By Soraya Ferdman

On June 7th, the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan, Southern Division dismissed a First Amendment challenge filed against the city of Detroit by a group of anti-abortion protesters.

The case offers an interesting look at how courts balance public safety concerns against the right to protest.

In July of 2019, Detroit hosted the second round of debates in the Michigan Democratic presidential primary. The debate was sponsored by CNN and located in the Fox Theatre, a venue owned by the private company, Olympia Entertainment.

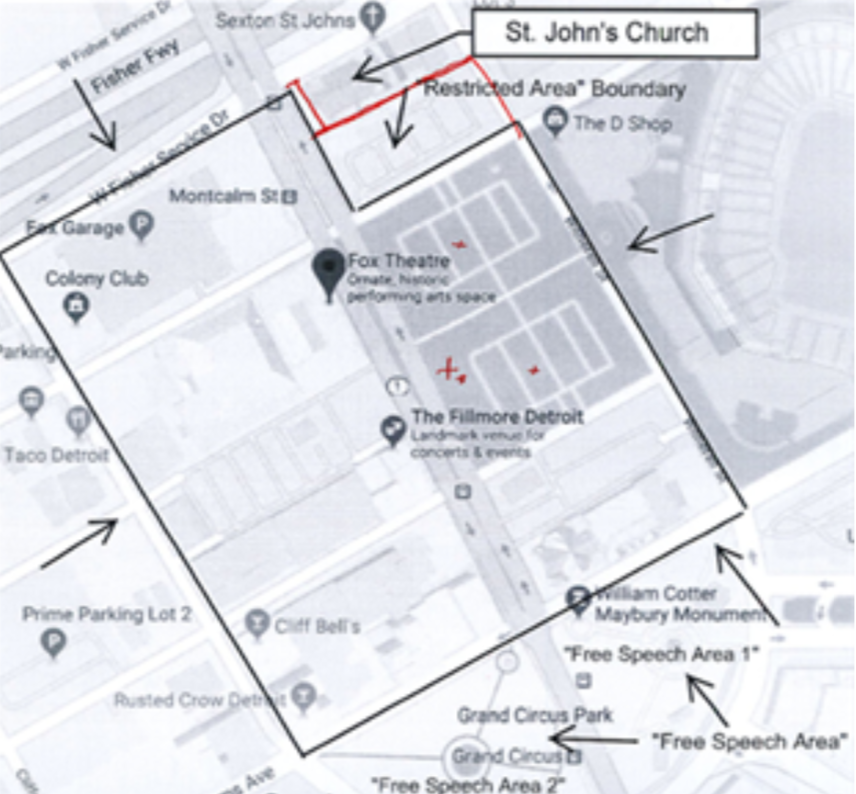

In order to ensure the safety of the candidates, the City of Detroit Police Department, in conjunction with CNN, Olympia Entertainment, the United States Secret Service, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Michigan State Police blocked-off an eight-block area around the venue (see image below).

Map of the area around Fox Theatre, including the contested restricted area around the venue. (Image from Court Documents)

The only people allowed inside the restricted area were individuals with credentials issued by CNN, composed of a select group of voters that CNN planned to use as background for video footage. Those who wanted to protest near the event were led to a free speech area set up in Grand Circus Park outside of the restricted zone.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld the use of buffer zones during protests, as long as the area does not burden more speech than is necessary to serve a significant government interest. Many of the major cases, such as Madsen v. Women’s Health Center, Schenck v. Pro-Choice Network of Western New York, Hill v. Colorado, involve buffer zones outside of abortion clinics. In this case, an anti-abortion group was challenging the restricted area outside of the Michigan Democratic debate.

In their lawsuit, the anti-abortion group Created Equal claimed that the area the city chose to restrict was unnecessarily large, and that the police enforced the restrictions in a viewpoint discriminatory manner.

Both the Tenth and Second Circuit Courts have upheld similar restrictions outside of high-profile political events, such as a restricted zone outside a NATO conference in 2007(Citizens for Peace in Space v. Colorado), and during the 2004 Republican National Convention in New York City (Marcavage v. City of New York).

In this case, the court found that Detroit’s restricted zone around the Democratic debate was appropriate given the security concerns.

“There is no First Amendment requirement that protestors be given direct access to high-profile figures,” the court wrote, adding that “…in the case of presidential candidates, several of whom had received death threats, security considerations are heightened, and alternative means of communication outside of person-to-person communication must be considered adequate.”

Still, Created Equal insisted that the police enforced the restricted zone in a discriminatory manner. For example, the group took issue with the fact that a group of supporters were let inside a portion of the restricted area (a parking lot next to the building) while they were relegated to a far-a-way park.

The problem with this argument, the court explained, was that it was CNN—and not the city—who had arranged for the supporters to stand in the parking lot. The police were not applying a policy unevenly to one group over another, they were only there to ensure that only individuals with the credentials issued by CNN could enter the restricted zone.

Notably, the court also dismissed the claim that the police had violated the First Amendment when they separated the demonstrators in the park by political ideology. Created Equal had argued that this prevented them from persuading left-wing organizers to their cause.

“In this case, the police officers examined the content of each protest group’s speech only to determine which side of the park they should stand on to best maintain safety and order. There is no evidence that the City or any individual officer was motivated by a disagreement with any protest group’s viewpoint. The City’s justification was therefore content-neutral because it ‘serve[d] purposes unrelated to the content of expression’,” the opinion stated.

Altogether, the case is useful for cities planning to use restricted zones to ensure safety at a high-profile event. A city that fails to apply policies consistently might have less luck than Detroit in warding off a First Amendment challenge by unhappy protesters.

Tags