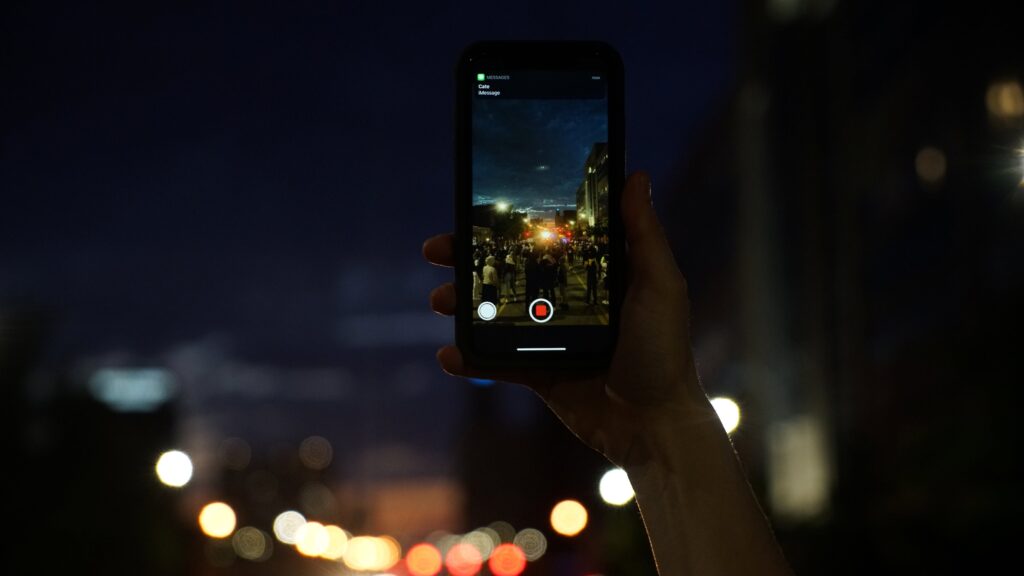

Editor’s note: The story is updated with the news that on July 11, 2022, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, based in Denver, joined six federal courts in affirming there’s a First Amendment right to film the police performing their duties in public.

Arizona Gov. Douglas Ducey signed into law a bill that would make it illegal to photograph or record a police officer in public from a distance of eight feet without the officer’s permission.

Controversial House Bill 2319 says if an individual is asked by the police to quit filming but continues to do so would face a Class 3 misdemeanor and up to 30 days in jail.

See our teacher guide on the right to record police or the more concise citizen’s guide to recording the police.

The bill was sponsored by Republican state Rep. John Kavanagh, a former police officer, who contends that the measure is necessary to protect the public’s and officers’ safety.

But critics in the media and First Amendment advocacy groups are vocal, calling the legislation unconstitutional, and asserting this law would give police the power to decide who can report on their conduct in public. The Phoenix police department is currently under investigation by the Justice Department for its use of force against protesters and homeless people, and in recent years, has posted record numbers of police shootings, according to AZ Central.

While the U.S. Supreme Court has not yet weighed in on the right to record police, the U.S. Court of Appeals in the First, Third, Fifth, Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh have all ruled that the right to record police in public places is protected by the First Amendment. On July 11, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, based in Denver, joined the previous six federal courts in affirming there’s a First Amendment right to film the police performing their duties in public.

In the Ninth Circuit—which includes Arizona—in Fordyce v. City of Seattle (1995), the court protected the right to document activities that take place in public spaces. In 1990, Jerry Edmons Fordyce sued eight police officers who arrested him for filming a public demonstration in downtown Seattle. At one point, Fordyce recorded a bystander and her two minor nephews who were standing on a public sidewalk. The woman asked Fordyce to stop filming them, and when he refused and continued to film, the woman complained to a police officer. The officer told Fordyce that a state statute made it a misdemeanor to record a private conversation without consent, but Fordyce continued to film, saying they were all on public property.

The Ninth Circuit ruled that the Washington state statute “does not make criminal the recording of conversations held in a public street, in voices audible to passersby, by the use of a readily apparent device.”

The Arizona law goes into effect in September. In a letter sent to the governor days before he signed the bill, Mickey Osterreicher, general counsel of the National Press Photographers Association, (NPPA), wrote, “The bill violates the free speech and press clauses of the First Amendment and runs counter to the ‘clearly established right to photograph and record police officers performing their official duties in a public place, cited by all the odd-numbered U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal, including the Ninth Circuit.’

“All of these courts have held that police officers who are performing their duties in public have no reasonable expectation of privacy when it comes to being recorded,” Osterreicher wrote. NPPA’s letter to the governor was supported by more than 20 organizations, including First Amendment Coalition and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.

First Amendment Watch founding editor Stephen Solomon commented in a Washington Post story that the law is a violation of the First Amendment.

AZ MIRROR Washington Post NPPA HB2319

Tags