New York’s GOP and various counties have challenged the constitutionality of the state’s Even Year Election Law (EYEL) in federal court, claiming the law violates the First Amendment and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The law, passed in 2023, moves local elections to even years to coincide with presidential and statewide elections. Proponents of the law argue that moving the elections to even years increases voter turnout, but opponents argue that the change deepens the state’s already Democratic majority and top-of-the-ticket candidates would overshadow those found lower on the ballot.

“The EYEL violates the First Amendment because it actually and intentionally imposes severe burdens on candidates’ core political speech,” the complaint, filed by Brewer, Attorneys & Counselors law firm on Dec. 29, argued. “By mandating the consolidation of local races onto ballots dominated by federal and state contests without the ability of political subdivisions to opt out, the EYEL deprives local candidates of a meaningful opportunity to convey their messages to voters by pushing their races to the bottom of what will become exceedingly long ballots.”

The amended complaint follows a previous lawsuit filed in state court that was rejected by the New York State Court of Appeals in October. That court held that “there is no express or implied [state] constitutional limitation on the Legislature’s authority to enact the Even Year Election Law.”

The lawsuit not only seeks a declaration from the court that the law is unconstitutional, but also requests an order barring EYEL enforcement and an option for localities to opt-in or out.

In the state’s motion to dismiss the amended complaint, New York Attorney General Letitia James argues the case lacks merit to succeed on both the First Amendment and Voting Rights Act claims.

“Candidate Plaintiffs allege they will be outspent by national campaigns and their voices will be crowded out,” the Jan. 12 motion stated. “But these concerns do not implicate the First Amendment, which does not guarantee a level playing field in the marketplace of ideas.”

First Amendment Watch spoke with William A. Brewer III, the lead attorney on the case. Brewer has experience in First Amendment litigation and previously spoke to First Amendment Watch when he was the lead attorney for the National Rifle Association (NRA) in its lawsuit against ex-New York state Department of Financial Services Superintendent Maria Vullo in 2018. The NRA had claimed she violated the organization’s free speech rights by allegedly coercing and threatening banks and insurers to sever business relationships with the gun group after the school shooting in Parkland, Florida where 17 students and staff members were killed. In a unanimous decision in 2024, the Supreme Court reversed a lower-court decision tossing out the NRA’s lawsuit, noting that “the critical takeaway is that the First Amendment prohibits government officials from wielding their power selectively to punish or suppress speech.”

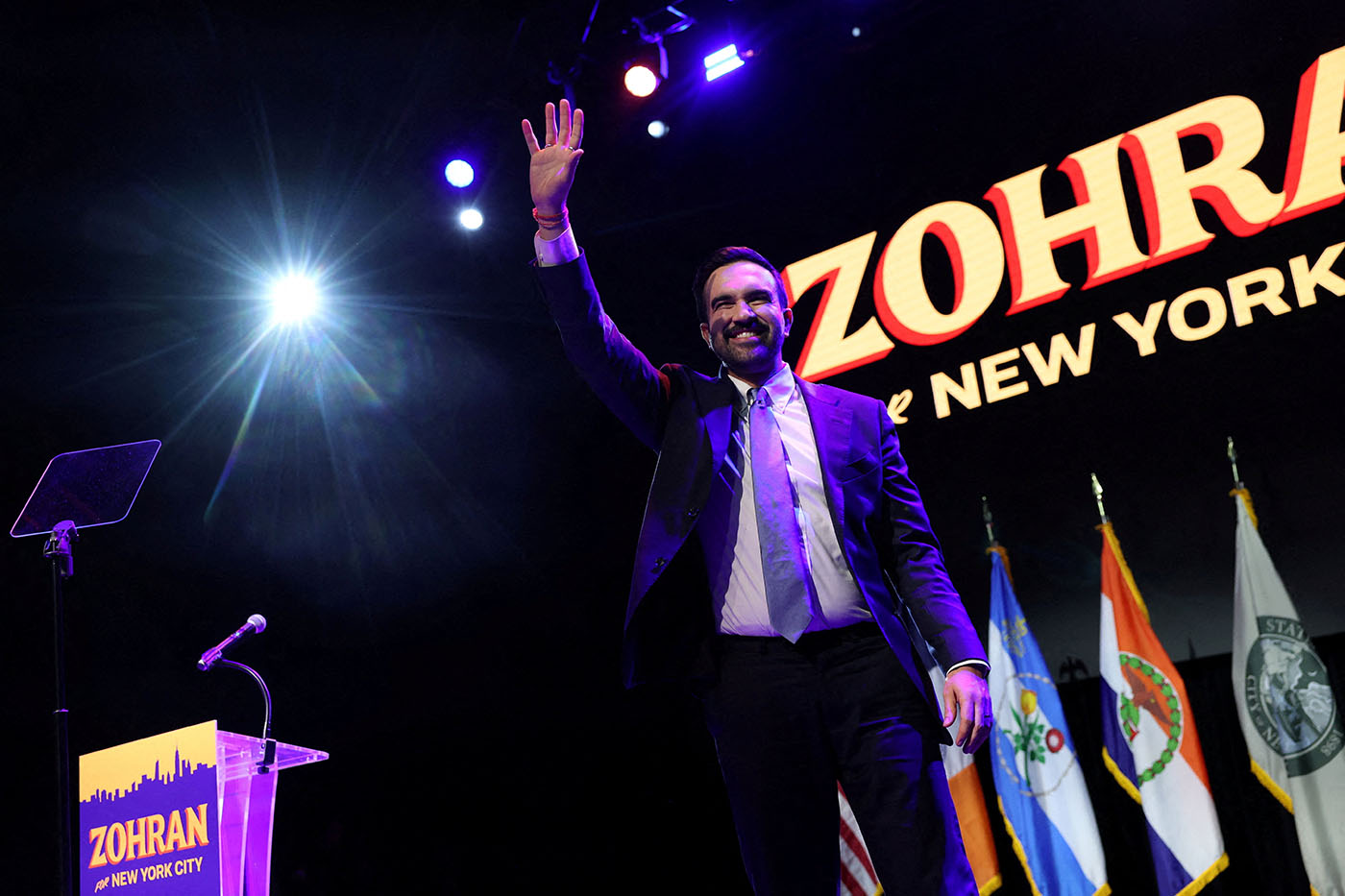

In this interview, Brewer discussed the First Amendment arguments in the challenge to the EYEL, explained why he disagrees with the state, and argued that campaigns like that of New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani are representative of the importance of odd-year elections.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

FAW: What is New York’s Even Year Election law? How does it change how New Yorkers vote in local elections?

Brewer: Most local elections occur on an “odd cycle,” meaning in November, in the state of New York, that they occur in odd years. The reason for that really goes back to the late 1890s when what was then the Progressive Party and a reform movement intended to break political corruption. Almost universally, the solution was seen as [a need] to separate out the important issues that are debated and ultimately decided in local elections into odd years so that they would have their own space in the town square to communicate with voters about those important issues, and then statewide and national elections would go into even years. It not only worked, it swept the nation. Virtually every state, until just recently, had separated most local elections — city, county, towns, school boards and the like — into odd year elections versus even years, which are dominated by, of course, presidential races, but other federal elections, as well as statewide elections. It was perfectly aimed to solve the problem that it was intending to solve. And you saw a replication of that just recently in New York City, where you had a very consequential candidate who became the candidate for the Democratic Party. [Mayor Zohran Mamdani is] credited largely with turning out more people for a local odd year election than had been turned out since John Lindsay, who was such a consequential candidate running as a Liberal Party candidate who turned out [nearly] two and a half million people for that election. And that was extraordinary, because back then you only had one day to vote. Now you have several. But the fact is, when the issues are significant, when the candidates are attractive, and the people who care about those issues are informed, they come to the ballot box.

Everywhere outside of New York City, the Even Year Election Law requires now that all of those local elections move from odd years to even years, and they will now compete for messaging, space and for attention of voters to get the information that is so important to those voters. They’ll be competing in the 2028 presidential election cycle. Good luck, if you’re running for county executive in Onondaga County, getting the attention of your voters. And so that’s unfortunately not only what will be the effect of the Even Year Election Law, it’s actually the intent. All of a sudden, what was from coast-to-coast seen as the solution to the corruption that came when Albany ran New York, and all party politics were being decided at state and national level, is now back. You see this polarized environment where everybody’s trying to reinforce whatever assets they have here in New York, just like the Democrats trying to break through in counties where the Republicans have typically done a more effective job communicating with the local population about what solutions they propose, especially in counties like Nassau and Suffolk, but others too, that are Republican strongholds that are of significant size, power, wealth.

Republicans are doing it in Indiana and are frustrated that they can’t get control, they can’t break through the Democratic success in Indianapolis. You’re seeing it in Kansas, where Republicans are trying to impose an Even Year Election Law because it’s a deep red state, but Democrats are successful, typically, in electing candidates who represent choices that better suit the needs of the people in Lawrence, Kansas or in Topeka. And so all of a sudden, what was great for well over 120 years — more in many places — is now being politicized, and people are changing the election system in order to find a way to break down the success that their opposition party has had in certain places.

The Supreme Court just ruled a couple of weeks ago in Bost that candidates have standing, and the First Amendment is here to protect candidates from non-natural, non-necessary burdens that are being orchestrated in an effort to interrupt the free flow of information between the candidates and their constituents, and that’s exactly what’s going on here.

Think of the anomaly of this. I’m a Democrat, but I represent the Republican Party in this instance, because it’s a First Amendment issue, and we are associated with First Amendment advocacy. The majority, the overwhelming majority of the people who are Democrats live in the five boroughs of New York, in the state of New York. The overwhelming majority of the people who voted for the EYEL to be imposed statewide are actually assembly persons and senators out of the five boroughs. Their constituents rejected an EYEL for the five boroughs in New York, and therefore will continue to have their elections on odd years. And lo and behold, one of the people who was sophisticated enough to understand the importance of that was the now mayor of New York, who came out against Proposition 6, the EYEL for the five boroughs. He wisely came out against it because he recognized that if he was trying to get elected in 2028, probably wouldn’t have a very good chance competing against the top of the ticket. And yet, this consequential politician, this effective campaigner, but who was not just an effective advocate for himself, more importantly was an effective advocate for the changes he wanted to make and the things he believes New York can be and should be. That’s what got him the election.