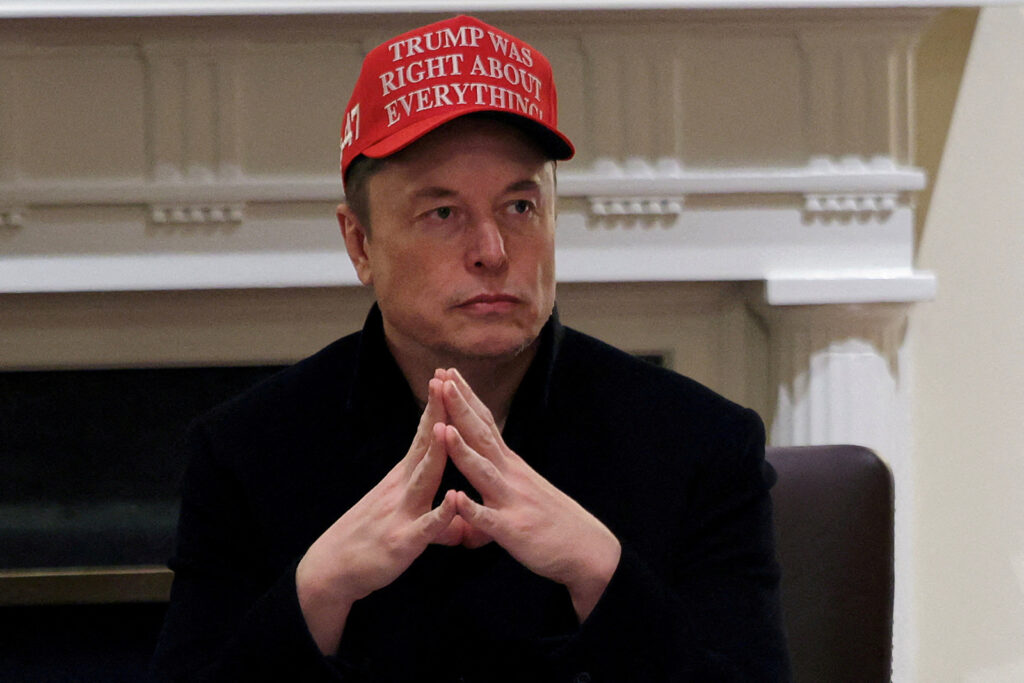

Last month, WIRED reporters exposed the identities of six engineers in Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, leading to a flurry of online chatter.

In one instance, an anonymous account on X reportedly encouraged users to “Doxx them,” further amplifying their identities. According to The New York Times, Musk replied “You have committed a crime.”

The next day, interim U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, Ed Martin, Jr., posted an image of a letter to Musk on X, in which he offers his legal services.

Dear @elon, Please see this important letter. We will not tolerate threats against DOGE workers or law-breaking by the disgruntled. All the best. Ed Martin pic.twitter.com/jIgMPVbPT5

— Ed Martin (@EagleEdMartin) February 3, 2025

“I ask that you utilize me and my staff to assist in protecting the DOGE work and DOGE workers,” Martin wrote. “Any threats, confrontations, or other actions in any way that impact their work may break numerous laws. Let me assure you of this: we will pursue any and all legal action against anyone who impedes your work or threatens your people.”

But on Feb. 4, nearly 50 civil rights and free speech organizations, including Freedom of the Press Foundation, signed onto a letter sent to Martin, expressing concerns over his posts on X and the First Amendment implications of any actions taken against WIRED reporters, requesting he “publicly commit to abide by the First Amendment.”

“Threatening to prosecute First Amendment speech and activity is not only at odds with the U.S. Constitution, it is also entirely inconsistent with Musk’s own stated principles and the right of the American people to know what the government is up to,” the letter stated. “Threatening to file frivolous charges against Americans and vaguely insinuating that wide swaths of constitutionally-protected speech and activity could invite criminal investigations and prosecutions may already violate these and other rules of professional conduct. Actually doing so almost certainly would.”

First Amendment Watch spoke with director of advocacy at Freedom of the Press Foundation, Seth Stern, about the First Amendment issues baked into the online exchange. Stern described Martin’s letter as intentionally ambiguous, argued that confusion over DOGE as a quasi-government agency brings its transparency responsibilities into question, and described the free speech issues that may arise from Musk’s roles as a social media platform owner and advisor to the president.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

FAW: Is DOGE a government-funded agency and is Elon Musk paid as a federal employee?

Stern: I don’t think anyone really knows exactly how DOGE is structured, and I think that that is somewhat intentional. It’s up in the air. But I think that for purposes of the First Amendment, I would submit that someone who is doing work on the government’s behalf, who has access to the public’s records and has been delegated by the president’s authority to make decisions about governance, you are dealing with a public official. And to the extent that ambiguities about whether they are or not part of the government would create problems in determining what their obligations are in terms of transparency. That is an indication that the entire thing is improper in the first place for DOGE to be doing the work it is doing. It should be subject to all of the transparency obligations that come along with being an agency of the government. If it’s not, it shouldn’t be doing that work.

Martin’s letter arises from an assumption that naming or reporting on DOGE agents or employees constitutes doxxing, harassment, concepts that you might apply to private citizens. Of course, nobody was doxxed, nobody listed these people’s home addresses. But putting that aside, the entire framework of Martin’s thinking is based on concepts that usually you would talk about in reference to private citizens. It’s absurd to suggest that government employees at the center of a public controversy cannot be identified or criticized. Martin’s letter and similar sentiments that Musk himself has expressed seem to take for granted the obligations that come with being a public servant, and the extent to which that relates to ambiguity about the exact status of DOGE employees, versus just an ignorance about the transparency obligations of public employees. But the whole thing seems to arise from a belief that DOGE’s people are not subject to the same standards as the rest of the government.

FAW: Is this threat directed towards the WIRED reporting that identified DOGE employees, or could this have been more of an umbrella-type threat towards all press or media covering the efficiency group?

Stern: I think it was intentionally ambiguous. The threat followed an exposé. Elon Musk responded with something to the effect of “You’ve committed a crime.” Pretty much immediately right after that, Martin fired off his first letter, essentially offering his services to Elon Musk to investigate alleged crimes. So taken in that context, it sure seems like the letter was premised on a belief that Musk was correct, that tweeting out the names of DOGE employees originally identified in the WIRED post would be a crime. He did not direct his threat of prosecution to WIRED journalists expressly, but if it is his belief that identifying those employees is criminal, then look, WIRED did that. No doubt about it. As did many people who posted about the WIRED article. Beyond that, it’s just quite disturbing to see a prosecutor offer up his services, and do so publicly. It’s disturbing to see — absent a pending investigation, absent any of the normal formalities that come along with an investigation — a prosecutor using a public platform to offer up their services to a particular individual. DOGE itself also has been credibly accused of illegality on several fronts, and might end up as a defendant at some point before Mr. Martin’s office. So for him to so expressly align himself with somebody so wealthy, somebody so political, somebody at the center of such a heated controversy, based on such frivolous accusations of wrongdoing, is the polar opposite of what you expect from an impartial prosecutor charged with upholding the Constitution and seeking justice apolitically. He phrased his letter, as inartful as it was, ambiguously enough that he could probably deny having specifically threatened WIRED journalists. But that doesn’t really resolve the concern. There are any number of levels of problematic-ness when it comes to that letter.