A lawsuit filed in federal court March 31 by a former Nebraska public high school newspaper reporter and a high school press association claims the shutdown of a student newspaper violated the First Amendment.

Former Grand Island Northwest High School student reporter, Marcus Pennell, and the Nebraska High School Press Association sued the Grand Island Northwest Public School District, and its superintendent for “unconstitutionally” terminating the school’s award-winning student newspaper, the Viking Saga, because it disliked an issue that included articles focused on “LGBTQ+ topics,” according to the lawsuit.

The complaint, filed by the American Civil Liberties Union, (ACLU), of Nebraska in the U.S. District Court for the District of Nebraska, claims the district and its superintendent, Jeffrey Edwards, “engaged in unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination and retaliation by terminating the newspaper class and the Viking Saga because of the viewpoint of Plaintiff student’s speech,” the suit states.

The Viking Saga has been in circulation since 1968. Each academic year, the paper publishes eight issues, and students enrolled in the class receive course credit. But in the summer of 2022 following its final issue of the academic year, the newspaper production class and the newspaper were shut down by school administrators.

Jane Seu, ACLU of Nebraska’s legal and policy counsel, said it is a “foundational principle” for students to maintain First Amendment rights at school, and while schools can sometimes censor speech in certain contexts, “we just don’t think that was appropriately exercised here because it was a discriminatory action. It was retaliatory in nature, and those kinds of actions have constitutional implications. We’re seeking to defend those students’ rights, Marcus’ rights, to free speech.”

According to the lawsuit, members of the district’s board of education voiced concern over three articles featured in the Saga’s June edition: An editorial written by Pennell about Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill; an opinion column titled “Science of Gender;” and a news article about the history of Pride Month. The June edition of the Saga was published on May 16, 2022.

The lawsuit claims that the three LGBTQ+-focused pieces sparked the shutdown, according to internal emails between school administrators and board of education members obtained by the ACLU in a public records request.

“Has anyone read our school paper this month?” wrote Paul Mader, a member of the district’s board of education, in an email to the five other board members on May 17, 2022. The email included three attachments, each a photo of the LGBTQ+ content in the Saga’s June edition.

A couple of hours later, Board of Education President Dan Leiser sent an email to high school Principal Paul Smith and the high school’s activities director, Matt Fritsche, denouncing the latest Viking Saga issue.

“I’ve read the publications in the Viking Saga. I’m sure this is a revenge tactic from the pronoun thing a month or so ago. But I’m going back and forth in the field and I just keep getting more and more upset,” the email stated in part. “I’m hot on this one, because it’s not ok. The national media does the same crap and I’ve had enough of it. No more school paper, in my opinion. You give someone an inch, they take a mile.”

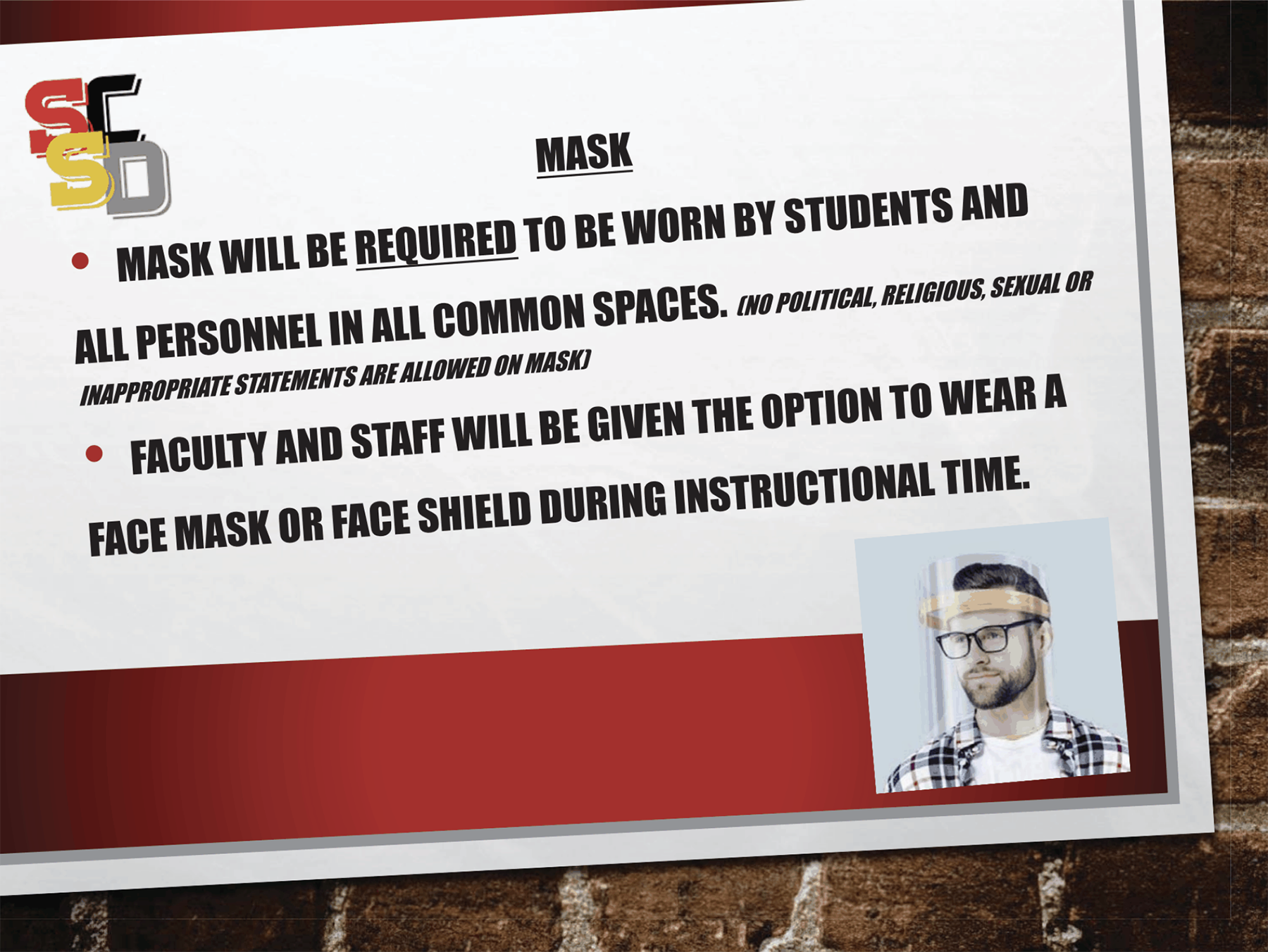

The “pronoun thing” Leiser referenced took place in March 2022, when then Principal Tim Krupicka told the newspaper class they were not allowed to use their chosen names and pronouns in their bylines, according to the lawsuit. Krupicka told the students this decision was made pursuant to a district policy about “controversial topics.” But when Pennell and other students questioned Krupicka, he said it was because “research was being done on both sides of the issue,” the lawsuit states.

Pennell, a transgender student, said when the newspaper class was informed of the pronoun and name usage policy that “it was just a lot of shocked silence.”

“We didn’t really try to protest it that much in those moments. We were all just so stunned by what was happening,” he told First Amendment Watch.

In the 1988 Supreme Court decision in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, the court held in a 5-3 decision that a principal didn’t violate students’ First Amendment rights for removing two articles from the school’s newspaper that focused on divorce and teen pregnancy. The court sided with the principal on the grounds that the school could restrict school-sponsored speech, including newspapers and plays, so long as the decision was motivated by “legitimate pedagogical concerns.”

A “pedagogical” concern is considered to be one focused on educational material or something that runs afoul of curriculums. This concern in Hazelwood was that the two articles about divorce and teen pregnancy didn’t meet the standards of the journalism curriculum. In the Viking Saga case, a “pedagogical” concern would be if the paper were poorly written, but according to Nebraska Press Association attorney Max Kautsch, that was not the case.

“[The district does] not have any rational basis reasons to terminate the curriculum,” he said. “It’s all about content, and we can’t have viewpoint discrimination in this country, even in high school.”

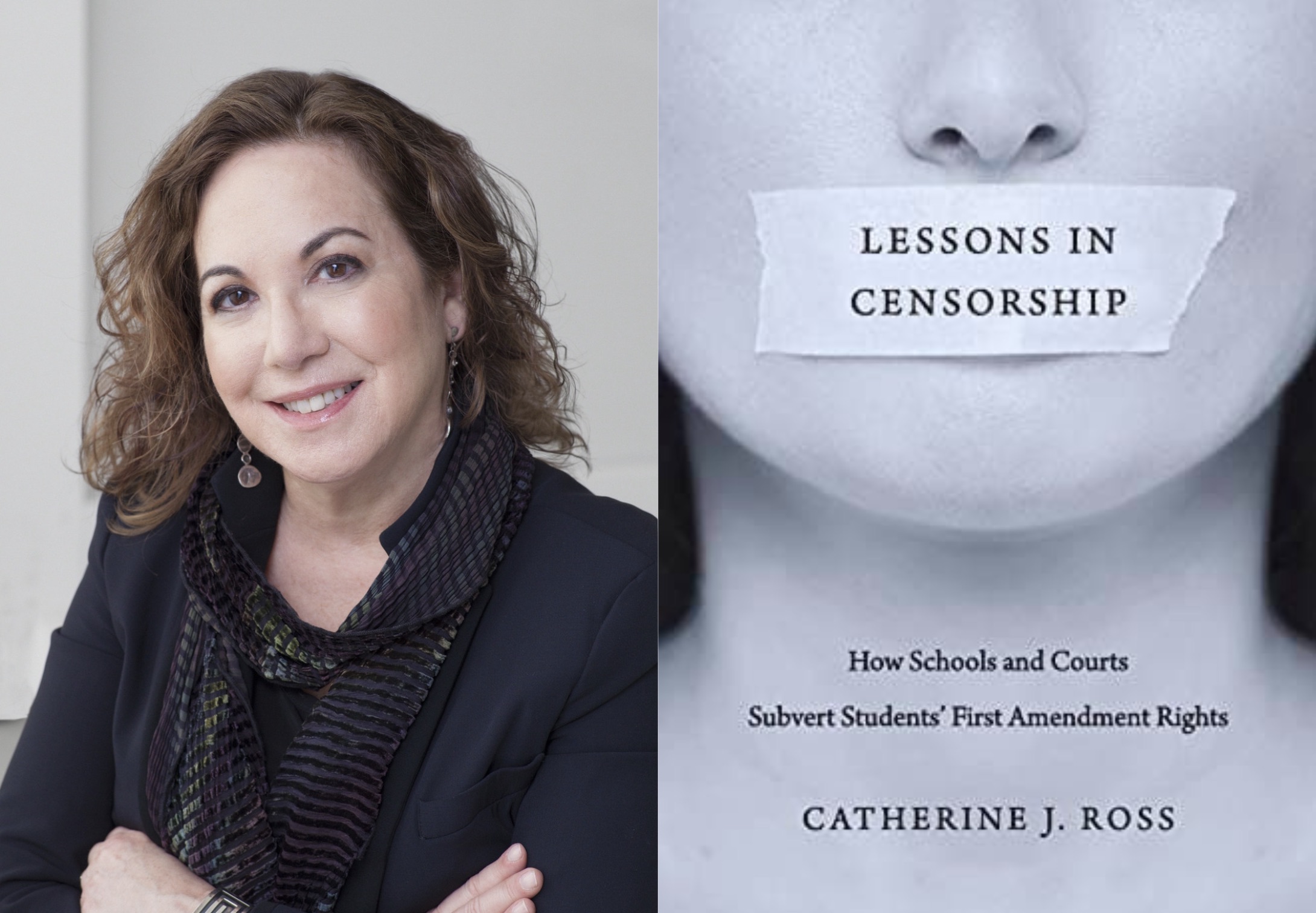

But because of Hazelwood, which Kautsch describes as a “blight on our constitutional jurisprudence,” school administrators have a “wide range of acceptable behavior” when it comes to censoring student speech, he said.

The 1969 Supreme Court decision in Tinker v. Des Moines, a landmark precedent for public school student First Amendment protections, limited a school’s ability to censor students unless the school is able to prove that the students’ speech would lead to a “substantial disruption.”

But the Supreme Court noted that students wearing black armbands to protest the Vietnam war in Tinker was protected expression as it wasn’t disruptive and the students paid for their armbands, whereas in Hazelwood, the students’ speech was in a newspaper which received school funding.

“The standard for determining when a school may punish student expression that happens to occur on school premises is not the standard for determining when a school may refuse to lend its name and resources to the dissemination of student expression,” wrote Justice Byron White for the majority opinion in Hazelwood.

Mike Hiestand, senior legal counsel at the Student Press Law Center, said that even though Hazelwood “does give school officials a fair share of leeway when it comes to censoring student media, one of the things they cannot do is censor based on viewpoint. That is pretty clearly what they did in this case.”

Included in the lawsuit is a letter sent by Superintendent Edwards to parents and guardians of the district in August 2022, which states that the Saga was not shut down for its LGBTQ+ content, but because of “many variables,” like “staffing support, student interest [and] class scheduling.”

Lindsie Rank, student press counsel at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, said that when a student publication is established, it creates “an open forum for student expression. But when you have that public forum for student expression, that doesn’t mean they have to have that forum open forever.”

The argument that student interest is low and that the school didn’t have the staff to support the paper’s production, Rank said, would safeguard the school from having to provide a “pedagogical concern” as required by Hazelwood because “they’re arguing it wasn’t even based on the content it was just based on logistical concerns.”

“The school could have stopped paying for or sponsoring the student newspaper just because of logistical concerns,” she said. “But what it can’t do is say that we’re doing this because of logistical concerns when it’s really clear from the evidence that logistical concerns were not their motivating factor.”

Seventeen states across the country have adopted “New Voices” legislation as of April 2023, which stem from a “student-powered nonpartisan grassroots movement” that seeks to counteract the student press rights offered under Hazelwood with more protective state laws. But Nebraska has yet to pass this type of legislation, and therefore Nebraska public high school students are still subjected to the “wishy-washy” protections offered by Hazelwood, Hiestand said.

Pennell, now a first-year student at the University of Nebraska Omaha, said in an ACLU press release that it was difficult to describe how he felt when the Viking Saga was shut down.

“I was crushed. Ever since I graduated, I felt I had a responsibility to seek accountability and advocate for the students who are still there, especially the LGBTQ+ kids,” he said. “We have a right to be who we are and to write about our lives. I am hopeful that censorship is not the end of this story.”

Tags