By Azhar Majeed

Two police unions in Minnesota have advocated for a University of Minnesota student government leader to face punishment—both criminally and from within the university—for her anti-police comments.

If acted upon, the request would result in a violation of the First Amendment and, in all likelihood, considerable damage in the form of a chilling effect on student discourse.

In a late April meeting of the Minnesota Student Association, Executive Board member Lauren Meyers and other student leaders discussed a recent letter that the student government had sent to the university president. The letter called for the resignation of University of Minnesota Police Department (UMPD) chief Matt Clark. It alleged that Clark had “overseen and failed to act on the countless accusations of discrimination” during his time as UMPD chief, and that he had “failed to increase campus wellness and safety for students of color.”

As part of this conversation, Meyers stated that, with regard to the UMPD, students should “make their lives hell” and “annoy the s—- out of them.” Meyers expressed the goal of “us[ing] up their resources” and “mak[ing] their officers show up to something.”

Meyers’ statements arguably push the envelope of what is proper advocacy on the part of a student government leader, though reasonable minds can disagree on that. As a matter of First Amendment law, however, they are almost certainly protected speech. The comments do not rise to the level of incitement to imminent lawless behavior or any other recognized exception to the First Amendment.

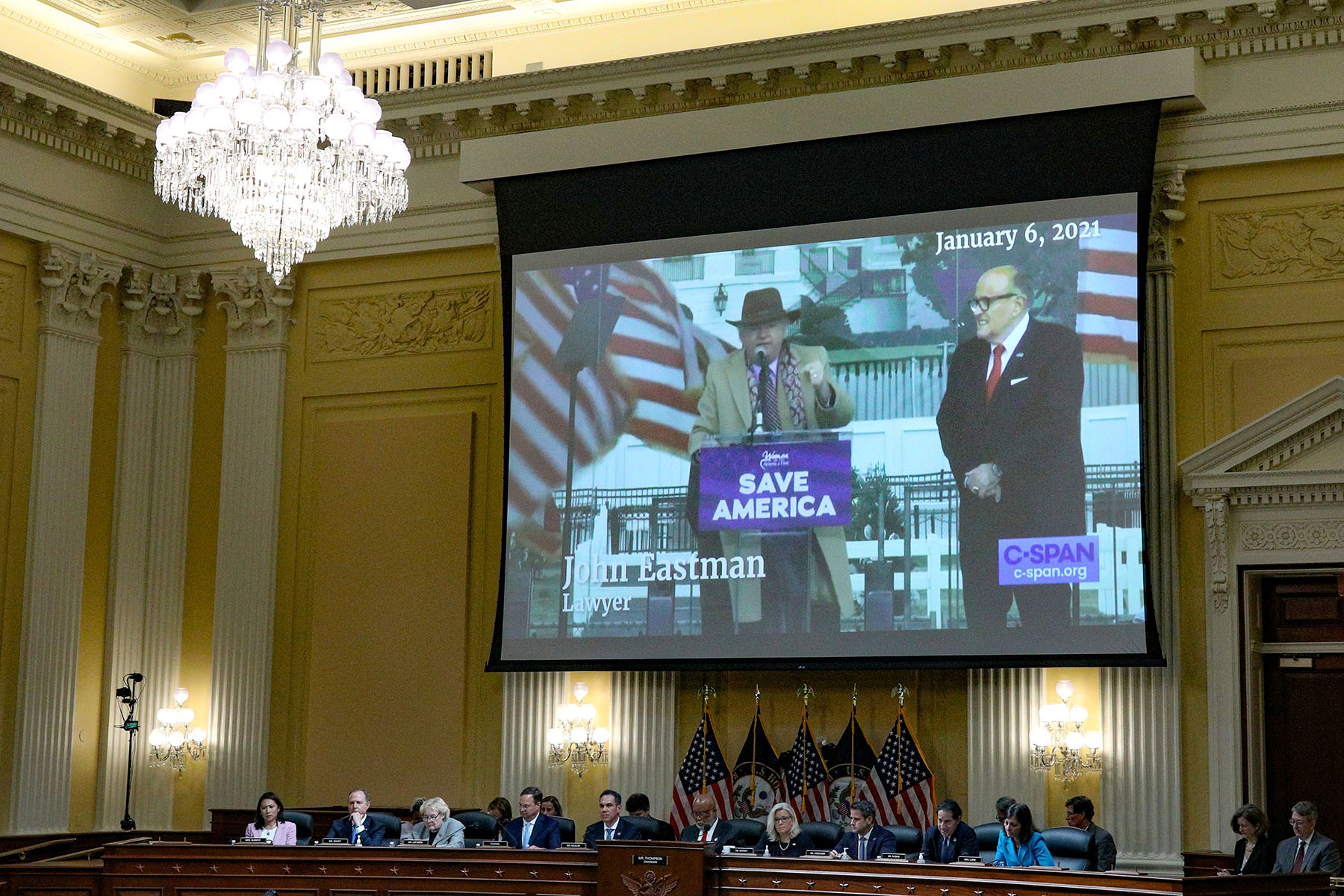

To constitute unlawful incitement, speech must be “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and must further be “likely to incite or produce such action,” based on the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969). (Notably, this exception to the First Amendment came up quite a bit earlier this year in discussions of whether then-President Donald Trump’s speech on January 6, preceding the attacks on the U.S. Capitol, constituted unlawful incitement and was thus not protected by the First Amendment.)

Yet the Minnesota Police and Peace Officers Association (MPPOA) and Law Enforcement Labor Services (LELS)—two unions representing police officers in the area—saw it differently. Skipping past the question of whether or not Meyers’ speech was protected, their recent joint statement takes issue with the underlying conduct that she advocates, and argues it will lead to many false reports by citizens.

The joint statement calls on the University of Minnesota to “initiate an investigation into this incident for Student Code of Conduct violations,” even referencing sections of the conduct code that the unions believe she may have violated, such as “Falsification” and “Disorderly Conduct.”

Moreover, the statement calls for an “outside agency [to] conduct a criminal investigation into this incident to determine if charges are warranted.”

Meyers’ comments are most reasonably read as general advocacy and, perhaps, hyperbole. They did not call for listeners to immediately take action against the UMPD, which would be necessary to meet the imminence requirement of the incitement doctrine. Nor was her speech—taking place in a student government meeting’s discussion about a recent letter—likely to result in such action.

In other words, Meyers’ comments could more accurately be characterized as generalized musings of what she would like to see happen.

The police unions’ failure to follow—or even to acknowledge—these distinctions is both unfortunate and at odds with their obligation to the First Amendment as public officials. The joint statement also sets a dangerous tone as to what will be considered acceptable or unacceptable discourse in the larger debates about policing, criminal justice reform, and the rights of those impacted by police misconduct. This is precisely the chilling effect that the First Amendment forbids.

To its credit, the University of Minnesota does not appear to have taken any action against the student, though it did respond to the initial controversy by stating, “These ideas are illegal and would directly conflict with ongoing efforts to keep our campus community safe.”

Again, the mere advocacy of “ideas”—including the ones espoused by Meyers—is protected speech, and a public university bound by the First Amendment ought to know better than to suggest otherwise.

This controversy will be one worth following.

Azhar Majeed is a free speech attorney and contributor to First Amendment Watch.

Tags