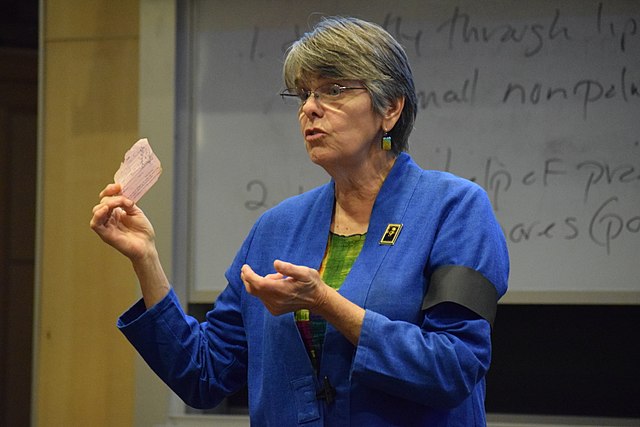

Catherine J. Ross is a professor at George Washington University Law School where she specializes in constitutional law (with particular emphasis on the First Amendment), family law, and legal and policy issues concerning children. Her book, Lessons in Censorship: How Schools and Courts Subvert Students’ First Amendment Rights (Harvard University Press, 2015) was named the Best Book on the First Amendment by Concurring Opinions’ First Amendment News (see FAW Excerpt), and won the Critics’ Choice Book Award from the American Education Studies Association. Professor Ross has been a co-author of Contemporary Family Law (Thomson/West) since the First Edition; the Fourth Edition was published in 2015.

Catherine J. Ross is a professor at George Washington University Law School where she specializes in constitutional law (with particular emphasis on the First Amendment), family law, and legal and policy issues concerning children. Her book, Lessons in Censorship: How Schools and Courts Subvert Students’ First Amendment Rights (Harvard University Press, 2015) was named the Best Book on the First Amendment by Concurring Opinions’ First Amendment News (see FAW Excerpt), and won the Critics’ Choice Book Award from the American Education Studies Association. Professor Ross has been a co-author of Contemporary Family Law (Thomson/West) since the First Edition; the Fourth Edition was published in 2015.

Emma Gonzalez speaks at the March for Our Lives protest in Washington, DC on March 24, 2018.

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas (MSD) students who became overnight activists and the thousands of other K-12 students they inspired are all modelling the vision of active citizenship that animates my book Lessons in Censorship: How Schools and Courts Subvert Students’ First Amendment Rights (Harvard University Press 2015). I argue there that what is at stake in teaching young people how to live liberty – particularly how to exercise their expressive rights – is nothing less than the future of our democracy. Like many, I am awed by the intelligence, articulateness and political savvy of the high school students who, without special preparation or any desire to lead a crusade, found themselves on the national stage after experiencing tragedy and proved themselves more than up to the task.

I write this on the weekend that hundreds of thousands of people — catalyzed by teenagers who survived the deadly massacre at MSD High School in Parkland Florida on February 14, 2018 – – at more than 800 locations around the world assembled to demand legal changes that would curtail rampant gun violence in the U.S.1 Those protesters were all exercising what even the White House — which rejects their substantive demands — recognized are their First Amendment rights.2 So too are the handful of counter-protesters who showed up at select locations.

The First Amendment fully protects such expressive assemblies and speeches outside of school hours and away from school campuses.

But what about the actions during the school day in schools across the country on March 14 to mourn those who perished at MSD, support the survivors, and demand action to prevent gun violence moving forward? Unfortunately, the answer to whether the First Amendment protected those protesters is less clear-cut. Bear in mind that First Amendment rights are strictly limited to those who attend public schools; independent schools are not bound by the First Amendment, which only applies to government entities.

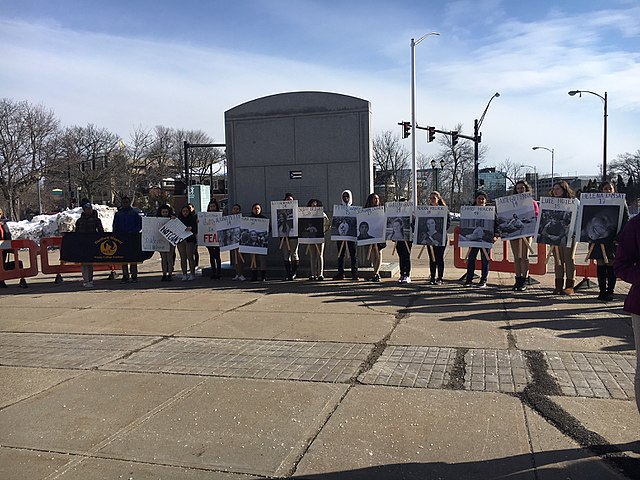

National Walkout Day March 14 2018

The March 14 demonstrations took a variety of forms. At some schools, students left class with permission to hold a silent vigil that lasted 17 minutes—one minute for each person who died at MSD. In others, students left without permission and returned in 17 minutes. At still others, the students were absent for the much of the school day: they left campus to demonstrate at Congress or the state legislature. The national press reported that while many schools accommodated students who desired to participate in a day of remembrance and action (“Principals and superintendents seemed disinclined to stop them”), others proposed alternative official activities (a moment of silence or assembly) while still others “seemed divided and even flummoxed about how to handle their emptying classrooms.”3

Special rules apply to the speech of K-12 students on campus during the school day. As a general matter, school officials may not silence or punish the expression of individual students unless the school can show that it reasonably anticipates the expression threatens to materially disrupt the school’s essential functioning (that is, education), as the U.S. Supreme Court held in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District (1969). Nor can schools ever punish students for their viewpoints on any issue. That much is clear. But the line of cases in which the Supreme Court set out the special rules that govern student speech in public schools is difficult to understand and to apply.

Mary Beth Tinker holding her original detention slip after she wore a black armband to school to protest the Vietnam War (with a replica on her left arm) during a speech at Textor Hall, Ithaca College, 19 September 2017.

The Supreme Court has never considered a case involving students who walked out of class to engage in a demonstration, but it has strongly hinted that leaving class is not a protected form of expression: In Tinker, the court upheld students’ right to wear a black armband as part of an antiwar protest, noting that the students had not engaged in any “group demonstration.” At a minimum, Tinker means that students who restricted their expression on March 14 to wearing orange – a statement encouraged by some organizers of National School Walkout including Women’s March Youth Empower – were engaging in precisely the kind of passive, silent and non-disruptive speech Tinker expressly protects. (One more wrinkle: unless a particular school can show it has a history of gang violence, including violence triggered by gang colors which might include orange).

Lower courts uniformly agree about walk-outs and demonstrations not being constitutionally protected in school, which makes sense. Students who are not in class are not learning; school is not functioning. Schools have the legal authority to punish students who absent themselves without permission, but that does not mean that officials need to exercise that authority when students are engaging in meaningful political activity, regardless of whether school officials agree with the students’ goals.

Many important lessons may be learned outside of class and curriculum. Civic engagement is one of them. One student I saw on March 14 in Washington D.C. carried a sign bearing the picture of a girl who died at MSD, along with this eloquent statement: “I missed a day of school because she missed the rest of her life.”

Similarly, schools that allowed students (or students who had parental permission) to leave class in order to participate in an orderly demonstration were seizing a teaching moment and helping students learn how to exercise their citizenship rights.

Similarly, schools that allowed students (or students who had parental permission) to leave class in order to participate in an orderly demonstration were seizing a teaching moment and helping students learn how to exercise their citizenship rights.

Sometimes, those who engage in civil disobedience must pay a price, whether in the world at large or in school. Needville High School in Needville, Texas used Facebook to warn students that there was no safety in numbers: “no matter if it is one, fifty, or five hundred students involved,” any student who protests on March 14 will be “suspended for 3 days and parent notes will not alleviate the discipline.”4 On the positive side, at least students who were thinking about protesting had advance notice of the penalty they would face.

With luck, the punishment will be proportionate to the offense. Schools that punished students who left class without permission did not violate students’ rights, though you, I or a given federal judge may have made a different calculation. Some colleges made that different calculation. They announced they in considering candidates for admission, they would not weigh penalties for participating in an unauthorized demonstration on March 14 sending a clear message about citizenship and responsibility.

Some schools went further than disciplining students who missed class on March 14: they punished students for what they said while demonstrating.

One incident that received a lot of national attention requires precise legal analysis. Noah Christiansen, a student at McQueen High School in Reno, Nevada, was suspended for two days and barred from assuming the position as class secretary to which his peers had just elected him after he cursed at a congressional staffer during a telephone call in which he was lobbying for gun control. The protesters at McQueen had left class, and were marked “tardy” for the class that followed. They decided to use the walkout on March 14 to call their congressional representatives.

During a phone call to his Congressman’s office, Christiansen told a staff member that lawmakers needed to “’get off their f-ing asses and do something about gun control.’”5 After the staffer complained to McQueen’s principal, the school punished Christiansen for violating its rules about “defiance/disrespect/insubordination,” telling Christiansen (who apparently had an unblemished disciplinary record up to that point) that his behavior was “very embarrassing” for the school. Institutional embarrassment — while frequently the actual motivation for censoring student speech — is not a constitutionally sufficient justification for suppressing protected expression. Christiansen admitted that he had shown poor judgment, and probably should have chosen different language, but asserts, “’if I do want to use words, and use them over and over again, it’s my right to do so.”6

Is he right? Many schools forbid and punish cursing on campus. Some courts have upheld such penalties as perhaps unwise but beyond the purview of the judiciary. Outside of school, the Constitution allows speakers to choose the manner of expression they find most effective: “it is often said that one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric.” Cohen v. California (1971). Many judges have accepted without questioning that Cohen’s jacket (bearing the f-word) may be protected in a courthouse but has no place in a school. My scholarship, however, casts doubt on that abrogation of students’ rights to choose the manner in which they express their ideas, a right that adults have long possessed.

The Constitution protects cursing, even in school, unless in context it has sexual connotations, in which case the school has almost unlimited discretion to punish it under yet another school speech case. Bethel v. Fraser (1986). So, the first question is whether the f-word is always sexual. Arguably, it was not used that way in Christiansen’s conversation.

If it fell within the school’s discretion to punish Christiansen’s choice of language, it would matter whether he spoke during the school day from the school campus, or whether, as some observers claim and as Christiansen himself reportedly views it, he “had not made the phone call from class, or a school event; he was already marked tardy.”7 Does that mean that his expression took place outside the school day and from off-campus? If so, different rules should apply — the rules that apply in the world at large, not the special rules that offer students in public schools a diminished form of First Amendment protection. The outer parameters of where speech takes place in school and out of school can be murky as the Supreme Court noted in Frederick v. Morse (2007). In that case, the Court held that an 18-year-old senior who had not shown up at school that day but joined his friends for an school-sanctioned event across the street from the school under faculty supervision was in school for purposes of discipline resulting from his display of a banner that proclaimed “Bong Hits 4 Jesus.”

To figure out where Christiansen’s speech took place from a constitutional perspective, we’d need to know a lot more details, including: where was Christiansen located – outside but still on the campus or across the street on a public sidewalk? Were there any teachers watching the protesters to ensure order and safety? Had there been any public indications that the school was tacitly allowing the protest?

One thing, however, is crystal clear. If Christiansen was punished for his political views, in an act of “retribution,” as the ACLU asserted, the penalty violated his First Amendment rights and would cast an impermissible chill over other students who “’are considering engaging in the political process,’” as the ACLU put it in a letter to school district officials.8

That is exactly the wrong lesson to send to America’s invigorated students.

The young people “marching for our lives” today are following our best patriotic traditions.

As we approach the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. these outspoken students channel their African-American peers who jumped out of windows and trampled the fence surrounding their segregated Birmingham high school to demand civil rights, in an action that captured the nation’s heart and became the Children’s Crusade;9 the African-American students in Mississippi whose activism for voting rights following Freedom Summer gave rise to the court cases that provided the model for the test the Supreme Court applied to student speech in Tinker;10 and the students in some 10,000 high schools across the nation who in 1969 walked out to protest the war in Viet Nam, reportedly causing President Nixon to reassess the political costs of escalating military action.11

___

[1] Ashley Collins,’Welcome to the revolution’: Parkland students lead emotional March for Our Lives rally, USA Today, March 24, 2018.

[2] Avery Arapol, White House applauds gun violence protesters for ‘exercising their First Amendment rights, The Hill, March 24, 2018.

[3] Vivian Yee & Alan Blinder, National School Walkout: Thousands Protest Against Gun Violence Across the U.S., New York Times, March 14, 2018.

[4] Sarah Gray, Thousands of Students Walked Out of School Today in Nationwide Protests. Here’s Why, Time, March 13, 2018.

[5] Avi Seik, A student called his congressman to ask for gun control—and was suspended for cursing, Washington Post, March 20, 2018.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Catherine J. Ross, Lessons in Censorship, pp. 151-152.

[10] Catherine J. Ross, Lessons in Censorship, pp. 152-154.

[11] James Hohman with Breanne Deppisch and Janie Greer, The Daily 202: How the marches for gun control are like the protests against Vietnam, Washington Post, March 26, 2018.

Tags