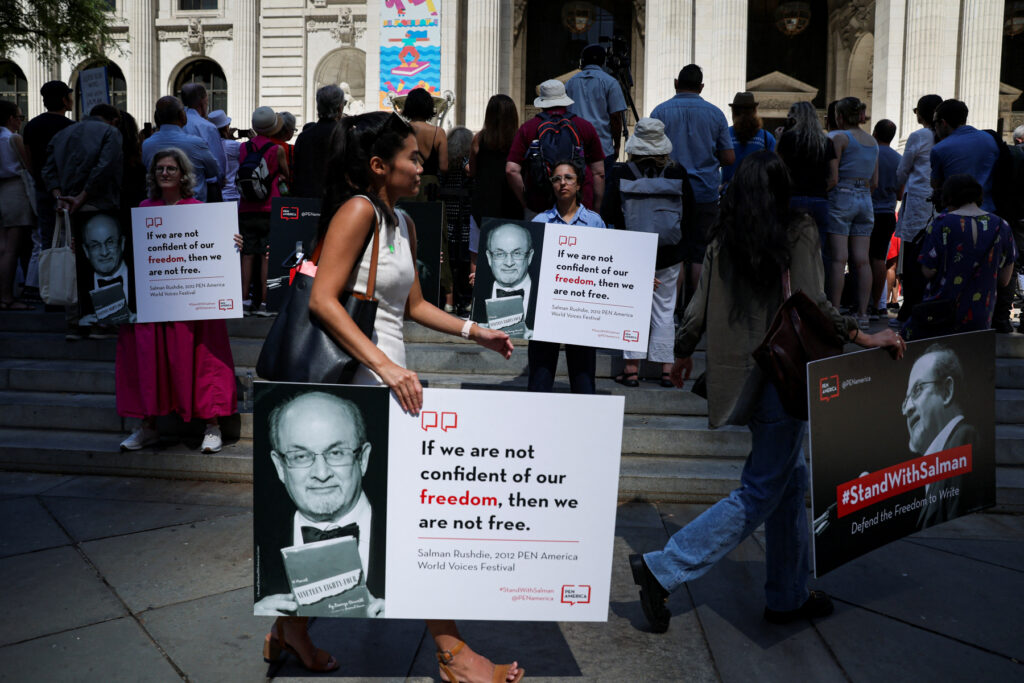

Jacob Mchangama is a Danish lawyer, FIRE Fellow and author of Free Speech: A History from Socrates to Social Media, published in March. First Amendment Watch asked Mchangama, a free speech historian and scholar, his perspective on the evolution of blasphemy laws and the context surrounding the vicious attack against Salman Rushdie, a Distinguished Writer in Residence at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute.

FAW: You point out in your opinion piece appearing in the New York Daily News, “The larger legacy of Rushdie’s Satanic Verses” that it’s been more than 30 years since Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued the fatwa against Salman Rushdie and the book’s publishers. It’s sobering that he had moved on from exile and fear only to experience serious injuries from an attack 33 years later. Does history provide a precedent for a way forward?

J.M.: I think the best way forward is to show solidarity and not to cave in to the Fanatic’s Veto. European Christians gradually got accustomed to ideas and portrayals that were once deemed worthy of capital punishment and I think that habituation has yet to take root in some Islamic communities unfortunately. In this fight, however, it is crucial that we ally with the many Muslims who pay a high price for speaking out against fundamentalists´ attempts to silence intra-Muslim heterodoxy and dispel the myth that this is only a Western concern.

FAW: To quote you in a January 2022 YouTube video: “No one can guarantee the outcome of giving a free, equal and instant voice to billions of people but a careful look at history suggests that for all its flaws, free speech makes the world more tolerant, democratic, free, innovative, and yes, even fun.” That’s a very hopeful, optimistic view. Through a historical lens, which time periods or events buttress your stance?

J.M.: The second half of the 18th century until the French Revolution spiraled out of control offers much promise. So does the second half of the 19th century where free speech and democracy gained ground. The third wave of democratization in the second half of the 20th century went hand in hand with great global gains in terms of securing free speech, and in 2011 a coalition of states at the U.N.– led by the U.S. – defeated a decade’s old attempt by Islamic states to ban blasphemy under international human rights law. Also blasphemy bans in European democracies like Denmark, Norway, Ireland and Iceland have been abolished in the past seven to eight years. These successful strategies should inform efforts going forward.

FAW: Are there episodes in the history of blasphemy which bring context to what happened to Professor Rushdie?

J.M.: It’s ironic that Persia – modern day Iran – was home to the most daring free thinkers of the medieval period and that these were actually Muslims. One of them being the Persian physician and philosopher Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyā al-Rāzī (known as Rhazes in the West) who lived from around 850 to around 925. For al-Rāzī, reason was “the ultimate authority, which should govern and not be governed; should control and not be controlled, should lead and not be led.” He was highly critical of the restrictions religious fanaticism placed on free thought: “If the people of [a given] religion are asked about the proof for the soundness of their religion, they flare up, get angry and spill the blood of whoever confronts them with this question. They forbid rational speculation, and strive to kill their adversaries. This is why truth became thoroughly silenced and concealed.”

So more than a 1,000 years ago al-Rāzī clearly condemned the sort of intolerance that the Iranian regime of the 21st century is based upon.

Well into the 19th century blasphemous libel was vigorously prosecuted in the U.K. Richard Carlile was a prolific blasphemer publishing and peddling Deist publications like Thomas Paine’s “The Age of Reason” to the lower classes, for which he spent some six years in prison. In October 1819, Carlile was tried for blasphemy and seditious libel, and the attorney general pulled no punches. He denounced “The Age of Reason” as “one of the most abominable, disgusting, and wicked attacks on religion and its author, that has ever appeared in the world.” But it was not God or religion that needed protection. It was the established order of the British class-based society. According to the attorney general, prosecuting Carlile was necessary for “protecting the lower and illiterate classes from having their faith sapped and their minds divested from those principles of morality, which are so powerfully inculcated by the Christian religion. . . . [W]hen such terrible productions… are put … into the hands of those who unlike the rich, the informed, and the powerful, are unable to draw distinctions between ingenious though mischievous arguments, and divine truth—the consequences are too frightful to be contemplated.”

FAW: As a historian, do you see the attack on Professor Rushdie as a casualty of the broader contemporary lens on the United States with our internal conflicts of demarcated red and blue states, disinformation campaigns, book bans and frequent mass shootings and attacks?

J.M.: No, not really. I think the attack on Rushdie was part of a global campaign by Islamists to silence “blasphemers” against Islam, that has led to death and destruction on many continents and with Islamic states and Muslims bearing the brunt of this onslaught against the right to think and speak freely.

FAW: From the New York Daily News opinion piece, you wrote: “Despite this bloody history, far too many people who take secular values and free speech for granted are unwilling to defend the very freedom that sets open democracies apart from theocratic states like Iran, or some of the other dozen or so Muslim-majority states that still formally punish blasphemy and apostasy with the death penalty.” What can each of us, as global citizens, do to defend the freedom of speech?

J.M.: Exercise it, show solidarity, be courageous and realize that we cannot take free speech for granted. This freedom has been hard won and we’re standing on the shoulders of intellectual giants and heroic champions who paved the way, often paying a very high price indeed.

Jacob Mchangama is a Danish lawyer, human rights advocate and author of “Free Speech: A History from Socrates to Social Media” (2022, Basic Books). Mchangama is a FIRE Fellow and the founder of Justitia, a Copenhagen-based think tank involved in human rights and free speech issues.

“Free Speech: A History from Socrates to Social Media”

Tags