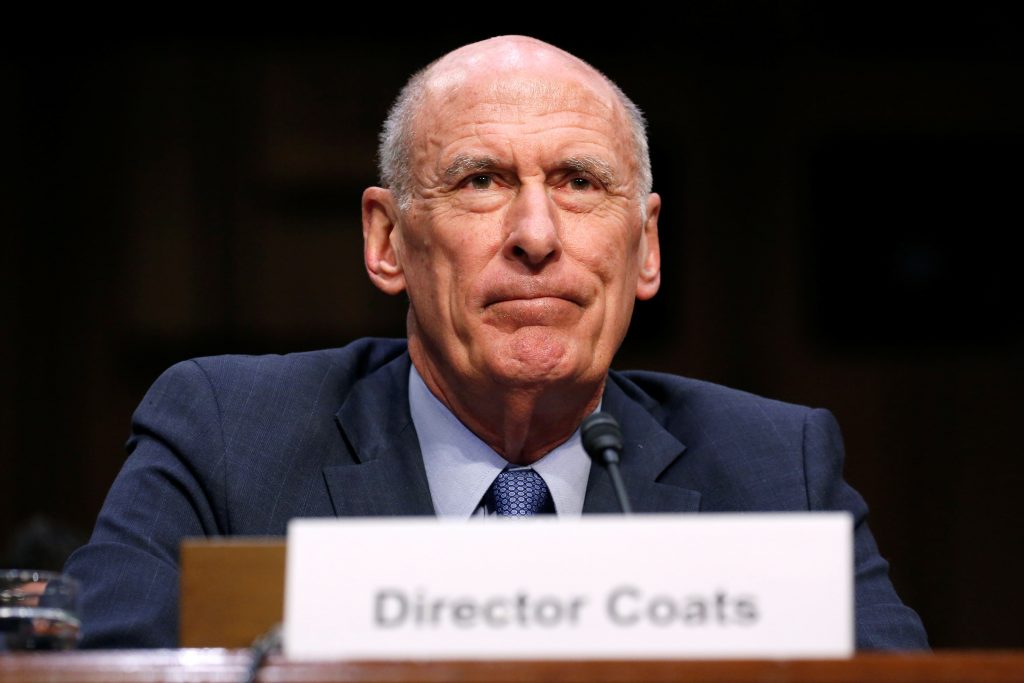

Five former intelligence officials are suing two U.S. intelligence agencies and the Department of Defense, challenging the constitutionality of the agencies’ “prepublication review” system. The prepublication review system requires current and former intelligence agency employees and military personnel to submit for government approval anything they write about their past work.

According to the complaint, Edgar v. Coats, filed in a Federal District Court in Maryland by the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University and American Civil Liberties Union, tens of thousands of submissions are reviewed and arbitrarily censored every year. The complaint contends that the submission and review process violates the First Amendment through a prior restraint on speech, and the Fifth Amendment for failing “to provide government employees with fair notice of what they must submit for prepublication review.”

The complaint alleges the review process is too broad, inconsistent, and slow, that the “dysfunction” of the process leads to self-censorship, and denies the public access to important information about government policy. The plaintiffs allege that manuscript review is lengthy—often taking weeks, months, or even a year to be completed. The manner in which the review process is carried out violates the Fifth Amendment, the complaint contends, because it and that the material censored is oftentimes unnecessary, unexplained, and/or subjective based on the author’s viewpoint. The review process is unjustified, the plaintiffs claim, as it requires former employees to submit their work without regard to the level of their access to sensitive information. They also allege that officials who are less critical of the agencies tend to be given special treatment, and their reviews are “fast-tracked.”

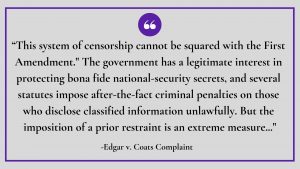

“This system of censorship cannot be squared with the First Amendment. The government has a legitimate interest in protecting bona fide national-security secrets, and several statutes impose after-the-fact criminal penalties on those who disclose classified information unlawfully. But the imposition of a prior restraint is an extreme measure—one that can be justified only in truly extraordinary circumstances and, even then, only when the restraint is closely tailored to a compelling government interest and accompanied by procedural safeguards designed to avoid the dangers of a censorship system. To survive First Amendment scrutiny, a requirement of prepublication review would have to, at a minimum, apply only to those entrusted with the most closely held government secrets; apply only to material reasonably likely to contain those secrets; provide clear notice of what must be submitted and what standards will be applied; tightly cabin the discretion of government censors; include strict and definite time limits for completion of review; require censors to explain their decisions; and assure that those decisions are subject to prompt review by the courts. The prepublication review system, in its current form, has none of these features.”

According to the New York Times, while previous lawsuits have been filed in regards to specific manuscripts, this is the first lawsuit that challenges the entire review system as a whole.

New York Times Reuters The Intercept

History

George H. W. Bush is sworn in as Director of CIA by Justice Potter Stewart (L) as President Gerald Ford (R) looks on, in January 10, 1976. REUTERS/George Bush Presidential Library and Museum/Handout I

The complaint outlines how the prepublication review system has grown since it was created informally in the 1950s through the Office of Security and Office of General Counsel. At the time, only a few former CIA employees sought to publish manuscripts. The review system expanded to cover more individuals and agencies in the 1970s when more people began to write critically about the agencies and their activities. In 1976, in the wake of a Fourth Circuit ruling allowing the CIA to enforce a prepublication review agreement against former employee Victor Marchetti, then-CIA Director George H.W. Bush established the Publications Review Board to review the non-official publications of current employees.

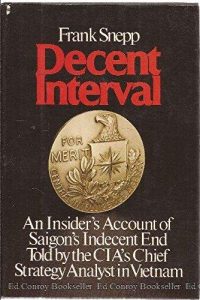

“Decent Interval” by Frank Snepp

Four years later, the Supreme Court ruled in Snepp v. United States that the CIA’s employment agreement that contained prepublication review requirements did not violate free expression rights. The decision allowed the CIA to seize the proceeds earned by Frank Snepp, a former officer who had published a book without submitting it for review.

In the intervening years, intelligence agencies expanded prepublication reviews as a lifetime requirement for former employees as well as current ones. The review process has also expanded to include a broader swath of individuals, including those without access to classified information. At the same time, the review requirements and obligations have become more complex. The amount of material submitted for review has dramatically increased as well, leading to lengthier review times. According to a draft report of the CIA Inspector General obtained by the ACLU and the Knight Institute, the CIA received 43 submissions in 1977, but in 2015, it received 8,400 submissions.

“The Government Had To Approve This Op-Ed”

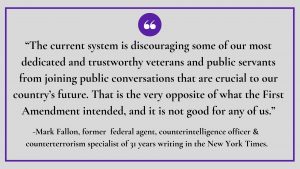

Mark Fallon, a former federal agent, counterintelligence officers and counter terrorism specialist of 31 years and one of the plaintiffs in the suit, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times about the government’s unwarranted and capricious censorship of unclassified material. Fallon wrote a book criticizing the George W. Bush’s administration’s policies around the interrogation tactics used on foreign suspects, and says he was careful to avoid using classified material, instead citing only material from congressional hearings and official investigations that was already public. He submitted his manuscript to the Department of Defense (DOD) for review, a process that was supposed to be completed within 30 working days. Instead, it took the DOD 233 days to return the manuscript and it contained numerous redactions of already published material.

Mark Fallon, a former federal agent, counterintelligence officers and counter terrorism specialist of 31 years and one of the plaintiffs in the suit, wrote an op-ed in the New York Times about the government’s unwarranted and capricious censorship of unclassified material. Fallon wrote a book criticizing the George W. Bush’s administration’s policies around the interrogation tactics used on foreign suspects, and says he was careful to avoid using classified material, instead citing only material from congressional hearings and official investigations that was already public. He submitted his manuscript to the Department of Defense (DOD) for review, a process that was supposed to be completed within 30 working days. Instead, it took the DOD 233 days to return the manuscript and it contained numerous redactions of already published material.

Examples of Review Guidelines

According to the Knight Institute, at least 17 federal government agencies have some form of prepublication review in the form of regulations, policies, and non-disclosure agreements.

ODNI Pre-Publication Review Guidelines CIA Publications Review Board Summary Defense Office of Prepublication and Security Review

Tags