Since the beginning of the Israel-Hamas war on Oct. 7, colleges and universities across the country have been embroiled in conflict, with demonstrations from pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli groups bringing tensions on campus to new heights. Some school leaders have been accused of failing to adequately protect their students from bigotry, highlighting conflicts between free speech principles and university codes of conduct.

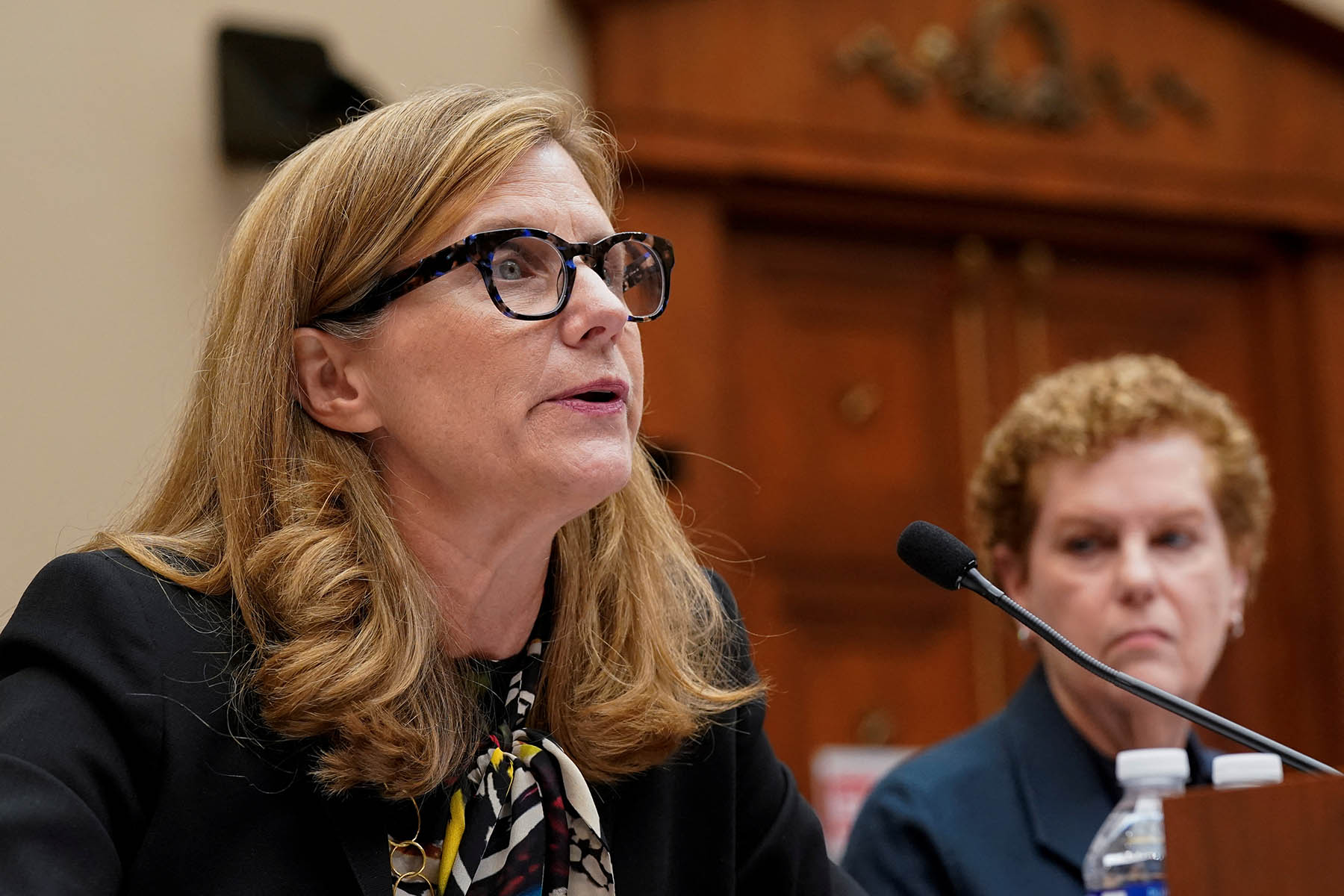

Following a December congressional hearing, the presidents of Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology faced national backlash over their testimonies, in which they did not unequivocally state whether calls for the genocide of Jews would violate their universities’ codes of conduct. UPenn President Liz Magill resigned days after her testimony. Harvard President Claudine Gay also ultimately resigned from her post, after the controversy brought increased scrutiny to her academic record and accusations of plagiarism.

In a January interview with First Amendment Watch, First Amendment expert Will Creeley, legal director at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), discussed the issues of law and ethics behind the controversy, outlined where the lines around protected speech on campus should be drawn, and argued that pushing unpopular or offensive speech underground could cause more harm than good.

(Editor’s Note: FIRE contributed some funding for a First Amendment Watch project in 2023. This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.)

FAW: Questions about the limits of free speech on college campuses have taken center stage in recent weeks. What was your reaction to their testimonies and why do you think the public reacted so strongly to it?

WC: I think that by the time the presidents were on Capitol Hill, in some ways, their ability to best answer that question regarding “calls for genocide” had already been compromised, given their checkered record on free expression and their failure to demonstrate an even-handed, viewpoint-neutral approach to protecting expressive rights. In other words, they were imperfect messengers. So while their answers were legally correct, they had lost credibility as leaders willing to uphold those definitions in practice. While legally correct, there’s an element of empathy and understanding; the truth is that students on campuses are freaked out, pro-Palestinian students, pro-Israeli students, and everyone in between are exhausted, horrified and frightened. So in answering questions fairly robotically, the fact that the presidents were insisting on the necessary nuance did not come through as a principled articulation, cognizant of the fraught moment on campus, but rather as a legalistic out. That was the real problem.

I think they would have been far better off recognizing the difficulties and challenges that students are facing, explaining that calls for genocide can indeed violate student codes of conduct but that to best protect expressive rights, as these campuses are committed to, the First Amendment and basic principles of free speech require an examination of the context of the speech. And that’s the most fair and exacting way to ensure that we protect the broadest range of free expression on campus, while also ensuring that true threats, discriminatory harassment, incitement to violence, and other unprotected speech is punished. In other words, they needed to read the room. I will say that anytime an elected official is asking you a question, and there appears to be only one acceptable answer, we should all be nervous. It’s not a good place to be. Congressional hearings are where nuance goes to die, right? If we insist that there are some magic words that are automatically denied constitutional protection, we’ve already forgotten the power and promise of the First Amendment. There are no words that are so awful, they can’t be reexamined, reclaimed, repurposed, debated, discussed, or simply ignored. But the insistence by Rep. Elise Stefanik that the presidents commit ahead of time to a vague and viewpoint discriminatory ban on “calls for genocide” is sharply at odds with both the First Amendment and basic principles of free speech.