On July 8th, the U.S. Supreme Court received a petition to review a ruling issued by the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. The case involves a man claiming that five law enforcement officers violated his First Amendment right to record the police.

The case stems from an incident that occurred more than seven years ago. Levi Frasier was standing in a public parking lot in Denver, Colorado on August 14, 2014 when he spotted a group of police officers approach a silver car. Frasier saw officers interrogate the car’s owner, David Nelson Flores, pull him out of his car, push him to the ground, and punch him approximately six times in the head. Using his Samsung tablet, Frasier recorded the incident from about ten feet away.

After Flores was taken away, one of the officers approached Frasier and asked him to fill out a witness report. He then ordered Frasier to bring his tablet, and, over Frasier’sobjections, looked for the video. When the officer could not find it, he handed the tablet back to Frasier and let him go.

That year, Frasier sued the five officers for retaliating against him for exercising his First Amendment right to record. The officers argued that they were protected by qualified immunity because the right to record was not “clearly established law” in Colorado. A district court initially sided with Frasier on the grounds that the police officers had been told during their training that the First Amendment protected the right of citizens to record them in public. But in 2021, the Tenth Circuit reversed the lower court’s ruling, writing that “judicial decisions are the only valid interpretive source of the content of clearly established law” and that “whatever training the officers received concerning the First Amendment was irrelevant to the clearly-established-law inquiry.”

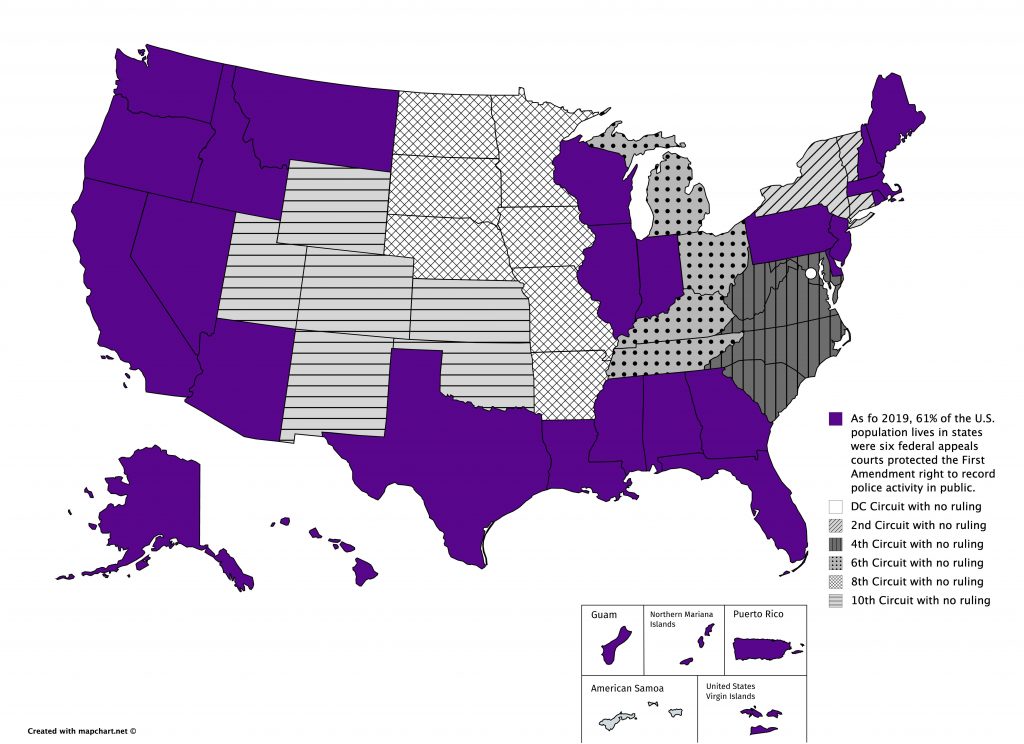

Despite numerous legal challenges over the right to record police officers in public, the Supreme Court has not yet ruled on the question of whether citizens have a First Amendment right to record the police. Because of this, only states in judicial districts that have established the right to record as a constitutional right consider it a “clearly established law.” (See map below). This lack of consensus has allowed officers that work in states without established laws to be able to claim qualified immunity from retaliation lawsuits.

In his petition, Frasier is asking the Supreme Court to state that it has been “clearly established” in all U.S. states since at least 2014 that the First Amendment protects the right of individuals to record police officers carrying out their duties in public.

Multiple First Amendment scholars, press advocacy groups, and news organizations have submitted amicus briefs on behalf of Frasier. Among those pushing for Supreme Court review is the Reporter’s Committee for Freedom of the Press which argues that the “lingering uncertainty that characterizes the right to record will continue to have a chilling effect on its exercise.”

“[T]he right the Tenth Circuit declined to recognize is of exceptional importance to the press and public, and its exercise depends critically on the deterrent effect of a meaningful damages remedy…[T]he circuits are in clear need of guidance about the proper approach to the qualified-immunity analysis when the right to gather information—as opposed to the right to speak or publish that information—is at issue. The gravity of the Tenth Circuit’s error, together with the chilling effect that disarray continues to have on the exercise of basic First Amendment rights, warrants review,” the brief states.

Tags