The Supreme Court heard oral arguments on Wednesday in Vidal v. Elster, a dispute that pits the First Amendment right to free speech against federal trademark law.

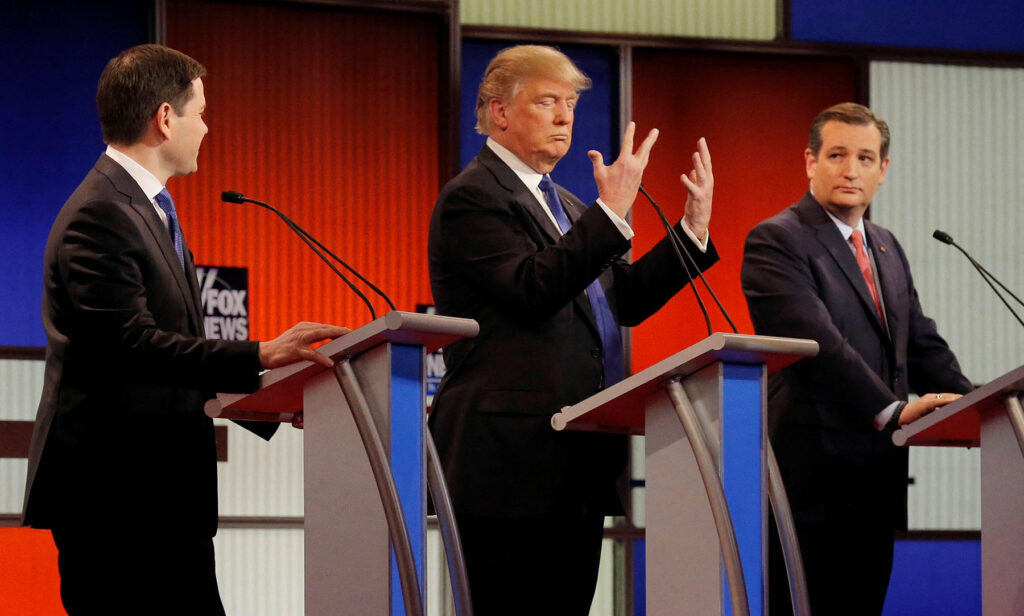

California attorney Steve Elster requested to trademark the phrase “Trump too small,” an insult derived from comments made by Florida Senator Marco Rubio during the 2016 presidential campaign, in which he said then-candidate Trump had “small hands … And you know what they say about guys with small hands.”

Elster wanted to print the phrase on T-shirts alongside criticism of Trump’s positions on certain public issues. For example, “Trump’s package is too small” on the environment, on civil rights, on LGBTQ rights, among other things.

The Patent and Trademark Office rejected Elster’s request, citing Section 1052(c) of the Lanham Act, the federal law prohibiting federal registration of any trademark that “[c]onsists of or comprises a name … identifying a particular living individual except by his written consent.”

On Wednesday, the justices seemed inclined to defend that rejection.

“At the end of the day, it’s pretty hard to argue that a tradition that’s been around a long, long time, since the founding … is inconsistent with the First Amendment,” said Justice Neil Gorsuch.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor appeared similarly dismissive of the case’s core argument.

“The question is: Is this an infringement on speech? And the answer is no,” she said. “He can sell as many shirts with this saying and the government’s not telling him he can’t use the phrase, he can’t sell it anywhere he wants. There’s no limitation on him selling it. So there’s no traditional infringement.”

Chief Justice John Roberts raised concerns about how it could potentially chill the speech of others if the court ruled in favor of the registration of Elster’s trademark.

“Presumably there’ll be a race for people to trademark, you know, ‘Trump Too This,’ ‘Trump Too That,’ whatever,” Justice Roberts said. “And then, particularly in an area of political expression, that really cuts off a lot of expression you might – other people might regard as important infringement on their First Amendment rights.”

The Biden Administration appealed a 2022 decision from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit which unanimously reversed the Patent and Trademark Office’s decision, which found that the trademark sought by Elster “is speech that is otherwise at the heart of the First Amendment.”

The question presented to the court asks “Whether the refusal to register a mark under Section 1052(c) violates the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment when the mark contains criticism of a government official or public figure.”

In Elster’s brief in response, he argued that “the statute makes it virtually impossible to register a mark that expresses an opinion about a public figure — including a political message (as here) that is critical of the president of the United States.”

Samuel Ernst, professor at Golden Gate University School of Law who filed an amicus brief in support of Elster, said the provision under which Elster’s trademark was denied effectively gives politicians a “heckler’s veto.”

“They can consent for registered trademarks that praise them and they can decline to register or consent to the registration of trademarks that criticize them,” he said in an interview prior to the arguments.

While the question before the court focuses on Elster’s free speech, experts are wary that no matter what the court decides, speech could ultimately be chilled.

“If Elster gets a registration for ‘Trump too small,’ it doesn’t guarantee he can stop other people from using this, even the same mark, but it gives him a statutory presumption of exclusive rights,” said Jonathan Moskin, counsel for the International Trademark Association, which filed an amicus brief on behalf of the Patent and Trademark Office, before the arguments. “So if I wanted to sell T-shirts with the name ‘Trump too big,’ or ‘Biden too small,’ he could potentially sue me and he would have more of a colorable claim by pointing to his registration, so giving him a registration might even inhibit free speech”

Lisa Ramsey, professor at the University of San Diego School of Law and a trademark law expert, shared Moskin’s view.

“There are free speech arguments both on [Elster’s] argument ‘I have a free speech right to register,’ but then there’s also a concern that if he or others get registration of political messages, then they can use that registration to chill speech,” she said in an interview before the arguments.

The case involves similar questions previously answered by the Supreme Court, but the precedents don’t apply cleanly to the current question.

In two recent cases — Matal v. Tam (2017) and Iancu v. Brunetti (2019) — the high court found that prohibiting the registration of trademarks based on their viewpoint violates the First Amendment.

In Tam, Simon Tam wished to trademark his band’s name, The Slants, but was denied because the mark disparaged members of a racial or ethnic group. In Brunetti, Erik Brunetti wished to trademark “FUCT” for his closing brand, but was denied because the mark was considered “immoral” or “scandalous” based on the pronunciation of the brand. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of both Tam and Brunetti.

But the provision of the Lanham Act which was used to deny Elster’s registration is “viewpoint neutral,” Ernst said.

He added that he believes Elster’s case is “as good a vehicle as any” for the high court to weigh the First Amendment implications to the provision of the Lanham Act.

“It really gets at these core First Amendment principles,” he said. “What the founders of the country were most concerned about with the First Amendment was the ability of powerful people to prevent citizens from criticizing them or criticizing their policies, especially politicians.”

Moskin, on the other hand, doesn’t think of “Trump too small” as a trademark dispute at all.

“I think it’s a distortion of trademark law to try to put this gloss of First Amendment rights on top of it,” he said. “I just don’t think it really applies.”

Rebecca Tushnet, a professor at Harvard Law School with expertise in trademark law, said the government is utilizing the same arguments the court has already rejected in both Tam and Brunetti.

The government is “basically saying ‘in your previous decisions, you just didn’t get it right,’” she said, “which is an interesting strategy, but in this case, it might work because the court’s grappling attempts so far were genuinely bad and they could sort of tell that they were genuinely bad.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with reporting on the oral arguments.

Nov. 1, 2023 — Vidal v. Elster oral arguments

Tags