Re-printed with permission by First Amendment News

Stephen Rohde is a constitutional scholar, writer, and retired civil rights lawyer. He is the author of “American Words of Freedom: The Words That Define Our Nation” (2001) and “Freedom of Assembly” (2005), and co-author of “Foundations of Freedom: A Living History of Our Bill of Rights” (1991).

Stephen Rohde is a constitutional scholar, writer, and retired civil rights lawyer. He is the author of “American Words of Freedom: The Words That Define Our Nation” (2001) and “Freedom of Assembly” (2005), and co-author of “Foundations of Freedom: A Living History of Our Bill of Rights” (1991).

“At the very least, our cases recognize that disciplinary rules governing the legal profession cannot punish activity protected by the First Amendment.” — Justice Anthony Kennedy, Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada (plurality opinion, 1991)

“I agree with much of [the dissent of] THE CHIEF JUSTICE . In particular, I agree that a State may regulate speech by lawyers representing clients in pending cases more readily than it may regulate the press.” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor concurring, Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada.

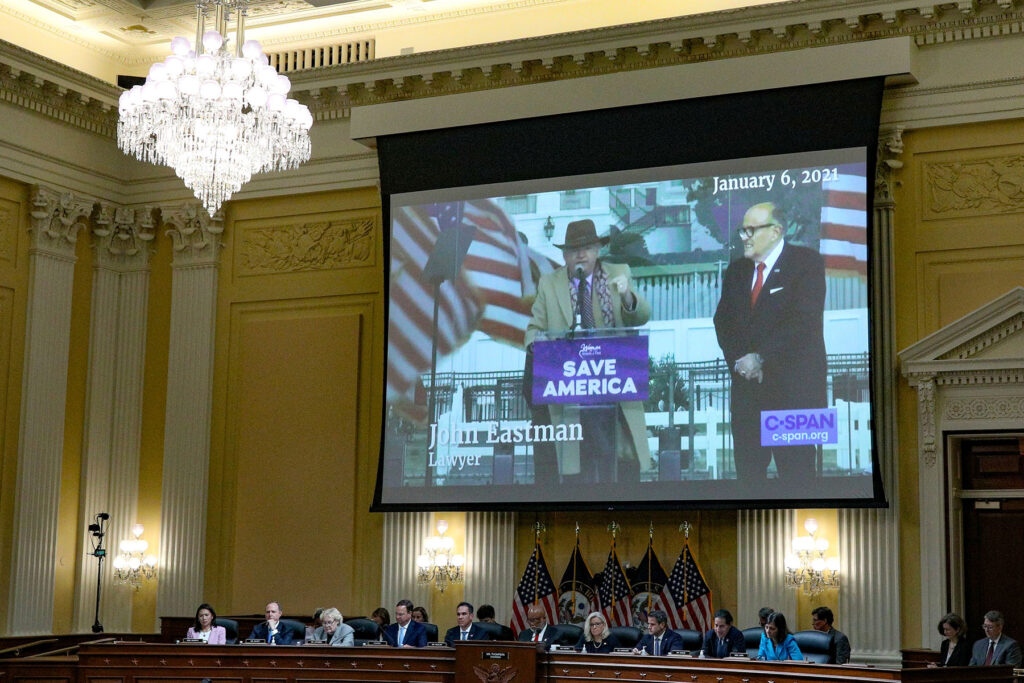

Among the various lawyers who enabled Donald Trump to threaten the peaceful transition of power following his defeat in the 2020 election, John Eastman (a former law clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas) is currently facing disciplinary proceedings in California that could lead to his disbarment. But could he escape accountability by invoking the First Amendment as his shield?

Last January, counsel for the California State Bar filed a comprehensive 34-page complaint charging Eastman with eleven violations of fundamental ethical standards Eastman swore to uphold. The allegations were devastating.

Eastman charged with serious ethical violations

Based on “credible sources and numerous court rulings,” the State Bar alleges that by December 9, 2020,

[Eastman] knew, or was grossly negligent in not knowing, that there was no evidence upon which a reasonable attorney would rely of election fraud or illegality that could have affected the outcome of the election, and that there was no evidence upon which a reasonable attorney would rely that the election had been ‘stolen’ by the Democratic Party or other parties acting in a coordinated conspiracy to fraudulently ‘steal’ the election from Trump.Nevertheless, until at least January 6, 2021, Eastman continued “to work with Trump and others to promote the idea that the outcome of the election was in question and had been stolen from Trump as the result of fraud, disregard of state election law, and misconduct by election officials.” (See Eastman memo.)

As a result, the State Bar alleges that Eastman violated his obligations as an attorney in two ways:

- The first charge is that Eastman “provided legal advice, formulated legal strategies, and engaged in litigation” alleging election fraud. In that regard, he either knew such advice and legal strategies were false or he “was grossly negligent” in not knowing. Furthermore, he promoted such false information by way of “public statements.”

- The second charge concerns “misinterpretations” of historical sources and law review articles that Eastman either “knew or was grossly negligent in not knowing” were “fundamentally flawed.” Thereafter, he “proposed actions based on legal advice regarding the unilateral authority of the Vice President to disregard or delay the counting of electoral votes.” Here again, it is alleged that “he knew, or was grossly negligent in not knowing,” that such counsel “was contrary to and unsupported by the historical record” and relevant precedents,” including those related to the Electoral Count Act and the Twelfth Amendment. It is further alleged that “no reasonable attorney with expertise in constitutional or election law would have concluded that the Vice President was legally authorized to take the actions” proposed by Eastman.

Eastman raises federal and state constitutional free speech protections

In his 111-page response, as set out by his attorneys Randall A. Miller and Zachary Mayer, Eastman denies any wrongdoing. He also asserts sixteen affirmative defenses, including that “the First Amendment and its California counterpart provide absolute protection for political speech and legal opinion given in good faith on a matter of public importance.” In support of his defense, Eastman cites the leading case of Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada (1991) in which four Supreme Court justices stated, “disciplinary rules governing the legal profession cannot punish activity protected by the First Amendment, and [the] First Amendment protection survives even when the attorney violates a disciplinary rule he swore to obey when admitted to the practice of law.”

Eastman argues that as was the case in Gentile, “this case involves punishment of pure speech in the political forum,” and like Nevada in Gentile, California here “seeks to punish the dissemination of information relating to alleged governmental misconduct, which only last Term we described as ‘speech which has traditionally been recognized as lying at the core of the First Amendment.’”

He also argues that his “actions in litigating election disputes on behalf of his client, in speaking about illegality and fraud in the conduct of the election, and in petitioning Vice President Pence to accede to requests from more than a hundred state legislators for a brief delay in the elector vote counting process to assess the impact of such illegality and fraud on the election results, fall squarely within the right to petition protected by the First Amendment.”

Court ruling excluding expert witness frames the First Amendment issue

Eastman designated Rebecca Roiphe, a law professor and Director of the Institute for Professional Ethics at New York Law School, and coauthor of “Lawyers and the Lies They Tell,” published in the “Washington University Journal of Law & Policy” (2022), as an expert witness to testify as to the limitations imposed by the First Amendment on disciplinary proceedings against lawyers. (Watch for Part 2 in this series, “Devil’s Advocate: Why Is a Prominent Ethics Professor Defending John Eastman on First Amendment Grounds?”)

In a pre-trial motion, State Bar Court Judge Yvette D. Roland upheld the State Bar’s objection and excluded Roiphe. She ruled that an expert is not authorized to “give opinions on matters which are essentially within the province of the court to decide.” She acknowledged that “[d]isciplinary rules governing the legal profession cannot punish activity protected by the First Amendment,” and that “even when an attorney violates an ethical rule that he or she swore to obey, the First Amendment protection remains,” citing Gentile. “Nevertheless, knowingly false statements and false statements made with reckless disregard of the truth do not enjoy constitutional protection ‘because there is no constitutional value in such false statements of fact.’ These statements may be the basis of attorney discipline,” citing Ramirez v. State Bar (Cal., 1980).)

Consequently, Judge Roland found that “Roiphe’s testimony will be of no benefit to the court—the court will determine if Respondent’s statements warrant First Amendment protection. Indeed, whether Respondent made false statements and if those statements were made knowingly or with reckless disregard of the truth, are issues that fall within the court’s purview.”

Ramirez is important in this context. It held that courts have “inherent power to regulate the practice of law and discipline members of the bar when such discipline is warranted.” Citing a case where an attorney made defamatory or disrespectful statements in pleadings or other court papers, the court rejected the argument that “outrageous” and “unwarranted” statements concerning a justice of this court were protected by “free speech” considerations.

In the California Supreme Court’s unsigned majority opinion, four of the seven justices added: “The United States Supreme Court, in addressing First Amendment protections of false statements made with reckless disregard for the truth, stated that ‘[c]alculated falsehood falls into that class of utterances which ‘are no essential part of any exposition of ideas, and are of such slight social value as a step to truth that any benefit that might be derived from them is clearly outweighed by the social interest in order and morality . . . .’ Hence the knowingly false statement and the false statement made with reckless disregard of the truth, do not enjoy constitutional protection.”

First Amendment didn’t protect Rudy Giuliani

In seeking to exclude Roiphe, the State Bar took the opportunity to draw Judge Roland’s attention to a 2021 New York appellate court ruling (Matter of Giuliani (NY App. Div. 2021) in which another Trump lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, challenged his temporary suspension, pending a full trial, on the same grounds that the investigation into his conduct violates his First Amendment rights.

The court rejected his argument. Citing the Gentile decision, it held that this “disciplinary proceeding concerns the professional restrictions imposed on respondent as an attorney to not knowingly misrepresent facts and make false statements in connection with his representation of a client. It is long recognized that “speech by an attorney is subject to greater regulation than speech by others . . . Unlike lay persons, an attorney is ‘a professional trained in the art of persuasion.’ . . . As officers of the court, attorneys are ‘an intimate and trusted and essential part of the machinery of justice’ . . . In other words, they are perceived by the public to be in a position of knowledge, and therefore, ‘a crucial source of information and opinion.’”

The New York court added that “[t]his weighty responsibility is reflected in the ‘ultimate purpose of disciplinary proceedings [which] is to protect the public in its reliance upon the integrity and responsibility of the legal profession.” While the court acknowledged “there are limits on the extent to which a lawyer’s right of free speech may be circumscribed, these limits are not implicated by the circumstances of the knowing misconduct that this Court relies upon in granting interim suspension in this case.”

The trial of John Eastman is ongoing. It is uncertain when a final decision will be rendered. But as far as his First Amendment defense is concerned, the result may already be clear based on how Judge Roland has framed the issue.

What did Eastman know and when did he know it?

Broadly speaking, the State Bar can discipline or disbar Eastman if it can either prove that he understood what he was saying and doing were false, or that he was grossly negligent in not knowing. If he so advised his clients and also made false public statements, his federal and state free speech defenses would fail under existing law.

Independently, the State Bar will prevail if it proves that (a) based on misinterpretations of historical sources and law review articles, Eastman knew or was grossly negligent in not knowing that his sources were fundamentally flawed, and (b) he provided, and proposed actions based on, legal advice regarding the unilateral authority of the Vice President to disregard or delay the counting of electoral votes that he knew, or was grossly negligent in not knowing, was contrary to and unsupported by the historical record and established legal authority and precedent, such that (c) no reasonable attorney with relevant expertise would have concluded that the Vice President was legally authorized to take the actions he proposed.

Whatever the outcome at the trial level, unless Eastman voluntarily resigns from the bar, appeals are almost certain to follow and another chapter in First Amendment law might well be written.

Tags