Anthony Comstock is perhaps best known to most historians as a devout Christian man who waged a decades-long campaign against the distribution of what he considered “obscene” or “lustful” materials in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But his name is making headlines today, due in part to legislation being passed nationwide that limits abortion access, bans books in schools and threatens to prosecute librarians.

Anthony Comstock, New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, 1899. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

For more than 40 years, Comstock worked to rid literature or other forms of written expression of obscenity. In 1873, Comstock founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which sought to “supervise public morality in the state, bring offenders to justice, and advocate for stricter legislation against immoral conduct,” according to Library of Congress records. Comstock then successfully lobbied for the Comstock Act of 1873, which banned the mailing and receiving of “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” writings, such as books or pamphlets, or “any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring an abortion.” Comstock was appointed as a special agent for the U.S. postal service to enforce the law, which he did until 1907 before he died in 1915.

The Comstock Act has never fully been repealed, but ever-changing case law has made it obsolete. While some abortion activists worry of its application in a post-Dobbs world, the free speech implications of the act no longer apply due to First Amendment jurisprudence, such as unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination, that was not clearly established at the time of the law’s enactment.

Now, critics say, legislation across the country is mirroring those restrictions.

PEN America, an advocacy organization founded in 1922 that champions freedom of expression, issued a report in September analyzing book bans during the 2022-23 school year, and found that bans occurred in 153 school districts across 33 states. The bans, according to the report, “overwhelmingly” affected books focused on race, gender and sexual orientation. Books with themes of physical abuse, health and wellbeing, and grief and death were also strongly represented among those banned.

In addition to book bans, a wave of legislation often found in Republican-led states is threatening the prosecution of librarians who distribute obscene materials, similar to the Comstock Era punishments for those engaged in “lustful” behavior or possession of obscene material. According to the Washington Post, there are at least 17 states that are considering laws that strip protections for librarians from prosecution for the distribution of “harmful” or “obscene” content. Conviction under these laws can bring steep monetary fines and potentially even jail time, like a law in Arkansas signed last year that was temporarily blocked. Similar legislation has been signed in Indiana, Missouri, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

First Amendment Watch spoke with Amy Werbel, art history professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology and author of “Lust on Trial: Censorship and the Rise of American Obscenity in the Age of Anthony Comstock.” Werbel described the parallels between Comstock’s crackdown on obscenity and modern-day censorship. She expressed concerns over the threats of librarian prosecution, the importance of children’s access to reading materials, and warned of the potential impacts of such legislation on civil liberties.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

FAW: Is history repeating itself? Do you think the bills introduced in the past few years targeting “obscenity” or “lust” take after the Comstock Act of 1873? What are the similarities and differences?

AW: Yeah, they are, and I would say they’re also doing so with the same mix of political opportunism and genuine spiritual, evangelical mission, but I don’t say that everyone is sort of acting in a crass political way just to get donations and votes. But many of the politicians are, who are supporting them. These are just culture war issues that they can use to activate a certain percentage of their electorate and especially in gerrymandered districts this can be effective political campaigning, as it was in the 19th century. But there are people who also, like for Comstock, this is their evangelical belief. And what I would say to them is that I respect your right to your own beliefs. I believe they are protected under the First Amendment, as are mine, and they have to kind of stay in their lane for our diverse, pluralistic democratic experiment to thrive.

Some people think lust is great. That’s why I wrote the book “Lust on Trial.” That was the idea. If you could get rid of lust, you could get rid of sex beyond its prescribed purpose for reproduction within marriage. That’s the whole basis of Comstock ideology and that of its supporters, which is why they didn’t want birth control because birth control means that you can have sex without consequences. It’s kind of a terrifying turn of events that we’re even talking about the Comstock laws as relevant and yet here we are. So I would urge everyone to take seriously that this project is a danger to the civil liberties most of us take for granted. They need to be protected, and defended, and amplified, and cherished and negotiated in every generation.

FAW: In an opinion piece for The Hill, co authored with Jonathan Friedman of PEN America, you wrote that the Comstock Era is a “cautionary tale in today’s climate of book bans and educational censorship.” What did you mean by that? How is this story relevant today?

AW: I would say for those of us who are opposed to book bans and really take seriously that we are a pluralistic, diverse democratic society, the cautionary tale is that these kinds of efforts of censorship really do have a negative impact on our communities. We do have a very vibrant society with people who have many different religious beliefs, many different versions of gender orientation and sexual orientation, and many different attitudes toward every type of issue you could imagine, and having a thriving vibrant press enables everyone to be informed and educated and see things from many points of view. So there’s that side of the cautionary tale, which is that censorship, including book bans, is damaging to the free exchange of ideas which enables all of us to be our best selves. The other cautionary tale is that they tend, if you look at history, to really have a backlash that is much more profound than the power they’re able to exert. And I would say a really interesting example of what’s going on now is to look at the dramatic increase in religious affiliation. Most of these book bans are sponsored by religious zealots who are trying to impose their own kind of faith-based take on “what is morality” and “what is decency” on everyone else. In the late 19th century and early 20th centuries, this view of religion as a policing initiative really played a part in the diminished number of Americans who were interested in taking part in these orthodox religious denominations, and we’re seeing the same thing happen today. So this crusade alienates people who might be interested to join in the future, and especially young people. So I do think that these kinds of campaigns are self-defeating in the long run. In the short run, they’re very damaging. In the long run, it’s not the best way to win hearts and minds.

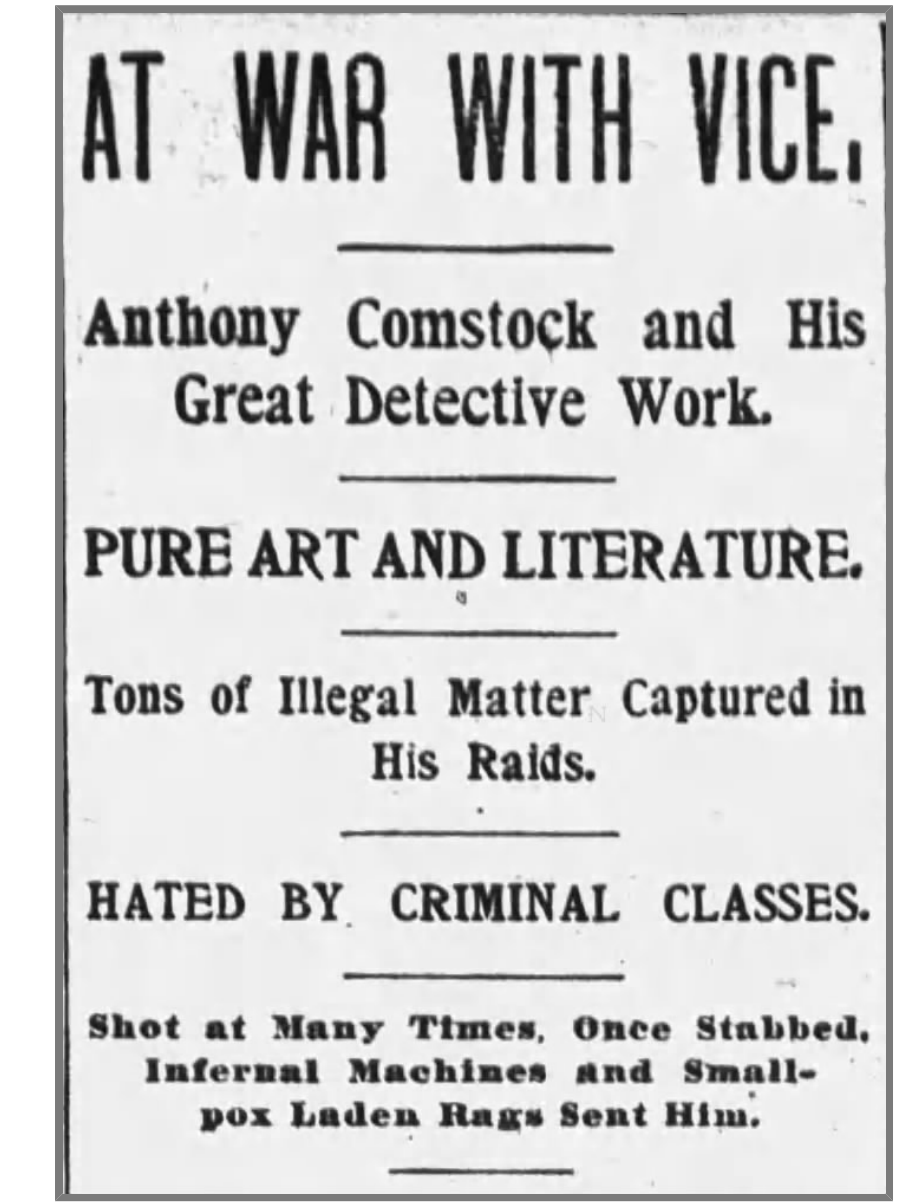

Sunday News (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania) · 13 Jan 1895, Sun. Copyright © 2018 Newspapers.com. All Rights Reserved.

FAW: Do you see parallels between the arrests of those engaging with “obscene” materials in the late 19th century under Comstock’s influence and the threatened prosecution of librarians in more than 15 states for the distribution of books deemed harmful?

AW: It’s easy to pass those laws, it’s easy to pass those resolutions, but if they actually enforced them, Americans are not going to be impressed by the sight of librarians prosecuted and hauled off to detention facilities. These laws are maybe popular in the short term when they’re preaching to the choir. But when they’re actually enacted and enforced, that’s when the rubber hits the road, and Americans start to realize that this isn’t what they had in mind when they think about what it means to be a citizen in the United States. Librarians are really popular. Libraries are really popular. Most of us grew up having our early literacy shaped and formed by having access to a couple of libraries. I think it’s one of the things that really makes the United States an exceptional nation. When you go around the world, it’s very rare to see a civil society that is so bolstered by a vibrant public library system. So again, I think it’s very easy for people to write this language, or copy and paste this language as distributed by conservatives or activists. But if they actually manage to start enforcing these actions it’s going to diminish the support that they have. That’s my prediction based on the historical example of Comstock. His real rise to power was before he was on the radar, when he’s just passing legislation in the halls of the New York State Legislature or even Congress. It’s when he started actively bringing indictments, based on these laws that he’s passed, that Americans started to really react and respond. Many Americans couldn’t read through the text of the First, Fourth and Fifth Amendments, but they feel as though those are their rights. And one thing that’s been really interesting to me in watching the protests on my own campus is our students actively talking about the First Amendment. I haven’t seen that really in my teaching career, until the time when they feel as though they should have the right to protest and then they’re going back and it’s like, why did they feel that way? Oh, yeah. Because of the First Amendment, they grew up with that kind of assumption. My prediction is that there will be a crescendo to these laws and school book bans that hopefully will be met by the same kind of resistance that Americans have brought in these kinds of campaigns in the past.

FAW: The Supreme Court’s development of First Amendment free speech and press protections took place very long after the Comstock Era. Are the First Amendment principles in force today enough to deal with the current various censorship initiatives?

AW: Just to clarify that, even though it is true that the jurisprudence that expanded civil liberties under the First Amendment happened after the Comstock era, but the point I make in my book is that the lawyers who defended all of the many, many targets of Comstock prosecution really cut their teeth and and honed their understanding of the legal principles and processes and procedures that support the First Amendment. So for example, these lawyers force judges to allow juries to see the evidence in the case when Comstock is saying that it’s too harmful for them, but the court establishes that for due process to happen, the jury needs to be able to see the matter to judge themselves whether it’s obscene. It’s the kind of thing where we have the foundation for that expansion of First Amendment civil liberties. So Comstock plays a role in the expansion of First Amendment civil liberties by stimulating backlash. Attorneys are instrumental for that rise, like Clarence Darrow, who gets his start representing people that Comstock prosecuted. So there’s a very sort of direct line there. Theodore Schroeder collected the files of defense attorneys who went up against Comstock and wrote the first textbook about defending clients in obscenity prosecutions. So I would say that Comstock played an important part of the 20th century expansion of speech rights, even though he’s dead. The people who live on after him who started their career in battling “Comstock-ery,” continue to do so.

[As for book bans], you do see students and parents rising up to discuss the harm to their families when books are declared “indecent” because they talk, for example, about same-sex parents or deny access to books about topics that students are curious about or have a need to understand. For example, sexuality. The one thing I’ve said many times before is that it’s not as though if you ban books about sexuality that you’re going to stop kids from having sex. They’re just going to do so with less information and appreciation for different perspectives and points of view.

FAW: Can you explain the comparisons between the censorship pushed by Comstock and the newfound efforts of censorship — like the limiting of access to books and teachings focused on the LGBTQ+ community or those with sexual content; abortion pill access; and the banning of drag performances and reading events? Are these measures, seemingly related to defending a religious ideology, similar to that of Comstock?

AW: I think the reason is, for me, it’s really easy to see all those things as the same thing is because in the era of Anthony Comstock, they were all lumped together as “obscenity” and they were all viewed through a very sectarian prism of an extreme orthodox view of Christian evangelicalism, in which the word of the Bible was the word of God. And the job of police enforcement in that view was to make sure that the word of God was the law of the land. Comstock wasn’t out there policing on behalf of the government of the United States. He was out there policing on behalf of Christ. He talked about himself as a soldier of Christ. And the people who backed him very much agreed with that cause. I think you see many of the people out there who are leading these charges for book bans and abortion bans are in the same vein. And so I think we should all be really concerned because “If you think, “Oh, it’s just this book or that book. That’s not so bad.” They’re not going to stop there. They never have and they never will. It’s all of a piece. It goes together in terms of who gets to decide what is obscenity, and obscenity is not protected under the First Amendment. But who makes that decision? Is birth control obscenity? Because it was under the Comstock laws. Are atheist or agnostic tracts obscenity? Because they were in the era of active enforcement of the Comstock laws. So I think that people should really be aware of the slippery slope of enabling Christian nationalists to start being the deciders about what we vibrant, pluralistic, diverse Americans have access to.

More on First Amendment Watch: