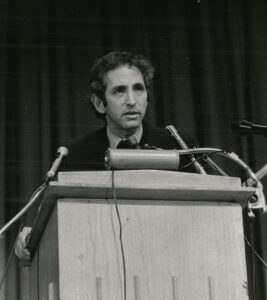

Daniel Ellsberg, the whistleblower best known for sharing the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times in 1971, who dedicated his life to protecting press freedoms and standing against prior restraints, died June 16 at 92 from pancreatic cancer.

Ellsberg authored multiple books, including: “Papers on the War” in 1971, “Risk, Ambiguity and Decision” in 2001, and “Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers” in 2002. In 2018, he was awarded Sweden’s Olof Palme Prize for “profound humanism and exceptional moral courage.”

Ellsberg was a consultant who had worked on the 7,000-page Department of Defense study dubbed the Pentagon Papers, which were classified documents analyzing U.S. decision-making before and during the conflict in Vietnam. Ellsberg was the first whistleblower to be indicted under the Espionage Act of 1917, but the charges against him were dismissed due to government misconduct, including a break-in at his psychiatrist’s office and illegal wiretaps.

Following Ellsberg’s leak of the papers to the New York Times and The Washington Post, the Nixon administration sought to stop publication.

A prior restraint is an order issued by a court that prohibits the publication or broadcast of material that in some way is deemed especially harmful. Prior restraints prevent material from ever reaching the public, a serious step that diminishes the marketplace of ideas and the well of information that informs citizens in a self-governing society.

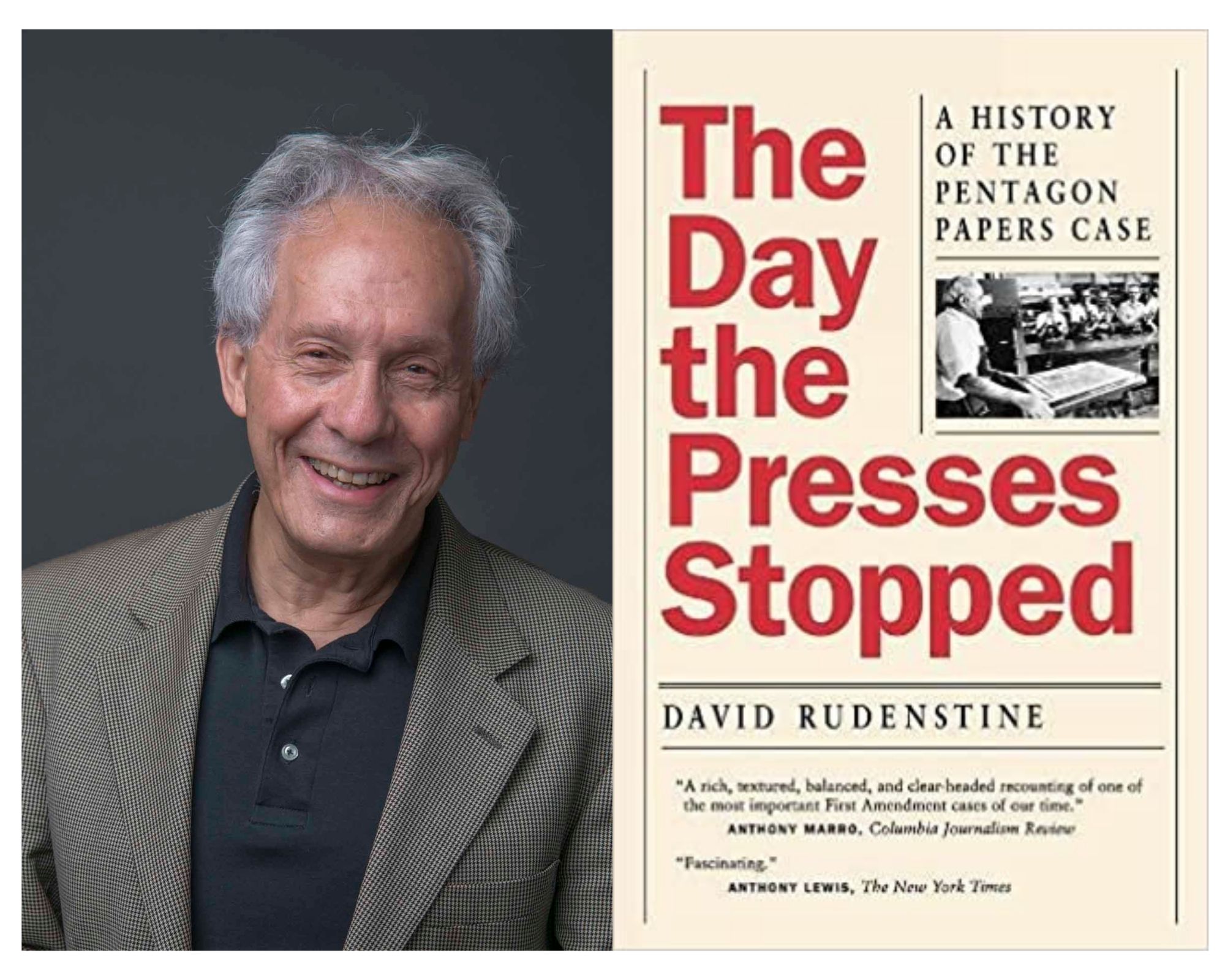

The most consequential of prior restraint cases was the one that resulted from Ellsberg’s leak of documents — New York Times Co. v. United States, widely known as the Pentagon Papers case.

A federal appeals court in Washington, D.C. upheld the right of The Washington Post to publish its stories on the Pentagon Papers, but the federal appeals court in New York issued an injunction against The New York Times. The two cases were combined at the Supreme Court. From beginning to end, the case sprinted to a decision in just 16 days, a mark of its importance since a newspaper had been stopped from publishing stories of enormous public interest.

The Supreme Court ruled 6-3 to lift the injunction against the Times. In a three-paragraph per curiam opinion, it said that any request for a prior restraint “comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity.” The government, the court said, had not met its burden of showing justification for a restraint on publication. The court did not articulate a test that the government would have to satisfy in order to stop publication, but Justice Potter Stewart in a concurring opinion stated that publication of information would have to “surely result in direct, immediate, and irreparable damage to our Nation and its people.” Federal courts have utilized Stewart’s test — an exceptionally difficult standard to meet — in later cases. Whether it is the government or a private party asking for a prior restraint, the focus is on the likelihood that publication would cause serious and imminent harm.

The decision upheld the First Amendment right of journalists — at least in the absence of imminent harm that would surely occur — to publish classified information that was in the public interest. The ruling affirmed that the role of the press in a democracy was to serve the governed, not the governors. Without Ellsberg’s contribution and commitment to transparency, press freedoms and protections wouldn’t be the same.

More from First Amendment Watch: