency, along with military bases that ringed the globe. National security interests were front and center, and all branches of the government exercised deference towards the President when national security was arguably implicated. Within that context, an informed observer could understandably predict that the government would win the case against the press because of the deference normally extended to presidential judgments concerning national security.

An informed observer would assume that Justices Black, Douglas, and Brennan would vote against the government, and that Justices Warren E. Burger, John Marshall Harlan, and Harry Blackmun would vote in the government’s favor. Such a cautious assessor might also assume that Justice Thurgood Marshall would vote against the government, which would leave the court split 4-3 with Justice Stewart and White constituting the deciding votes. From this perspective, the outcome in the case depended on how Stewart and White voted, and their votes were uncertain.

Considering all of that, what can one say about the continued significance of the Pentagon Papers case?

Standing behind the bar aboard Air Force One, President Richard Nixon speaks with military and civilian leaders while flying from Bangkok to Saigon for a short visit with commanders and troops stationed in Vietnam. Image by © Wally McNamee/CORBIS

Daniel Ellsberg speaking at a press conference in New York City in 1972. Library of Congress.

The fact that the newspapers won was far more than a legal victory. The outcome affirmed more than any other court opinion had previously done that the press has a vital role in the American governing scheme, even when the nation’s security is implicated.

But those generalizations need unpacking to appreciate the profound significance of the press victory. The press victory meant that the government had the burden of proving it should be granted an injunction. It meant that the strength of the government’s case – and thus the protection of the nation’s security – rested in large part on the effectiveness of the government witnesses and lawyers, as well as the disposition of the judges. It meant that the newspapers should have absolute discretion in deciding what to publish. It gave the press remarkable prestige and stature. The press was not merely a vehicle for passing along the news; it was a fourth branch of government directly implicated in the country’s national security. That is what freedom of the press meant in the Pentagon Papers case.

There is one aspect of the Pentagon Papers largely forgotten that is highly relevant to contemporary America. When the Times first got the papers in March 1971, it worried that the FBI would discover that it possessed the secret history, and would raid its offices searching for the papers. As a result, the Times used fictitious names to rent Hilton Hotel rooms where the reporters and editors worked for three months preparing the 10-part series.

The press was not merely a vehicle for passing along the news; it was a fourth branch of government directly implicated in the country’s national security.

During this three-month period, the Times’s law firm of Lord Day & Lord, whose managing partner was Herbert Brownell Jr., the Attorney General during the Eisenhower administration, told the Times that its possession of the classified papers was unpatriotic and that the newspaper, including the publisher and editors, ran the risk of being criminally prosecuted and convicted. These warnings were taken seriously by the publisher and the executive editor, and yet the Times continued with the project. As for Lord Day & Lord, at the eleventh hour—late on Monday night on June 14—it informed the Times that it would not defend it early the next morning against the government’s lawsuit seeking an injunction.

In the seminal dispute, the nation’s premier newspaper put itself on the line so that it could tell the American people the truth about a war that took over 58,000 American soldier lives and millions of Vietnamese lives. The Times did that because it believed that the truth mattered, and that truth was the sole salvation of a democracy. And while the privately-controlled media is not politically accountable as it functions within a society that values democracy, that very democracy cannot function without that insulated and constitutionally protected press.

The Pentagon Papers case affirms fundamental values and principles. Truth matters— facts matter. The role of the press in the American governing scheme is to serve the “governed” and not the “governors.” The protection of a “cantankerous press, an obstinate press, a ubiquitous press” is essential to a vibrant and strong American democracy. That is the profound and enduring meaning of the case.

David Rudenstine is the Sheldon H. Solow Professor of Law and Dean Emeritus of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University. He is the author of “The Day the Presses Stopped: A History of the Pentagon Papers Case” and “The Age of Deference: The Supreme Court, National Security, and the Constitutional Order.”

Tags