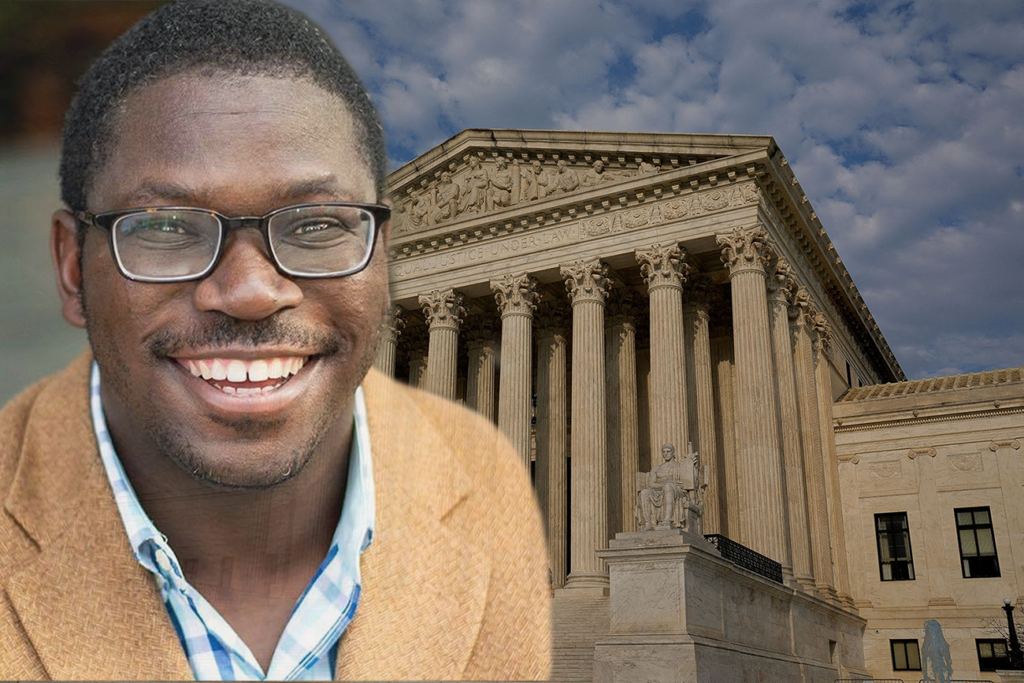

Donald Sherman is the executive vice president and chief counsel at Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), the non-profit organization that, in September 2023, filed the novel challenge to former President Donald Trump’s candidacy in Colorado, citing his actions on Jan. 6, 2021.

The challenge, which was brought on behalf of four Republican voters and two unaffiliated voters, claims Trump violated Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, a Civil War-era provision that bars someone from holding any office if they had “taken an oath” to “support the Constitution” and then “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” against it.

Several such legal challenges were filed in states across the country. And in a 4-3 decision in December, the Colorado Supreme Court was the first in history to disqualify a presidential candidate from the ballot under the provision.

“We do not reach these conclusions lightly,” the decision stated. “We are mindful of the magnitude and weight of the questions now before us. We are likewise mindful of our solemn duty to apply the law, without fear or favor, and without being swayed by public reaction to the decisions that the law mandates we reach.”

Trump appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case in January, arguing that the provision does not apply to the president, that Jan. 6 was not an insurrection, and that he did not “engage” in the attack on the Capitol but was merely exercising his freedom of speech. During oral arguments on Feb. 8, the Supreme Court appeared skeptical of CREW’s argument.

First Amendment Watch spoke with Sherman about his organization’s challenge, in which he reflected on the Supreme Court’s oral arguments, discussed the importance of the court system to consider constitutional violations, no matter how novel, and warned of the effects on democracy if Trump is not held accountable.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

FAW: Can you tell me about the 14th Amendment and intentions of its writers, and how it’s been used previously to disqualify candidates?

DS: Section 3 of the 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868 and it bars people who took an oath to the Constitution, as a state or federal officer, and engaged in insurrection, like the Constitution states, from holding such offices in the future. It was used most frequently in the aftermath of the Civil War to prevent insurrectionists from entering positions in state and federal government. So then we get to Jan. 6. There’s widespread consensus across the political divide that Jan. 6 was an insurrection in the aftermath of the attack on the Capitol, and my organization brought litigation on behalf of three New Mexico residents to remove one official who engaged in the insurrection, Couy Griffin, who was a county commissioner in Otero County, New Mexico, and that was using this provision. So that was the first successful trial to enforce Section 3 of the 14th Amendment in more than 155 years. Obviously the second successful trial was the trial that we brought in Colorado, which did not succeed at the trial level but succeeded on appeal to the Colorado Supreme Court in disqualifying former President Trump based on his role in the Jan. 6 insurrection.

FAW: What sparked the organization’s involvement and its plan to file a challenge in Colorado? Who devised this strategy?

DS: Our team and I did. The effort really started in the aftermath of our victory in New Mexico. Our team started thinking about what states had good state law in order to bring a challenge on behalf of voters. As you may know, Article II gives states broad authority to oversee the administration of elections and so these types of challenges are the province of state law. And then when former President Trump announced that he was running for federal office again, it provided a vehicle in order to bring an enforcement action against the former president, based on Section 3. So we started looking at what states have state law vehicles to bring a ballot challenge on behalf of voters, as well as what states are early enough in the primary calendar to bring such an action and have it get resolved, potentially, up to and including the U.S. Supreme Court, before most states had voted in their primaries. And so that process really sort of narrowed the map to Colorado.