President Trump and his team want to ‘open up’ libel laws. The goal: to make it easier to sue media organizations for unfavorable coverage. But there is little that the President can actually do to change the libel laws. There is no federal law on libel. State laws control libel, and all such laws are subject to stringent First Amendment protections for the press and other speakers that the Supreme Court has imposed through cases such as the landmark New York Times v. Sullivan decision in 1964. However, threats to loosen the libel laws is noteworthy as part of a larger effort to criticize the press and attack its credibility. For news, analysis, history & legal background read on.

News & Updates

January 10, 2017: After a Hiatus, Libel Law Changes Once Again in the News

President Trump reiterated the need to change the nation’s libel laws. “Our current libel laws are a sham and a disgrace and do not represent American values or American fairness,” the President said at a White House meeting.

New York TimesApril 30th, 2017: Post Trump Libel Tweets, Staff Admits Changing Libel Law on the Table

In an interview on “This Week” Sunday, Trump’s chief of staff, Reince Priebus, stated the news media should “be more responsible with how they report the news” and confirmed the administration was considering strengthening libel laws.

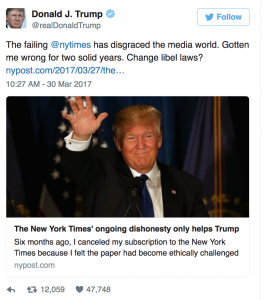

ABCNewsMarch 30, 2017: Trump Tweets about Changing Libel Laws with NYT Reference

February 26, 2016: Donald Trump Pledges to Change Libel Laws

The Republican Presidential candidate said he would “open up our libel laws so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money.”

PoliticoNovember 13, 2016: Can Donald Trump “Open Up” Our Libel Laws?

The New York Times analyzes whether the President-Elect could carry out his promise to make the libel laws more advantageous to people suing about unfavorable stories.

New York TimesNovember 10, 2016: Floyd Abrams Says Media Should Consider Suing Trump

America’s most famous First Amendment lawyer has this surprising message: “Press lawyers ought to bear in mind that if things get rough, if the relationship is one of constant denigration and threats, it may be time for journalists to think about using libel laws in a way that is constitutional.”

Hollywood ReporterSeptember 14, 2016: Gallup Poll Shows Low Trust in Press

A Gallup Poll shows that only 32 percent of Americans have a “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust in the press. This compares to 72 percent in 1976, following the media’s generally admired investigative reporting into Watergate and the Vietnam War.

GallupHistory & Legal Cases

Donald Trump’s History of Libel Suits

The Media Law Resources Center examines seven libel cases brought by Donald Trump and his companies.

Media Law Resource Center___

Defamation, or libel, is a tort (a civil wrong) for which the aggrieved party may sue for money damages. There is no federal libel law. State libel laws are subject to the First Amendment limitations imposed by the Supreme Court.

In New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), the Supreme Court recognized that protection of reputation could impact the freedom of speech and press. To protect expression, the Court imposed constitutional rules that make it very difficult for a plaintiff to make a successful libel claim.

Defamation law requires the plaintiff to prove that a defamatory statement is false. Opinion and satire is constitutionally protected because it is not provably false and it cannot be reasonably interpreted as presenting actual facts.

State law provides some additional (and varying) protections for defendants, such as the privilege of fairly and accurately reporting defamatory information from public records and government proceedings.

A plaintiff must prove the following:

- Defamatory language: The communication must injure a person’s reputation, exposing him to hatred, ridicule, or contempt. Typical statements include accusations of crime, negative discussion of a person’s character, criticism of business practices, and disparagement of a commercial product.

- Harm, or damages: The defamatory statement must cause harm, such as to a person’s or corporation’s reputation or to their financial situation.

- Identification: The person must have been identified by name or is otherwise clearly identifiable.

- Published: The defamatory statement must be published or broadcast. Publication can be to just one person (other than the publisher and plaintiff), but libel actions typically involve mass communication.

- Falsity: Public officials and public figures must prove that the defamatory statement was false. Private persons must prove falsity when the defamatory statement involves a matter of public concern. Minor errors such as wrong dates or places are generally not considered substantial enough themselves to meet this standard of falsity as long as the overall statement is substantially true.

- Fault: Even false, defamatory statements are protected under the First Amendment unless the plaintiff can also prove that the statements were published with fault. Public officials and public figures must prove a very high level of fault—that the defendant knew it was false and published it anyway (intentional falsehood) or had a high degree of awareness of probable falsehood and published anyway (reckless disregard). By contrast, a private person must prove a lower level of fault that may vary depending on the state, but not less than negligence or carelessness. Given fault requirements, public officials and public figures have a difficult time winning a libel case; private persons, having to prove only careless false statements, have an easier time.

Analysis & Opinion

July 11, 2017: Libel Laws Not Easy to Alter

Adam Chiara writes in the Hill that, though there has been a great deal of discussion about changing libel law, not much can be done because libel is a matter of state law. “Additionally, the Supreme Court has placed constitutional limits on how states can define libel. To change that would require either the Supreme Court to overrule it or a constitutional amendment.” Social media increasingly pushes the boundaries of how we define ‘actual malice’ and therefore libel, so there might be some movement in the future – if various constituents can agree.

The HillNPR Interviews Bruce Sanford, a libel law expert. Sanford: “If you don’t like speech, the answer is not to censor that speech or to try to silence it. What our traditions call for is more speech.”

May 4, 2017: Would Trump Lose If He Loosened Libel Laws?

Writing in the Daily Beast, Susan Seager says “if the Supreme Court weakened protections for political speech, then Trump might lose a lawsuit filed against him by three protesters who claim that he incited violence against them by shouting to his supporters “get ’em out of here” at a March 2016 rally in Kentucky.” Proving actual malice is tricky she adds. Trump himself has filed seven libel or other speech-related lawsuits in the past 30 years, and two of those cases were dismissed because he could not prove actual malice.

Daily BeastTags