Symbolic speech as a form of protest, like taking a knee at a football game while others stand for the National Anthem, enjoys a long history in America. It’s been a powerful form of political expression going back to the protests in the colonies in the 1760s against British oppression. Various forms of symbolic expression—liberty trees, liberty poles, effigies of hated politicians, even the use of the number 45—brought multitudes into the political sphere and was critical in building opposition to British rule. Much of this symbolic expression was controversial and even offensive but a powerful form of protest then and now. – By Professor Stephen Solomon, Editor, First Amendment Watch.

See here for more on the question, Are NFL Players Protected By The First Amendment When They Engage In Political Protest On The Field?

_______________________________________________________________________________________

The Immense Power of Symbolic Speech

The founding generation did not have Twitter, Facebook, blogs, or broadcasting, but they did understand the power of symbolic expression to command attention and rally supporters.

When Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, imposing taxes on English subjects in the colonies, an outpouring of newspaper articles and pamphlets vociferously opposed the tax. That continued as additional laws raised the ire of colonists. Writers like James Otis, Jr., John Dickinson, and John Adams were well-educated lawyers and politicians, and many of their essays against Parliament’s laws defended the rights of the colonists by invoking English history as well as the country’s great constitutional documents like Magna Carta, the Petition of Right, and the English Bill of Rights.

The newspapers and pamphlets were effective in articulating legal arguments, but they had serious limitations. Many people in the colonies could not read, and even many who could read nevertheless lacked the education to fully grasp the arguments of sophisticated writers. Leaders of the opposition knew they needed a strategy to bring large numbers of people into the debate in order to show Parliament that there was widespread opposition to its measures. In other words, they had to find a way to democratize protest.

For the opposition leaders, symbolic speech proved the most effective strategy to make protest popular. Why? Symbolic expression involving liberty trees and effigies attracted huge crowds to the public square; in Boston, thousands came out in a town with a population of about 16,000.

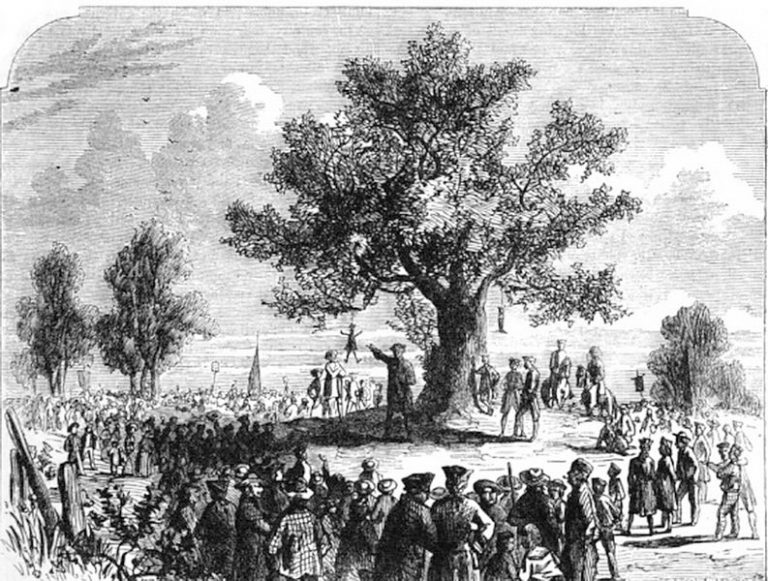

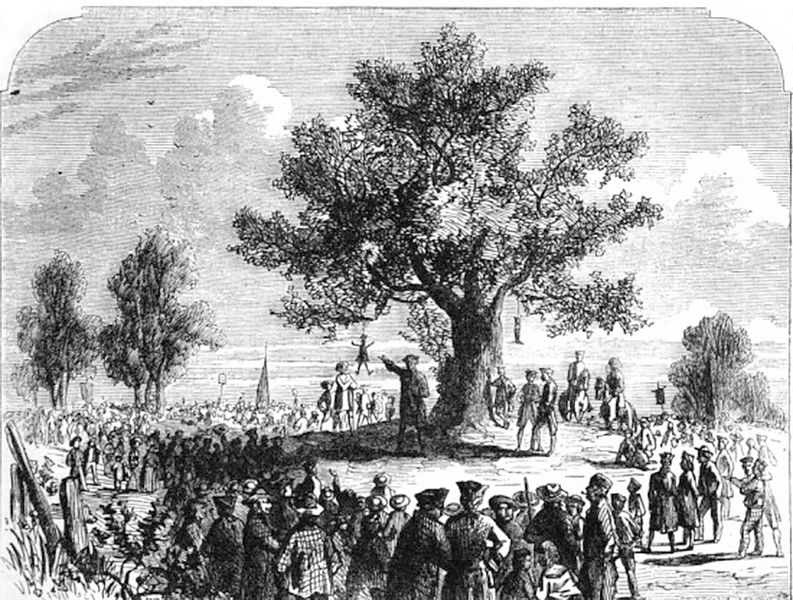

The Liberty Tree became the focus of protests against the Stamp Act with the hanging of effigies on August 14, 1765 (Houghton Library, Harvard University)

A liberty tree with effigies.

Symbols also brought immediate clarity to complex issues; people understood that an effigy of a British official hanging from a liberty tree represented the tyranny of a faraway Parliament even if they were not well versed in law and history. And symbols could have shock value similar to burning a flag or taking a knee today. Hanging effigies of hated officials along with an effigy of the devil, the representation of all evil in Puritan theology, was about the most scandalous thing a protestor could do in Boston.

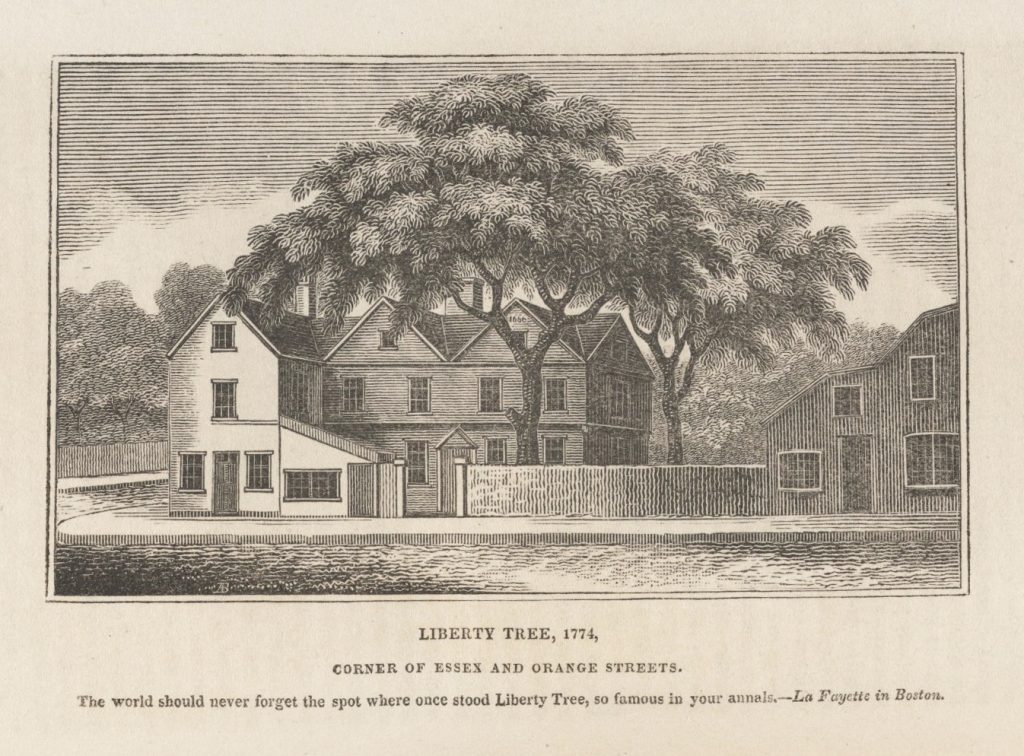

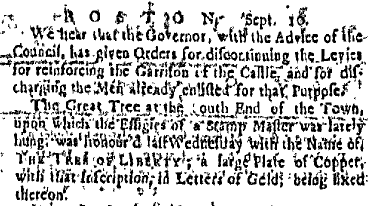

Symbolic protests against the British started in Boston on August 14, 1765, when a group called the Loyal Nine created a spectacle by hanging in effigy the local stamp distributor, Andrew Oliver, from a branch of the largest elm tree in town. Also hanging from the tree was a riding boot that everyone understood to represent the Earl of Bute, the former British prime minister whom the colonists thought responsible for passage of the Stamp Act. The boot was not empty—an effigy of the devil peered from the boot with a copy of the law. Thousands of people gathered at the tree throughout the day. A month later, the Boston Gazette reported that people had returned to the elm and fixed a plate of copper with letters of gold designating it as the Tree of Liberty.

The Boston Gazette (September 16, 1765) reports that the great elm has been named the Tree of Liberty.

This excerpt from Revolutionary Dissent: How the Founding Generation Created the Freedom of Speech (Stephen D. Solomon, 2016) discusses why Boston’s liberty tree was so effective as symbolic expression:

“For the patriots of Boston and elsewhere in 1765, the Liberty Tree became an inspiring image—so majestic and so ancient, reaching for the heavens in defiance of the arbitrary forces of nature. If the power of the king and Parliament counted as only slightly less than a force of nature, the Liberty Tree fortified the patriots’ resolve to oppose it when necessary. It became an important venue for political assembly, an open-air marketplace of ideas. It served as Liberty Hall, an outdoor meeting space to discuss colonial grievances and stage protests against the actions of royal authorities in the decade to come.

“Dedication of the Liberty Tree and its role as centerpiece of the gathering on August 14 showed how the universe of political expression was expanding. The tree, the boot, and the effigies expressed ideas in ways very different from the essays and letters and petitions that had dominated the debate until then. Unlike other forms of expression that involved words, either spoken or printed, the tree and the effigies were symbols. But they were speech nonetheless. The Loyal Nine and others who strung the effigies of the devil and the stamp distributor did so to communicate a profound disagreement with the taxes inflicted on them by England. Their use of symbols to express opposition to the new taxes involved a completely different mode of speech, but one that was ultimately as important as the essays discussing the constitutional rights of Englishmen.

“Symbolic speech, in fact, possessed some power that the written and spoken word did not. The essays and speeches against the Stamp Act used complex arguments that were foreign to many people’s understanding and experience, and even vigorous opponents of the tax sometimes disagreed among themselves on many of the arguments they were putting forward. But symbols stripped away the complexity of intellectual arguments and offered immediate clarity. For the people of Boston and elsewhere, Liberty Trees and effigies of stamp distributors stood for one big idea—the right to be free of arbitrary power, exercised in a legislative body far away without participation of the colonists’ own representatives.

“That fundamental idea of being ruled over by an oppressive regime was easily grasped by everyone who gathered at the tree, whether they had ever read a pamphlet or listened to an oration. In that way, the symbols could drive home complex arguments in a simple, unified way. As the relationship between the colonies and England deteriorated over the issue of taxes, the patriots in Boston and throughout the colonies increasingly recognized the power of symbolic speech to excite passions and define public debate. It was an age of large political questions that challenged the colonists at every turn. In the arsenal of persuasion, a Liberty Tree or a burning effigy reflected the exceedingly complicated issues of rebellion.

“Symbols possessed other vital attributes of effective political expression. Although they stood mute and passive, they brought immediate attention to themselves—the nectar that attracts the bees. Symbolic speech made protest popular, enabling active and visible opposition to the taxes to spread from the well-educated politicians and merchants to the community at large. The symbols employed by the Loyal Nine brought out thousands of people from Boston and surrounding towns, an essential element in the leaders’ goal of showing the depth of opposition to the Stamp Act. The symbols also called for a response by those who looked on. Rather than inviting people to listen passively to harangues against the Stamp Act, the Loyal Nine created an intriguing scene that invited participation.

“By their very nature, the symbols instigated even more speech. Everyone who came out to see the effigies of Oliver and the devil hanging silently from the tree couldn’t help but talk with those around them about what they saw and what it meant for the future. It was an impromptu town meeting with vast participation. And many of the gatherings transformed themselves into marches, as the leaders cut down the effigies and carried them at the head of parades that often went from one end of Boston to the other and then back again, through King Street, the commercial center of town, with stops at meaningful places such as the Liberty Tree, the town gallows, and important public buildings. . . .

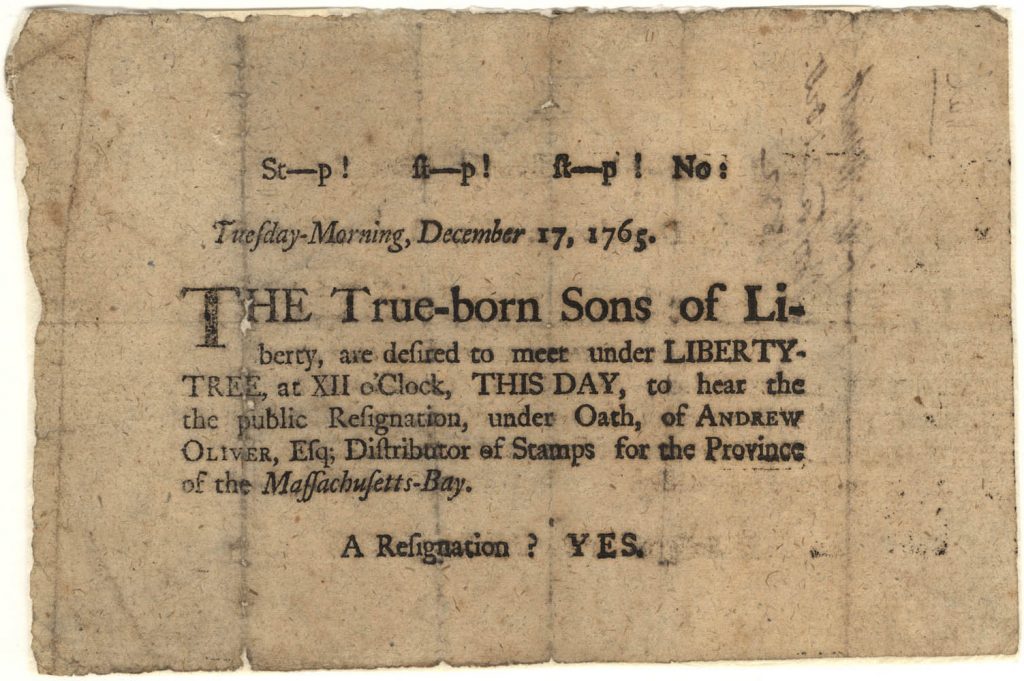

This broadside rallied people in Boston to the Liberty Tree on December 17, 1765 to witness the stamp distributor resign his office.

An Effective Form of Protest Spreads

Once colonial protestors found them effective, various forms of symbolic expression spread throughout the colonies. Liberty trees and poles sprouted almost everywhere. And use of the number “45” to represent martyrdom to freedom of the press spread with countless events in colonial towns.

The following is from Revolutionary Dissent: How the Founding Generation Created the Freedom of Speech (Stephen D. Solomon, 2016):

Liberty Trees and Liberty Poles

“After the great elm in Boston proved so effective in democratizing protest, Liberty Trees found fertile soil all over the colonies. In Newport, Rhode Island, William Read donated his buttonwood tree, and deeded a parcel of land he owned around it, to the local Sons of Liberty to use for gatherings and to stand as a “Monument of the spirited and noble Opposition made to the Stamp Act.” Other New England towns such as Norwich, Providence, and Cambridge dedicated trees of their own. John Adams came across a buttonwood tree in his hometown of Braintree in May 1766. “The Tree is well-set, well guarded, and has on it, an Inscription ‘The Tree of Liberty,’ and ‘cursed is he, who cutts this Tree.’” Adams added, with more than a hint that opposition to the Stamp Act was not unanimous, that he understood that “some Persons grumble and threaten to girdle it.” Farther south, Maryland adopted a tulip tree and Savannah an oak tree, the latter dedicated as people “drank toasts to their colleagues in Massachusetts.” In New York, the symbol went off in a homegrown direction as Whig leaders rejected the tree as a symbol and instead raised a tall mast to serve as a Liberty Pole, topped by a flag or vane. Everywhere people used their Liberty Trees and Liberty Poles as places to assemble to discuss politics and to hang effigies to show their displeasure.

“In 1770, British General Gage wrote from New York to his superiors in London after observing the outdoor meeting places. “It is now as common here to assemble on all occasions of public concern at the Liberty Pole and Coffee House as for the ancient Romans to repair to the Forum,” he said. “And orators harangue on all sides.”

The Number “45”

The number “45” became a symbol for freedom of the press with the arrest of John Wilkes, a Member of Parliament who had criticized the King in issue 45 of his journal, North Briton, in 1763. The Sons of Liberty in America used Wilkes and 45 to create martyrdom for Alexander McDougall, a New York merchant who was arrested and held in jail for seditious libel for criticizing the New York assembly in 1769 for agreeing to provision British troops in the town:

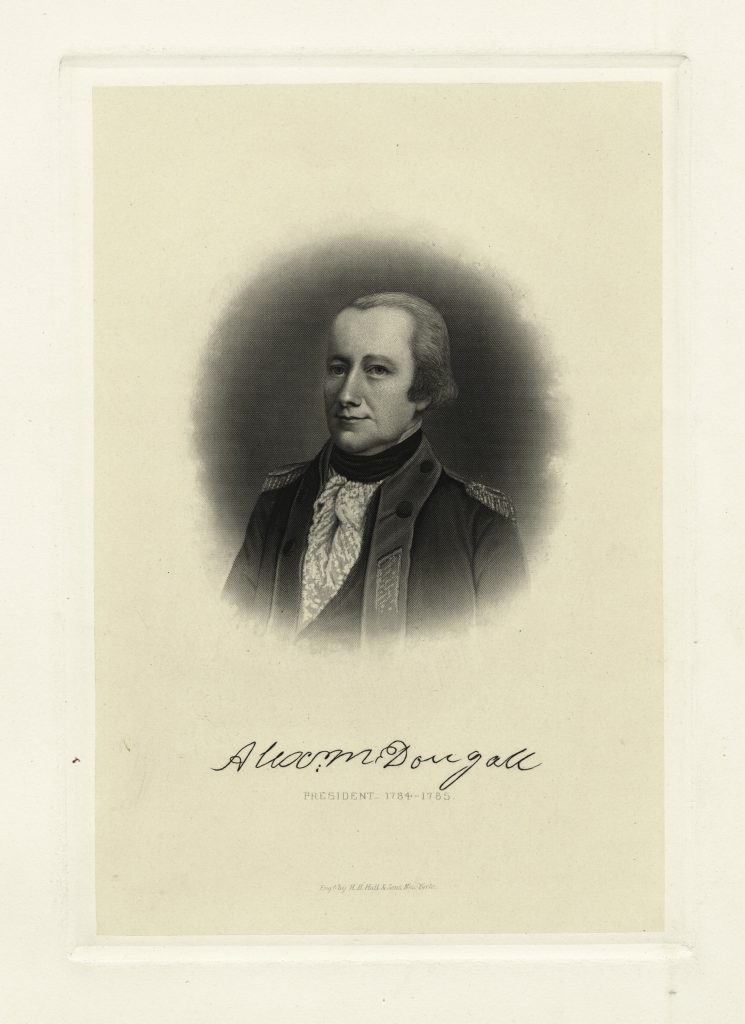

Alexander McDougall, jailed in New York in 1770, became a martyr to freedom of the press through use of the symbolic number “45.” (New York Public Library)an

“On the evening of March 14, 1770, a prison guard opened the door of Alexander McDougall’s jail cell so that visitors could enter. There were forty-five visitors, to be exact, and all of them were women. They could not fit into the tiny cell at the same time, so most of them spilled into the hallway outside waiting their turn. For publicity sake—and all of this was for publicity sake—the forty-five women had been described to the public as virgins. McDougall had been jailed for criticizing the royal governor and the New York General Assembly, and his supporters aimed to draw attention to him as a martyr for the cause of liberty. If the virgins were not enough to accomplish that, the number forty-five tied McDougall symbolically to John Wilkes, a member of Parliament who had gained renown for going to jail after criticizing the King in the forty-fifth issue of the newspaper he published.

“For a man confined to a damp cell in the city jail, it was an experience that was more enjoyable than any prisoner had a right to expect. McDougall proved to be a welcoming host, aided by the treats that his visitors brought with them. According to the New York Journal, his female callers “were introduced by a Gentleman of Note, to the Illustrious Prisoner, who entertained them with Tea, Cakes, Chocolate and Conversation adapted to the Company.” Then the women proceeded to sing the Forty-Fifth Psalm, an edited version that extolled McDougall and participatory democracy.

“In the coming days, as news of the virgins became the talk of the city, McDougall’s critics struck back. One of them, writing under the pseudonym Satiricus, made the mocking observation that “he that is courted in a gloomy Prison, by Forty-Five [virgins] in one Day cannot fail of being a MAN INDEED.” One wag made fun of the encounter by suggesting that each of the forty-five virgins was forty-five years old. . .

“The motivations of the Sons of Liberty in creating an American Wilkes were transparent to everyone. A few weeks after McDougall went to the New Gaol [jail], Lieutenant Governor Colden himself saw through the political theater in writing about McDougall. “He is a person of some fortune,” wrote Colden, “and could easily have found the Bail required of him, but he choose to go to Jail, and lyes there imitating Mr. Wilkes in everything he can.” McDougall’s opponents understood that his jailing could make him a martyr and inspire more dissent throughout the colonies. . . News of the events in New York did spread and elicit support. As a patriot in another colony said upon hearing of McDougall’s arrest, “The Gentleman’s Cause imprisoned at New York, is the Cause of the whole Continent; and from this Moment, I devote my Fortune and my Life, to secure him fair Play.” Another promised that many supporters from other provinces would attend the trial.

“To transform McDougall into the American Wilkes, the Sons of Liberty needed pageantry and political theater that went beyond the effigies and demonstrations they had employed to protest the Stamp Act. The key strategy was to associate McDougall with the magical number forty-five. The effort began immediately. Within a few days of his incarceration, a “true female friend to American Liberty” visited McDougall and gave him a cut of venison marked with the number forty-five. Meals provided creative opportunities to draw attention to him. On February 14, the forty-fifth day of the year and less than a week after McDougall went to jail, the New York Journal reported that “forty-five Gentlemen, real Enemies to internal Taxation . . . went in decent Procession to the New Gaol; and dined with him, on Forty-five Pounds of Beef Stakes, cut from a Bullock of forty-five Months old, and with a Number of other Friends, who joined them in the Afternoon, drank a Variety of Toasts, expressive not only of the most undissembled Loyalty, but of the warmest Attachment to Liberty . . . and the freedom of the Press.”

“In March, the fourth anniversary of repeal of the Stamp Act provided an opportunity for a big event and the attention that would come with it. Three hundred members of the Sons met for dinner. Before the food was served, the group nominated ten men to dine with McDougall in his cell, “where a suitable dinner was also provided.” After making forty-five toasts, including one to McDougall, the entire group walked to the New Gaol “with Music playing and Colours flying.” They gave three cheers to McDougall, who answered them with cheers of his own and then delivered “a short address” through the grates of his prison window. Then the crowd moved on to the Liberty Pole nearby, taking down the flag from the top and marching with it around town.”